4.3 The Cell

Life takes many forms, from giant redwood trees towering hundreds of feet in the air to the tiniest known microbes, which measure only a few billionths of a metre. Humans have long pondered life’s origins and debated the defining characteristics of life, but our understanding of these concepts has changed radically since the invention of the microscope. In the 17th century, observations of microscopic life led to the development of cell theory—the idea that the fundamental unit of life is the cell, that all organisms contain at least one cell, and that cells only come from other cells.

Types of Cells

Cells vary significantly in size, shape, structure, and function. At the simplest level of construction, all cells possess a few fundamental components. These include cytoplasm, which is contained within a plasma membrane (also called a cell membrane or cytoplasmic membrane); one or more chromosomes, which contain the genetic blueprints of the cell; and ribosomes, which are organelles used for the production of proteins.

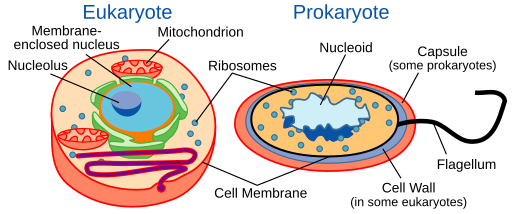

Beyond these basic components, cells can vary greatly among organisms, and even within the same multicellular organism. The two largest categories of cells—prokaryotic cells and eukaryotic cells—are defined by major differences in several cell structures (Figure 4.3). Prokaryotic cells lack a nucleus surrounded by a complex nuclear membrane and generally have a single, circular chromosome located in a nucleoid. Eukaryotic cells have a nucleus surrounded by a complex nuclear membrane that contains multiple, rod-shaped chromosomes. All plant and animal cells are eukaryotic. Some microorganisms are composed of prokaryotic cells, whereas others are composed of eukaryotic cells. The video below will give you a thorough overview of the differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

(RicochetScience, 2015)

Cell Structures and Characteristics

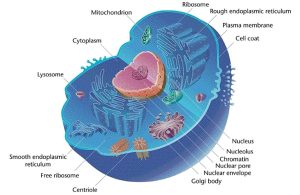

The structures inside a cell are similar to the organs inside a human body, with unique structures suited to specific functions. Figure 4.4 provides an illustration of some of the most common structures found within cells. Some of the structures found in prokaryotic cells are similar to those found in some eukaryotic cells, whereas others are unique to prokaryotes. Although there are some exceptions, eukaryotic cells tend to be larger than prokaryotic cells. The comparatively larger size of eukaryotic cells dictates the need to compartmentalize various chemical processes within different areas of the cell, using complex membrane-bound organelles. In contrast, prokaryotic cells generally lack membrane-bound organelles; however, they often contain inclusions that compartmentalize their cytoplasm. The main components of cells and their key characteristics are discussed below.

Organelles

Organelles are small structures floating in the cytoplasm of a cell. There are many different kinds found within cells, and each has a different structure and function. Some examples include the following:

- Lysosome: Contains digestive enzymes

- Vacuole: Stores materials such as water, salts, proteins, and carbohydrates

- Golgi apparatus: Tags vesicles and proteins to help them get carried to their correct destinations

- Mitochondria: Produces energy for the cell and breaks down carbohydrates and lipids to form the molecule ATP.

- Nucleus: Surrounded by a complex nuclear membrane that houses deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), ultimately controls all the cell’s activities and also serves an essential role in reproduction and heredity

- Nucleolus: A dense region within the nucleus where the assembly of ribosomes begins; the ribosomes are then transported out to the cytoplasm, where ribosome assembly is completed

- Endoplasmic reticulum: A system of metabolic processes (smooth ER) and protein manufacturing ribosomes (rough ER)

- Ribosomes: Translates ribonucleic acid (RNA) into proteins

- Peroxisome: Vesicles that defend (or neutralize) the cell from free radicals

Proteins

Proteins are polymers formed by the linkage of a very large number of amino acids. They perform many important functions in a cell, serving as nutrients and enzymes; store molecules for carbon, nitrogen, and energy; and provide structural components. The cytoplasm, for example, is the largest part of the cell and is mainly composed of protein.

Spore Coat

Plasma Membrane

The plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells, which separates the interior of the cell from the outside environment, is similar in structure to the prokaryotic plasma membrane in that it is composed mainly of phospholipids, which form a bilayer with embedded proteins.

