Section 3: What is Academic Writing?

Academic Writing as Persuasion

When it comes to academic writing, the purpose of every piece of writing is to make an argument, although the term “argument” in this context might need some definition. You may be tempted to think of an argument as a tense emotional conflict; however, an argument doesn’t only mean getting into a fight with someone. An argument is an attempt to persuade an audience by making a claim and supporting it with evidence. Arguments over ideas are common in academic writing, as we want to persuade our readers that our knowledge and ideas have value and should be adopted.

Before we explore the components of an argument, let’s consider persuasion and think about the persuader and those whom the persuader wants to persuade (otherwise known as the rhetor and the audience). Rhetorician Kenneth Burke redefined the concepts of argument and persuasion to better suit Western culture. In Western cultures, relationships are often unequal, and so Burke argued that persuasion is more akin to a historical idea of courtship (the word “courtship” is a rather outmoded way to define dating) rather than an argument between equal parties:

An audience’s degree of adherence to the rhetor’s argument can vary greatly. By contrast, courtship focuses primarily on the unequal relationship between the persuader and those being persuaded, rather than employing means generally considered “persuasive.” Through courtship, the “courtier” already commands a certain “captivation” of the audience. This “courted” audience thus yearns to transcend the gap of social estrangement to unite with the persuader. (Ramage, Callaway, Clary-Lemon, & Waggoner, 2009)

Now, the idea here isn’t to literally court someone. By “courtship,” Burke refers specifically to courtiers, who had permission to enter the court where they might receive audience with a monarch and other noblemen. Courtiers (like lobbyists, in a way) “court” those in power for various benefits for themselves, their communities, families and so on. This relationship, in some ways, is not unlike when a professor submits a paper for publication and must write a letter (or email of introduction) courting the press with persuasive language (and a certain amount of deference) so that they consider the paper for publication.

Extending Burke’s analogy a little more, when you are writing an assignment, you might feel anxious. This anxiety occurs, in part, because you are working to show a person in authority (your instructor) that you possess certain knowledge. You are “courting” a person who has some authority in order to gain something. In this case, a grade. Luckily, you are not a courtier, and your instructor is certainly there to support you. This analogy, however, serves as a means to consider the relationship between the rhetor and the audience (who are often, but not always, unequal).

When you engage in acts of persuasion, you are hoping to induce action in others. To show you just how common persuasion is in communication, here are a few common examples you might recognize where students want to persuade or induce action:

- You write an email to one of your instructors asking them to grant you an extended deadline for your next essay assignment. In doing so, you are persuading your instructor to give you something.

- One of your friends says that your favourite movie is boring, so you present all the reasons you can think of why this film is interesting. In this case, you are trying to change someone’s mind.

- Your brother is sure that vaping is much safer than smoking cigarettes. You are increasingly convinced that vaping can cause serious health problems. When you show your brother pamphlets and news articles that discuss the dangers of vaping, you are working to change someone’s perspective.

- You and your group members need to pick a topic for your class presentation. Some of you want to create a presentation about the need for better mass transit in your community. Others want to learn and talk about how to design more fuel-efficient cars. Others want to focus on the effects of dedicated bike lanes. As you help everyone decide on and agree to focus on a single topic, you are getting those in disagreement to come to a consensus.

- You are asked to give a speech at your friend’s surprise birthday party. Everyone at the party – other friends and family members – thinks your friend is a terrific person. You try to craft a speech that gets everyone to remember and reflect on how much they like your friend. With this speech, you are trying to reinforce ideas that people already have.

- You know a lot about local birds and find them fascinating. You write a post that will be posted on a community blog. Those who read it haven’t given much thought to birds. As you share your knowledge, you are trying to get people to think that what you are saying is correct.

Aristotle’s Three Rhetorical Appeals

Even if you are trying to achieve the same end-goal with an argument, you likely know from experience that you wouldn’t make an argument in the same way to every person you encounter. For example, let’s say you are a cinephile (someone who LOVES movies). You want to get the friends and family members who have gathered together for a holiday meal to end the day by going out to see a particular classic movie that is showing at your local independent cinema.

