Section 5: Important Moves in Academic Writing

Writing Arguments in the Disciplines

Introduction

In “Academic Writing as Persuasion,” you learned about Aristotle’s three rhetorical appeals and Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation. These two views of argumentation provide a solid foundation for understanding how persuasion differs in different disciplines. As you advance in your university studies, you will need to pay attention to what your discipline considers solid evidence in an argument and how arguments are best structured for that audience.

Evidence in Disciplinary Arguments

Academic disciplinary areas think differently about how humans can learn about and know the world around them. For instance, science disciplines assume that reality exists independently of human perception and that we can measure and evaluate this reality. On the other hand, the humanities and many social sciences argue that reality is socially constructed and that knowledge must be interpreted from the perspective of the humans involved. These different perspectives mean that the disciplinary areas will assess and evaluate the evidence used in arguments according to their foundational understanding of knowledge making.

Evidence in the humanities

Humanities disciplines use evidence to interpret meaning, trace historical developments, or construct philosophical arguments. Typical evidence in humanities arguments includes textual artifacts such as literary, professional, or historical documents. Humanities scholars value the close reading of texts, and arguments will typically use primary and secondary evidence to support a main claim. When humanities scholars evaluate an argument, they look at its coherence (do all of the elements of the argument work together?) and its fidelity to the source documents (has the author successfully interpreted the textual evidence?).

Evidence in the sciences

To persuade audiences in the science disciplines, writers typically use empirical, observable evidence from experiments and quantitative measurements. In other words, numerical evidence is prioritized in science disciplines, and scientists will often use figures and tables in addition to detailed descriptions of methodology and findings to persuade their readers of the value of their research. Scientists have precise standards for evidence that are often related to statistical analysis to determine if observations are patterned and not random. The science disciplines also value replicability, which means that they view evidence or research findings as more valuable if two different scientists can repeat an experiment or analyze a dataset and find the same result. While you will not be asked to meet these high standards of evidence as an undergraduate scientist, you should learn and pay close attention to how your discipline evaluates different types of evidence.

Evidence in the social sciences

The social sciences employ a more varied approach to evidence than the humanities and the sciences, and each subdiscipline in this area may have its own approach. There may even be differences within a subdiscipline. Despite these different approaches, the social sciences all share the common goal of understanding and exploring patterns in human behaviour, with the hope of explaining or predicting particular outcomes.

Typically, the social sciences employ a combination of quantitative techniques, such as surveys, statistics, and experiments, alongside qualitative methods, including interviews and case studies. Social scientists who use quantitative methods will evaluate evidence in much the same way as scientists. Those who use qualitative methods will value the credibility, coherence, and depth of a researcher’s interpretation.

Argument Structure

The different understanding of knowledge also impacts how disciplines may structure their arguments. When you are building an argument for a disciplinary audience, it is essential to review examples of successful arguments in that discipline. Pay close attention to the structure of the argument and where the writer places their central claim or main point. According to Heather Graves, Professor Emerita at the University of Alberta, some disciplines employ a direct argument structure, where the main claim is presented at the beginning of the argument. In contrast, others will use an indirect argument structure in which evidence is discussed and developed before the main claim is stated. These different argument structures are discussed in more detail below.

Direct argument structure

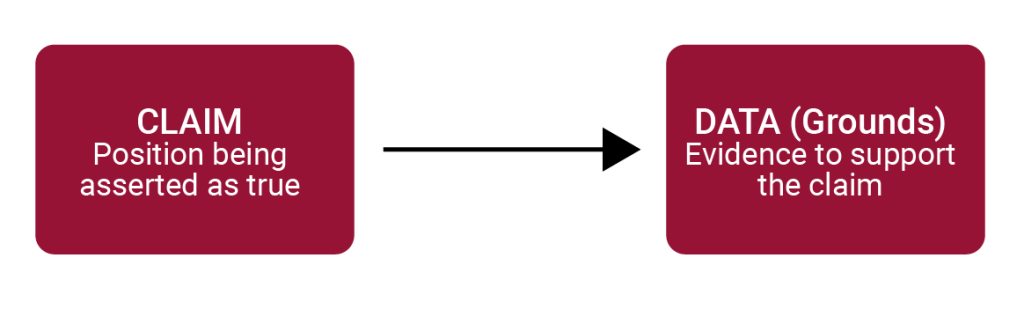

Writers using a direct argument structure will state their main claim early in their text, typically at the end of the introduction. A five-paragraph essay is an example of this “point-first” argument structure. After introducing their main claim, the author will provide reasons and evidence to support it. Each part of the argument builds on the previous evidence. Figure 1 shows the direct argument structure.

Direct arguments are often used to highlight a gap or deficiency in current research, propose a new interpretation of a text or phenomenon, or offer a critical evaluation of an idea. This structure foregrounds the author’s interpretation, making their position unmistakable. It is most often employed in disciplines such as literary studies, philosophy, and certain social sciences.

Indirect argument structure

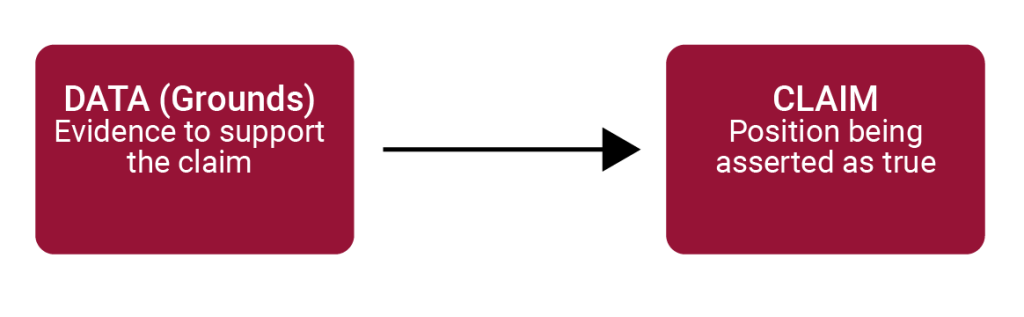

In an Indirect argument structure, the central claim of the argument is presented at the end. This “point-last” structure builds evidence for the claim carefully and methodically, often over several paragraphs. The grounds or evidence for a claim are typically embedded in procedural explanations and analyses of results. This allows the reader to follow the author’s chain of reasoning. It also invites readers to draw their own conclusions, as the writer downplays their position. Figure 2 shows the indirect argument structure.

Indirect argument structures are common in sciences and technical writing, as this structure allows the writer to explore complex phenomena rather than overtly trying to persuade readers from the outset of a text. This style of argument reflects the process of discovery typical in scientific disciplines, and it helps convey objectivity and credibility for logic-oriented audiences.

References

Graves, H. (2016). Principles of Argument: Part 1. Direct Persuasion. [PowerPoint slides]. University of Alberta.

Graves, H. (2016). Principles of Argument: Part 2. Indirect Argument. [PowerPoint slides]. University of Alberta.

Attributions

“Writing Arguments in the Disciplines” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.