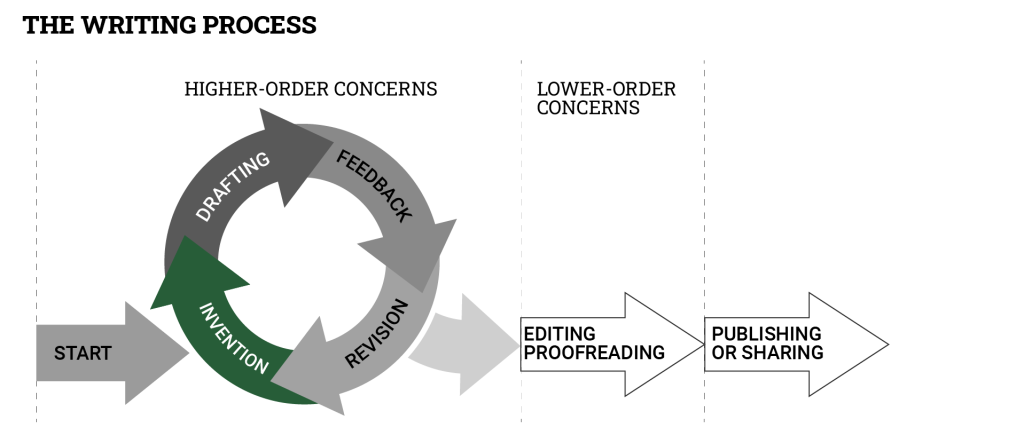

Section 2: The Writing Process

Invention

Invention is the first stage of the writing process (see Figure 1). You are probably familiar with this stage, although you may have called it brainstorming, pre-writing or planning. The invention process aims to develop ideas that lay the foundation for your draft. In this stage, you may research your topic, write notes to generate ideas, doodle a mindmap, or absent-mindedly think about the project while doing other things. The invention stage is important because starting to draft before you are ready can lead to a miserable experience. You might get stuck and end up staring at a blank screen or page because you don’t have enough ideas or your ideas aren’t sorted out sufficiently yet. You may find yourself returning to the invention stage as you work to improve your drafts.

You can use several different invention techniques to help build material for a draft. Think of the list of invention activities below as a list of recipes: Some recipes will be exactly to your taste, and you will use them repeatedly. Others won’t be tasty or won’t work for your cooking style. However, you should try as many techniques as possible to find something that works for you. A good invention process will lead to a smoother drafting process.

Freewriting

Freewriting is writing without considering grammar, punctuation, spelling or organization. Freewriting is fast writing done in short sessions of five to twenty-five minutes. It is usually private writing that doesn’t get shared with others – this privacy means you are free to make a mess without fearing judgment.

Why freewriting?

Freewriting helps you to use writing to develop ideas. When we write, we often focus on editing our words and sentences. We might write a sentence, change a few words, and then delete the sentence. While doing this, we juggle all the writing advice and rules we have learned. Consider these editorial voices in your head as your “editor muscle.” The problem with the editor muscle is that it doesn’t help us when we need to generate ideas and develop our early drafts. It can often get in the way of writing by forcing us to focus on surface-level issues rather than digging deeper to find interesting and creative ideas.

When we learn to write, we often develop very strong editor muscles–our schooling emphasizes this aspect of writing. Imagine yourself as the fiddler crab in Figure X; one side of your body is oversized and powerful, while the other is small and weak. Now, imagine how difficult it would be to walk easily if you only worked out on one side of your body. This analogy also applies to writing: if your editor muscle is strong and your creative muscle is weak, you will likely run into balance issues as you write.

Note. From “Fiddler Crab” by Wilfredor, 2013, CC0 1.0.

Freewriting helps us balance the editor muscle by developing an equally strong creative muscle. A well-developed creative muscle can turn off the editorial voices in your head and use writing to make connections and develop your ideas more efficiently. Building up a strong creative muscle makes the writing process more balanced: You are less likely to get stuck, and you may find joy in developing ideas with words.