Cell Wall

In addition to a plasma membrane, some eukaryotic cells have a cell wall. The cells of fungi, algae, and plants have cell walls. Depending upon the type of eukaryotic cell, cell walls can be made of a wide range of materials, including cellulose (plants); biogenic silica, calcium carbonate, agar, and carrageenan (protists and algae); or chitin (fungi). In general, all cell walls provide structural stability for the cell and protection from environmental stresses such as desiccation, changes in osmotic pressure, and traumatic injury.

Cell Shape

Eukaryotic cells display a wide variety of different cell morphologies. Possible shapes include spheroid, ovoid, cuboidal, cylindrical, flat, lenticular, fusiform, discoidal, crescent, ring stellate, and polygonal. Some eukaryotic cells are irregular in shape, and some are capable of changing shape. The shape of a particular type of eukaryotic cell may be influenced by factors such as its primary function, the organization of its cytoskeleton, the viscosity of its cytoplasm, the rigidity of its cell membrane or cell wall (if it has one), and the physical pressure exerted on it by the surrounding environment and/or adjoining cells.

Requirements for Cell Life

There are certain requirements for cell life. and these will varying depending on the type of cell. As you will see below, certain cells require particular parameters. whereas others require the opposite to survive and also thrive.

Oxygen: The growth of cells will vary depending on oxygen requirements. For example, some bacteria are obligate (strict) aerobes, which means they cannot grow without an abundant supply of oxygen. On the other hand, there are also obligate anaerobes, which are killed by oxygen. Facultative anaerobes are organisms that thrive in the presence of oxygen, but also grow in its absence by relying on fermentation or anaerobic respiration.

Nutrition: This is needed to provide energy for cell activities. Sources of nutrition will vary depending on the type of cell, but it can come from a variety of sources such as blood, bodily waste, and other resources found in the environment.

Moisture: Cells depend on available water to grow. Bacteria, for example, require high levels of moisture, whereas fungi can tolerate drier environments.

Chemical balance: The optimum growth pH is the most favourable pH for the growth of an organism. The lowest pH value that an organism can tolerate is called the minimum growth pH, and the highest pH is the maximum growth pH. For example, most bacteria are neutrophiles, meaning that they grow optimally at a pH within one or two pH units of the neutral pH of 7. Microorganisms that grow optimally at pH less than 5.55 are called acidophiles. At the other end of the spectrum are alkaliphiles, microorganisms that grow best at a pH between 8.0 and 10.5.

Key Concept

Most familiar bacteria, like Escherichia coli, staphylococci, and Salmonella spp. are neutrophiles and do not fare well in the acidic pH of the stomach. However, there are pathogenic strains of E. coli, S. typhi, and other species of intestinal pathogens that are much more resistant to stomach acid. By comparison, fungi thrive at slightly acidic pH values of 5.0–6.0.

Temperature: Microorganisms thrive at a wide range of temperatures; they have colonized different natural environments and have adapted to extreme temperatures. Psychrophiles grow best in the temperature range of 0–15°C, whereas psychrotrophs thrive between 4°C and 25°C. Mesophiles grow best at moderate temperatures in the range of 20°C to about 45°C. Thermophiles and hyperthermophiles are adapted to life at temperatures above 50°C.

Darkness/Light: Certain bacteria, such as photosynthetic bacteria, depend on visible light for energy. Photoautotrophs, such as cyanobacteria or green sulphur bacteria, and photoheterotrophs, such as purple non-sulphur bacteria, depend on sufficient light intensity at the wavelengths absorbed by their pigments to grow and multiply. Energy from light is captured by the pigments and converted into chemical energy. Other microorganisms, such as the archaea of the class Halobacteria, use light energy to drive their proton and sodium pumps.

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been adapted from the following resource:

Parker, N., Schneegurt, M., Tu, A.-H. T., Lister, P., & Forster, B. M. (2016). Microbiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/microbiology licensed under CC BY 4.0

References

(Images are listed in order of appearance)

Celltypes by Science Primer (National Center for Biotechnology Information), Public domain

A gel-like substance enclosed by the cell membrane; contains the organelles

Composed of more than one cell

Small molecules essential to all life

A network of protein fibres that maintains or modifies a cell's shape and ensures mechanical resistance to deformation