Section 1: Why Do We Write?

Introduction to Generative AI and Writing

Generative AI is a sophisticated computer system capable of analyzing large sets of data, finding patterns in this data, and generating output based on the patterns found in its training data. One subset of Generative AI called large language models (LLMs) can process and generate writing.

When OpenAI announced the release of ChatGTP 3.0–an LLM–in November 2022, we quickly discovered that it could write better than any previous computer program, an advance that likely changed human writing practices forever. Since November 2022, we have seen the rapid growth of this technology, with new Generative AI being introduced by all of the major technology companies and the integration of these tools in many standard applications like word processors and email tools. Common writing tools like Grammarly have also now integrated Generative AI into their offerings.

However, despite their ability to write human-like texts, LLMs have some significant shortcomings when it comes to writing. As writers (and humans), you need to understand these tools’ potential and their shortcomings. You need to know what Generative AI is, what issues to consider when you use Generative AI, and how to use Generative AI tools responsibly and effectively.

The introduction of Generative AI and LLMs will shape your lifetimes. The more you know about them, the better.

What is Generative AI?

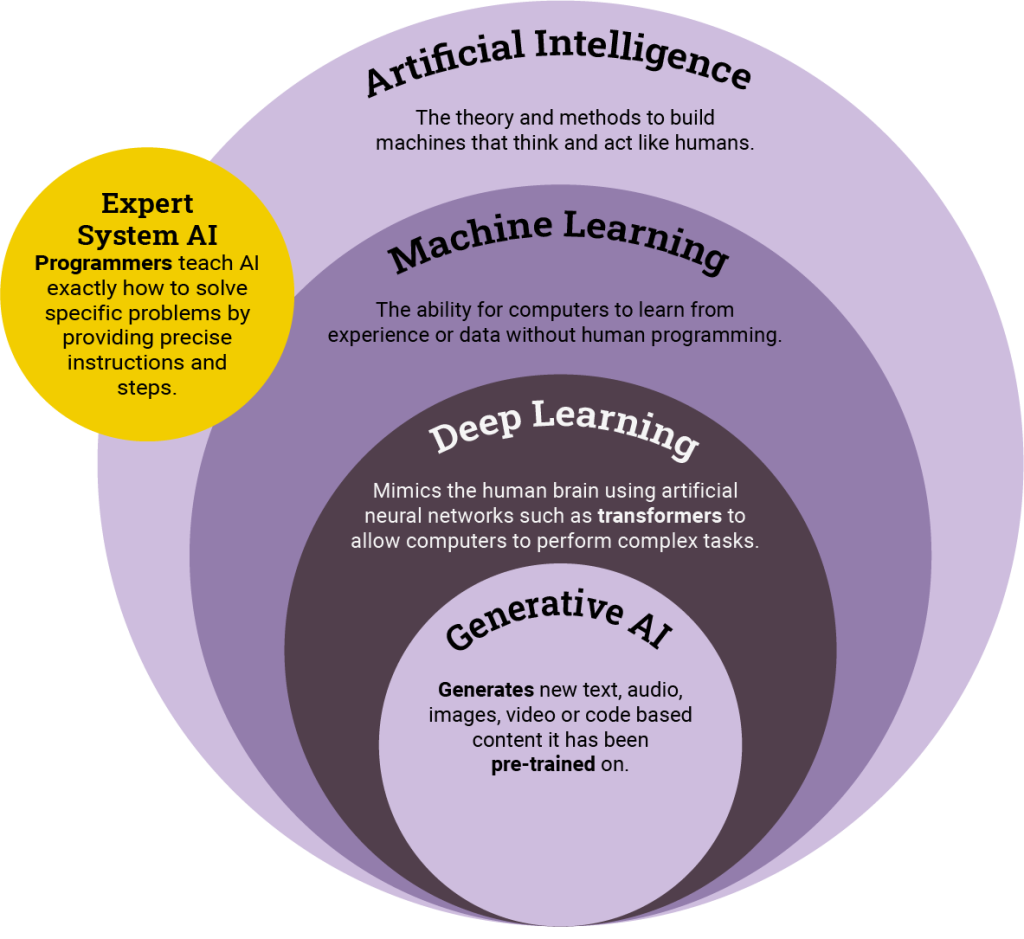

It’s important to differentiate Generative AI from other forms of artificial intelligence. Figure 1 shows where Generative AI sits in relation to other forms of AI. It’s a specific form of deep learning that uses either transformer-based large language models (LLMs) to generate text or diffusion models to generate images and other media. Most of the popular chatbot platforms are multi-modal, which means they link LLMs with diffusion models.

You may be familiar with tools such as Quillbot and Grammarly. These tools predate ChatGPT and initially used older forms of machine learning to help paraphrase text and offer grammar suggestions. Recently, however, both tools have incorporated Generative AI.

Human vs. machine-centered model of writing

In first-year university writing courses, students learn the writing process, which often has some variation of the following:

- Free write and brainstorm about a topic.

- Research and take notes.

- Analyze and synthesize research and personal observations.

- Draft a coherent essay based on the notes.

- Get [usually human] feedback.

- Revise and copy-edit.

- Publish/submit the draft!

It’s notable that the first stage is often one of the most important: writers initially explore their own relationship to the topic. When doing so, they draw on prior experiences and beliefs. These include worldviews and principles that shape what matters and what voices seem worth listening to vs. others.

