Section 5: Important Moves in Academic Writing

Writing Strong Introductions and Conclusions

The Beginning and the End

Think about the compositions that you have encountered today. Have you listened to a podcast? Watched an ad on YouTube? Played a story-based video game? The creators of all these compositions have considered how to begin and how to end their compositions in a way that makes their work satisfying to you as their audience.

All compositions consist of an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction and conclusion work together to make a composition coherent. The introduction is an invitation to the reader to enter the world of your thoughts, and the conclusion is your goodbye to the reader: You leave the reader with new ideas and understanding of the world before you set them on their way. The introduction sets up the journey for the reader, and the conclusion ends it, but they are part of the same journey, and the reader should sense this.

As you start to think about your introduction and conclusion, consider the conventions of the genre in which you are writing. Different genres have different ways to begin and end, and the best way to learn these conventions is to pay attention to how other creators and authors do it. If you are creating a podcast, for example, listen to the introductions and conclusions of several of your favourite episodes. What strategies do the podcast authors use to make their compositions begin and end well? This same strategy works for academic writing. Carefully review how academic writers in your discipline begin and end their work.

Often, writing introductions and conclusions is one of the most challenging parts of writing a composition. These parts of the text do a lot of heavy lifting as the reader’s first and last impression, and writing a strong introduction and conclusion requires careful planning and thinking. For this reason, we often advise writers to save these pieces for the end of the drafting process. It can be easier to write them when you know what your text says. However, some writers find it helpful to write an introduction as a frame that helps keep them on track as they write.

Whether you write your introduction first or last or somewhere in the middle of the process, you will need to consider how your introduction and conclusion work together to provide a smooth and satisfying journey for your reader. In the following sections, we will review some of the common strategies for developing strong introductions and conclusions.

Writing Strong Introductions

Picture your introduction as a storefront window: You have a certain amount of space to attract your customers (readers) to your goods (subject) and bring them inside your store (discussion).

Once you have enticed them with something intriguing, you then point them in a specific direction and try to make the sale (convince them to accept your thesis or statement of intent).

Your introduction is an invitation to your readers to consider what you have to say and then to follow your train of thought as you expand upon your thesis or statement of intent.

An introduction serves the following purposes:

- It establishes your voice and tone, or your attitude, toward the subject

- It introduces the general topic of the composition

- It states your thesis or your intention that will be supported in the body paragraphs

First impressions are crucial and can leave lasting effects in your reader’s mind, which is why the introduction is so important to any text. If your introductory paragraph is dull or disjointed, your reader probably will not have much interest in continuing with the text.

The Funnel Technique for Introductions

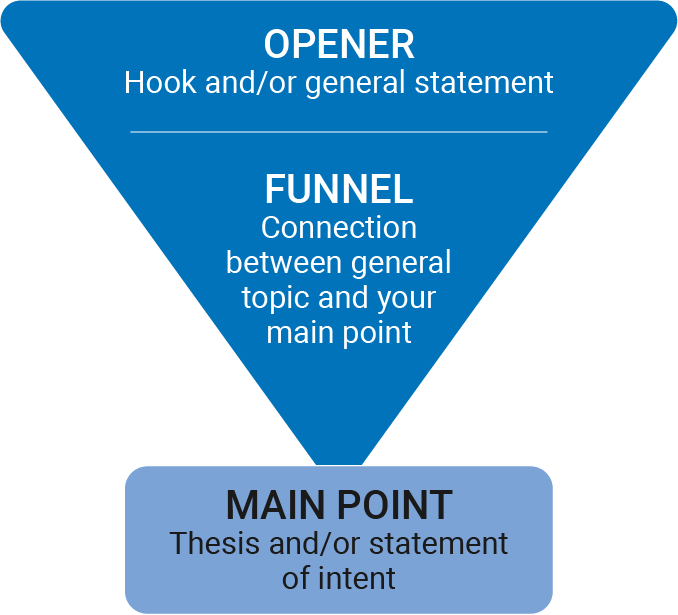

Your introduction should establish a shared context between you and your reader. Compositions often start with a hook that grabs the reader’s attention. In academic writing, the first sentences also set up the general context for the text. Once you have captured the reader’s attention and set up the topic for your text, add more details about your topic by stating general facts or ideas about the subject. As you move deeper into your introduction, you gradually narrow the focus, moving closer to your thesis or your statement of intention. Moving smoothly and logically from your introductory remarks to your thesis statement or statement of intent can be achieved using a funnel technique, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Remember that as your texts get longer, so too will your introductions. You may need to split your introduction into multiple paragraphs to help the reader find your meaning more easily.

