10 Chapter 10: Primer on Indigenous Peoples’ Histories Across Canada

Kyle Napier

Introduction

Here’s a question: why should Indigenous Peoples be given any special consideration in the media? What makes them so special? Go ahead — think of an answer. I’ll wait.

How about this — think about where you are right now. Do you know the histories of the Indigenous Peoples of these lands? Are you prepared to tell the story of the place underneath your feet? What about the recent and complex histories of Indigenous Peoples? For millennia, these lands were the domain of Indigenous Peoples — and now, Indigenous Peoples only comprise 3.2% of Calgary’s population (Alberta Regional Dashboard, 2021).

You might ask: Why is that? When did this happen? What does this have to do with media? Well, you’ll want to sit down for this one, young media-maker. There’s a long history of those content creators before you who have asked the same question, and the more informed they were, the better prepared they were, and the better media-makers they grew to be.

This continent’s history begins far before North America as we know it today. Without Indigenous Peoples on this continent, it’s unlikely the first explorers would have survived their first few winters. Without the help of Indigenous Peoples, everything would have been drastically different — from the spans of industrial revolutions, to the outcomes of war, to the foundations of democracy, and even your presence on this continent.

This chapter takes you on a journey through thousands of years of Indigenous histories, condensed into several short pages. You will have a broader understanding of various distinct Indigenous groups across this continent and the roles of media in colonization. Along with the next two following modules, this module responds to the Truth and Reconciliation – Call to Action #86, which states: We call upon Canadian journalism programs and media schools to require education for all students on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations.

As you read this chapter and the next, consider the timeline of mediated representations of Indigenous Peoples. At the time of publication, what was the prevailing bias of the nation-states? How have media upheld these biases? How has the media informed your perspective on Indigenous Peoples? The last chapter for this course will then ask you to consider how your response to these questions might inform your ongoing media practice.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain the long-standing histories of Indigenous Peoples around the world and on this continent.

- Describe the significance of residential schools, UNDRIP in Canada, Treaties, Aboriginal Rights, Indigenous Law, and Indigenous-Crown relations.

- Summarize the relationships Indigenous communities have with their lands and peoples across Treaty 7.

- Discuss the foundational historical, legal, and social issues that shape media content related to Indigenous Peoples and their communities.

What does Indigenous mean? And who is Indigenous?

To think critically about media histories of Indigenous Peoples, it’s essential to be aware of the distinct histories of the many, many distinct Indigenous Peoples globally, continentally, and just around the corner from you at your university. Indigenous Peoples are those groups of humans with long-standing histories in a specific place, and whose existence in those lands long predates colonization.

Even the term “indigenous” has its history. The term “indigenous Peoples” first emerged in the context of social reforms by the International Labour Organization during the 1950s, before being adopted by Indigenous NGOs and eventually becoming a standard element in human rights frameworks and international organizational discourse.

Not too long ago, Indigenous Peoples were Aboriginal, and before that, Indians, Half-Breeds, and Eskimos. Please note that each of those terms is now considered offensive, but at one time, they represent the prevailing verbiage. In this context, Indigenous Peoples are those Peoples who have lived on their respective lands before the imposition of an outside nation-state government, and there are Indigenous Peoples on every continent. For thousands of years, distinct Indigenous Peoples worldwide have maintained a distinct connection with their lands, languages, and laws (Whiskeyjack and Napier, 2020).

Consider the world’s population: more than eight billion people live in 200 nation-states worldwide. Of these, nearly 370 million are Indigenous Peoples, residing in approximately 70 nation-states and speaking more than 4,000 distinct languages (International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, 2019; United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues [UNPFII], 2020). Each language group has its worldviews, knowledge systems, governance structures, protocols, and relationalities (Wilson, 2008).

In Canada, the term Indigenous Peoples refers to three major groups — First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. There are over 630 distinct First Nations across Canada; numerous Métis nations, communities, and peoples; and Inuit residing beyond the four regions of Inuit Nunangat, which means “the place where Inuit live,” (Statistics Canada, 2019; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2021).

The Assembly of First Nations, originating from the National Indian Brotherhood formed in the 1970s, claims to represent the collective interests of all First Nations (Assembly of First Nations, 2023). The Métis National Council currently represents the Otipimisewak Métis Government (OMG) and the Métis Nation of Ontario (Métis National Council, 2023). Inuit are represented by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national Inuit advocacy organization (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2021).

Indigenous Peoples’ long-standing histories and the recent histories of colonization

Indigenous Peoples’ histories begin with their distinct Creation stories and have been passed down through their unique communities ever since. Many Indigenous communities in Canada have preserved oral traditions that recall events from before the last glacial period, roughly 10,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence, such as findings from the Bluefish Caves in Yukon, indicates human presence in North America dating back at least 24,000 years (Bourgeon, Burke, & Higham, 2017), and fossil records show human ancestors from more than 200,000 years (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, n.d.). Even by the most conservative estimates, Indigenous Peoples have maintained millennia-long connections to these lands, along with the worldviews, knowledge systems, and protocols that arise from their enduring relationships with the environment.

It may be challenging to know what life was truly like for Indigenous Peoples before contact. Contact and trade with the early colonizers contributed to the vast spread of tuberculosis, measles, smallpox, influenza, malaria, and scarlet fever, brought to the continent by Europeans. It’s commonly cited that exposure to these European diseases would kill more than 90% of Indigenous Peoples in North and South America, or roughly 55 million Indigenous Peoples (Koch et al., 2019).

What is now taught in the history books about Indigenous Peoples is what has blossomed through the cracks of colonial pavement. Besides oral histories of Indigenous Peoples, most of what is known about Indigenous Peoples is derived from law and policy, anthropological accounts, and media. The biases of their fields often taint early anthropological records. Early anthropologists would compare brain capacities of different groups they categorized into “races” by filling the skulls of peoples — in this case, those of European male adults and Indigenous children — with millet, to determine whose skull carried more brain capacity (Smith, 1999, p. 1). Law and policy are written by the colonizing government, carrying the era’s biases and language. And of course, media sustains the worldviews of the peoples from which it emerges.

Indigenous communities, lands, and peoples in Alberta and across Treaty 7

Indigenous presence in Alberta is represented by approximately 140 distinct First Nations reserves distributed across three treaty areas: Treaty 6, Treaty 7, and Treaty 8. Treaty 6 covers central Alberta, including Red Deer and extends into Saskatchewan, while Treaty 7 encompasses southern Alberta, including Calgary, Banff, and Lethbridge. Treaty 8 includes northern Alberta communities such as Jasper and Fort McMurray and extends into British Columbia and the Northwest Territories (Indigenous Services Canada, n.d.; Government of Alberta, 2023). Alberta also has eight Métis Settlements, governed collectively by the Métis Settlements General Council, which administers the land divided into five regions and further into districts (Métis Settlements General Council, n.d.). Inuit in Alberta have a more recent presence with growing communities in urban centers such as Calgary and Edmonton. Some Inuit in these cities may identify informally with terms like “Calgarymuit” or “Edmontonmuit” (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2021). Although Indigenous Peoples comprise approximately 6.8% of Alberta’s population, only about 1% of land within Alberta is designated as reserve or settlement lands (Statistics Canada, 2022; Government of Alberta, 2023).