For your mom, who thinks movies are too expensive, so it’s always best to wait for them to be available via streaming or broadcast, you can show that the ticket prices at the local independent cinema are much cheaper than at a movie theatre chain. You can then follow up by saying you can save money by bringing your own snacks.

For your uncle, who thinks spending time with family is important, you could stress how this outing will offer a fun experience for everyone to bond over.

For your cousin, who loves funny movies, you could stress that you have seen this film and think it’s great, plus well-respected critics recognize it as a ground-breaking comedy.

None of these approaches is better or worse than the others, but one might be more or less appropriate or effective for a particular audience or rhetorical situation. In all of these cases, the appeals are in play.

Aristotle proposed some labels for the major approaches regularly used to persuade audiences. Knowing these terms can make it easier for you to think and talk about the strategies you are using – and they certainly will enable you to more precisely analyze arguments made by others.

The three major strategies proposed by Aristotle are as follows.

You can make an argument based on logic.

That is, you can offer facts and evidence. Then you can explain the logic of how these facts and evidence support your position. (In the example above, you might be using logic to persuade your mom that going to the movies won’t cost as much as she thinks.)

But you can also make an argument based on emotion.

Sometimes you can get someone to act by explaining how great they will feel if they do – or how guilty they will feel if they don’t. (In the example above, connecting what you want to your uncle’s desire for family time connects to his emotions.)

You can make an argument based on credibility,

Because Aristotle lived in fourth-century BCE Athens, the terms he used – still part of the technical vocabulary of the field of rhetoric – are Greek:

Logos

Arguments that appeal primarily to an audience’s sense of logic make appeals to logos or logical appeals.

Pathos

Arguments that appeal primarily to an audience’s emotions make appeals to pathos, or emotional appeals.

Ethos

Arguments that appeal primarily to an audience’s reliance on the authority of the person delivering the argument make appeals to ethos or ethical appeals.

You don’t necessarily have to memorize these ancient Greek terms, but it’s a good idea to understand the appeals and what they do. When you do, you will be more conscious and, therefore, in control of whatever argument you are making or whatever action you want to induce.

These concepts are more complicated in practice than in theory. In real-world arguments, appeals can be quite subtle or even combined with one another in an attempt to persuade an audience. The definitions supplied above are rather simplistic. Here are some more in-depth aspects of each appeal that you might want to keep in mind.

Logos

When Aristotle wrote about appeals to logos (logical arguments), he was expressing a set of values associated with his overall worldview – that, ideally, we would only be persuaded by facts, information, and objective arguments. Logos refers to the effective use and ordering of sound reasons to support an argument. In the simplest terms, a rational argument must show more than tell; the strength of an argument is based on its proof and organization; an effective argument will be logical, which means the argument must be ordered in a fashion deemed appropriate.

To explain by way of example, rhetorician Wayne Booth (1983) famously argued that literature uses rhetorical argumentation to communicate its purposes. Readers desire completion of an argument and/or chain of events in literary and non-literary works, explains Booth, and this desire can only be fulfilled if the author has managed to effectively prove or support their storyline with good reasons. If not, then the reader will likely state that the work is silly or illogical, even if the work is set in a fantastical context in the first place (e.g. science fiction must use logos effectively to convince the reader of the story’s plausibility).

This example illustrates that logic isn’t just the domain of sciences or philosophy, but each disciplinary context or major has its own means of organizing and proving an argument. In the visual arts, a student may need to convey certain visual representations in a logical and coherent manner. In law, students may study a more classical form of logic that demands a specific order of argumentation. In Indigenous studies, students may study entirely new knowledge systems that follow the logic of Traditional Knowledge.

