Section 2: The Writing Process

Revising

Revision is the process of re-seeing your draft. When we revise our texts, we ask ourselves and others how well our writing reflects our goals. We consider our text’s purpose, audience, and genre and make substantial changes to improve its effectiveness.

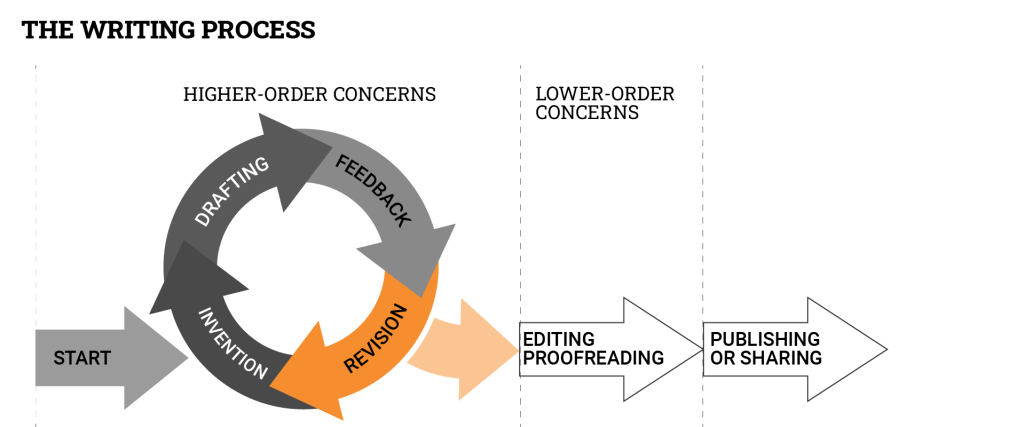

Revision is closely related to providing and receiving feedback, which you can learn more about in “Providing and Receiving Feedback”. We cannot revise effectively without considering our text from a reader’s perspective. Sometimes, we don’t have access to a test reader, so we must take on that role ourselves. Figure 1 shows you where revision typically occurs in the writing process.

Revision is often confused with editing and proofreading, but revision is more substantial than either of those activities. When you revise, you usually take apart and reassemble your text, which can look completely different at the end of this process. Expert writers will revise their text multiple times, moving through cycles of drafting, seeking feedback, and revising. Sometimes, your text will change dramatically as you revise. Once you are happy with the content of your text, you can move to editing and proofreading, which involve lower-order concerns like style, grammar, and citation.

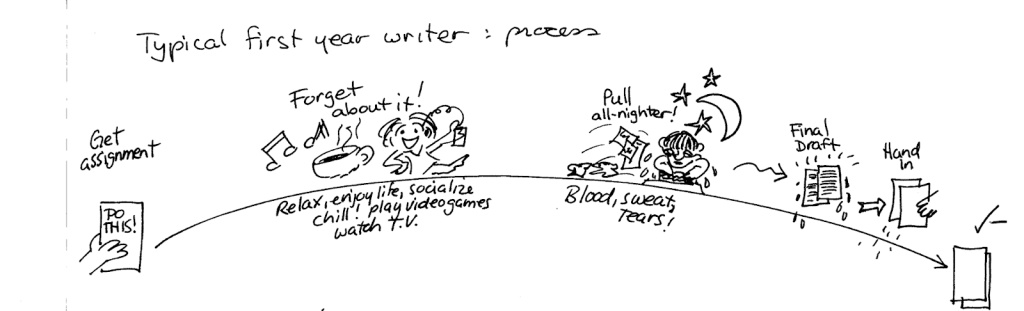

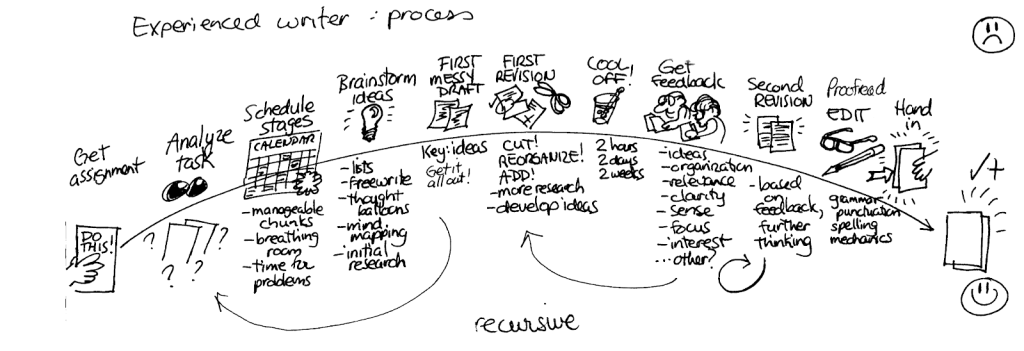

We know from writing studies research that novice writers do not revise as effectively as experienced writers (Sommers, 1980). In fact, many novice writers have never substantially revised their writing. Novice writers tend to write a draft, proofread it for surface errors like typos, and submit their drafts to their teachers or instructors. While this strategy may have worked for you in high school, university writing is more complex and requires strong critical thinking. Writing multiple drafts and seeking feedback allows you to improve the depth of your thinking, which will likely improve the effectiveness of your academic writing. Figures 2 and 3 compare novice and experienced writers’ writing processes. You can see the iterative and recursive nature of an experienced writer’s process compared to the linear nature of the novice writer’s process.

