4.5 Viruses, Fungi, and Prions

Viruses

Viruses are distinct biological entities; however, their evolutionary origin is still a matter of speculation. They are not included in the “tree of life” because they are acellular. In order to survive and reproduce, viruses must infect a cellular host, making them obligate intracellular parasites. The genome of a virus enters a host cell and directs the production of the viral components, proteins and nucleic acids, needed to form new virus particles called virions. New virions are made in the host cell by the assembly of viral components. Then the new virions transport the viral genome to another host cell to carry out another round of infection. Below you will find a summary of some of the key characteristics of viruses and also a very detailed video that discusses viral structure and function.

Important characteristics of viruses:

- Infectious, acellular pathogens

- DNA or RNA genome (never both)

- Obligate intracellular parasites with host and cell-type specificity

- Genome is surrounded by a protein capsid and, in some cases, a phospholipid membrane studded with viral glycoproteins

- Lack genes for many products needed for successful reproduction, requiring exploitation of host-cell genomes to reproduce

(Osmosis from Elsevier, 2020)

How Viruses Spread

Viruses can infect every type of host cell, including those of plants, animals, fungi, protists, bacteria, and archaea. Most viruses will only be able to infect the cells of one or a few species of organisms. This is called the host range. However, having a wide host range is not common, and viruses typically only infect specific hosts and only specific cell types within those hosts. The viruses that infect bacteria are called bacteriophages. The word phage comes from the Greek word for “devour.” Other viruses are just identified by their host group, such as animal or plant viruses. Once a cell is infected, the effects of the virus can vary depending on the type of virus. Viruses may cause abnormal growth of cells or cell death, alter a cell’s genome, or cause little noticeable effect in cells.

Viruses can be transmitted through direct contact, indirect contact with fomites, or through a vector, such as an animal that transmits a pathogen from one host to another. Arthropods such as mosquitoes, ticks, and flies, are typical vectors for viral diseases, and they may act as either mechanical vectors or biological vectors. Mechanical transmission occurs when an arthropod carries a viral pathogen on the outside of its body and transmits it to a new host by physical contact. Biological transmission occurs when an arthropod carries a viral pathogen inside its body and transmits it to the new host through biting.

In humans, a wide variety of viruses are capable of causing various infections and diseases. Some of the deadliest emerging pathogens in humans are viruses, yet we have few treatments or drugs to deal with viral infections, making them difficult to eradicate.

Viruses that can be transmitted from an animal host to a human host are called zoonoses. For example, the avian influenza virus originates in birds but can cause disease in humans. Reverse zoonoses are caused by infection of an animal by a virus that originated in a human.

Characteristics of Viruses

In general, virions (viral particles) are small and cannot be observed using a regular light microscope. They are much smaller than prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, an adaptation that allows viruses to infect these larger cells. The size of a virion can range from 20 nm for small viruses up to 900 nm for typical, large viruses. Recent discoveries, however, have identified new giant viral species, such as Pandoravirus salinus and Pithovirus sibericum, with sizes approaching that of a bacterial cell.

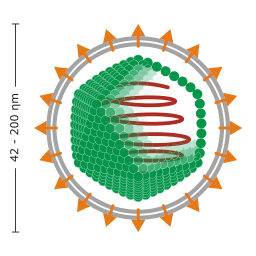

There are two categories of viruses based on general composition. Viruses formed from only a nucleic acid and capsid are called naked viruses or nonenveloped viruses. Hydrophilic viruses, such as hepatitis A or rhinoviruses, are an example because they lack an envelope. Viruses formed with a nucleic-acid-packed capsid surrounded by a lipid layer are called enveloped viruses. Lipophilic viruses, such as ebola, herpes, or measles, are examples of this type of virus because they have an envelope. The viral envelope is a small portion of phospholipid membrane obtained as the virion buds from a host cell. The viral envelope can either be intracellular or cytoplasmic in origin.

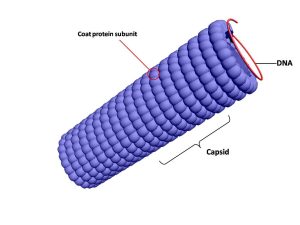

Viruses come in two basic shapes, though the overall appearance of a virus can be altered by the presence of an envelope, if present (Bruslind, 2019). Helical viruses have an elongated tube–like structure, with the capsomers arranged helically around the coiled genome and is shown in Figure 4.7. Icosahedral viruses have a spherical shape, with icosahedral symmetry consisting of 20 triangular faces (Bruslind, 2019). Figure 4.8 provides an example of an icosahedral enveloped virus. The simplest icosahedral capsid has three capsomers per triangular face, resulting in 60 capsomers for the entire virus. Some viruses do not neatly fit into either of these two categories because they are unusual in design or components, so there is a third category known as complex viruses. Examples include the poxvirus, which has a brick-shaped exterior and a complicated internal structure, as well as bacteriophages, which have tail fibres attached to an icosahedral head (Bruslind, 2019).

