Section 5: Important Moves in Academic Writing

Mastering Stance and Engagement in Academic Writing

Until recently, academic writing, especially in science and related disciplines, was generally assumed to be an impersonal and objective presentation of facts. This assumption has begun to fade gradually, thanks to studies in rhetorical structure and the linguistic features of academic texts.

Indeed, writing studies during the last three decades have established that academic writers and readers interact through written texts. When writers construct a persuasive argument for establishing their knowledge claims on a topic, they should offer a credible representation of themselves and their research. Hyland (2005) argues that writers seek to achieve this “by claiming solidarity with readers, evaluating their material and acknowledging alternative views, so that controlling the level of personality in a text becomes central to building a convincing argument” (p. 173). Writers need to conceive of writing as ‘dialogic’ (Bakhtin, 1986) and seek to create a kind of “interaction and evaluation” (Hyland 2005) that is indispensable to writing in academic disciplines.

Academic writing involves more than facts; it involves ‘positions’, taking sides in relation to both the propositions discussed in the text, to existing research, and researchers who have published on those issues and propositions. So, academic writing is not only about ideas but also about connecting people and connecting people and ideas. Moreover, as Hyland (2005) argues, the rationale for writer-reader interaction arises out of the fact that “readers can always refute claims” unless they are persuaded by a valid and compelling argument. Accordingly, readers have “an active and constitutive role in how writers construct their arguments” (p. 176). So, writers need to predict, accommodate, and/or respond to possible concerns and reactions from the potential audience.

Interaction in Academic Texts

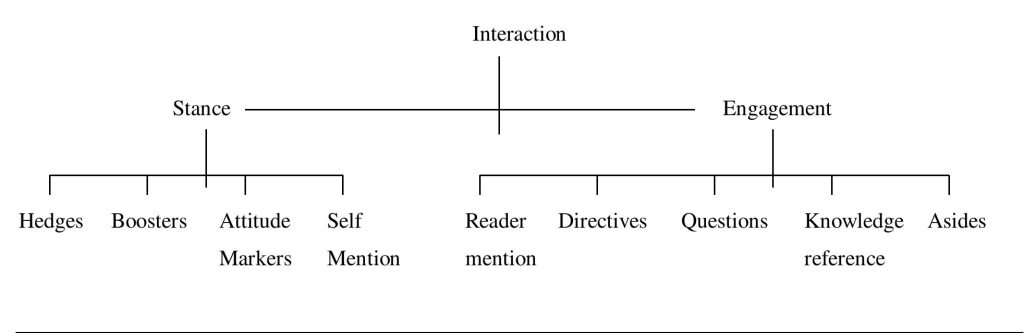

The model in Figure 1 proposes that writers interact with their audience in two main ways, or in Hyland’s (2005) terms, using the two sides of the same coin (p. 176). These are stance and engagement. Briefly defined, stance refers to how writers express themselves and their voice and communicate their opinions, evaluations, and commitments regarding the topic under research and the people who have already published on it. In taking a stance, writers may choose to expose their personal authority in intrusive ways or rather mask their involvement.

As the other side of the academic interaction coin, engagement denotes the ways writers acknowledge the active participation of their readers, seek their attention, respond to their concerns, and lead them throughout the text to their intended interpretations and conclusions.

The following paragraphs elaborate on the key resources and linguistic markers by which stance and engagement functions are realized in academic texts.

Note. From Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse” by K. Hyland, 2005.

Strategies to identify your stance

Hedges

These present information as an opinion. By hedging, a writer withholds absolute commitment to a proposition or claim, thus avoiding the risk of being refuted by the reader. Instances of hedges are: “may,” “might,” “at least,” “perhaps,” “seem,” “suggest,” and “appear.”

Boosters

These are certainty markers. Writers use boosters to express their assurance over the knowledge claim or evaluation. Some linguistic boosters are: “clearly,” “obviously,” “surely,” “highly,” “it is clear that.”