In the following sections, we will examine each part of the funnel technique more closely.

The opener

Your introduction should begin with a hook that captures your readers’ interest and establishes the general topic of the composition.

Immediately capturing your readers’ interest increases the likelihood that they will read what you are about to discuss. You can garner curiosity for your composition in a number of ways. Try to get your readers personally involved by doing any of the following:

- Appealing to their emotions

- Using logic

- Beginning with a provocative question or opinion

- Opening with a startling statistic or surprising fact

- Raising a question or a series of questions

- Presenting an explanation or rationalization for your essay

- Opening with a relevant quotation or incident

- Opening with a striking image

- Including a personal anecdote

Here are some examples of strong openers in academic papers:

“Every time a student sits down to write for us, he has to invent the university for the occasion–invent the university, that is, or a branch of it, like History or Anthropology or Economics or English.” (Bartholomae, 1986)

This opening sentence introduces the provocative opinion that when we ask students to write academic essays in their first year of university, they have to “invent the university” because it is impossible for them to know what the university is at this point.

“Cultural critic Stanley Fish come talkin bout—in his three-piece New York Times “What Should Colleges Teach?” suit—there only one way to speak and write to get ahead in the world, that writin teachers should “clear [they] mind of the orthodoxies that have taken hold in the composition world” (“Part 3”). (Young, 2010)

From this opening sentence, the reader immediately knows that something interesting is going to happen in this essay. The sentence is written using African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), a dialect of American English. AAVE is juxtaposed with a quote from a white cultural critic, a juxtaposition that immediately captures our attention.

“We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribose nucleic acid (D.N.A.). This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest.” (Watson & Crick, 1953)

This opener is wonderful in its directness and understated approach. Watson and Crick are announcing one of the most important scientific discoveries ever: the discovery of the structure of DNA, and yet they do not shout their discovery from the rooftops. This understated approach catches our attention in the same way that a speaker who lowers their voice does.

The funnel

Before you tell your reader the main point of your composition, you have to give them more information about your topic. Typically, you set up your main point by moving from a general statement about your topic to your more specific main point. Each sentence in the funnel structure is more specific and leads the reader more closely to your focus.

Here’s an example of the funnel structure in an introductory paragraph:

[Opener] Many decisions are based on beliefs concerning the likelihood of uncertain events such as the outcome of an election, the guilt of a defendant, or the future value of the dollar. [Funnel] These beliefs are usually expressed in statements such as “I think that…,” “chances are…,” “it is unlikely that…,” and so forth. Occasionally, beliefs concerning uncertain events are expressed in numerical form as odds or subjective probabilities. What determines such beliefs? How do people assess the probability of an uncertain event or the value of an uncertain quantity? [Main point] This article shows that people rely on a limited number of heuristic principles, which reduce the complex tasks of assessing probabilities and predicting values to simpler judgmental operations. In general, these heuristics are quite useful, but sometimes they lead to severe and systematic errors. (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974, p. 1124)

Notice how the authors move the reader from a general statement about the topic to the narrow focus of their paper in four sentences:

- These beliefs are usually expressed in statements such as “I think that…,” “chances are…,” “it is unlikely that…,” and so forth.

- Occasionally, beliefs concerning uncertain events are expressed in numerical form as odds or subjective probabilities.

- What determines such beliefs?

- How do people assess the probability of an uncertain event or the value of an uncertain quantity?

The final two sentences of the funnel are questions, which help to set up the authors’ intention to answer these questions in the body of their paper.

The main point

Introductory paragraphs using the funnel technique typically end with a statement of the author’s main point. How the author frames and expresses their main point depends on the audience for the paper and the discipline in which they are writing.

In high school, you likely learned that you should end your introductory paragraph with a thesis statement, or a strong argumentative claim about a topic. Humanities disciplines often use this strategy in their academic writing. However, many academic writers use a different approach to setting up their main point at the end of an introductory paragraph; they state what they intend to explore in their text without making a strong argumentative claim.