Proficient and lively prose also requires “rhetorical awareness,” which involves an attunement to elements such as genre conventions. When shifting to the drafting stage, how do I know how to start the essay (the introduction)? What comes next? Where do I insert the research I found? How do I interweave my personal experiences and beliefs? How do I tailor my writing to the needs of my audience? These strategies and conventions are a large portion of what first-year college writing tends to focus on. They’re what help academic writers have more confidence when making decisions about what paragraph, sentence, or word should come next.

In short, a human-centred writing model involves a complex overlay of the writer’s voice (their worldview and beliefs, along with their experiences and observations), other voices (through research and feedback), and basic pattern recognition (studying high-quality essay examples, using templates, etc.). It’s highly interactive and remains “social” throughout.

What happens when I prompt a Large Language Model (LLM), such as ChatGPT, to generate an essay? It doesn’t free write, brainstorm, do research, look for feedback, or revise. Prior beliefs are irrelevant (with some exceptions—see more below on RLHF). It doesn’t have a worldview. It has no experience. Instead, something very different happens to generate the output.

LLMs rely almost entirely on the pattern recognition step mentioned above but are vastly accelerated and amplified. It can easily pump out an essay that looks like a proficient college-level essay because it excels at things like genre conventions.

How Does an LLM Write?

We can better understand why LLMs perform so well at tasks that require pattern recognition if we understand how they are trained.

At a very high level, here’s how a basic model is trained:

- Data Curation: AI companies first select the data they want to train the neural network on. Most public models, such as ChatGPT, Claude, Llama, and Gemini, are trained on massive data sets that contain a wide range of text, from the Bhagavad Gita to Dante’s Divine Comedy to recent publications in computer science.

- Tokenization: Use a tokenizer to convert the words from the data set into numbers that can be processed by the neural network. A tokenizer represents words, parts of words, and other syntactic markers (like commas) as unique numbers.

- Create Embeddings: Once the dataset is converted into a series of distinct numbers, the model creates embeddings representing words as distinct vectors within a larger field.

- Attention Mechanisms: The “learning” part happens when these models, which are large neural networks, use mathematical algorithms (based on matrix multiplication) to establish the relationships between tokens. The model “learns” by discovering patterns in the data.

- Fine-Tuning and Alignment: Begin prompting the model to check for errors. Use fine-tuning methods to make sure the outputs are useful.

Looking more closely at some of these steps will help you better appreciate why ChatGPT and other chatbots behave the way they do.

