Section 1: Why Do We Write?

Using Generative AI Responsibly

Questions about the relationship between humans and computers will shape your lifetimes. In the age of Generative AI, humans need to ask themselves:

- What is the value of human thinking and writing?

- What is the value of learning skills that Generative AI can reasonably do for us?

- What are the environmental and learning costs of using Generative AI?

- How can we use Generative AI to improve human conditions?

- How can we use Generative AI to make ourselves better thinkers and writers?

When you use Generative AI, think about the big picture:

Are you using it to help improve your thinking and writing, or are you using it to replace hard work that has value for you as a human?

You must also consider the following ethical issues when you use Generative AI.

Learning Loss

You have chosen to pursue a university degree to learn more about the world. What happens if you don’t do that learning? What happens if today’s students use Generative AI to complete their work and do the learning for them? What are the potential consequences for the future?

Academic researchers are working hard to understand how students can use Generative AI without losing meaningful learning. This is a developing area of research, so we don’t have all the answers yet. However, some common themes are emerging from research about the impacts of using Generative AI for writing tasks.

Generally, using Generative AI may have value if you use it specifically to advance your learning. Here are some recent findings that indicate that this might be the case:

- There may be value in using Generative AI as a personalized learning tool to help you improve your critical thinking, but you need to use it cautiously to avoid learning loss (Adewumi et al.. 2023; Hostetter et al., 2024; Lehmann, Cornelius, & Sting, 2024; Stadler, Bannert, & Sailer, 2024)

- Using Generative AI for summarizing may help you better understand the material you are learning (Ju, 2023).

- Generative AI tools like Grammarly may provide helpful feedback on your writing, but it is best to get human feedback in addition to Generative AI feedback (Escalante, Pack & Barrett, 2023).

However, students need to be very careful to avoid learning loss when they use Generative AI tools.

- Overuse of Generative AI for writing may result in a loss of accuracy in your writing and may impede your development as a critical thinker and member of the academic community (Anson, 2024; Ju, 2023).

- You may face difficulties maintaining your own voice as a writer if you introduce AI-produced or AI-enhanced writing into your texts (Wang, 2024).

- You may not spend the necessary time revising if you use AI-generated texts. (Radtke & Rummel, 2025). As revision is the stage of writing when you deepen your critical thinking, you are likely missing out on important learning.

Remember that our understanding of the impact of using Generative AI for writing is still emerging. The findings of these studies are just the beginning of our investigations into this issue.

If you do use Generative AI for writing, pay attention to why and when you use it. Are you using it to avoid some of the hard work of writing? Is that hard work essential to your learning? Your instructors can’t make all these decisions for you, so you must be responsible for your learning and potential learning loss.

Academic Integrity

When you stand on the stage to receive your university degree, you want that degree to mean something. It should reflect your hard work and your learning. It should show the world that your studies are meaningful and will help you contribute to society.

What if you find out that the person standing next to you on the stage used Generative AI to complete some of their work for their degree? What if employers find out that many university students have done so? What if you find out your doctors, lawyers, professors, and community leaders used Generative AI to get their university degrees? Would you feel confident in these people’s ability to help you?

To maintain the value of your university degree, we must uphold academic integrity. Generative AI is a complex issue with respect to academic integrity because different disciplines have different relationships to this technology. Your computing science instructor may encourage you to explore this technology for coding, but your English instructor may not want you to use it at all. This means that you will likely encounter different policies concerning the use of Generative AI while at university.

You are responsible for understanding your university’s and your instructor’s policies regarding using Generative AI in your coursework. This isn’t just about preventing cheating; it is also about preserving the value of your hard-won university degree.

Lost of Human Connection

Writing is ultimately about connecting with other human beings. One of the reasons that Generative AI writing is often detectable is that it fails to consider the nuances of particular rhetorical situations. In other words, it does not adapt its writing to the relationship between the writer and the reader in that particular time and place.

We are not likely to react positively when we discover that Generative AI has written something we have read.

Consider how you would respond to these questions:

- How would you feel if you discovered this textbook was written by Generative AI?

- How would you feel if your instructors graded your papers with Generative AI?

- How would you feel if you found out your favourite TV show was written by Generative AI?

Chances are you reacted negatively to some of these ideas. This is because there is a social relationship embedded in writing. If we discover we are interacting with a machine rather than a human, this interaction feels inauthentic and disappointing. We are social creatures, and we thrive through authentic interaction and connection with each other.

Hallucinations

When Generative AI provides us with inaccurate information, we call this a hallucination. Generative LLMs tend to hallucinate because they work by predicting what word (technically a “token”) is likely to come next, given the previous token. They operate by probability. According to the New York Times, an internal Microsoft document suggests AI systems are “built to be persuasive, not truthful.” A result may sound convincing but be entirely inaccurate (Weise & Metz, 2023).

