Section 1: Why Do We Write?

Writing Conventions: What Are They and Why Do They Matter?

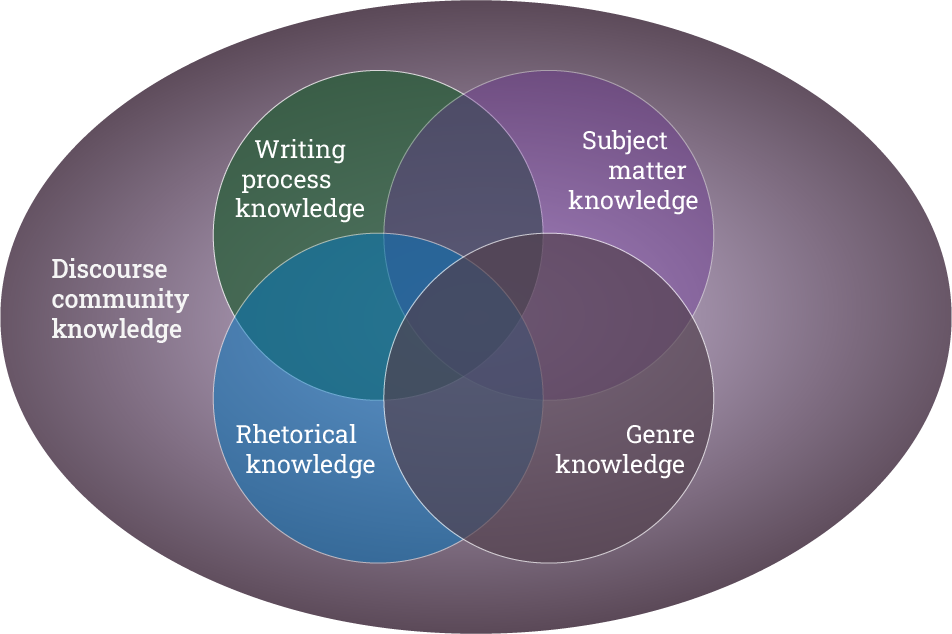

In the chapter “Developing a Growth Mindset with Respect to Writing,” you learned that writing involves multiple abilities and types of knowledge, which are represented in Anne Beaufort’s model of writing expertise (See Figure 1). The model identifies five areas where writers must develop their competence:

- Writing process knowledge

- Subject matter knowledge

- Genre knowledge

- Rhetorical knowledge, and

- Discourse community knowledge.

In this chapter, we will focus on genre knowledge and what developing this type of knowledge entails. Genres (types of text) are built on writing conventions (socially approved patterns in writing) that help us communicate effectively. When we learn to write genres like the five-paragraph essay, we learn what content is appropriate, how to arrange the content, and what language conventions we should follow in that genre. Language conventions that writers must follow often fall under the broad categories of grammar and style. Another important writing convention, especially for academic writing, is citation. This chapter will teach you more about genre, grammar, style, and citation and why these conventions matter.

Note. Adapted from “College writing and beyond: A new framework for university writing instruction” by A. Beaufort, 2007.

What are Genres?

Genres are sets of texts that share common characteristics. In the past, we thought of genres only in literary contexts. For instance, you likely discuss different genres, such as poems, short stories, and novels, in your English classes. However, in the late twentieth century, writing studies scholars started studying other types of workplace and academic genres, such as resumés, emails, lab reports, and academic research papers. These scholars developed important insight into how genres are created and evolve and how learning about genres can help writers.

How genres are created and how they evolve

Genres are textual patterns that develop over time to help people communicate in social situations that they encounter repeatedly. To show how genres are created to serve a particular social purpose, let’s look at the history of a genre you are familiar with: the five-paragraph essay or theme (theme is the word used for school essays).