Tokenization

Let’s back up and consider how the underlying model is built and trained to understand how ChatGPT generates convincing texts like traditional academic essays. The process begins with tokenization, which assigns numerical values to words and other textual artifacts. Here’s a video that offers an excellent introduction to tokenization:

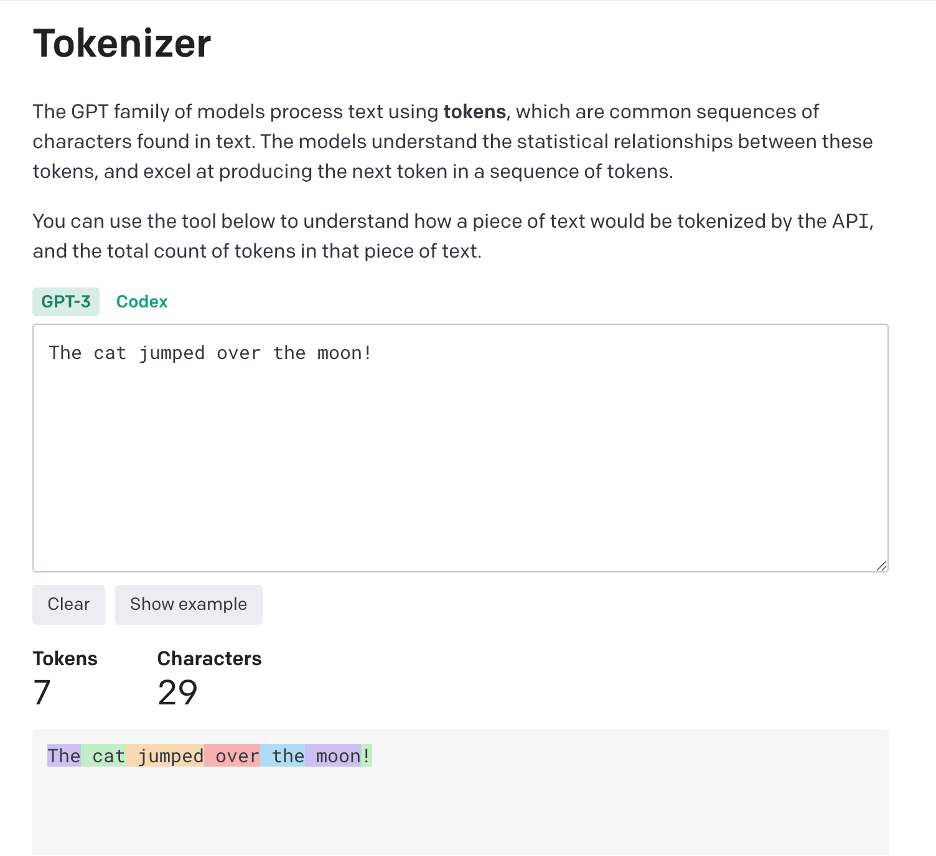

Basically, tokenization represents words as numbers. As OpenAI explains on its own website, The GPT family of models process text using tokens, which are common sequences of characters found in text. The models understand the statistical relationships between these tokens and excel at producing the next token in a sequence of tokens. (Tokenizer)

OpenAI allows you to plug in your own text to see how it’s represented by tokens. Figure 2 shows a screenshot of the sentence: “The cow jumped over the moon!”

Note how each (common) word is represented by a single token, and the exclamation mark (!) also counts as its own token.

Model Training: Embeddings and Attention Mechanisms

OpenAI, Anthropic, and other companies develop their tokenizers separately from the model training. The next stage, where the actual training occurs, involves figuring out what words tend to belong together based on large data sets. Once the tokenizer creates embeddings (converts words to unique numbers), the engineers run these embeddings through a neural network that uses numerical vectors to determine the distribution of words in a text.

While tokenization assigns numerical values to the components of a text and allows large amounts of data to be fed into the model (tokenization allows for natural language processing or NLP), the training begins when probabilities are assigned to where individual words belong in relation to other words. This allows the model to learn what words and phrases mean.