This is all to say there is more than one form of logic, but if pressed to provide a clear definition of logic, it’s the good reasons or premise for any action you undertake, even academic writing. The word “good” can be deceptive here, so let’s define it as the good of your community and not for selfish interests – that’s antithetical to rhetorical practice and balance. The logic of your communication involves organizing your points in a way that is both readable and suitable for the context. It means supporting those points with relevant evidence appropriate to the rhetorical situation. If you are feeling a little confused, just return to the definitions listed above.

It’s important to point out that less than scrupulous speakers or writers can create the impression of a logical argument by using the structures of logical argumentation to present highly selective or unrepresentative evidence or even unsupported claims. As someone who encounters arguments every day, you can be on the lookout for attempts to sway your thinking that are masquerading as logical arguments. Knowledge of the subject matter can help you perceive when what seems like solid claims aren’t well-supported or when what at first glance appears to be ample evidence has been cherry-picked or even falsified. And you can also be on the lookout for problems with argumentation that crop up so often they have labels. These problematic ways of making arguments are known as logical fallacies, which were introduced in the chapter “Academic Writing as Critical Thinking.”

You can probably think of examples of logical fallacies you have encountered in advertising, in political speeches, or even in conversations with friends. If logical fallacies aren’t logical, why do some writers and speakers use them? A cynical answer is that they work. More importantly, the prevalence of logical fallacies demonstrates something Aristotle recognized – that logic isn’t the only effective strategy for persuasion. Keep an eye out for these when you are scrolling through your social media feeds – can you find examples of logical fallacies? If so, you are well on your way to gaining that keen rhetorical eye that will protect you from unethical forms of argumentation.

Pathos

Aristotle advises that good rhetoricians will appeal to the emotions to stir the audience in order to create the right kind of emotional conditions, such that the audience will be persuaded of the speaker’s argument. Most rhetoricians agree that the appeal to emotions is perhaps the most dangerous of the three appeals. Audiences can be induced to actions that are detrimental to them or others. A blatant example is when political speeches brand one cultural group as a danger to another.

In Booth’s book, Now Don’t Try to Reason with Me, he outlines Neo-Aristotelian criteria for ethical use of emotional appeal (1970). Simply put, any act of communication must have a balance of ethos, pathos, and logos; otherwise, the speaker/writer misuses rhetoric. A good example of unbalanced, pathos-laden rhetoric is the smear campaigns politicians use to discredit one another. This approach yields overgeneralization and a shrill exposé, as opposed to a balanced presentation of reason, character, and emotional appeal designed to attract and influence ethical, rational, and critical readers.

Human beings are emotional and embodied beings, so it’s not surprising that their thinking can be affected by their feelings. You can probably come up with an example of when someone told you about an event in the world that aroused some emotion and consequently made you want to take action.

For example, imagine that you see your neighbour at the grocery store, and she tells you her ten-year-old daughter Mona is struggling in school ever since funding cuts led to increased class sizes. When you were Mona’s babysitter, you thought she was really bright, and she told you how much she loved school. You are upset that this kid you like a lot is having a bad experience. If the larger class size is affecting Mona negatively, you conclude, then this is a situation that can’t be allowed to continue. You decide to write to your Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) to say that schools need more funding.

In this case, you’re not being entirely logical. In fact, you could be accused of relying on anecdotal evidence or being biased or even sentimental – it is possible that every child except for Mona is thriving in larger classes. But that doesn’t automatically mean you are wrong or that your neighbour is trying to trick you. This is simply an indication that you are not investigating the information in terms of logic (logos) and credibility (ethos).

To demonstrate a positive relationship between emotions and persuasion, we can imagine a slightly different scenario. Let’s say that instead of hearing about Mona’s experience, while you were in the grocery store line, you read a news story online reporting funding cuts to local schools and resulting in larger class sizes. Later the same day, while working on a research assignment for a class, you come across a scholarly study showing that larger class sizes have a negative impact on student achievement among grade five students. These two texts might offer more reliable evidence that a problem exists, but they would probably not motivate you to take the time to write to your MLA.