Let’s look at examples of how three authors introduce the main point of their texts.

Example 1

Thematic analysis is a poorly demarcated and rarely acknowledged, yet widely used qualitative analytic method (Boyatzis, 1998; Roulston, 2001) within and beyond psychology. In this paper, we aim to fill what we, as researchers and teachers in qualitative psychology, have experienced as a current gap – the absence of a paper which adequately outlines the theory, application and evaluation of thematic analysis, and one which does so in a way accessible to students and those not particularly familiar with qualitative research. That is, we aim to write a paper that will be useful as both a teaching and research tool in qualitative psychology. Therefore, in this paper we discuss theory and method for thematic analysis, and clarify the similarities and differences between different approaches that share features in common with a thematic approach. (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 77)

Example 2

Example 3

In the first two examples, the authors end their introductions with a clear statement of what will happen in their texts. In the third example, the author ends their introductory paragraph with a sentence that states their position on the topic; this example is much more closely related to the traditional idea of a thesis statement than the first two examples.

These examples illustrate the importance of adhering to conventions in various disciplines, as they may vary significantly.

Writing Strong Conclusions

It is not unusual to want to rush when you approach your conclusion, and even experienced writers may falter in this last stage of drafting. But what good writers remember is that it is vital to put just as much attention into the conclusion as into the rest of the essay. After all, a hasty ending can undermine an otherwise strong essay.

A conclusion that does not correspond to the rest of your essay, has loose ends, or is unorganized can unsettle your readers and raise doubts about the entire essay. However, if you have worked hard to write the introduction and body, your conclusion can often be the most logical part to compose.

Common moves in strong conclusions

In academic writing, a strong conclusion may use several key strategies:

- A summary of the composition’s main points and argument

- An acknowledgement of the limitations of the research or ideas

- An exploration of the broader implications of the ideas in the text. The implications section of a conclusion is often structured from specific to general, with the broadest implications stated last.

- A final emphatic statement that leaves the reader with closure

Conclusions tend to be less rigidly structured than introductory paragraphs in academic writing, and writers will use a combination of these strategies. Let’s look at the conclusions that match the introductory paragraphs above.

Example 1

[Summary] Finally, it is worth noting that thematic analysis currently has no particular kudos as an analytic method / this, we argue, stems from the very fact that it is poorly demarcated and claimed, yet widely used. [Implications] This means that thematic analysis is frequently, or appears to be, what is simply carried out by someone without the knowledge or skills to perform a supposedly more sophisticated / certainly more kudos-bearing / ‘branded’ form of analysis like grounded theory, IPA or DA. We hope this paper will change this view as, we argue, a rigorous thematic approach can produce an insightful analysis that answers particular research questions. What is important is choosing a method that is appropriate to your research question, rather than falling victim to ‘methodolatry’, where you are committed to method rather than topic/content or research questions (Holloway and Todres, 2003). Indeed, your method of analysis should be driven by both your research question and your broader theoretical assumptions. [Emphatic statement] As we have demonstrated, thematic analysis is a flexible approach that can be used across a range of epistemologies and research questions. (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 97)

In this conclusion, the authors spend several sentences exploring the implications of their paper. Note how each sentence in the implications section widens the scope of discussion. Ultimately, the authors frame their exploration of the method of thematic analysis within the larger context of the role that methodology plays in research.

It is interesting to note that the authors were correct about the importance of this method to the field of psychology–it is one of the most cited papers ever.

Example 2

[Summary] We have developed an explanatory document to increase the usefulness of PRISMA. For each checklist item, this document contains an example of good reporting, a rationale for its inclusion, and supporting evidence, including references, whenever possible. [Implications] We believe this document will also serve as a useful resource for those teaching systematic review methodology. We encourage journals to include reference to the explanatory document in their instructions to authors.[Limitations] Like any evidence based endeavour, PRISMA is a living document. [Emphatic statement] To this end we invite readers to comment on the revised version, particularly the new checklist and flow diagram, through the PRISMA website. We will use such information to inform PRISMA’s continued development. (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff & Altman, 2009, para. 21-2)

In this brief conclusion, the authors summarize the main point of their text. They follow the summary with two sentences that detail the implications of their work. Next, they explain that their work will have to be continually updated, and they invite readers to help inform PRISMA’s future development.