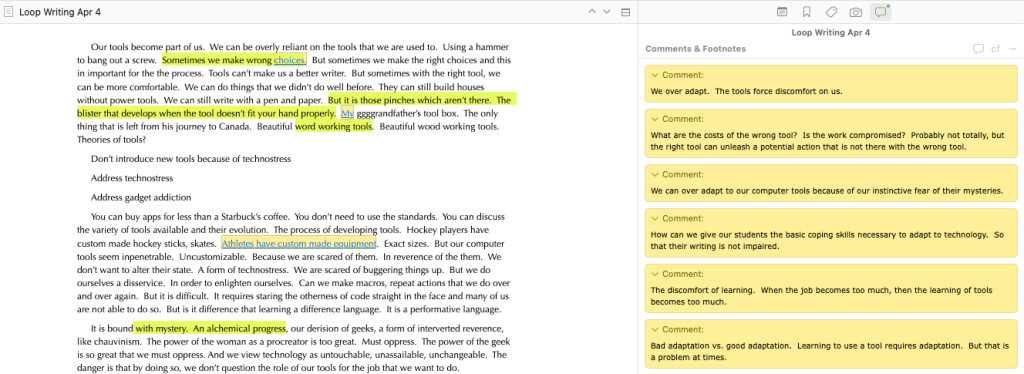

After a session of freewriting, put your work aside. Return to it in a day or two, and read it carefully. Highlight interesting ideas and ask yourself questions and comments about your ideas. Figure X shows an example of my freewriting with highlighted passages, questions, and comments I asked myself as I read.

Freewriting produces raw writing, which may not become part of your final draft. For some people, this feels too indirect; for others, freewriting helps them to develop more complex ideas and organize their thoughts.

Types of freewriting

Unprompted freewriting

You can freewrite without a focused prompt or guiding question in mind. This approach could help clear your mind or help you to sort out broad ideas about a topic. To freewrite using this method, you simply have to sit down, set a timer, and write freely. Write as quickly as possible without paying attention to organization, grammar, punctuation, or spelling.

Unprompted loop writing

Peter Elbow, a prominent writing studies scholar, developed a form of unprompted freewriting called loop writing. To loop write, write freely about a topic for a short time. Read your writing and identify the “centre of gravity” or most compelling idea in your freewriting. Then, write freely again, focusing on the centre of gravity from your first freewriting session. You can continue looping like this to add depth to your ideas on a topic.

Prompted freewriting

Prompted freewriting is when you are given a particular question or phrase–a prompt–to focus on. Sometimes, you can develop your own prompts. For instance, if you have two ideas for a piece of writing but are unsure how to connect them, you could freewrite, focusing on the potential connections between the ideas. Other times, you may be given a particular prompt by your instructor, or you could use a set of pre-existing prompts. For example, you could try one of the following prompted freewriting activities.

Perl’s Composing Guidelines

Perl’s Composing Guidelines is a set of freewriting prompts that help you develop ideas for a new writing project (Elbow & Belanoff, 2000). These guidelines were developed by writing studies scholar Sondra Perl based on the ideas of the philosopher Eugene Gendlin. Gendlin coined the term “felt sense” to describe a physical sense of knowing something that we haven’t yet been able to put into words. In Perl’s Composing Guidelines, the prompts ask you to pay attention to your felt sense to discover possible topics and approaches for a writing project.

The “Additional Resources” [hyperlink] section at the bottom of this page provides information on how to learn more about Perl’s Composing Guidelines.

Cubing

Cubing is a short freewriting activity that helps you to examine your topic from different angles. There are six prompts in the cubing activity: one for each side of a cube. Don’t spend more than three or four minutes on each of the following prompts.

- Describe your topic. What do you see? Describe colours, shapes, sizes, and anything else that comes to mind.

- Compare it. What is your topic similar to? What is it different from?

- Associate it. What does your topic make you think of? Let your mind wander, and write down any associations you can make to your topic.

- Analyze it. Do your best to write down how your topic is made. That is, separate it into different parts and write down these parts. Write down how you think these parts are connected.

- Apply it. How can your topic be useful? What can you do with it?

- Argue for or against your topic. Take a stand about your topic. Use any type of evidence that comes to your mind.

Cubing was first described by Greg and Elizabeth Cowan in Writing (1980).