Arguments that invoke an audience’s emotions in order to persuade them more effectively are said to make appeals to pathos or to use pathetic appeals. Here, “pathetic” doesn’t mean something you should feel sorry for because it’s inadequate – rather, it just means having to do with emotions. And there can be a variety of emotions brought up by pathetic appeals.

The most obvious appeals to pathos arouse big, clear emotions. For example, an advertisement by a charitable organization that helps to feed hungry children might prominently present a photo of a malnourished, crying infant. That image would likely make audiences feel a strong sense of sadness, pity, and perhaps even guilt – emotions that might more directly lead someone to make a donation than would a page full of statistics about the number of children affected by food shortages.

Politicians can win over voters by presenting thoughtful, detailed plans – but they can also get supporters to act by invoking fear or anger. It is not logical or ethical to say that an opponent’s plan to pilot a restorative justice program for juvenile offenders will lead to senior citizens being murdered in their beds, but offering up such a frightening possibility stirs up strong feelings.

But note that appeals to pathos can be much more subtle. A company that presents its product in a humorous advertisement is getting the audience to associate the product with laughter and a positive feeling. A politician who tells a story about a hometown hockey player who made it to the big leagues elicits civic pride, a feeling that could motivate someone to make a donation or volunteer for a campaign. And even subtle language choices can make appeals to pathos – the authors of this textbook use “we” constructions a lot to try to invoke a sense of belonging in readers. This use of “we” is a rhetorical strategy to connect with our readers in order to further our goal to persuade them (you) to see academic writing as an important and interesting subject.

Academic writing tends to emphasize appeals to logos, but that doesn’t mean there are no appeals to pathos present. When you read an academic article, note places where the authors use “we” constructions or otherwise attempt to build a sense of community for readers. See if the writers have included jokes or witty turns of phrase. And especially watch for case studies or examples that evoke strong emotions, situated within the context of well-supported, highly logical arguments.

As you craft your own arguments, it’s worth reflecting on when it might actually be inappropriate to avoid appeals to emotion in an effort to seem scholarly and authoritative. Some subjects arouse strong emotions in people for very good reasons, and an entirely logical argument about those subjects will likely bore or irritate your readers.

Ethos

The appeal to ethos might appear to be the least logical of all persuasive strategies. Ethical appeals (appeals to ethos) rely on the authority or character of the speaker or writer. That is, an audience is more likely to be persuaded by the same argument being presented by one speaker rather than another. An ad hominem attack (which was identified above as an example of a logical fallacy) is an attack on a writer’s ethos rather than on their argument and thus isn’t logical – but proving that a writer is a habitual liar will make it more difficult to believe that person’s evidence and claims are correct.

Because it can be difficult to distinguish between when an argument is truly logical or merely appears logical, and because emotions regularly influence thinking, Aristotle and other early rhetorical theorists pointed to ethos as a safeguard against problematic arguments. Roman rhetorician Quintillian actually defined an effective argument as involving “A good man speaking well.” Why a good man? In the ancient world, an audience would know the public reputation and maybe the private actions of the individual speaking in a law court or the Senate (a person who would certainly be male), and the audience could reasonably assume a person they know to be of good character – known to be smart or just or level-headed – would probably make an argument that is in the public interest. And this context is part of why the rhetorical triangle identifies the speaker (or writer) as one of the key elements in any act of communication.

The identity of a speaker or writer still affects how persuasive a text will be for its intended audience. You likely hope a politician is true to their word. If they aren’t, then you probably won’t respond to their fundraising letter with a donation. You probably should be skeptical of speeches about getting “tough on crime” made by a politician who was recently involved in a bribery scandal. They lack credibility. Most of the time, you are assessing others’ credibility. Perhaps a friend who boasts about a Fortnight win streak but then doesn’t show that same skill when you are playing with them loses credibility. Perhaps you win a scholarship, which increases your credibility in the eyes of university admissions. But what about academic writing?