Note. From “Writing Processes” by Christina Grant, Writing across the University of Alberta, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Note. From “Writing Processes” by Christina Grant, Writing across the University of Alberta, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

As you can see, incorporating revision into your writing process will likely be one of the biggest changes you will make as a university student, especially with high-stakes writing assignments. You will need to build time into your writing plan for revision. As university writers, it is also important to recognize that the extent to which you can revise is linked to the time you have to complete a project. A semester-long project should include several rounds of revision; a timed essay on an exam will likely only include minor revisions.

What Does Revision Involve?

Revision involves evaluating the appropriateness and effectiveness of your content and its arrangement in your text from a reader’s perspective. Before you revise, you will likely gather feedback from readers, but sometimes, this isn’t possible. In this case, you must evaluate your text from an imaginary reader’s perspective.

The following activities are part of a typical revision process:

- Adding new material to help your reader better understand your text

- Deleting irrelevant information that distracts from your main point

- Rewriting material to improve clarity and focus

- Moving information to improve the flow of your text.

Remember that revision focuses on high-order concerns. We are not concerned with style or grammar because there is no point in fixing the style or grammar of sentences that could get deleted. Once we are satisfied with our content, we will get to these elements in the editing and proofreading stages.

When revising your texts, you can ask yourself the following guiding questions. You can also share these questions with test readers to help guide them in the feedback process.

Questions to guide revision

Questions about content

- Is the purpose of your text clear? Does the purpose match the assignment requirements?

- Does your draft have a strong central focus or thesis statement?

- Have you included all of the necessary elements for the reader?

- Have you answered the reader’s questions when they will arise?

- Have you included material that is not relevant to your purpose?

- Is your content factually correct? Are your sources credible, relevant, and connected to your argument?

- Is your argument sound? Do you provide evidence through examples or data to support your argument?

Questions about organization

- Is your content organized in a way that is typical to the genre? For example, if you are writing a lab report, did you order everything in the typical way of a lab report?

- Are your ideas organized logically?

- Are your paragraphs organized well? Do you focus on one idea in each paragraph?

- Are your sentences organized well?

Make a Revision Plan

Once you have gathered feedback on your draft, it is helpful to build a revision plan. Make a list of the revisions you need to make. Identify the importance of each revision. Typically, you will begin revising higher-order concerns such as content and argumentation. Then, you will move to issues of organization. Move from the most important revisions to the least important ones.

You may not want to incorporate all the feedback that you receive. Sometimes, you will receive feedback that you disagree with. You can reject that feedback, but be cautious: if it is your instructor or a person in power who has given you the feedback, you may suffer consequences for not following their advice.

Using Generative AI for Revision

Consider academic integrity

Please check with your instructor, course syllabus and your institution’s policies about using Generative AI before you use these tools to help you revise your text.

Use it effectively

Generative AI may be a helpful tool for revision. Once you revise your text, you can prompt an AI to evaluate your changes. For instance, you could prompt it as follows:

- I am revising a draft of a rhetorical analysis for a first-year university course. I received feedback that I did not include enough contextual information for the reader. Specifically, the feedback said that I did not adequately explain X point. Read my revision. Tell me if I have improved the contextual information for the reader in the following text. If I have not, provide me with suggestions on what I should include. Do not rewrite my text. [Attach your text]

Generative AI can create a reverse outline of your text to help you evaluate how effectively it is organized. A reverse outline is a helpful technique whereby you work paragraph by paragraph through a text and make a list of phrases or sentences that indicate what each paragraph is about. This list is a reverse outline, and you can use it to evaluate the overall organization of your text and the organization within each paragraph. You can prompt Generative AI to create a reverse outline for you as follows:

- Please create a reverse outline of the following text. Based on the reverse outline, evaluate the logical flow of the text in general and the flow of information within paragraphs. Provide suggestions on how to improve the flow of the text. Identify sentences that do not belong in a paragraph. Do not rewrite my text. [Attach your text]

Beware of the limitations

- Generative AI will teach you to write in a homogenized way. It looks for common patterns in texts, and it will advise you on ways to ensure that your text follows those patterns. Ultimately, this could lead to uninspired and dull writing. This might not be what you want.

- Generative AI might not recognize aspects of your writing that are specific to your context. For instance, your instructor or editor may have very particular things they expect in your text, and Generative AI may not understand how to handle these expectations.

Consider your learning journey

Learning to revise is an essential part of becoming a better writer. Revision is about better communicating with your readers, and generally, Generative AI cannot mimic the rhetorical knowledge of a human writer. In other words, Generative AI has difficulties understanding the nuances of the relationship between the writer and their readers, which often shows in its output.

Consider ethics

- Remember that when you share your writing with Generative AI, it may be added to the tool’s learning database. It may be used in future responses to other users. Do not disclose any private information.

- Consider the ethical implications of using these tools. Make sure you acknowledge your use of Generative AI in the acknowledgements section of your work.

Additional Resources

Arizona State’s Study Hall program has a helpful video on revision called “The Writing Process: Revision.”

American author Obert Skye discusses revision in his Ted Talk “The Magic Of Revision.”

Different professionals describe their revision processes in the video “The Writer’s Guide: Revision” by Soomo.

References

Sommers, N. (1980). Revision strategies of student writers and experienced adult writers. College Composition & Communication, 31(4), 378-388. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc198015930

Attributions

“Revising” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Figures 2 & 3 are from “Writing Processes” by Christina Grant, Writing across the University of Alberta is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0