Prompted loop writing

In addition to his unprompted loop writing exercise, Peter Elbow (1981) developed a series of prompts to guide writers through a freewriting activity. These prompts are particularly useful after you have done some invention work and have some ideas about your topic. They force you to consider an issue from many perspectives, helping enrich your ideas. The prompts for this activity are as follows:

- What you know. Write down what you already know about the topic.

- Prejudices. Write about your topic from a biased perspective. Don’t censor yourself.

- Instant Version. Pretend that you know everything you need to know about the topic. Start writing your final version.

- Dialogues. Write a dialogue between the conflicting voices or perspectives on your topic.

- Narrative. Write the story of how your thinking on this topic has developed.

- Stories. Write down stories or events surrounding the topic.

- Scenes. Take still photographs in your mind of moments related to your topic. Describe these imaginary scenes.

- Portrait. Write short vignettes of the people related to your topic.

- Vary the audience. Write to an audience other than the intended audience for your writing.

- Vary the writer. Write as though you are someone with a different perspective on your topic.

- Vary the time. Write about your topic as though you are living in the past or the future.

- Errors. Write down ideas that are almost true about your topic.

- Lies. Write down strange or crazy ideas about your topic.

Inkshedding

Inkshedding is a form of shared freewriting developed by Canadian writing studies scholar Russell Hunt (2005). The main difference between inkshedding and freewriting is that writers know this writing will be shared before they sit down to write. Typically, writers are asked to inkshed after a shared experience, like listening to a conference presentation or reading something. Writers write freely on their ideas about the shared experience in their inksheds. The inksheds are then exchanged with other writers who highlight interesting passages.

Inkshedding helps to draw out the social nature of writing; it makes the communication between the writer and the reader visible. This activity also ensures that every participant has their voice heard–something impossible in a group discussion.

Inkshedding can be scary initially because it requires sharing your raw writing and “top of the mind” responses with others. However, once you overcome your initial fears, inkshedding is a powerful activity that helps us understand how writing builds community.