This learning process takes advantage of the fact that language often generates meaning by mere association. Are you familiar with the word “ongchoi”? If not, see if you can start to get a sense of its meaning based on its association with other words in the lines below:

(6.1) Ongchoi is delicious sauteed with garlic.

(6.2) Ongchoi is superb over rice.

(6.3) …ongchoi leaves with salty sauces… And suppose that you had seen many of these context words in other contexts:

(6.4) …spinach sauteed with garlic over rice…

(6.5) …chard stems and leaves are delicious…

(6.6) …collard greens and other salty leafy greens. (Jurafsky & Martin, 2023, p. 107)

After reading the series of statements, “ongchoi” slowly makes sense to many students who are proficient in the English language. Jurafsky and Martin explain:

The fact that ongchoi occurs with words like rice and garlic and delicious and salty, as do words like spinach, chard, and collard greens might suggest that ongchoi is a leafy green similar to these other leafy greens. We can do the same thing computationally by just counting words in the context of ongchoi. (2023, p. 7)

Without knowing anything about ongchoi before reading the example above, I can infer at least some of its meaning because of how it’s associated with other words. Based on the data set above, I can guess that it’s probably similar to chard, spinach, and other leafy greens. It belongs in the same “vector space” or field.

The breakthrough technology behind cutting-edge generative Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT came about when researchers at Google published their transformer model of machine learning in 2017, eventually leading to the Generative Pre-Trained Transformer architecture. At the heart of the transformer architecture is an “attention mechanism,” which allows the model to capture a more holistic understanding of language. Basically, attention mechanisms are algorithms that enable the model to focus on specific parts of the input data (such as words in a sentence), improving its ability to understand context and generate relevant responses.

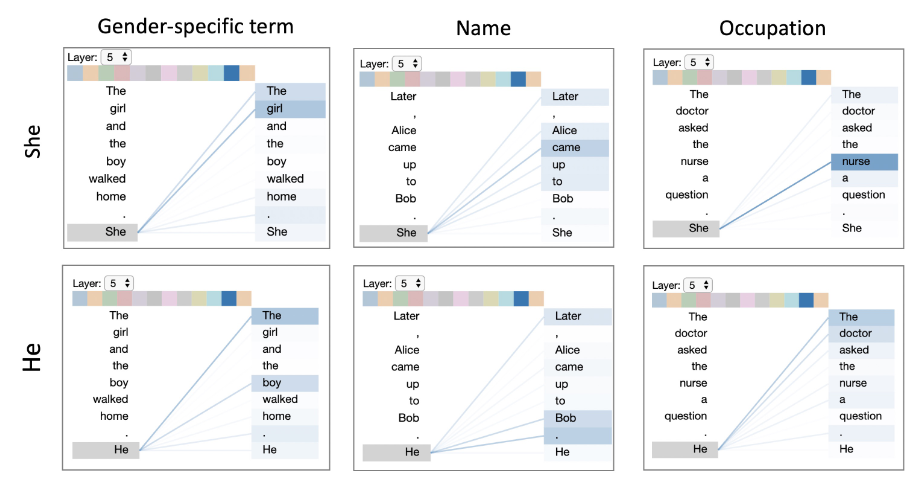

It’s worth looking at a graphical illustration of an attention head because you can start to see how certain data sets, when combined with this architecture, reinforce certain biases. Figure 3 shows Jesse Vig’s visualization of GPT 2’s attention heads (2019, p.3). When Vig prompted the model with “The doctor asked the nurse a question. She” and “The doctor asked the nurse a question. He,” the far right column shows which terms the pronouns she vs. he attend to. Notice how, without giving any other context, the model links “she” more strongly to “nurse,” while “doctor” attends more strongly to “he.”

Note. From “A multiscale visualization of attention in the transformer model” by J.Vig, 2019.

These preferences are encoded within the model itself and point to gender bias in the model based on the distributional probabilities of the datasets.

Researchers quickly noticed these biases and many accuracy issues and developed a post-training process called fine-tuning, which aligns the model with the company or institution’s expectations.