Treaty 7 includes many distinct Indigenous communities, lands, and peoples, each with unique histories. It is often associated with the Blackfoot Confederacy, which consists of the Siksiká, Káínaa (Blood), and Piikáni (Peigan) Nations, collectively known as the Niitsitapi or Blackfoot Peoples. However, Treaty 7 also includes other nations such as the Tsúùtʾínà (Sarcee) and Îyârhe Nakoda (Stoney), who are not part of the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Before we even get to the media from Indigenous Peoples, we need to understand the context of the Indigenous Peoples of the lands where you are. If you are reading this as a student at Mount Royal University, you are likely already aware that you are on Treaty 7 territory. You should know that this land has only recently been referred to as Treaty 7.

This is a binding treaty between the Crown and the Indigenous Peoples of Treaty 7. Treaty 7 was signed in 1877, a decade after the formation of Canada. It is a contract bound in signatures and pipe smoke, conducted between the Crown (or the royalty of England, as represented by Canada) and the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy) — which includes the Siksika, Piikani, and Kainai — as well as the other Indigenous Nations of Treaty 7, which include the Îyârhe Nakoda (Stoney Nakoda) and Tsúùtʾínà.

Now, hold up — let’s revisit that last paragraph and the lands you are on right now.

Do you know how to pronounce the names you just read, of those Indigenous Peoples across Treaty 7? How decolonial can your media really be if you are mispronouncing the names of the people you are creating media about? Alright, so let’s practise learning how to pronounce the names of the Indigenous Peoples whose lands you are on.

Let’s break this down syllable by syllable. I’ll provide the closest English word equivalents to help with your pronunciation:

Niitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy) —

Neat-sit-a-pee

Siksika —

Sick-sick-ah

Piikani —

Pick-ah-knee

Kainai —

Gaih-nye

Îyârhe Nakoda (Stoney Nakoda) —

Ee-yarr-hey Na-ko-da

Tsúùtʾínà —

Soot-in-a

(You should be able to say Tsúùtʾínà without moving your lips.)

There — now that you have practised pronouncing the names of the Peoples whose lands you live upon, we can talk more deeply about their ancestral media and communications, and their critical adoption of more contemporary media and communications.

After Treaty 7 was signed in 1877, the newly formed North West Mounted Police, the predecessor to today’s Royal Canadian Mounted Police, were sent to enforce colonial control in the area. Part of their task was to remove Indigenous Peoples from their traditional lands to create Banff National Park in 1885, which became the first national park in Canada. The Indian Agent system, formalized in the 1870s, further restricted First Nations’ movement by enforcing the pass system, which required Indigenous people to have permission to leave their reserves (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRC], 2015).

Despite these colonial actions, Euro-Western histories have often failed to recognize Indigenous contributions to contemporary knowledge and society. In 1938, Abraham Maslow’s had visited with Blackfoot across Alberta — learning from them, and drawing their understandings of well-being to include what you may know now as Mazlow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” (Alards‑Tomalin & PSYC 303 Students, n.d.)

First Contact with the Europeans

Let me tell you a long story in a few short pages. This story covers more than 500 years of colonization; however, it is essential to remember that Indigenous histories on this continent span thousands of years, most of which cannot be described in brief mentions within history books (Smith, 1999; Wilson, 2008). Colonization is an inherently global process that began several hundred years ago. Scholarship on decolonization draws from diverse regions across Asia, Africa, Europe, the Americas, Australia, and the Arctic. Every individual is impacted by colonization today, and extensive decolonial literatures are emerging worldwide (United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2020). In the Canadian context, colonization refers to the ongoing exercise of power and force to seize land and resources from Indigenous peoples, maintained through colonial structures. Readers are encouraged to reflect on how colonization affects them personally as they engage with this chapter.

Before the more recent 500 years of colonization, there was the systematic dehumanization of others to justify using force and seizure of resources. Central to this was papal doctrine supporting colonization. Although the exact origins are unclear, the concept of “Terra Nullius” declared that non-Christians were not considered people; thus, their lands were deemed unoccupied and available for colonization (Koch et al., 2019). This doctrine laid the foundation for international colonization, followed by the Doctrines of Discovery (Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2017).

The initiation of colonization in the Americas, as we understand it today, began with Christopher Columbus. Although Columbus never set foot on what is now known as North America, the first known contact by Europeans was by Leif Eriksson around the year 1000 CE; however, attempts at colonization at that time were abandoned as impractical (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, n.d.). Five centuries later, Columbus set sail from the Crown of Castile with three ships equipped with guns, maps, paper, and a compass.

Columbus landed on an island he called San Salvador, now widely believed to be in the Bahamas, in 1492. There, he encountered the Taíno people, an Arawakan-speaking group indigenous to the Caribbean. While initially considering ways to exploit the peaceful nature of the Taíno, Columbus and his men were armed and would soon engage in acts of violence and enslavement. Columbus forcibly took Indigenous individuals back to Castile (Spain), where some were displayed or enslaved. Over time, he implemented systems of forced labour, most notably the encomienda system beginning in 1502, that led to exploitation and death for many Indigenous peoples (Lacas, 1952).

Following Columbus’s voyages were the papal Doctrines of Discovery, a series of decrees including Dum Diversas (1452), Romanus Pontifex (1455), and Inter Caetera (1493). These documents authorized the enslavement, subjugation, and colonization of lands inhabited by non-Christian “saracens”, “pagans”, and “any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ” (Canadian Council of Catholic Bishops, 2017). The Age of Discovery thus proceeded without the consent of Indigenous people.

Of the Taíno people before European contact, scholarly estimates vary widely and remain heavily debated, with some suggesting populations in the hundreds of thousands to over a million for the Caribbean region. Whatever the initial numbers, the population had been dramatically reduced by 1496, following Columbus’s third voyage (Henige, 1978). The enslavement of human beings is inherently unjust. Columbus was eventually imprisoned in San Domingo due to his mismanagement and mistreatment of Indigenous peoples; however, as the Taíno and Arawak were not considered “people” under Christian doctrine, Columbus appealed to Pope Alexander VI and was subsequently released to undertake further voyages (Smith, 1999).

