5.5 Chain of Transmission

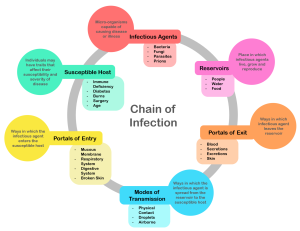

The chain of transmission, also referred to as the chain of infection, describes the infection process. There are six links in the chain:

- Infectious agent

- Reservoir

- Portal of exit

- Mode of transmission

- Portal of entry

- Susceptible host

You need to understand how an infectious agent travels throughout the cycle to determine how to break the chain and prevent the transmission of the infectious disease. If a part of the chain of transmission is broken, the infection will not occur. Routine practices and additional precautions are used to break or minimize the chain of transmission. Figure 5.13 below provides an image of the chain of infection and its key components.

Infectious Agent

An infectious agent, also known as a pathogen, causes disease in the host. The most common infectious agents are bacteria, viruses, and fungi; however, infectious agents also include other pathogens such as parasites and prions.

Examples of infectious agents include the following:

- Bacteria: Streptococcus and salmonella

- Viruses: Influenza and chickenpox

- Fungi: Athlete’s foot and thrush mouth in newborns

- Parasites: Malaria, giardia, and toxoplasmosis

- Prions: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Pathogens can live inside a host or live in a dormant phase outside a living host with the ability to invade the body. They often have an elaborate adaptation that helps them exploit a host’s biology, behaviour, and ecology to live in and move between hosts. The presence of a pathogen does not predict the onset of an infection; instead, the chain of transmission must be present. Knowing how long an infectious agent can survive in the environment is important. For example, influenza can live up to 48 hours on inanimate objects, whereas C. difficile spores can survive for months to years on inanimate objects if the surface is not cleaned properly. People who have been infected with an infectious agent may present clinical symptoms according to that pathogen. However, other individuals may be asymptomatic and show no signs or symptoms of the infection.

Reservoir

The reservoir can be a living organism or inanimate object in or on which an infectious agent lives, survives, and has the ability to multiply and grow. Reservoirs can be people, animals, insects, food, soil, or water. Human reservoirs of a pathogen may or may not be capable of transmitting the pathogen, depending on the stage of infection and the pathogen.

Examples of reservoirs include the following:

- People: The influenza virus can live in a client’s upper respiratory tract—nose, mouth, throat, and sometimes lungs—and up to 48 hours outside the body on inanimate objects after being spread through sneezing.

- Animals: The rabies virus can be transmitted when an infected animal bites a person. This virus cannot live outside the host.

- Mosquitoes: Mosquitoes can carry malaria parasites and can infect humans (Figure 5.14).

- Food: Food can become contaminated by the poor hygiene of humans, improper washing of food items, undercooking, or through cross-contamination. A food-borne infection can cause gastrointestinal issues if contaminated food is consumed.

- Soil: Soil can contain a fungal pathogen called blastomycosis or bacteria such as tetanus. If humans breathe in the spores, they can become infected.

- Water: Giardia parasites live in contaminated water and can infect humans if consumed.

Portal of Exit

The portal of exit is how an infectious agent leaves the reservoir or host. When the infectious agent exits the body and enters a host’s eyes, nose, or mouth, or contaminates an inanimate surface, the potential for transmitting the infectious agent exists.

Portals of exit can include the following:

- The mouth via secretions of saliva or when a client vomits

- The respiratory tract when a client’s secretions exit by sneezing, coughing, talking, or laughing

- Skin lesions via blood or exudate

- The gastrointestinal and genitourinary or urogenital tracts when a client excretes urine, feces, semen, or vaginal secretions

Mode of Transmission

The mode of transmission is how the infectious agent travels and spreads from one person to another, either directly or indirectly.

Modes of transmission include the following:

- Contact transmission: Contact transmission occurs directly by touching an infectious client with your hands or indirectly by touching items or medical equipment that is contaminated with the infectious agent. If the client is on contact precautions, for MRSA or Staphylococcus aureus for example, you need to wear gloves and a gown if your skin or clothing will come into direct or indirect contact with the client or the contaminated environment.

- Droplet transmission: Droplet transmission occurs through respiratory secretions from talking, sneezing (Figure 5.15), coughing, or laughing; droplets can travel up to 2 metres. If the client is on droplet precautions, for example, for influenza, pertussis, rubella, or mumps, you need to wear a mask and eye protection.

- Airborne transmission: Airborne transmission occurs through small nuclei travelling on air currents for long distances—distances over 2 metres. If the client is on airborne precautions, for example, for tuberculosis, the client must be placed in a negative-pressure room and you must wear a fit-tested N95 respirator.

- Vehicle transmission: Vehicle transmission occurs through vehicles such as water, food, or air.

- Vector transmission: Vector transmission occurs through living organisms that can transmit the infectious agent between humans biologically, such as mosquitoes. Mechanical transmission from an animal to a human can occur via flies or ticks.

Portal of Entry

The portal of entry is how an infectious agent enters another person’s body or a new host. Infectious agents can enter the body through the mucous membranes of the client’s eyes, nose, mouth, or skin lesions, or through open wounds.

Examples of portals of entry include the following:

- An infectious agent can enter a client’s body via a catheter, gastronomy tube, intravenous catheter, or other invasive device.

- Bacteria can enter through the non-intact skin of clients or healthcare providers.

- A virus can enter the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, mouth, and respiratory tract when another person coughs or sneezes without covering their nose or mouth and is within 2 metres of another person.

- A virus can enter a person’s digestive system if they eat contaminated food.

Susceptible Host

A susceptible host is anyone who is at risk of an infectious agent. Some individuals are more susceptible than others. Newborns, children up to five years old, pregnant women, adults over 65 years old, people undergoing invasive procedures and complex treatments, people with compromised immune systems or chronic illness, and unimmunized people are more susceptible to being infected. You need to be aware of factors that increase a client’s risk of becoming colonized or infected in the healthcare facility. Increased age, use of invasive procedures, an immunocompromised state, greater exposure to microorganisms, and an increased use of antimicrobial agents and complex treatments are common risk factors.

When an infectious agent enters a susceptible host, the reaction from the pathogen is not the same for everyone. Symptoms can vary from person to person. A person may not present any symptoms, known as being asymptomatic, or they can be symptomatic and present different symptoms.

To stop the transmission of an infectious agent, at least one link must be broken; the routine practices and policies that can break the chain will be discussed in the next page. When consistently followed, infection prevention and control measures can eliminate infectious agent transmission.

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been adapted from the following resource:

Hughes, M., Kenmir, A., St-Amant, O., Cosgrove, C., & Sharpe, G. (2021). Introduction to infection prevention and control practices for the interprofessional learner. eCampusOntario. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/introductiontoipcp/, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Image Credits

(Images are listed in order of appearance)

Chain of Infection by Genieieiop, CC BY-SA 4.0

Aedes aegypti CDC-Gathany by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Public domain

Sneeze by James Gathany, CDC Public Health Image Library Image, Public domain