Visual Invention Techniques

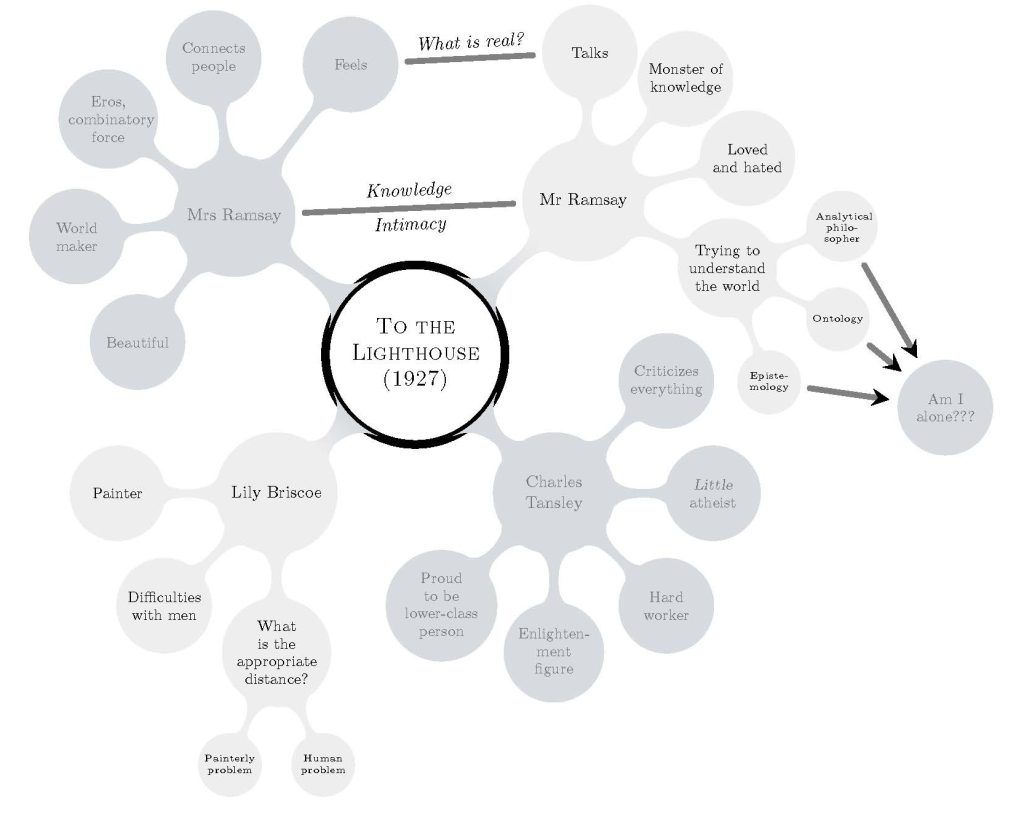

Mindmaps

A mindmap is a visual invention technique. At the centre of your document, you write down your topic. You add ideas which relate to the topic around the centre, attaching them to the central idea with a line. Repeat this process with your sub-topics, adding more relationships and details as you move out of the central topic. Figure X shows a mindmap developed for an essay about the novel To the Lighthouse by Virginia Wolff.

Note. From Wikimedia Commons by V. Repin, 2013, CC BY-SA 3.0.

For mind mapping to be effective, you should build your map to at least the third or fourth level. Otherwise, your thinking about your topic remains too superficial, and you may not find connections that enrich your writing.

Visual scrapbook or collage

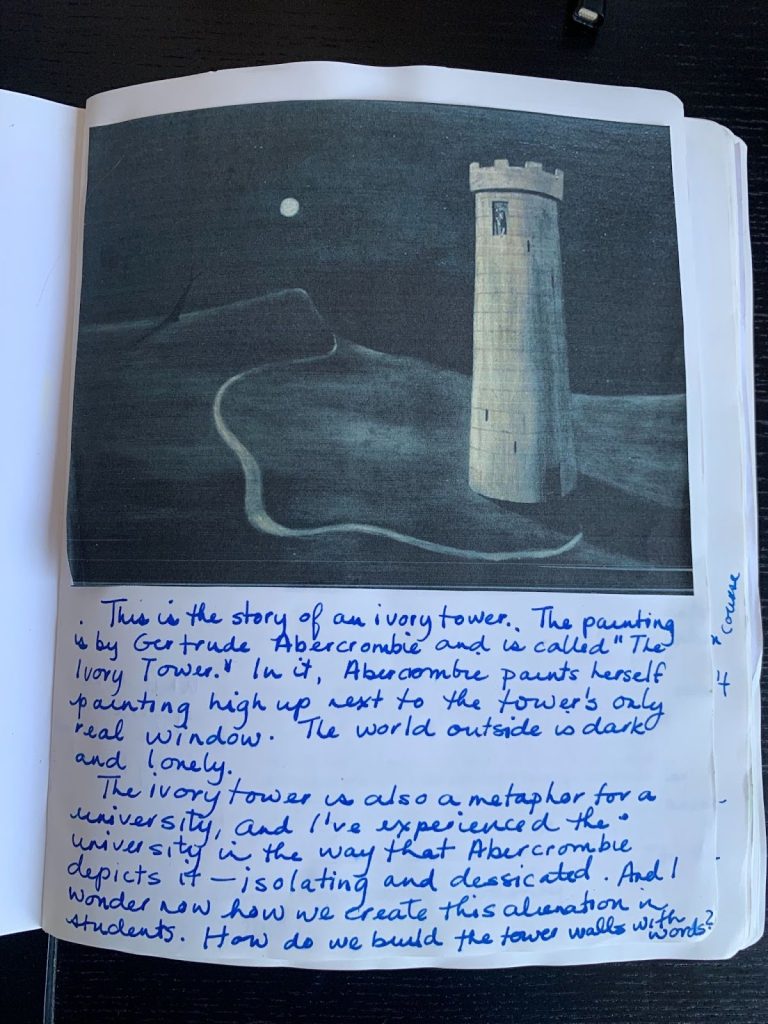

Writers sometimes make visual scrapbooks or collages to help them develop project ideas. For instance, you can browse the Internet for images related to your topic. Copy them into a document and comment on the relationship between your topic and the image. You can also print out the image and create a physical scrapbook. This technique is especially useful for a complex project. Figure X shows a page in a scrapbook that I kept as I worked on a writing project about academic writing.