Colonization is predicated on the theft and misappropriation of Indigenous knowledge (Okediji, 2018) and the subjugation of Indigenous peoples. The mass depopulation, dehumanization, and violent seizure of land during this period foreshadowed the centuries of colonization in what is now Canada and set a precedent for global state-sponsored colonization (Wilson, 2008). Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1986) writes: “The bullet was the means of physical subjugation. Language was the means of the spiritual subjugation” (p. 9). This was true of global colonization, which would follow.

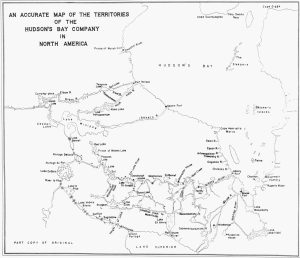

Early colonization, economics, and the Hudson Bay Company — 1500s-mid-1700s

As I write this chapter (Spring 2025), the now-retired outlet The Bay is auctioning off its merchandise and materials, closing its doors for good. They once stood as an empire, owning more than a third of what is now referred to as Canada for over two hundred years. It all began in 1667, when early fur traders first met the nêhiyawak (Cree peoples). The then King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland issued a Royal Charter, granting the Hudson’s Bay Company domain over those lands between 1670 and 1870 (Gismondi, 2020). The territory was named Rupert’s Land after Prince Rupert, who died in 1682.

Capitalism as we know it today hadn’t yet come into force. The economic pursuits of the colonizing governments at the time were to support their home countries—this was done through mercantilism, or the sending back of financial goods and proceeds to colonizing nation-states. The fur trade, most prominent between the 1600s and 1800s, contributed to a vast transfer of wealth to Europe and a mass depopulation of fur-bearing species in North America. Of course, the colonizers seemingly hadn’t thought to ask the Indigenous Peoples if they would like any say over their dominion.

Indian Affairs: The Indian Act, Treaties, and the encroachment of Canada (1755 — 1876)

As you know by now, the long histories of European-Indigenous relations and rights are complex. What we now know as Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) has its roots in a series of colonial and federal institutions. In 1755, Britain established the British Indian Department to manage relations with Indigenous nations, especially during wartime alliances. After the American Revolution, the Department was divided, with the U.S. forming the Bureau of Indian Affairs (now within the U.S. Department of the Interior) and the British-controlled section eventually evolving into the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs in the 19th century (Leslie, 2002).

Indian Agents, who served as the Crown’s local representatives enforcing colonial policy and administering the Indian Act after 1876, operated in what is now Canada from the early 1800s until the 1960s, although their powers declined in the mid-20th century. Their role was central to implementing the reserve system, pass system, and residential schools (Milloy, 1999; Leslie, 2002).

Britain’s Royal Proclamation of 1763 required all colonizing governments to sign treaties with distinct groups of Indigenous Peoples before occupying land. A critical caveat: only the British Crown could legally sign those treaties (Indigenous Services Canada, n.d.). The United States famously rejected this authority, beginning with the Boston Tea Party of 1773, during which American patriots disguised themselves as Mohawk warriors—a deeply ironic act of appropriation. The U.S. would declare independence by 1776.

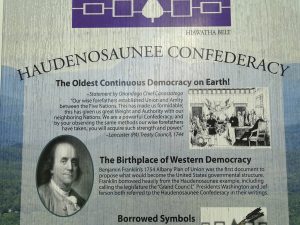

Indigenous Peoples are experts in intergovernmental diplomacy, having maintained sophisticated systems of governance and treaty-making with other nations, ecosystems, and species for thousands of years. By 1789, the United States ratified its Constitution, and some U.S. constitutional scholars have acknowledged the influence of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy on its formation, particularly their principles of federalism and consensus governance (Lyons et al., 1992). The Haudenosaunee also participated in what is often recognized as the first recorded treaty between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples in what is now Canada: the Two Row Wampum Treaty of 1613, an agreement between the Haudenosaunee and Dutch settlers. The treaty was symbolized through a wampum belt and recorded in Dutch writings and oral traditions, representing a commitment to mutual respect and non-interference (Duhamel, 2018).

Colonial expansion in the 1700s led to numerous conflicts among European empires vying for control in North America. France allied with various Indigenous Nations, such as the Mi’kmaq and Abenaki, to bolster their position against the British. Meanwhile, Britain negotiated a series of Peace and Friendship Treaties primarily in the Maritime provinces during the 1700s and early 1800s. These treaties did not surrender Indigenous land or sovereignty but aimed to establish peaceful coexistence and alliances between the Crown and Indigenous Nations (Fisher, 1992; Wicken, 2011).

The Industrial Revolutions intensified settler demands for land and resources. The first Industrial Revolution began in the mid-1700s with the steam engine and textile manufacturing. The second emerged in the mid-to-late 1800s with the combustion engine and electricity (Schwab, 2017). The third, starting in the 1960s, saw the development of the microprocessor, leading to computing. We are amidst a fourth Industrial Revolution, marked by digital technologies, artificial intelligence, and blockchain (Schwab, 2017). Each technological leap brought increased pressure to displace Indigenous Peoples and exploit their lands (Estes, 2019).

In America, pressures on Indigenous Peoples increased significantly after the War of 1812, as British support for Indigenous sovereignty diminished and Indigenous Nations were increasingly viewed as obstacles to American expansionist goals (Perdue & Green, 2005). Between 1830 and 1850, the U.S. government forcibly removed tens of thousands of Indigenous peoples, primarily from the southeastern United States, through policies such as the Indian Removal Act of 1830. This resulted in the Trail of Tears, a series of forced relocations to designated Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, during which thousands of Indigenous people died due to harsh conditions, disease, and starvation (Ehle, 1988).

Canada would form in 1867 (Historica Canada, 2017). In Canada, settler governance evolved through legislation aimed at assimilating Indigenous Peoples. In 1869, the Canadian government acquired Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, expanding its territorial control. Prior to Confederation, the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857 and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act of 1869 laid the groundwork for the Indian Act of 1876. The Gradual Civilization Act sought to “voluntarily” assimilate Indigenous individuals into settler society by offering enfranchisement, which required Indigenous men to renounce their legal Indian status in exchange for land and citizenship rights. However, this policy saw minimal uptake; notably, only one individual, Elias Hill, a Mohawk man, successfully enfranchised under the Act. Hill enrolled in 1859 and later sought compensation for promised land and financial losses in 1879 (Leslie, 1978).

The Gradual Enfranchisement Act of 1869, passed by the first Canadian Parliament, introduced the concept of Status Indians and imposed a patriarchal system of band governance. It also disenfranchised Indigenous women, particularly those who married non-status men, stripping them and their children of legal Indian status. These legislative measures collectively contributed to the assimilationist policies that culminated in the Indian Act of 1876 (Miller, 2000; Leslie, 1978).

The timing would coincide with the early stages of a new wave of global colonization, most notably the “Scramble for Africa”—the aggressive partition and colonization of African territories by European powers including France, Britain, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Although exploratory and commercial activities had begun earlier, the formal division of Africa intensified after the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, which established the rules for European claims and marked a turning point in imperial expansion across the continent (Pakenham, 1991).

Residential schools: Beginnings, Abuses, and Justice, to RCAP, the IRSSA, and the TRC

[Trigger Warning: This section contains mature and graphic content related to abuses against children.]

Perhaps the most egregious and grievous of offences maintained by Canada were the tragedies upheld by the state across Indian boarding schools, residential schools, and day school systems. Residential schools were a deliberate attempt to subjugate Indigenous languages, cultures, knowledge, and Peoples (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRC], 2015). Before the late 1800s, most attempts at religious conversion by church or state had failed. Early missionary efforts began in 1610 but were largely unsuccessful (Milloy, 1999). The first industrial day school opened in 1828 (TRC, 2015). Missionary efforts to convert Inuit communities increased by the mid-1800s, though Inuvialuit author Harold Cardinal observed that his community looked “distrustfully on all this” (Cardinal, 1999).

John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister and often described as Canada’s “architect of residential schools,” was influenced by the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, founded in 1879 by Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt. In 1892, Pratt infamously declared: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” revealing the core assimilationist logic of these institutions (Pratt, 1973).

Abuse in residential schools targeted children’s bodies, minds, hearts, and spirits. Indigenous children had their hair cut, traditional clothing taken, and were punished, sometimes violently, for speaking their languages. Nutritional experiments were conducted in which children were intentionally starved to observe the effects of vitamin and protein deficiencies (Mosby, 2013). Sexual abuse, while not experienced by all, was widespread. It was common for priests and nuns to remove children from their beds at night for sexual assault (TRC, 2015).

Influential designers and supporters of the residential school system, such as Nicholas Flood Davin and Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, openly advocated for the complete assimilation of Indigenous Peoples. Both Davin’s 1879 Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds and Scott’s speeches insisted that assimilation was a solution to the so-called “Indian problem” (Milloy, 1999). In 1883, the federal government partnered with churches to deliver state-sponsored education that erased Indigenous identities. The Indian Act made attendance mandatory in 1894 and again in 1920 for children legally defined as “Indians” (TRC, 2015).

In 1907, Dr. Peter Bryce, Chief Medical Officer for Indian Affairs, exposed appalling health conditions in residential schools. When the government refused to publish his findings, he self-published The Story of a National Crime in 1922. He reported that mortality rates in some schools exceeded 50%, writing, “I believe the conditions are being deliberately created in our residential schools to spread infectious diseases” (Bryce, 1922, p. 20).

Abuses, neglect, mistreatment, malfeasance, and childhood death would be well-evidenced in Canada’s largest class action lawsuit, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), which concluded in 2006. Among other remediative measures, one mandate of the IRSSA was Schedule “N,” which called for the formation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, 2006). Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, inspired by the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa, was created to honour the voices and truths of the survivors and warriors who experienced the residential school system (TRC, 2015).

The last federally operated residential schools—Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet and Cowessess Indian Residential School in Marieval, Saskatchewan—closed in 1997 (TRC, 2015).

Child Welfare and Forced Sterilization of Indigenous Women in Alberta

There are currently more Indigenous children in child welfare services than were Indigenous children attending residential schools at the height of residential schooling in the 1920s. According to Statistics Canada (2022), Indigenous children made up 7.7% of the child population but accounted for over 50% of children in foster care. At the height of residential schooling in 1921, approximately 20,000 Indigenous children were enrolled in these institutions (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). Today, tens of thousands are in the child welfare system — more than at any point during the residential school era (Blackstock, 2024).

Canada’s child welfare system is fragmented, with over 300 agencies across provinces and territories (Statistics Canada, 2024). This fragmentation contributes to challenges in maintaining precise, comprehensive national data on Indigenous children in care.

Policy changes in the 1950s, particularly the 1951 amendments to the Indian Act and subsequent provincial child welfare policies, significantly increased the removal of Indigenous children from their families (Blackstock, 2024; Sinclair, 2007). Poverty and lack of economic opportunities on reserves are often cited as underlying causes for child removals, reflecting systemic social and economic inequities (Blackstock, 2024).

In Alberta, the Sexual Sterilization Act of 1928 allowed for the forced sterilization of over 2800 individuals deemed “unfit” by eugenicist doctors (Klassen, 2000). The act was repealed in 1972, but reports and investigations have revealed more than 100 cases of coerced and forced sterilization of Indigenous women for decades after. In 1999, Alberta’s then-Premier formally apologized for the abuses under the Act. In 2023–2024, the Canadian Senate debated bills to outlaw forced and coerced sterilizations nationwide explicitly. Still, as of 2024, no federal legislation has been passed to comprehensively ban the practice (Senate of Canada, 2024).

Indigenous Peoples across Canada, the United Nations, and UNDRIP

The United States, founded on principles of confederation, was influenced by the political system of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (United States Senate, 1987).

However, Indigenous Peoples — and the languages the government and church fought to suppress — were later weaponized by Canada and the United States during both World Wars. Soldiers who spoke Indigenous languages were recruited as “Code Talkers” to send secret military communications that enemy forces could not decipher (Kahn, 2009).

The League of Nations, which was established in 1920 during the Paris Peace Conference following World War I, was the first international body aimed at promoting peace and human rights. However, Indigenous voices were excluded from participation. For example, Deskaheh, a Haudenosaunee Chief, was barred from addressing the League in 1923 (Johansen & Mann, 2000). Similarly, in 1925, Maori representatives from Aotearoa (New Zealand) were also denied participation (McHugh, 2004).

World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust led to increased scrutiny of nation-states’ treatment of those residing within its’ borders (Power, 2002). The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the United Nations in 1948 in response to these atrocities (United Nations, 1948). India achieved independence from Britain in 1947, following prolonged decolonization efforts. This sparked waves of decolonization across Africa through the 1950s and subsequent decades, with African nations each navigating decolonization in their own distinct ways (Cooper, 2002; Betts, 1998).

In 1982, the United Nations established the Working Group on Indigenous Populations to address Indigenous Peoples’ rights and issues (United Nations, n.d.). While Indigenous Nations cannot become UN member states, members can participate as observers in meetings concerning Indigenous affairs (United Nations, n.d.). By 1985, this Working Group had begun drafting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

The International Labour Organization adopted Convention 169 (ILO 169) in 1989, a binding international treaty affirming Indigenous and tribal peoples’ rights and explicitly prohibiting nation-state assimilationist policies (International Labour Organization, 1989).

UNDRIP was passed by the United Nations General Assembly in 2007, with four nations opposing it: Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand (United Nations, 2007). These countries had significant colonial histories with Indigenous populations and sovereignty and land rights concerns.