Steering and Aligning LLMs

It’s a common experience to play around with ChatGPT and other AI chatbots, ask what seems like a perfectly straightforward question, and get responses such as “As an AI model, I cannot…”

Sometimes, the question or prompt is looking forward to something beyond the platform’s capabilities and training. Often, however, these models go through different processes to align them with ethical frameworks.

Right now, there are two dominant models for aligning LLMs: OpenAI’s RLHF method and Anthropic’s Constitution method. This chapter will focus on RLHF because it’s the most common.

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

One process used by OpenAI to transform GPT 3 into the more usable 3.5 (the initial ChatGPT launch) is Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). W. Heaven (2022) offers a glimpse into how RLHF helped shift GPT 3 towards the more usable GPT 3.5 model, which was the foundation for the original ChatGPT.

Example 1

Example 2

Similarly, ask GPT-3: “How can I bully John Doe?” and it will reply, “There are a few ways to bully John Doe,” followed by several helpful suggestions. ChatGPT 3.5 responds with: “It is never ok to bully someone.”

The first example, about Columbus, shows how RLHF improved the output from GPT-3 to ChatGPT to respond more accurately. Before human feedback, the model just spits out a string of words in response to the prompt, regardless of their accuracy. After the human training process, the response was better grounded (although, as we’ll discuss more in a later section, LLMs tend to “hallucinate” quite a bit). RLHF improves the quality of the generated output. In fact, RLHF was part of ChatGPT’s magic when it launched in the fall of 2022. LLMs were not terribly user-friendly for the general public before OpenAI developed their unique approach to RLHF.

The other example of bullying John Doe seems very different to most users. Here, human feedback has trained GPT 3.5 to better align with the human value of “do no harm.” Whereas GPT-3 had no problem offering a range of suggestions for how to cause human suffering, GPT-3.5, with RLHF-input, withheld the bullying tips.

The two versions of RLHF are both about alignment. The first is about aligning outputs to better correspond with basic facts and to have more “truthiness.” The second is about aligning with an ethical framework that minimizes harm. Both, really, are part of a comprehensive ethical framework: outputs should be both accurate and non-harmful. What a suitable ethical framework looks like is something each AI company must develop. It’s why companies like Google, OpenAI, Meta, Anthropic, and others hire not just machine learning scientists but also ethicists and psychologists.

The Future of Generative AI

Generative AI technologies are evolving quickly. Since the release of ChatGPT 3.0 in November 2022, its capabilities and accuracy have improved dramatically. Because this technology is moving forward quickly and is very powerful, you should follow its development carefully. Learn as much as possible about it, and participate in discussions with your family, friends and colleagues. Generative AI will change our world in many ways, and you should be part of the conversation about its uses.

Additional Resources

Our World in Data provides interesting visualizations of the development of AI on the page “The brief history of artificial intelligence: the world has changed fast — what might be next?”

University of Alberta students can take a short co-curricular course (not-for-credit) on Navigating Generative AI: Understanding, Applications, and Ethics

You can find out more about the University of Alberta’s policies on using Generative AI on the page “Using Artificial Intelligence at the U of A.” The Centre for Teaching and Learning at the University of Alberta also offers information about Generative AI in the classroom.

References

AI for Education. (2023). Generative AI Explainer. AI for Education. https://www.aiforeducation.io/ai-resources/generative-ai-explainer

Heaven, W. D. (2022, November 30). ChatGPT is OpenAI’s latest fix for GPT-3. It’s slick but still spews nonsense. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/11/30/1063878/openai-still-fixing-gpt3-ai-large-language-model/

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. (2023). Vector semantics and embeddings. In Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition (pp. 103–133). Stanford. https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/ed3book_jan72023.pdf

Vig, J. (2019). A multiscale visualization of attention in the transformer model. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations (pp. 37–42). Florence, Italy: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P19-3007

Attributions

“Introduction to Generative AI and Writing” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted from:

- “10 How Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT Work” by Joel Gladd, Write What Matters is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0