In academic writing, ethos more commonly involves our sense of whether the writer is an authority on the subject being discussed, more so than whether the writer is “a good man.” When you read a peer-reviewed journal article written by an award-winning scientist who works at a prestigious university, it is reasonable to believe this person has the knowledge and expertise to make a good argument. For example, if an epidemiologist who teaches at the University of Toronto’s medical school writes that wearing masks decreases the spread of COVID-19, this argument seems worthy of consideration.

In contrast, when you get advice from a public figure, a corporation, or someone’s uncle’s neighbour’s tweet that gargling with hydrogen peroxide keeps individuals from contracting COVID-19, you should probably reflect on how much they know about the subject. Put another way, a celebrity might have the expertise to tell you how to make a delicious green smoothie, but that same person isn’t credible as an authority to claim that drinking two green smoothies a day will keep individuals from catching any particular disease.

While our sense of a speaker or writer’s authority can be a good way to begin distinguishing between truthful and highly problematic arguments, appeals to ethos can also lead us astray. For instance, because people tend to believe doctors have a lot of medical knowledge and strongly value their patients’ health, an individual doctor who endorses a treatment might be able to persuade a lot of people to try it. But an individual doctor can be unethical – say, motivated by the financial benefit of recommending a treatment their office happens to offer for a fee. The term “conman” is a contraction of “confidence man,” and people in whom we have confidence have the power to swindle or trick us.

And even when people aren’t trying to deceive, ethos can be problematically linked to stereotypes and even prejudice. Numerous studies of class evaluations of college and university courses show that students are inclined to perceive (white) male professors to be knowledgeable and authoritative. At the same time, they are more likely to describe female professors (particularly Black women, women of colour and Indigenous women) as incompetent and lacking expertise (Bavishi, Madera, & Hebl, 2010; Boring, 2017; Centra & Gaubatz, 2000). This trend might be explained by the cultural assumption that the stereotypical university professor is white and male, while the stereotypical K-12 teacher is female (Wong, 2019).

There’s no reason why professors of differing races, genders, and sexualities with the same educational experience and job experience should be seen as differently authoritative, but this dynamic is common.

In some situations, young people can be perceived as lacking the life experience necessary to have an informed opinion about issues that directly affect their lives. A speaker or writer’s various identity categories (including an individual’s sexuality, race, gender, socio-economic background, ethnicity, and/or religion) can lead audience members to perceive that person as too ill-informed or too biased to make a reasonable argument. Appeals to ethos are not always made on a level playing field.

That said, there are some important ways in which appeals to ethos are in the control of a speaker or writer. Following the conventions of the genre in which one is communicating implies that a writer belongs to the same community as the audience and thus is worth listening to. Note that this dynamic helps to explain why many teachers harp on spelling and punctuation errors in student writing – they perceive, rightly or wrongly, that these sorts of mistakes damage the writer’s scholarly ethos since one of the conventions of academic essays is adherence to a set of language rules. Through stylistic choices and selection of compelling evidence, a writer can create the impression of themselves as smart, well-informed, or even witty, which are qualities that will make an audience more likely to believe their conclusions.

Most notably, writers can make strong appeals to ethos in some situations by sharing their personal experiences. A student who is a member of the Songhees Nation and grew up on Songhees territory has more authority to speak about the need for reform in the local educational system than a professor of education with a PhD from Oxford University who works at the University of Saskatchewan. Our own identities, backgrounds, and histories aren’t always directly relevant to the subject matter of an academic essay, but if you can bring yourself explicitly into your writing, then you have an opportunity to make very strong appeals to ethos.

Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation

A modern model of argumentation, developed by philosopher Stephen Toulmin, helps us further analyze and build academic arguments. Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation provides a structured framework for analyzing and building arguments and helps both writers and readers understand how an argument works or doesn’t work.

Toulmin (1922-2009) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. He devoted his work to analyzing moral reasoning and sought to develop practical methods for evaluating ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments, particularly academic arguments.