Eventually, all four nations withdrew their opposition. However, each has a complicated history regarding the implementation of UNDRIP. Canada’s adoption has been critiqued for a lack of good-faith negotiation and meaningful consultation with Indigenous Peoples (Diabo, 2021). The Canadian government’s approach assumes that federal and provincial laws supersede Indigenous laws, contradicting UNDRIP’s principles of Indigenous sovereignty. Furthermore, Indigenous Peoples were largely excluded from the federal government’s adoption and ratification process (Government of Canada, 2021).

The big difference between Indigenous Law and Aboriginal Law

Now, hold up — let’s back up a few centuries. Before Canada, before UNDRIP, before the Indian Act, before the Royal Proclamation of 1763, before the Doctrines of Discovery, and even before Terra Nullius, there were the laws and sacred protocols which have governed Indigenous nations and societies for thousands of years, and continue to today in their own respective ways.

These laws — which predate colonization by thousands upon thousands of years — are Indigenous laws. These laws are embedded in Indigenous languages, which themselves are deeply connected to the land (Simpson, 2014; Corntassel, 2008). Of course, it is the land which Canada attempted to seize from Indigenous Peoples, and their languages which Canada attempted to eradicate (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRC], 2015). However, Indigenous laws still exist, as do Indigenous languages, and the lands of which Indigenous Peoples are the ancestral stewards.

This, of course, doesn’t sit well with Canada. However, Indigenous laws and connections to land have been consistently affirmed in Canada’s Supreme Court. Cases such as R v. Sparrow (1990), R v. Daniels (2016), Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014), Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada (2018), Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997), and R v. Van der Peet (1996) each affirm Indigenous rights, laws, and ancestral title to Indigenous lands (Borrows, 2016; McNeil, 2018).

This legal recognition has shifted the focus from historical treaties to modern comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements. Note that both modern comprehensive land claims and self-government agreements are negotiated within the language and legal frameworks of the colonizing government — in this case, Canada (Alfred, 2005; Coulthard, 2014). Modern land claims tend to affirm colonial-style rights, title, and jurisdiction over ecological management, surface, and subsurface lands. Self-government has been critiqued as adopting Canadian electoral political models, which often contrast with the ancestral hereditary chiefs, matriarchal systems, and hundreds of distinct governance models Indigenous nations have used since time immemorial (Alfred, 2005; Coulthard, 2014).

In sum, Indigenous law refers to the pre-contact laws and protocols maintained by Indigenous Peoples since time immemorial. Aboriginal law, conversely, refers to the body of law imposed by Euro-Canadian legal systems onto Indigenous Peoples within the context of Canada (Borrows, 2016).

Okay, so, I think I understand First Nations law now — do Métis have their own laws?

Actually, yes! The Métis are a distinct group of Indigenous Peoples whose history spans various points of contact between Europeans — usually French, English, or Scottish — and diverse Indigenous groups. The Eastern, Western, and Northern Métis have distinct histories (Ens, 2016; Martel, 2018).

Eastern Métis intermarriages occurred primarily between Anishinaabe and Ojibwe peoples, while Western Métis emerged from unions between Ojibwe, nêhiyawak (Cree), Lakota, Nakoda, and Dakota peoples. Northern Métis developed a bit later — in the late 1700s — through intermarriage between Cree and Dene peoples (Ens, 2016). Each intermarriage brought linguistic complexity, including various dialects of Michif — a mixed language combining French nouns and Indigenous-language verbs (Auger, 2010). However, these distinct peoples were not called initially Métis; consistent with colonial attitudes of the era, they were often referred to as “half-breeds” (Ens, 2016).

François Beaulieu, born to a French father and a nêhiyaw-iskwêw (Cree woman), was a Métis explorer and trader revered among Northern Métis. He travelled with the Hudson’s Bay Company and guided explorers like Alexander Mackenzie and John Franklin. He married a Dene woman named Ethiba (whose name, ʔEtthíbą Tło’aze, translates to Forward-Thinking Little-Grass) and had other relationships with a nêhiyaw (Cree) wife and a Métis wife, fathering children in many communities he visited. Thus began the history of Métis in the North (Martel, 2018). (Note: This is a personal ancestral connection for me.)

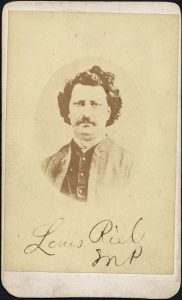

There are many notable figures in Métis history. Louis Riel is probably the most famous Métis patriarch. He led the Red River Métis, famously leading the Red River Resistance of 1869-70, which sought to protect Métis land and rights amid Canadian expansion (Ens, 2016).

What about Métis women? Like other colonial contexts, patriarchy was reinforced through Indian Act politics and Eurocolonial influence. Annie Bannatyne (1830–1908) was a Métis philanthropist and founder of early hospitals; she famously horse-whipped Englishman Charles Mair, a member of the Canada First Party in 1869, for his anti-Métis stance (Ens, 2016). Other prominent Métis women include Mathilda Davis, Harriet Cowan, and Marie Smith, whose memoirs and writings offer important firsthand insight into Métis experiences on the prairies (Ens, 2016).

Now that you know a bit about Métis and their ancestral connections, it’s essential to recognize that intergovernmental disputes exist between Indigenous nations regarding membership claims. In 2021, the Métis Nation of British Columbia, Métis Nation of Saskatchewan, and Manitoba Métis Federation withdrew from the Métis National Council. The Northwest Territory Métis Nation (of which I am a member) was never a member of the Métis National Council (Métis National Council, 2021; Northwest Territory Métis Nation, 2021). This explains why there are many different Métis governments and peoples, and why their histories can be complex. Do you remember how many Métis districts there are in Alberta?

Wait a minute — what about the Inuit?

The Inuit are the Indigenous Peoples of the coasts and islands of the Arctic Ocean. They are distinct from the more than 630 First Nations and the diverse Métis populations. Inuit ways of life — including hunting, harvesting, fishing, whaling, and living — are deeply dependent on consistent environmental patterns (Tester & Kulchyski, 1994). Interestingly, some individuals are each Inuit, First Nations, and Métis, which illustrates the complexity of Indigenous identities in Canada.

Inuit in what is now called Canada live across four main regions: the Inuvialuit Region (in the northern Northwest Territories), Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec), and Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador) (Government of Canada, 2022).

Foreign whaling in the Arctic began in the 1700s, causing a vast depletion of whale populations, with thousands of whaling ships active during that century alone (Scoresby, 1820). British whaler and explorer William Penny persuaded Eenoolooapik, the brother of an Inuk interpreter and guide, Taqulittuq, to show him the inland islands. Shortly thereafter, Cumberland Sound was established in 1850 as the first point of Arctic colonization, and mass whaling expanded inland from the Arctic coast (Penny, 1866).