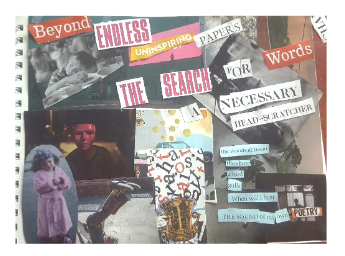

You could also create a collage that gathers images relating to your topic. A collage asks you to combine images into one large image, forcing you to juxtapose ideas and consider their relationship. Figure 6 shows an example of a collage produced by Brittany Amell as she generated ideas for her co-written paper “Engaging with Play and Graduate Writing Development” (p. 38).

Note. From “Engaging with play and graduate writing development” by B. Amell and E.M. Blouin-Hudon, 2018.

Spoken Invention Techniques

Speech-to-text

If you prefer oral communication to writing, you may find speech-to-text software helpful in the invention phase. You can use the freewriting approach when you use this software. For instance, you can speak freely for a few minutes about your topic while the software records your words. You can also use the freewriting prompts or activities listed above to guide your speech about your topic. Because this software sometimes makes mistakes as you speak, the output looks like freewriting’s messy, raw writing.

Discuss your topic

Here’s a tried and true method to develop ideas for a paper. Talk about your topic with a loved one, friend, classmate, instructor, or writing centre tutor. Sometimes, this is a surprisingly easy and effective method to gather ideas and work out areas of confusion.

Using Generative AI for Invention

Consider academic integrity

- Please confirm with your instructor, course syllabus and your institution’s policies if you can use Generative AI to help you develop ideas for a project.

Use it effectively

- Generative AI can be helpful as a conversational assistant when you are in the invention stage of a project.

- Be sure to use effective prompts that provide important context. For instance, tell the Generative AI tool that you are an undergraduate student writing a research paper for a particular course. Provide the name of the course. Be clear about what types of suggestions you want and what kinds of suggestions you don’t want. After the initial prompt, be sure to follow up with questions that help to refine the ideas.

Beware of the limitations

- Generative AI may provide you with biased and inaccurate information. The training data provided to Generative AI may include biases that will be reflected in the responses that you receive.

- Generative AI may plagiarize the sources used in its training database.

Consider your learning journey

- If you rely on Generative AI in the invention stage, you may not have the chance to consider original and creative ideas. Missing out on exploring these ideas may lead to less interesting writing and academic work.

Consider ethics

- Consider the ethical implications of using these tools. Ensure that the ideas generated with Generative AI do not infringe on others’ copyright. Make sure you acknowledge your use of Generative AI in the acknowledgements section of your work.

Additional Resources

If you want to try Perl’s Composing Guidelines, watch this series of videos that guide you through the prompts or read the text prompts at “Sondra Perl’s Composing Guidelines.”

References

Amell, B., & Blouin-Hudon, E.-M. C. (2018). Engaging with play and graduate writing development. Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie, 28, 33–56. https://doi.org/10.31468/cjsdwr.606

Cowan, G., & Neeld, E. C. (1980). Writing. John Wiley & Sons.

Comp Comm. (2015). Guidelines for composing [Video Playlist]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL978ckNHtV5sQ47tfFqOFXXy9Kv6QCG_H

Elbow, P. (1981). The loop writing process. In Writing with power: Techniques for mastering the writing process (pp. 59-77). Oxford University Press.

Elbow, P., & Belanoff, P. (2000). A community of writers : a workshop course in writing (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Hunt, R. (2005). What is inkshedding. http://people.stu.ca/~hunt/www/whatshed.htm

The International Focusing Institute. (2025). Sondra Perl’s composing guidelines. The International Focusing Institute. https://focusing.org/articles/sondra-perls-composing-guidelines-0

Attributions

“Invention” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Fiddler Crab” by Wilfredor, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0

“Freewriting with Highlighted Passages, Questions, and Comments” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Mindmap Exploring Themes and Characters in the Novel To the Lighthouse” by Vitaly Repin, Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“A Scrapbook Page Developed for a Project on Academic Writing” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“A Collage as Invention Activity” by Brittany Amell, Engaging with play and graduate writing development, Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0