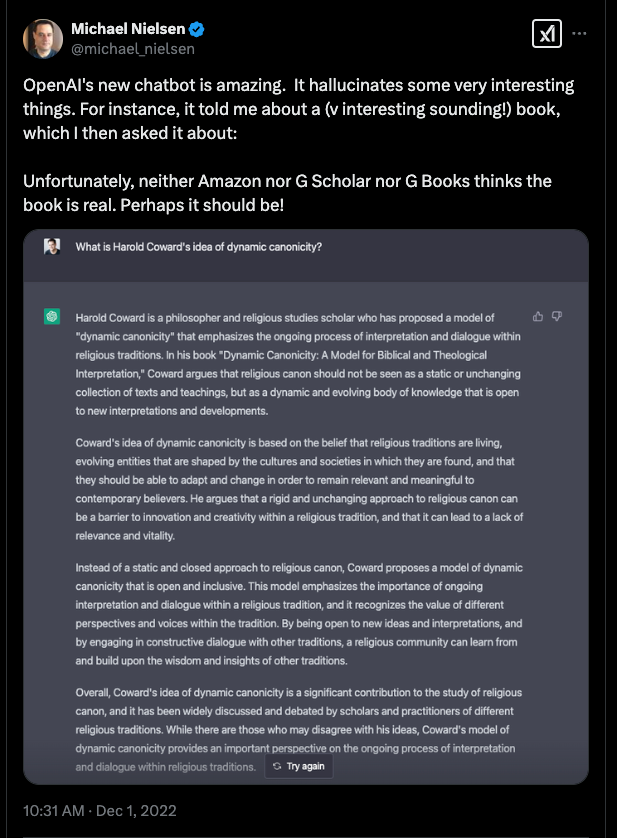

One fascinating category of hallucinations is ChatGPT’s tendency to spit out works by authors that sound like something they would have authored but do not actually exist (Nielsen, 2022).

Developers of AI models have been working hard to improve the accuracy of their output. Newer models may provide more accurate results.

Biases

Although Generative AI output may seem neutral and objective, it carries biases inherited from its human creators. These biases are introduced primarily through the data selection to train the AI models and the Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

Humans are responsible for selecting the data used to train Generative AI models. Invariably, this data comes from a subset of texts and images available on the Internet, and developers must choose what to include and exclude in the training database. Similarly, human judgment is used to fine-tune Generative AI output. In this way, Generative AI is susceptible to all of the same biases and stereotypes as human beings.

You should be aware of these biases when you use Generative AI tools.

Gender biases

In “Introduction to Generative AI and Writing,” you saw how tokenization and attention mechanisms can lead to gender bias in an LLM’s output. Academic research confirms that Generative AI has inherited explicit and implicit gender biases. For instance, Yixin Wan and her co-authors (2023) found significant gender stereotypes in AI-generated reference letters. In addition, recent studies have shown gender stereotypes replicated in the output of AI image generators (Sun et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2024).

Racial biases

Political biases

Shortly after ChatGPT launched in November 2022, users noticed that its filter seemed to have political and other biases. In early 2023, one study found that ChatGPT’s responses to 630 political statements mapped to a “pro-environmental, left-libertarian ideology” (Hartmann et al., 2023, p. 1). Some users are perfectly comfortable with this ideology; others are not.When the Brookings Institution conducted its own evaluation in May 2023, they again found that ChatGPT veered consistently left on specific issues. The report’s explanation was twofold:

The dataset for ChatGPT is inherently biased. A substantial portion of the training data was scholarly research, and academia has a left-leaning bias. RLHF by employees hand-picked by OpenAI may have led to institutional bias in the fine-tuning process. (Baum & Villasenor, 2023)

After receiving critical feedback on biases related to ChatGPT 3.5 outputs, OpenAI worked to improve the bias of its next model, GPT-4. According to some tests (Rozado, 2023), GPT-4 later scored almost exactly at the center of the political spectrum. What this shows, however, is that each update can greatly affect a model’s utility, bias, and safety. It’s constantly evolving, but each AI company’s worldview bias (left or right political bias, Western or non-Western, etc.) greatly shapes generated outputs.

Evidence of political bias should concern everyone across the political spectrum, particularly as technology leaders take on influential political roles.

Deepfakes

As Generative AI models improve at creating images and videos, creating fake material becomes easier. This will have serious consequences for humanity. Deepfakes can be used to support fake news stories, which have the potential to cause serious societal disruption. For instance, a deepfake video showing Ukrainian President Volodymr Zelenskyy telling soldiers to cease fighting was circulated in March 2022, shortly after the invasion of Ukraine by Russia (Milmo & Sauer, 2022). Had Zelenskyy not immediately countered with a real message, the fake message could have negatively affected the war in Ukraine.

Deepfakes undermine our trust in what we see and hear on the Internet, and they can be used in nefarious ways. We need to be very vigilant about fake news and deepfakes.

Copyright Violations

After the release of ChatGPT 3.0 in 2022, content creators like writers, visual artists, musicians, and actors became concerned that their materials and images were being used to train AI models without their permission and compensation. Since then, these artists have filed copyright lawsuits against companies that have built Generative AI models. Most of these lawsuits are still underway, and as a society, we will have to determine how to compensate human artists and creators properly for their work.

