4.4 Bacteria

A number of different forms of microorganisms are found thoughout the world, and some of them have been discussed already in this chapter. Although there are bacteria, protozoa, viruses, fungi, rickettsia, chlamydia, and many others, the focus of discussion in the next few pages of this book will be the ones we are most concerned with in the hospital setting.

Bacteria are found in nearly every habitat on earth, including within and on humans. Most bacteria are harmless or helpful, but some are pathogens, causing disease in humans and other animals. Bacteria are prokaryotic because their genetic material (DNA) is not held within a nucleus. There are many different types of bacteria, and among these types there is great diversity in their characteristics and ability to live in different environments. They have a wide range of metabolic capabilities and can grow in a variety of environments, using different combinations of nutrients. For example, some bacteria are photosynthetic, such as oxygenic cyanobacteria and green non-sulfur bacteria; these bacteria use energy derived from sunlight, and fix carbon dioxide for growth. Other types of bacteria are non-photosynthetic, obtaining their energy from organic or inorganic compounds in their environment. Some examples of the different forms of bacteria and the manner in which they can categorized will be discussed below.

Gram Positive and Gram Negative

- Gram positive bacteria are surrounded by a single, thick peptidoglycan cell wall.

- Gram negative bacteria have a thinner peptidoglycan cell wall, but they also have an outer membrane that contains lipopolysaccharides (which is a group of molecules) surrounding the cell.

Gram staining is a procedure used to differentiate between these two types of bacteria. In the microbiology lab, a specimen will be analyzed to concentrate any cells in a sediment, and then this sediment will be smeared on a slide and stained with a gram stain. During the gram stain process, the gram positive bacteria become purple (crystal violet), whereas the red, safranin-dyed cells are gram negative. Figure 4.5 illustrates gram positive bacteria, with its purple colouring, and gram negative bacteria with red colouring and two layers.

Besides their differing interactions with dyes and decolourizing agents, the chemical differences between gram positive and gram negative cells have other clinically relevant implications. Gram staining can help clinicians classify bacterial pathogens in a sample into categories associated with specific properties. For example, gram negative bacteria tend to be more resistant to certain antibiotics than gram positive bacteria.

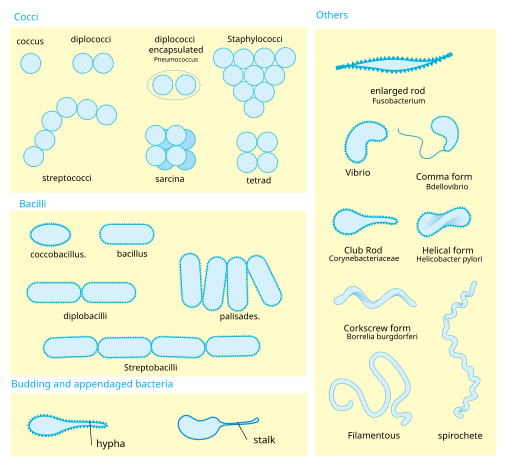

Bacteria Shapes

Bacteria typically display a number of varying shapes, or cell morphologies. The shape dictates how that cell will grow, reproduce, obtain nutrients, and move, and it is important for the cell to maintain that shape to function properly (Bruslind, 2019). Cell morphology can be used as a characteristic to assist in identifying particular microorganisms, but it is important to note that cells with the same morphology are not necessarily related (Bruslind, 2019). Some of the more common cell morphologies are shown below in Figure 4.6, and important aspects are discussed below the figure as well.

Key Concepts

Some of the common shapes of bacteria include the following:

- Coccus (pl. cocci): A spherically shaped cell.

- Bacillus (pl. bacilli): A rod-shaped cell.

- Curved rods: A rod with some type of curvature. There are three sub-categories: vibrio, which are rods with a single curve, and spirilla and spirochetes, which are rods that form spiral shapes.

- Pleomorphic: Organisms that exhibit variability in their shape.

(Bruslind, 2019)

Additional shapes can beseen for bacteria, and an even wider array for the archaea, which have even been found as star or square shapes (Bruslind, 2019). Eukaryotic microbes also tend to exhibit a wide array of shapes, particularly the ones that lack a cell wall, such as the protozoa (Bruslind, 2019).

Antimicrobial Resistance

Antimicrobial resistance is not a new phenomenon. In nature, microbes are constantly evolving in order to overcome the antimicrobial compounds produced by other microorganisms. Human development of antimicrobial drugs and their widespread clinical use has provided another selective pressure that promotes further evolution. Several important factors can accelerate the evolution of drug resistance. These include the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials, inappropriate use of antimicrobials, subtherapeutic dosing, and patient noncompliance with the recommended course of treatment.

From a clinical perspective, our greatest concerns are multidrug-resistant microbes (MDRs) and cross-resistance. MDRs are also known as “superbugs” and carry one or more resistance mechanism(s), making them resistant to multiple antimicrobials. In recent years, several clinically important superbugs have emerged.

Many strains of Staphylococcus aureus have developed resistance to antibiotics. Some antibiotic-resistant strains are designated as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA). Methicillin, which is a semisynthetic penicillin, was initially designed to treat bacteria that were already resistant. Unfortunately, soon after the introduction of methicillin to clinical practice, methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus appeared and started to spread. These strains are some of the most difficult to treat because they exhibit resistance to nearly all available antibiotics, not just methicillin and vancomycin. Because they are difficult to treat with antibiotics, infections can be lethal. MRSA and VRSA are also contagious, posing a serious threat in hospitals, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, and other places where there are large populations of elderly, bedridden, and/or immunocompromised patients. The video below provides a thorough discuss of “superbugs” and the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

(Be Smart, 2015)

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been adapted from the following resource:

Parker, N., Schneegurt, M., Tu, A.-H. T., Lister, P., & Forster, B. M. (2016). Microbiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/microbiology licensed under CC BY 4.0

References

Be Smart. (2015, April 15). Antibiotic resistance and the rise of superbugs [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyRyZ1zKtyA

Bruslind, L. (2019). General microbiology. https://open.oregonstate.education/generalmicrobiology/, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Image Credits

(Images are listed in order of appearance)

Gram Staining Bacteria by Scientific Animations, CC BY-SA 4.0

Bacterial morphology diagram by LadyofHats, Public domain