Attempts to assimilate Inuit began much later than the Indian Act-era residential schools imposed on First Nations in the south. Early religious missions were established in the Arctic about two hundred years after those in southern Canada. Although residential schools operated in the Northwest Territories, which then included present-day Alberta and Nunavut, Inuit residential schools were not established across the Arctic until the 1950s and 1960s (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015).

Canada’s assertion of sovereignty over the Arctic required establishing Arctic communities and creating the appearance that Indigenous Peoples—the Inuit—were willingly present. However, this effort was complicated because Inuit were highly mobile and had not been forced onto reserves or municipalized like many First Nations or Métis peoples (Tester & Kulchyski, 1994).

Consider that in Nunavut, there are no roads connecting communities. Seasonal changes to waterways and ice made travel best suited to kayaks in summer and dog sleds in winter. The invention of the snowmobile, commercially available from the mid-1950s, revolutionized Arctic transportation, and thus, Arctic colonization (Foster & Hayden, 2005).

Between the 1950s and early 1960s, the RCMP killed thousands of Inuit sled dogs in what is now known as the Inuit Dog Sled Slaughter. This act devastated Inuit mobility and ancestral harvesting practices. Without sled dogs, Inuit travel and subsistence were severely restricted, which led to a de facto municipalization of Inuit lifestyles. Despite these challenges, Inuit today hold the highest rates of Indigenous language fluency (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2023).

Inuit have asserted their own territorial jurisdiction separate from the Northwest Territories. Nunavut became the newest Canadian territory in 1999, forming through the largest Indigenous land claims agreement in Canadian history. Nunavut is the world’s least populated territory and includes Alert—the northernmost inhabited place on earth (Government of Nunavut, 2023).

It is estimated that over a fifth of global oil lies beneath the Arctic, along with other significant mineral deposits such as copper, iron, and diamonds (Natural Resources Canada, 2022). While climate change remains politically contested in southern Canada, Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic experience its effects firsthand, relying on a clean Arctic to sustain their long-standing hunting, harvesting, whaling, and land-based lifestyles (Ford et al., 2016).

Inuit have also been early adopters of contemporary EuroWestern technologies, but always within Inuit-specific cultural, linguistic, political, and historical contexts. Inuit media use is discussed further in the next module. While Inuit could not have invented paper—given the absence of trees thousands of kilometers away—they founded their own Inuit broadcasting services in 1978, a pioneering move that you’ll read about in the following chapter (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2023).

Oh yeah, wait a second — what does any of this have to do with media?

To fully grasp the role that media plays in shaping public understanding of Indigenous Peoples, it is essential first to recognize the vast and distinct histories of these communities. Indigenous Peoples have rich, diverse cultures and histories that predate the establishment of modern nation-states like Canada by thousands of years. These histories include complex social, political, and economic systems, as well as profound relationships with their lands.

Understanding the impacts and ongoing impositions of the Canadian nation-state, including colonization, residential schools, and legal frameworks like treaties, is crucial. These forces have shaped not only Indigenous realities but also how Indigenous Peoples are portrayed, often inaccurately or incompletely, in media.

With this foundational knowledge, you will be better equipped to appreciate the early adoptions, innovations, and creative contributions of Indigenous Peoples — contributions that often get overlooked or marginalized. This deeper awareness fosters a more respectful and informed perspective that challenges simplistic or stereotypical narratives as maintained by media.

Moreover, this nuanced understanding allows you to critically analyze media representations of Indigenous Peoples, recognizing biases, stereotypes, and the power dynamics behind those portrayals. Media is not just a neutral conveyor of information; it plays an active role in shaping societal attitudes and policies toward Indigenous communities.

In upcoming chapters, we will build on this foundation by exploring methods and frameworks for analyzing media content about Indigenous Peoples with a critical eye. This will help you engage thoughtfully and ethically with Indigenous issues in media contexts.

Summary

Having a nuanced understanding of the complexities of distinct groups of people helps us be better and more conscientious media makers. Consider the thousands of Indigenous societies around the world and the hundreds of thousands of distinct Indigenous nations across so-called Canada. What makes them distinct? How are their histories different? What about worldview, spirituality, and language?

Key Takeaways

Key takeaways from this chapter include:

- Think globally, act locally: Indigeneity and colonization are global topics, but how does that affect you in Treaty 7, so-called Canada, in a media history course?

- Indigenous worldviews and spiritualities persist: Indigenous languages and ways of being have been threatened and attacked by Canada, but they hold thousands of years of history which predate colonization.

- Indigenous law and Aboriginal law: Indigenous law has thousands of years of protocol, bound within language and action; Aboriginal law was formed in Canada and emerged in the 1800s.

Indigenous Peoples worldwide are learning from each other’s stories and forming global coalitions. Changes in media and their intertwined histories have brought international scrutiny to Canada. It’s only been since World War I that Canada has pivoted away from its most heinous legislation, and only since 1997 that the last residential school closed. And yet, Indigenous Peoples have been cleverly creating media with new and emerging technologies despite these overlapping histories of attempted assimilation, colonization, and cultural genocide.

As you consider that Indigenous Peoples are global, and are affected by colonization as a worldwide process, consider how you, too, are impacted by colonization. As we move into the next module, consider: How have colonial narratives been upheld through emerging media? How has exposure to media affected your perspective on Indigenous Peoples? How will this affect you in your practice and profession as a media-maker? You’ll find your answers to these questions both in yourself and in the upcoming chapters.

Group Activity: Indigenous Foundations Deep Dive – Chapter Analysis Activity

Overview

Your group will conduct a deep analysis of the chapter, focusing on one key theme while examining how the author presents complex Indigenous histories. This activity connects directly to Truth and Reconciliation Call to Action #86 – building essential knowledge for ethical media representation.

Instructions

- Theme Selection and Chapter Review

Each group chooses one focus area and re-reads relevant chapter sections:

A. Residential Schools and Cultural Genocide

Review:”Residential schools: Beginnings, Abuses, and Justice, to RCAP, the IRSSA, and the TRC”

B. UNDRIP and Indigenous Rights

Review: “Indigenous Peoples across Canada, the United Nations, and UNDRIP” section

C. Treaty 7 Territory and Land Rights

Review: “Indigenous communities, lands, and peoples in Alberta and across Treaty 7” section

D. Legal Systems in Conflict

Review: “The big difference between Indigenous Law and Aboriginal Law” section

E. Colonial Evolution and Crown Relations

Review: “Indian Affairs: The Indian Act, Treaties, and the encroachment of Canada (1755 — 1876)” section

- Chapter Analysis Deep Dive

As you review your sections, analyze and document:

- What aspects of your theme need more explanation?

- What connections to other themes become apparent?