Privacy Risks

Be careful with what you share with Generative AI. If you share data with LLMs, it may become part of its training material. The models may inadvertently share your private or sensitive information with other users. It is always best to review the privacy policies of any Generative AI model before you use it.

Environmental Issues

Generative AI uses energy more intensively than other online tools that you use. According to a 2024 estimate by the International Energy Agency, the energy consumption from AI, data centres, and cryptocurrency will double by 2026. This is driving an increase in global electricity demand. This increase will impact our world’s ability to meet our carbon emission goals and address the threats of climate change and other environmental concerns.

Emergent Properties

Generative AI models and LLMs are complex systems that can behave in unexpected ways. Because these systems are so complex, even Generative AI developers can’t fully predict what these tools will do. This uncertainty is concerning, and we will have to keep a close eye on this in the future (Woodside, 2024).

Additional Resources

The University of Alberta Library offers a micro-course on the Pros and Cons of Generative AI.

Wired Media maintains a list of AI Copyright Lawsuits in the US.

MIT News’ article “Explained: Generative AI’s environmental impact” offers a clear explanation of how the use of Generative AI impacts energy demand and water consumption.

References

Adewumi, T.P., Alkhaled, L., Buck, C., Hernandez, S., Brilioth, S., Kekung, M.O., Ragimov, Y., & Barney, E. (2023). ProCoT: Stimulating critical thinking and writing of students through engagement with Large Language Models (LLMs). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.09801

An, H., Acquaye, C., Wang, C., Li, Z., & Rudinger, R. (2024). Do Large Language Models discriminate in hiring decisions on the basis of race, ethnicity, and gender? arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.10486

Anson, D. W. J. (2024). The impact of large language models on university students’ literacy development: a dialogue with Lea and Street’s academic literacies framework. Higher Education Research & Development, 43(7), 1465–1478. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2024.2332259

Baum, J., & Villasenor, J. (2023, May 8). The politics of AI: ChatGPT and political bias. Brookings; The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-politics-of-ai-chatgpt-and-political-bias/

Bowen III, D. E., Price, S. M., Stein, L. C., & Yang, K. (2024). Measuring and mitigating racial bias in large language model mortgage underwriting. Available at SSRN, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4812158

Escalante, J., Pack, A., & Barrett, A. (2023). AI-generated feedback on writing: Insights into efficacy and ENL student preference. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00425-2

Hartmann, J., Schwenzow, J., & Witte, M. (2023). The political ideology of conversational AI: Converging evidence on ChatGPT’s pro-environmental, left-libertarian orientation. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.01768

International Energy Agency. (2024). Electricity 2024. https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-2024

Ju, Q. (2023). Experimental evidence on negative impact of generative AI on scientific learning outcomes. Available at SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4567696

Lehmann, M., Cornelius, P.B., & Sting, F.J. (2024). AI Meets the Classroom: When Does ChatGPT Harm Learning? arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.09047

Milmo, D. & Sauer, P. (2022, March 19). Deepfakes v per-bunking: Is Russia losing the infowar?. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/19/russia-ukraine-infowar-deepfakes

Nielsen, M. @michael_nielsen. (2022, December 1). The most important thing about AI alignment is not what we believe now, but how we respond as new evidence emerges [Tweet]. X (formerly Twitter). https://x.com/michael_nielsen/status/1598369104166981632

Poulain, R., Fayyaz, H., & Beheshti, R. (2024). Bias patterns in the application of llms for clinical decision support: A comprehensive study. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.15149

Radtke, A., & Rummel, N. (2025). Generative AI in academic writing: Does information on authorship impact learners’ revision behavior? Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100350

Rozado, D. (2023, March 28). The political biases of Google Bard [Substack newsletter]. Rozado’s Visual Analytics. https://davidrozado.substack.com/p/the-political-biases-of-google-bard

Stadler, M., Bannert, M., & Sailer, M. (2024). Cognitive ease at a cost: LLMs reduce mental effort but compromise depth in student scientific inquiry. Computers in Human Behavior, 160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108386

Sun, L., Wei, M., Sun, Y., Suh, Y. J., Shen, L., & Yang, S. (2024). Smiling women pitching down: auditing representational and presentational gender biases in image-generative AI. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad045

Wan, Y., Pu, G., Sun, J., Garimella, A., Chang, K. W., & Peng, N. (2023). ” Kelly is a warm person, Joseph is a role model”: Gender biases in LLM-generated reference letters. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.09219

Wang, C. (2024). Exploring students’ generative AI-assisted writing processes: Perceptions and experiences from native and nonnative English speakers. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-024-09744-3

Weise, K., & Metz, C. (2023, May 1). When AI Chatbots hallucinate. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/01/business/ai-chatbots-hallucination.html

Zhou, M., Abhishek, V., Derdenger, T., Kim, J., & Srinivasan, K. (2024). Bias in generative AI. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.02726

Attributions

“Using Generative AI Responsibly” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted in part from the following source:

- “10 How Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT Work” by Joel Gladd, Write What Matters is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. This source was used for the sections on hallucinations and political bias.