Example 3

[Summary] The theoretical relationships between discourse and audience are complex and paradoxical, but [Implications] the practical morals are simple:(1) Seek ways to heighten both the public and private dimensions of writing. (For activities, see the previous section.)

(2) When working on important audience-directed writing, we must try to emphasize audience awareness sometimes. A useful rule of thumb is to start by putting the readers in mind and carry on as long as things go well. If difficulties arise, try putting readers out of mind and write either to no audience, to self, or to an inviting audience. Finally, always revise with readers in mind. (Here’s another occasion when orthodox advice about writing is wrong, but turns out right if applied to revising.)

(3) Seek ways to heighten awareness of one’s writing process (through process writing and discussion) to get better at taking control and deciding when to keep readers in mind and when to ignore them. Learn to discriminate factors like these:

(a) The writing task. Is this piece of writing really for an audience? More often than we realize, it is not. It is a draft that only we will see, though the final version will be for an audience; or exploratory writing for figuring something out; or some kind of personal private writing meant only for ourselves.

(b) Actual readers. When we put them in mind, are we helped or hindered?

(c) One’s own temperament. Am I the sort of person who tends to think of what to say and how to say it when I keep readers in mind? Or someone (as I am) who needs long stretches of forgetting all about readers?

(d) Has some powerful “audience-in-the-head” tricked me into talking to it when I’m really trying to talk to someone else–distorting new business into old business? (I may be an inviting teacher-audience to my students, but they may not be able to pick up a pen without falling under the spell of a former, intimidating teacher.)

(e) Is double audience getting in my way? When I write a memo or report, I probably have to suit it not only to my “target audience” but also to some colleagues or supervisor. When I write something for publication, it must be right for readers, but it won’t be published unless it is also right for the editors–and if it’s a book it won’t be much read unless it’s right for reviewers. Children’s stories won’t be bought unless they are right for editors and reviewers and parents. We often tell students to write to a particular “real-life” audience–or to peers in the class–but of course they are also writing for us as graders. (This problem is more common as more teachers get interested in audience and suggest “second” audiences.)

(f) Is teacher-audience getting in the way of my students’ writing? As teachers we must often read in an odd fashion: in stacks of 25 or 50 pieces all on the same topic; on topics we know better than the writer; not for pleasure or learning but to grade or find problems (see Elbow, Writing with Power 216-36).

[Emphatic statement] To list all these audience pitfalls is to show again the need for thinking about audience needs–yet also the need for vacations from readers to think in peace. (Elbow, 1987, pp. 66-7)

This lengthy conclusion focuses heavily on the implications of the author’s argument. There is a brief summary phrase (not even a full sentence), followed by a numbered list of practical implications designed to help writers and teachers of writing consider how thinking about the audience too much can impede a writer. Finally, the author ends on an emphatic statement.

From these examples, you can see that the structure of a conclusion often varies more than the structure of an introductory paragraph, but that some common moves are helpful for writers to master.

It is also important to note that there are a few moves that are generally frowned upon in conclusions. It is wise to avoid introducing new materials in a conclusion, as this has an unsettling effect on your reader. When you raise new points, you make your reader want more information, which you could not possibly provide in the limited space of your final paragraph. You should also avoid contradicting your main point in the conclusion. You may want to indicate that there are limitations to your ideas, but you don’t want to undermine your main point.

References

Bartholomae, D. (1986). Inventing the university. Journal of Basic Writing, 5(1), 4-23. https://doi.org/10.37514/JBW-J.1986.5.1.02

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Elbow, P. (1987). Closing my eyes as I speak: An argument for ignoring audience. College English, 49(1), 50-69. https://doi.org/10.2307/377789

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj, 339. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Tversky, A., Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Watson, J. D., & Crick, F. H. C. (1953). Molecular structure of nucleic acids: A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature, 171(4356), 737–738. https://doi.org/10.1038/171737a0

Young, V. A. (2010). Should writers use they own English?. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(1), 110-117.

Attributions

“Writing Strong Introductions and Conclusions” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted from: