Section 1: Why Do We Write?

Developing a Growth Mindset with Respect to Writing

One of the most common misconceptions about writing is that our writing abilities are fixed and constant. For instance, you might already have decided that you are a bad or a good writer based on feedback from one of your teachers or instructors in the past. However, having a set idea about who you are as a writer will likely impede your ability to develop better writing skills. Successful writers have what psychologist Carol Dweck (2006) calls a growth mindset – they believe that their abilities can improve with effort, learning, and persistence.

The need for a growth mindset with respect to writing is supported by research in writing studies. Nancy Sommers and Laura Saltz (2004), well-known writing studies scholars, conducted a study that analyzed the development of writing proficiency for 400 Harvard students over the course of their undergraduate degrees. The study found that students who embraced their status as novice academic writers were more likely to improve their writing skills over their four years at Harvard. What does this mean? It means that the students who recognized that they had a lot to learn about writing and embraced the challenge of university writing were more likely to improve their skills.

For example, Sommer and Saltz (2004) asked their subject participants what advice they would give first-year students about writing. One student responded, “See that there is a greater purpose in writing than completing an assignment. Try to get something and give something when you write” (p. 139). This student’s writing improved because they focused on the larger goals of learning and writing. They paid attention to the new context of writing at university rather than sticking to the ideas of writing that they had when they entered university. In other words, seeing your writing assignments as opportunities to practice learning rather than examples of a fixed set of writing abilities will improve your chances of becoming a better writer.

To develop a growth mindset, it is important to understand the differences between fixed and growth mindsets, how to rewrite the script in your head, and how to apply this to writing.

What are Fixed and Growth Mindsets?

Psychologist Carol Dweck (2006) distinguishes between fixed and growth mindsets. If you have a fixed mindset, you believe that your intelligence and abilities are constant and will never change. If you have a growth mindset, you think that you can improve your intelligence and skills through effort, learning, and persistence. Table 1 compares the key characteristics of fixed and growth mindsets.

| Fixed Mindset | Growth Mindset |

|---|---|

| Believes that intelligence and abilities are pre-determined and unchanging | Believes that intelligence and abilities can be improved over time |

| Avoids challenges due to fear of failure. Stays in the comfort zone. Views obstacles as permanent and insurmountable | Embraces challenges and see them as an opportunity for learning and growth. Views obstacles as challenges to be overcome |

| Undervalues the impact of effort and practice. May see the need for effort as a sign of weakness or inability. | Understands effort is necessary for improvement. Persists in the face of setbacks |

| Becomes defensive or dismissive when receiving feedback | Learns from feedback. Open to constructive criticism and use feedback to improve their work |

| Compares themselves to others. May be threatened by the success of others or may experience jealousy | Finds inspiration in others’ success |

| Focuses on outcomes. Places emphasis on performance | Focuses on process and learning |

Table 1. A comparison of fixed and growth mindset attitudes.

You may recognize some of the characteristics of a fixed mindset in your own attitudes, especially your attitudes about writing. Fear not! It is possible to change your outlook and adopt a growth mindset, even for a skill as complex and difficult as academic writing.

How Can You Adopt a Growth Mindset?

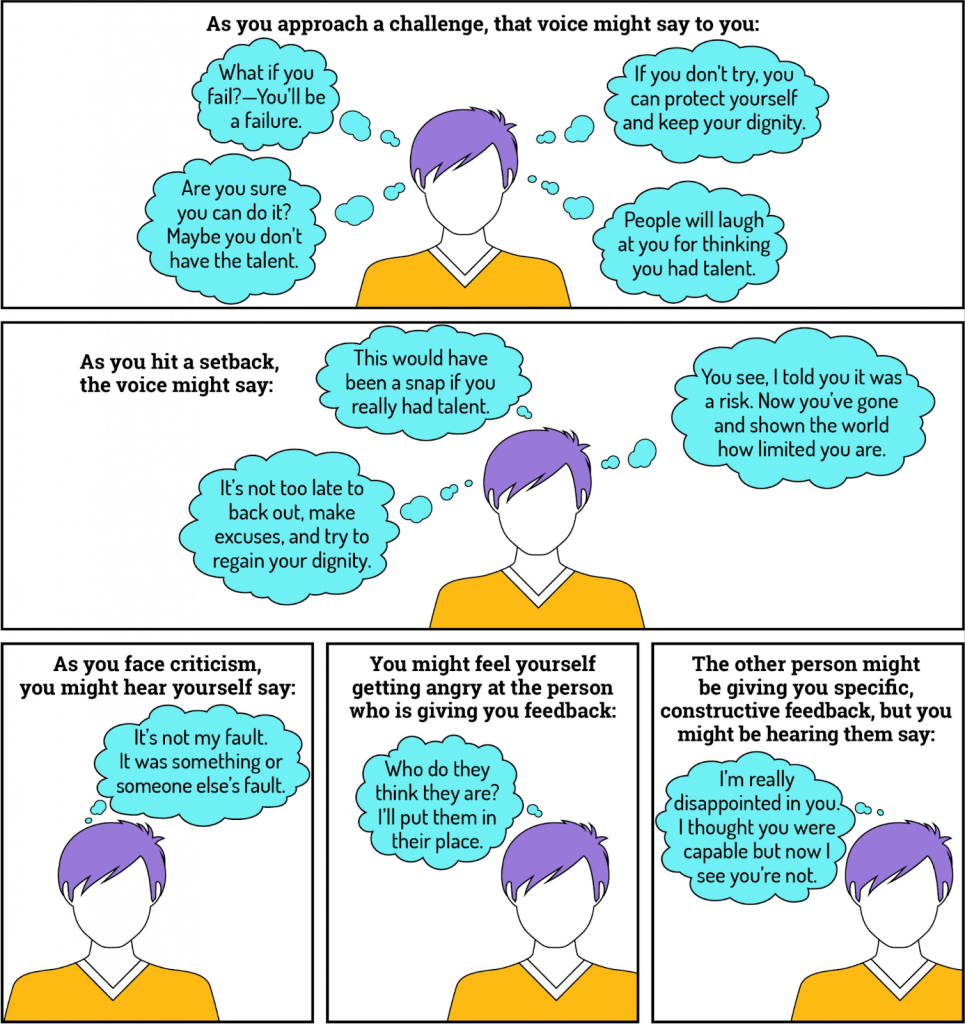

Step 1: Learn to hear your fixed mindset voice

To get the most out of the learning opportunities at university, you need to recognize when your own mindset might be getting in the way of your learning and use strategies to change it. Figure 1 shows you the fixed mindset thoughts you might hear in your head as you approach a challenge.

- I'm not good at this.

- This is too hard.

- I don't want to look stupid.

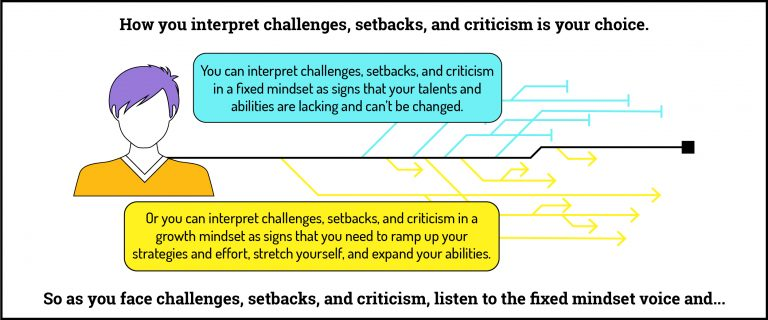

Step 2: Recognize that you have a choice

When you hear your own fixed mindset thoughts, you can gently remind yourself that you can decide to view your situation in a different way. Figure 2 shows you alternatives to interpreting challenges, setbacks and criticisms.

- Challenge: Instead of avoiding challenges, embrace them as opportunities to grow.

- Setbacks: View setbacks as temporary and part of the learning process.

- Criticism: See criticism as feedback that can help you improve.

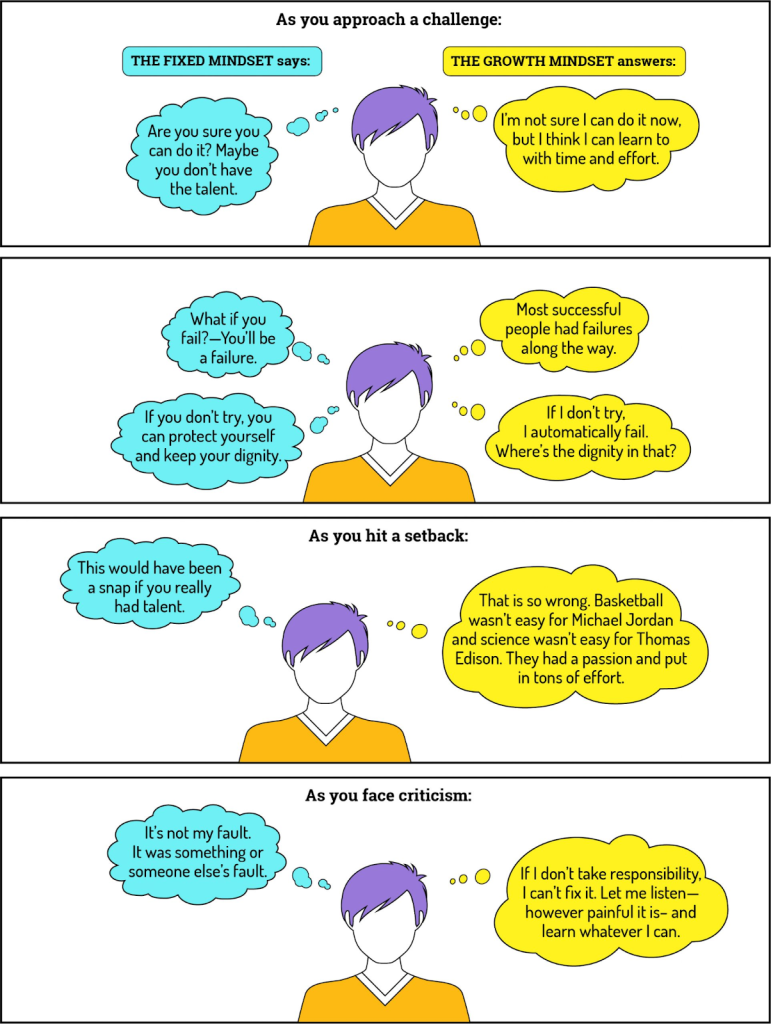

Step 3: Talk back with a growth mindset

Once you have recognized that you can change a fixed mindset thought, you should replace it with a growth mindset idea. Figure 3 shows you how you can talk back to your own limiting thoughts.

- Fixed Mindset: "I'm not good at this." Growth Mindset: "I can improve with practice."

- Fixed Mindset: "This is too hard." Growth Mindset: "I can break this down into smaller steps."

- Fixed Mindset: "I don't want to look stupid." Growth Mindset: "Mistakes are part of learning."

Step 4: Take the growth mindset action

With practice, you can learn to decide which voice you will listen to and act on. Ideally, you will:

- Take on the challenge wholeheartedly.

- Learn from your setbacks and try again.

- Hear the criticism and act on it.

How Can You Adopt a Growth Mindset with Respect to Writing?

Remember that writing expertise involves multiple types of knowledge

Sometimes, we think that writing well only involves writing correctly. We think we could be better writers if we only knew grammar better. While grammar is an integral part of writing well, many other competencies contribute to good writing, and we have to practice and work on all of these skills. Even if you struggle with one aspect of writing, there may be other aspects where you are strong. Understanding the complexities of writing and its various component skills can help you target your efforts to improve.

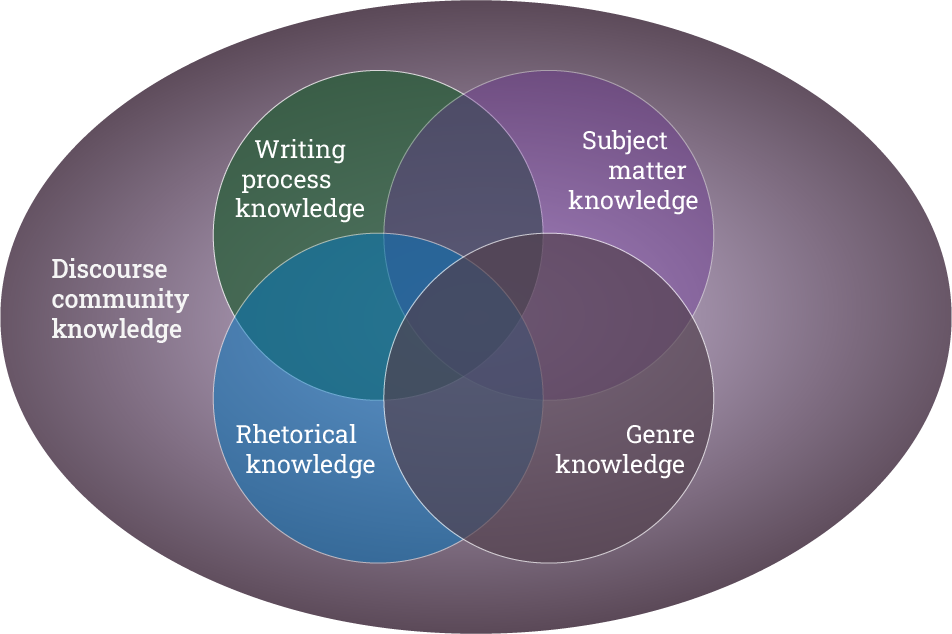

Have a look at the model of writing expertise by writing studies scholar Anne Beaufort (2004) in Figure 4. Beaufort (2007) identifies five knowledge domains that are necessary to become an expert writer (p. 19).

According to Beaufort’s model, you must understand and manage the writing process well and know your subject matter well to be an expert writer. You must also know the conventions and constraints of the genres you are writing (i.e., a type of text like an essay or a text message). This is where grammar comes into play. Usually, a genre will have some built-in expectations with respect to grammar. For example, your friends might make fun of you if you use too much punctuation in your text messages. However, your professors will likely penalize you for not using punctuation according to the rules of Standard Written English. The genre of the text message has different expectations with respect to correctness than the genre of the essay.

Expert writers also have good rhetorical knowledge. Rhetorical knowledge is understanding the relationship between the reader and the writer and the ability to cultivate this relationship through writing. This is a challenging aspect of writing, and it is one area where humans are far better than computers.

These competencies are set within the larger competency of discourse community knowledge. A discourse community is a group of people who work together towards a common goal. Whenever we write, we write within and for a community. Expert writers know and understand their discourse communities' needs, making their writing effective. This is also an area where Generative AI cannot compete with human writers.

Knowing that writing involves many different competencies can help you focus on specific areas for growth and development. Instead of thinking, “I am a bad writer,” reflect on all of these aspects of writing and formulate a plan to tackle specific challenges related to the different areas of writing competencies.

Focus on the journey

When we learn to write in school, we often also learn to tie our success as writers to the grade on our final product. However, this rarely tells the story of our learning on the way to that final product, and it never gives us a good measure of where we are at in our overall progress as writers. It is simply a measurement of your work on one piece of writing with one particular goal in one particular context.

Thinking about your writing journey will help you put your learning into perspective and help you concentrate on the big picture. For instance, say you realize that you don’t spend enough time on the revision stage of writing. You suspect that spending more time on revision might help to improve your grades. You could set this goal for your next writing assignment: I will write a draft, get feedback, and revise my assignment at least once before handing it in. This goal gives you a tangible and achievable way to measure your improvement. It might not immediately pay off in terms of grades, but it will likely teach something new about the writing process.

You might have already concluded, “I’m not good at writing.” Use a growth mindset to transform this statement to “I’m not good at writing yet.” Learning to write well is a life-long journey. The story of you as a writer does not end with a poor grade on a writing assignment. Take a deep breath, review some of the strategies for adopting a growth mindset, and see any challenges you face as important steps for learning.

To keep focused on the big picture, it is helpful to reflect on your writing progress at regular intervals. After you have completed a writing assignment, ask yourself what you thought went well and where you feel you could improve. Based on your assessment, set goals for your next writing assignment. Consider keeping a journal of your writing progress.

Remember that struggle is normal

It is normal to struggle as we learn, and it is especially normal to struggle as a writer. Even famous writers face bouts of uncertainty and difficulty. It is perfectly normal to doubt your own writing and to struggle to put your thoughts into words. If you get stuck, remember that you can always try an invention activity to get yourself going again.

Remember also that moments of struggle are tied to the discomfort of learning. If everything you are learning is easy, you are likely not learning at the right level. The best situation for learning is when you are challenged with tasks that are slightly beyond your capabilities. Learning should be a productive struggle where you develop better resilience and problem-solving skills. Struggling is part of the process of getting better.

Feedback, feedback, feedback

Feedback is one of the key elements to improving your writing. Seek out feedback and listen to it carefully. Ask for clarification if you don’t understand your instructor's feedback on your writing. You can learn more about feedback in the chapter “Providing and Receiving Feedback.”

Additional Resources

- Find out more about growth and fixed mindsets in John Spencer’s video “Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Mindset.”

- Singer John Legend describes the role of failure and effort in becoming successful in the video “John Legend: Success through effort.”

- Derek Sivers, a professional clown and musician, talks about why we need to make more mistakes in his TED talk “Why you need to fail.”

References

Beaufort, A. (2007). College writing and beyond: A new framework for university writing instruction. Utah State Press.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Sommers, N., & Laura Saltz. (2004). The novice as expert: Writing the freshman year. College Composition and Communication, 56(1), 124–149. https://doi.org/10.2307/4140684

Attributions

"Developing a Growth Mindset with Respect to Writing" by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted in part from the following source:

- "What is a mindset?" by Alison Flynn; Elizabeth Campbell Brown; Emily O'Connor; Ellyssa Walsh; Fergal O'Hagan; Gisèle Richard; and Kevin Roy, Growth & Goals (HSS2121- Winter 2021) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. This source was used for the section on how to adopt a growth mindset.