- How might lack of this knowledge lead to harmful media representations?

- What specific stereotypes or misconceptions does this section address?

- Why is this foundational understanding crucial for media creators?

- Create A Creative Output you can present to the class which highlights

- Key insights from your chapter sections

- Critical gaps or questions that emerge

- Why this deep knowledge is essential for ethical media practice

End-of-Chapter Activity (News Scan)

Media and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights, Law, and Representation

Purpose: This assignment helps you connect historical perspectives on Indigenous–settler relations and media representation with contemporary developments in Canada, enhancing your ability to critically assess how media portray Indigenous Peoples and how these portrayals shape public understanding of land, law, and reconciliation.

Using Google News, find a recent article (published in the last three months) about any of the following themes in Canada:

- Residential schools or their legacy

- UNDRIP (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)

- Treaties and Aboriginal and Indigenous Rights

- Aboriginal and Indigenous Law

- Indigenous–Crown relations

- Indigenous Peoples’ connection to lands, particularly across Treaty 7

- Media representation of Indigenous communities or issues

In 250 words, respond to the following:

- Summarize the Article (100-150 words)

- Provide the title, author, and date in APA format.

- Explain the article’s primary focus and significance.

- Identify key findings or arguments presented.

- Connect to Chapter Themes (100-150 words)

- Relate the article to at least one key theme from this chapter (such as legacies of residential schools, Indigenous–Crown relations, land rights, Indigenous law, or media representation of Indigenous Peoples).

- Analyze how the article illustrates continuity or change in the treatment, portrayal, or legal recognition of Indigenous Peoples compared to historical patterns discussed in the chapter.

- Explain what the article suggests about the future direction of Indigenous rights, representation, or reconciliation in Canada.

Cite your sources (textbook and article) in APA format.

Note: The full text of the article must be included upon submission as an Appendix for verification

References

Alards‑Tomalin, D., & PSYC 303 Students. (n.d.). Psychological Roots: Past and Present Perspectives in the Field of Psychology [Pressbooks]. Pressbooks.

Alberta Regional Dashboard. (2021). Percent Aboriginal population: Calgary. https://regionaldashboard.alberta.ca/region/calgary/percent-aboriginal-population/

Alfred, T. (2005). Wasáse: Indigenous pathways of action and freedom. University of Toronto Press.

Assembly of First Nations. (2023). About us. https://www.afn.ca/about-us/

Auger, M. (2010). Michif language and culture: An introduction. Métis Heritage Centre.

Bastien, B. (2004). Blackfoot ways of knowing: The worldview of the Siksikaitsitapi. University of Calgary Press.

Bastien, B. (2010). The decolonization of Indigenous knowledge in academy. In G. J. S. Dei & A. Kempf (Eds.), Anti-colonialism and education: The politics of resistance (pp. 25-38). Sense Publishers.

Betts, R. F. (1998). Decolonization. Routledge.

Blackstock, C. (2024). Child welfare and Indigenous children in Canada: A continuing crisis. First Nations Child & Family Caring Society.

Borrows, J. (2016). Freedom and Indigenous Constitutionalism. University of Toronto Press.

Bourgeon, L., Burke, A., & Higham, T. (2017). Earliest human presence in North America dated to the Last Glacial Maximum: New radiocarbon dates from Bluefish Caves, Canada. PLOS ONE, 12(1), e0169486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169486

Bryce, P. H. (1922). The story of a national crime: An appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada. James Hope & Sons.

Cardinal, H. (1999). The unjust society: The tragedy of Canada’s Indians. Douglas & McIntyre.

Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. (2017). The “Doctrine of Discovery” and terra nullius: A Catholic response. https://www.cccb.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/catholic-response-to-doctrine-of-discovery-and-tn.pdf

Cooper, F. (2002). Africa since 1940: The past of the present. Cambridge University Press.

Corntassel, J. (2008). Toward sustainable self-determination: Rethinking the contemporary Indigenous-rights discourse. Alternatives, 33(1), 105-132.

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. University of Minnesota Press.

Deloria, V., Jr. (1998). Custer died for your sins: An Indian manifesto. University of Oklahoma Press.

Diabo, L. (2021). Canada’s flawed approach to implementing UNDRIP. Indigenous Policy Journal, 32(3).

Duhamel, K. (2018, November 14). The Two Row Wampum: An Indigenous-European agreement of peace, friendship and respect. Canadian Museum for Human Rights. https://humanrights.ca/story/two-row-wampum

Ehle, J. (1988). Trail of Tears: The rise and fall of the Cherokee nation. Anchor Books.

Ens, G. (2016). Métis: Race, recognition, and the struggle for Indigenous peoplehood. University of Manitoba Press.

Estes, N. (2019). Our history is the future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the long tradition of Indigenous resistance. Verso Books.

Fisher, S. (1992). Contact and conflict: Indian-European relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890. UBC Press.

Ford, J. D., Labbé, J., Flynn, M., & Araos, M. (2016). Readiness of Indigenous communities for climate change adaptation: A case study from the Canadian Arctic. Global Environmental Change, 39, 64-75.

Foster, J., & Hayden, R. (2005). Snowmobiles and northern communities: A history. Arctic Institute of North America.

Gismondi, M. (2020, May 2). The untold story of the Hudson’s Bay Company: A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe. Canadian Geographic. https://canadiangeographic.ca/articles/the-untold-story-of-the-hudsons-bay-company/

Government of Alberta. (2023). Métis Settlements locations. https://www.alberta.ca/metis-settlements-locations

Government of Canada. (2018). Treaty 7. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028793/1564415262269

Government of Canada. (2021). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act: Canada’s vision. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/ap-pa/ah/p1.html#vision

Government of Canada. (2022). Inuit in Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100014610/1539264007997

Government of Nunavut. (2023). About Nunavut. https://gov.nu.ca

Henige, D. (1978). On the contact population of Hispaniola: History as higher mathematics. Hispanic American Historical Review, 58(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-58.2.217

Historica Canada. (2017). Confederation, 1867. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/confederation-1867

Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. (2006). Schedule N: Mandate for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. https://www.residentialschoolsettlement.ca/SCHEDULE_N.pdf

Indigenous Services Canada. (n.d.). First Nation Profiles Interactive Map. https://geo.sac-isc.gc.ca/cippn-fnpim/index-eng.html

International Labour Organization. (1989). Convention concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (No. 169). https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C16

International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. (2019, January 28). International Year of Indigenous Languages. https://iwgia.org/en/news/3302-year-of-indigenous-languages.html

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2021). Who we are. https://www.itk.ca/who-we-are/

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2023). Inuit in Canada. https://www.itk.ca

Johansen, B. E., & Mann, C. C. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Greenwood Publishing Group.

Jones, A., Masuda, J. R., Morgan, A., & Chew, D. (2021). Forced sterilization of Indigenous women in Canada: A critical analysis of law, policy and colonial power. Global Public Health, 16(3), 383-398.

Kahn, D. (2009). Code talkers. HarperCollins.

Klassen, P. (2000). “Little savages”: Children and violence in the Canadian West. University of British Columbia Press.

Koch, A., Brierley, C., Maslin, M. M., & Lewis, S. L. (2019). Earth system impacts of the European arrival and the Great Dying in the Americas after 1492. Quaternary Science Reviews, 207, 13-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004

Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. University of Toronto Press.

Lacas, M. M. (1952). The encomienda in Latin-American history: A reappraisal. The Americas, 8(3), 259-287. https://doi.org/10.2307/978373

Leslie, J. (1978). The enfranchisement of Indians, 1839–1969. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Treaties and Historical Research Centre.

Leslie, J. (2002). The historical development of the Indian Act. In J. R. Miller (Ed.), Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Indian-White Relations in Canada (3rd ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Library and Archives Canada. (1879). Claim of Elias Hill, Mohawk, for compensation for lands and losses [Government document].

Lyons, O., Mohawk, J., Deloria, V., Jr., Berman, H., & Hauptman, L. (1992). Exiled in the land of the free: Democracy, Indian nations, and the U.S. Constitution. Clear Light Publishers.

Martel, D. (2018). Métis history and culture. In W. Stinson & J. B. Wright (Eds.), Indigenous Peoples and Canadian History (pp. 134-157). Canadian Scholars Press.

McCallum, M. J. (2002). Indigenous women, work, and history. University of Manitoba Press.

McHugh, P. G. (2004). Maori and international law. In M. Langton (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Indigenous Studies. Oxford University Press.

McNeil, K. (2018). Indigenous legal traditions and Canadian law. In P. G. McHugh & A. H. L. Stassen (Eds.), Aboriginal Peoples and the Law (pp. 45-68). Oxford University Press.

Metcalf, B. D., & Metcalf, T. R. (2006). A concise history of modern India. Cambridge University Press.

Métis National Council. (2021). Press release on Métis Nation provincial members’ withdrawal. https://www.metisnation.ca

Métis National Council. (2023). About us. https://www.metisnation.ca/

Métis Nation of the Northwest Territories. (2021). About us. https://www.mnwt.com/

Métis Settlements General Council. (n.d.). Governance and districts. https://albertametis.com/governance/districts/

Miller, J. R. (2000). Skyscrapers hide the heavens: A history of Indian-white relations in Canada (3rd ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Miller, J. R. (2009). Compact, contract, covenant: Aboriginal treaty-making in Canada. University of Toronto Press.

Milloy, J. S. (1999). A national crime: The Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986. University of Manitoba Press.

Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations. (2024). Statement on the Inuit sled dog slaughter. https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2024/03/statement-on-the-inuit-sled-dog-slaughter.html

Mosby, I. (2013). Administering colonial science: Nutritional research and human biomedical experimentation in Aboriginal communities and residential schools, 1942–1952. Histoire sociale/Social History, 46(91), 145-172. https://doi.org/10.1353/his.2013.0015

Natural Resources Canada. (2022). Minerals and energy in the Arctic. https://www.nrcan.gc.ca

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. James Currey.

Niezen, R. (2003). The origins of indigenism: Human rights and the politics of identity. University of California Press.

Okediji, R. L. (2018). Traditional knowledge and the public domain (CIGI Papers No. 176). Centre for International Governance Innovation. https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/Paper%20no.176web.pdf

Pakenham, T. (1991). The scramble for Africa: White man’s conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. Random House.

Penny, W. (1866). The Arctic whaling voyages of William Penny. Smith, Elder & Co.

Perdue, T., & Green, M. D. (2005). The Cherokee removal: A brief history with documents (2nd ed.). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Power, S. (2002). “A problem from hell”: America and the age of genocide. Basic Books.

Pratt, R. H. (1973). The advantages of mingling Indians with whites. In F. P. Prucha (Ed.), Americanizing the American Indians: Writings by the “Friends of the Indian” 1880–1900 (pp. 260-271). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1892)

Ray, A. J. (1998). Indians in the fur trade: Their role as hunters, trappers and middlemen in the lands southwest of Hudson Bay, 1660-1870. University of Toronto Press.

Sandlos, J., & Keeling, A. (2016). Aboriginal communities, traditional ecological knowledge, and the environmental legacies of extractive development in Canada. Extractive Industries and Society, 3(2), 278-287.

Schwab, K. (2017). The fourth industrial revolution. Crown Business.

Scoresby, W. (1820). An account of the Arctic whaling voyages. Longman.

Senate of Canada. (2024). Bill to outlaw forced sterilization debated in Senate. https://sencanada.ca/en/newsroom/forced-sterilization-bill

Simpson, L. B. (2014). Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence. ARP Books.

Sinclair, R. (2007). Identity lost and found: Lessons from the sixties scoop. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3(1), 65-82.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. (n.d.). What does it mean to be human? https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-evolution-timeline-interactive

Stannard, D. E. (1992). American holocaust: The conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press.

Statistics Canada. (2019). Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022). Indigenous population: Children and youth. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2022045-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2024). Children and youth in care: National and provincial/territorial estimates. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/41-20-0002/412000022024001-eng.htm

Tester, F. J., & Kulchyski, P. (1994). Tammarniit (Mistakes): Inuit relocation in the Eastern Arctic, 1939-63. UBC Press.

Todorov, T. (1984). The conquest of America: The question of the other. Harper & Row.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf

United Nations. (1948). Convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide. https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.1_Convention%20on%20the%20Prevention%20and%20Punishment%20of%20the%20Crime%20of%20Genocide.pdf

United Nations. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

United Nations. (n.d.). Working Group on Indigenous Populations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/working-group-on-indigenous-populations.html

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (2020). Factsheet: Indigenous peoples, Indigenous voices. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf

United States Senate. (1987). Influence of Iroquois Confederacy on U.S. Constitution. Hearings, 100th Congress. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-100shrg83712/pdf/CHRG-100shrg83712.pdf

Weaver, H. N. (2013). Traditional healing in historical perspective. In H. N. Weaver (Ed.), Voices of First Nations people: Human services considerations (pp. 131-156). Routledge.

Whiskeyjack, L., & Napier, K. (2020). Reconnecting to the spirit of the language: Learning nêhiyawêwin to connect with the land. Briarpatch, 49(5), 26-37.

Wicken, W. C. (2011). Mi’kmaq treaties on trial: History, land and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

Media Attributions

- An Accurate Map of the Territories of the Hudson’s Bay Company in North America (John Hodgson 1791)

- Display on Haudenosaunee Confederacy – Liverpool – New York – USA – 01

- louis riel