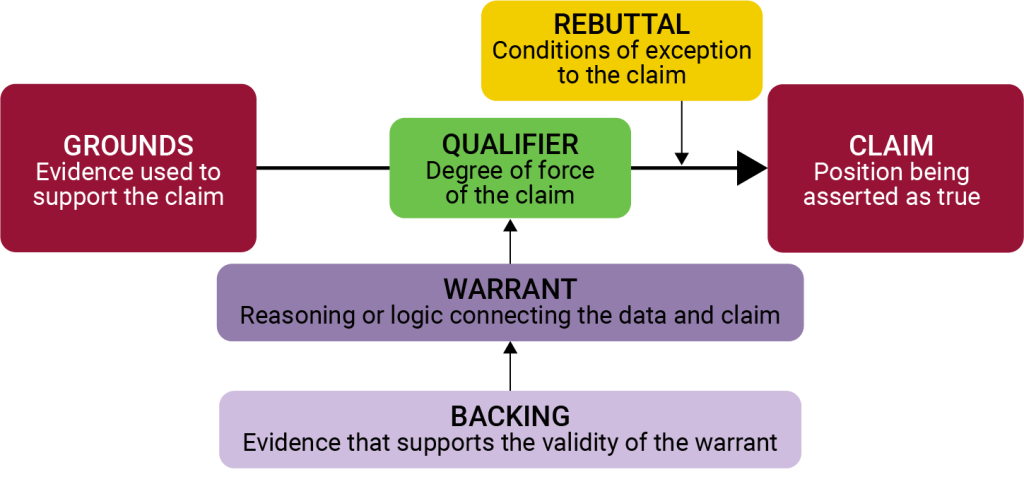

The six components of the Toulmin Model of Argumentation are a claim, grounds, warrant, backing, qualifier, and rebuttal, as illustrated in Figure 1. These components of argumentation are explained in more detail below.

Claim

The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. Here’s an example of a claim:

- My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and a warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

Grounds

The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and include the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support. The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

- Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

- Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

Warrant

A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

- A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements, including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos, ethos or pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This allows the other person to question and challenge the warrant, perhaps to demonstrate that it is weak or unfounded.

Backing

The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: Grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

- Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

Qualifier

The qualifier indicates how the data supports the warrant and may limit the claim’s universality. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (e.g., all women want to be mothers) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

- Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

- Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do not harm the ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained from making false claims. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

Rebuttal

Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

- There is a support desk that handles technical issues.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using a strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used to analyze arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Conclusion

Understanding and applying Aristotle’s rhetorical appeals and Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation will help you build an important set of skills as an academic writer, as a central purpose of academic writing is to convince your readers of the importance of your ideas or research.

References

Bavishi, A., Madera, J. M., & Hebl, M. R. (2010). The effect of professor ethnicity and gender on student evaluations: Judged before met. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 3(4), 245-256. dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/10.1037/a0020763

Booth, W. C. (1970). Now don’t try to reason with me: Essays and ironies for a credulous age. University of Chicago Press.

Booth, W. C. (1983). The rhetoric of fiction. University of Chicago Press.

Boring, A. (2017). Gender biases in student evaluations of teaching. Journal of Public Economics, 145, 27-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2016.11.006

Centra, J. A., & Gaubatz, N. B. (2000). Is there gender bias in student evaluations of teaching?. The Journal of Higher Education, 71(1), 17-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2000.11780814

Ramage, J., & Callaway, M., Clary-Lemon, J., & Waggoner, Z. (2009). Argument in composition. Parlor Press LLC. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/referenceguides/ramage-argument/

Wong, A. (2019, February 20). The U.S. teaching population is getting bigger and more female. The Atlantic. theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/02/the-explosion-of-women-teachers/582622/

Attributions

“Academic Writing as Persuasion” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted from:

- “3.5 Everything’s Persuasion” by Erin Kelly; Sara Humphreys; Nancy Ami; and Natalie Boldt, Why Write? A Guide for Students in Canada 2nd Edition is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- “63 Toulmin Argument Model” by Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd, Write What Matters is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0