Fungi

Fungi (singular: fungus) are also eukaryotes. Some multicellular fungi, such as mushrooms, resemble plants, but they are actually quite different. Fungi are not photosynthetic, and their cell walls are usually made out of chitin rather than cellulose. Fungal infections can vary greatly and can be superficial, below the skin (subcutaneous), systemic, or more opportunistic in nature, often infecting someone who is immunocompromised.

Unicellular fungi, such as yeasts, are included in the study of microbiology, and there are more than 1,000 known species. Yeasts are found in many different environments, from the deep sea to the human navel. Some yeasts have beneficial uses, such as causing bread to rise and beverages to ferment, but yeasts can also cause food to spoil. Some even cause diseases, such as vaginal yeast infections and oral thrush.

Other fungi of interest to microbiologists are multicellular organisms called moulds. Moulds are made up of long filaments that form visible colonies. They are found in many different environments, from soil to rotting food to dank bathroom corners. Moulds play a critical role in the decomposition of dead plants and animals, but some can cause allergies, and others produce disease-causing metabolites called mycotoxins. Moulds have been used to make pharmaceuticals, including penicillin, which is one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics, and cyclosporine, which is used to prevent organ rejection following a transplant.

Prions

Prions do not fit neatly into any particular category of microorganism. Like viruses, prions are not found on the “tree of life” because they are acellular. They are extremely small—about one-tenth the size of a typical virus. They contain no genetic material and are composed solely of a type of abnormal protein.

At one time, scientists believed that any infectious particle must contain DNA or RNA. Then, in 1982, Stanley Prusiner, a medical doctor studying scrapie (a fatal, degenerative disease in sheep) discovered that the disease was caused by proteinaceous infectious particles, or prions. Because proteins are acellular and do not contain DNA or RNA, Prusiner’s findings were originally met with resistance and skepticism; however, his research was eventually validated, and he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1997.

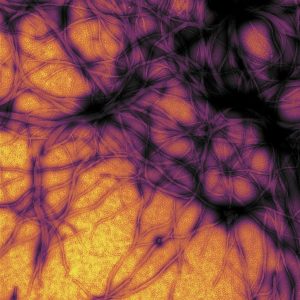

A prion is a misfolded, rogue form of a normal protein (PrPc) found in a cell and is shown in Figure 4.9. This rogue prion protein (PrPsc), which may be caused by a genetic mutation or occur spontaneously, can be infectious, stimulating other normal proteins to become misfolded, forming plaques. Today, prions are known to cause various forms of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) in human and animals. TSE is a rare degenerative disorder that affects the brain and nervous system. The accumulation of rogue proteins causes the brain tissue to become sponge-like, killing brain cells and forming holes in the tissue, leading to brain damage, loss of motor coordination, and dementia. Infected individuals will eventually become unable to move or speak. There is no cure, and the disease progresses rapidly, eventually leading to death within a few months or years.

Prions are extremely difficult to destroy because they are resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation. Even standard sterilization procedures do not ensure the destruction of these particles, and they can even remain infectious for years in their dried state. Currently, there is no treatment or cure for TSE disease, and contaminated meats or infected animals must be handled according to federal guidelines to prevent transmission. Other diseases, caused by prions, that can infect humans include Creutzfeld-Jacob disease, kuru, Alpers syndrome, and fatal familial insomnia.

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been adapted from the following resource:

Parker, N., Schneegurt, M., Tu, A.-H. T., Lister, P., & Forster, B. M. (2016). Microbiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/microbiology licensed under CC BY 4.0

References

Bruslind, L. (2019). General microbiology. https://open.oregonstate.education/generalmicrobiology/, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Osmosis from Elsevier. (2020, July 23). Viral structure and functions [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O1TetEto1Is

Image Credits

(Images are listed in order of appearance)

Helical capsid by Arionfx, CC BY-SA 3.0

Non-enveloped icosahedral virus by Nossedotti, CC BY-SA 3.0

Prion Protein Fibrils (8656058266) by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), CC BY 2.0

A type of microorganism that is not composed of cells

The genetic material found within an organism

Objects that may carry infections

Protein-coated outer layer of a virus

Subunits of the capsid, the outer covering that protects the genetic material of a virus

Composed of more than one cell

An aminopolysaccharide polymer

Affecting the whole body