Attitude markers

These convey writers’ affective attitudes to propositions. They may be realized as verbs (“prefer,” “agree,” “propose”); adverbs (“unfortunately,” “interestingly,” “hopefully”); adjectives (“logical,” “remarkable,” “appropriate,” “sufficient”).

Self-mentions

These concern the use of first-person pronouns and possessive adjectives (I, we, my, our).

It is a common convention for academic writing to use the third-person voice and, in turn, avoid I pronouns, because it is generally the case that the third-person voice is seen as more formal. It is definitely the case that third-person voice can create an impression of objectivity, that the implied speaker (the author) of the text is unbiased. And since the readers of academic writing are usually most interested in the information and ideas being presented, they might not find a first-person speaker’s personal experiences directly relevant to the purpose and context of the text. For example, if your readers mostly want to hear your ideas about campus security, you don’t need to write “I conducted a lot of research to determine what I think about possible campus security reforms”—you can simply tell your readers what you think about campus security reforms. This is why some teachers advise against using I (first-person pronouns) in academic writing.

But note that first-person voice isn’t necessarily informal any more than third-person voice is necessarily formal. You can be flashy, formal, or ornate while writing about your personal experience, or really casual and colloquial while describing something from a distance. More importantly, sometimes personal experience is directly relevant to a subject being discussed. If you are writing an academic essay about attempts by scientists to eradicate the facial tumour disease affecting Tasmanian devils, it probably doesn’t make sense for you to share your personal experiences and thus use the first-person voice. But if, for instance, you have been skiing competitively since you were a child and have seen friends and competitors struggling to recover from concussions caused by skiing accidents, it could be very effective for you to share your personal experiences (and use the pronoun I) in an academic essay arguing for a public health campaign to get skiers to wear helmets. A rule that tells you to always or never use “I” in your essays isn’t necessary – instead, you should think about what will be appropriate given the larger rhetorical situation.

It is also important to note here that even disciplines like biological sciences, which have traditionally relied on the third-person voice in writing, are now more accepting of the first-person pronouns “I” and “we,” as they add important clarity to the writing.

Strategies to engage your reader

Reader pronouns

Using pronouns such as “you,” “your,” and the inclusive “we” helps to acknowledge the readers’ presence and get them onside.

Directives

These require the reader to perform an action. Example: note, let, assume; necessity modals: should, need to, ought; It is …: It is critical to do;

Questions

Questions engage the readers’ interest and curiosity, encouraging them to follow the argument the writer has structured in the text. Example: “Is it, in fact, necessary to choose between nurture and nature? My contention is that it is not.” Hyland (2005, p. 186)

Appeals to shared knowledge

These are explicit markers where readers are asked to recognize something as familiar or accepted, as in the following example: “Of course, we know that the indigenous communities of today have been reorganized by the catholic church in colonial times and after,…” (Hyland, 2015, p. 183)

Personal asides

These devices allow writers to briefly interrupt the argument to offer a comment on what has been said, as in the following example from Hyland (2015, p. 183): “And – as I believe many TESOL professionals will readily acknowledge – critical thinking has now begun to make its mark…”

Remember: Disciplines use different strategies

It is important to note that the use of strategies to identify your stance and to engage your reader varies across disciplines. Analyze texts in your discipline to uncover which strategies are best suited to your field. When in doubt, you should always ask your instructor.

References

Bakhtin, M. (1986). The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (ed. M. Holquist, trans. C. Emerson and M. Holquist). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Studies, 2(7), 173 – 192.

Attributions

“Mastering Stance and Engagement” by Shahin Moghaddasi Sarabi, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and includes material from:

- “Framing Your Research for Readers: Interaction, Engagement, and Stance” by Shahin Moghaddasi Sarabi, Writing Across the Curriculum, Centre for Teaching and Learning, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- “5.8 Voice” by Erin Kelly; Sara Humphreys; Natalie Boldt; and Nancy Ami, Why Write? A Guide for Students in Canada 2nd Edition is licensed under CC BY 4.0