According to rhetoric and composition scholar Matthew Nunes (2013), the five-paragraph theme grew from a historical link between the study of rhetoric (the art of persuasive communication) and writing instruction. The systematic study of rhetoric was developed by Ancient Greeks and Romans, as they were interested in how public speakers could write and deliver speeches to persuade their fellow citizens. After the printing press was introduced in the fifteenth century CE in Europe, reading and writing became more common, and the techniques used to teach public speaking were adopted to teach writing. From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century CE, students wrote practice essays (themes) based on the five or six parts of discourse identified by a prominent Roman speaker named Cicero (Nunes, 2013). You will likely recognize these parts as they are similar to what you have learned about how to structure a five-paragraph essay:

- Exordium (Introduction and hook to capture the reader’s attention)

- Narratio (Background and context for an argument)

- Partido (Outline of the major points the argument will address)

- Confirmatio (Points supporting an argument)

- Refutatio (Break down and refutation of an opposing argument)

- Peroratio (Conclusion, summary of the strongest points, and call to action)

The five-paragraph essay settled into its current format in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the nineteenth century, writing instructors at American universities such as Harvard asked their students to write daily essays using the variations of Cicero’s rhetorical structure described above (Tremmel, 2011). In 1959, an article by Victor Pudlowksi (1959), a high school English teacher, used the name “five-paragraph paper” and described all of the elements of this genre in detail. Pudlowski’s description of the five-paragraph essay is very prescriptive, which means that it specifies the precise elements that students should include in the five-paragraph essay. This emphasis on the structure of writing was linked to a particular approach to writing instruction that was common throughout the twentieth century. Writing studies scholars call this the “current-traditional” approach to teaching writing (Berlin, 1987).

It might surprise you to learn that many contemporary writing studies scholars are now advocating against the teaching of five-paragraph essays in schools. These scholars argue that this form of writing does not prepare modern students for the many different genres of writing that they will encounter in their lives and its restrictive form kills many students’ passion for writing. You will likely experience the limitations of the five-paragraph essay as you are confronted with the new genres you have to learn for university. At university, you will now encounter genres such as lab reports, literature reviews, research papers, metacognitive reflections, and analytical essays. It is not clear how well the five-paragraph essay prepares you to adapt your writing for new contexts, such as university writing and workplace writing.

Now that you know a little bit about the history of the five-paragraph essay, let’s consider how the creation and evolution of this genre were tied to repeated social situations.

- As systems of government evolved in Ancient Greece and Rome, so too did the need to persuade groups of other people. The Ancient Greeks and Romans recognized which patterns of persuasion were the most effective. These patterns were repeated by speakers and were taught to other speakers. Audiences came to expect these patterns, and the patterns helped them understand the speaker’s argument. Important Greek and Roman thinkers like Aristotle and Cicero wrote down their analyses of these genres, which were transmitted to future writing instructors through the teaching of speech.

- As human literacy increased, so too did the need for standardized reading and writing instruction. We needed to find ways to teach writing to an increasing number of students. Having a standard form to teach students helped to assess students more effectively across many contexts. In addition, the five-paragraph essay is a good training genre as it involves important moves such as stating a main claim and supporting it with evidence.

- In the twenty-first century, humans write more than ever. We write texts, social media posts, emails, reports, essays, presentations, and many other genres. We are now reconsidering whether teaching one standard genre of writing is the best approach for modern students. Our communicative needs are changing, and therefore, the genres we use and teach are also changing. The genre of the five-paragraph essay may adapt to this new reality, or it might be abandoned.

If you understand the purpose that a written genre serves and how it is connected to the social situations in which it is used, you can use this insight when you are learning a new genre. For instance, now that you know that the five-paragraph essay is exclusively a school genre and not the only genre of writing in university, you might start to ask yourself important questions about the new genres you encounter. You can ask yourself:

- What purpose does this genre serve?

- How is this genre’s purpose tied to a repeated social situation?

- What are the main features of this genre, and how do they help the genre achieve its purpose?

As you become experienced writers, you might also start to ask if a genre still achieves its original purpose. If it doesn’t, you and other writers may start to introduce changes that help the genre respond to a new context and purpose.

What are Grammar and Style?

Two other important writing conventions are grammar and style.

You probably know grammar as rules that writers and speakers use to communicate correctly. Many students have had a bad experience when they have violated one of those rules. They recount how they felt badly when they received their writing back, covered with red marks indicating all of their grammatical mistakes.

You may be less familiar with the concept of style. When writers use style rules or guidelines, they knowingly apply linguistic strategies to improve the impact of their text. For instance, a style guide might tell you to use specific verbs like “argues” or “implies” rather than generic verbs like “says.” All options are grammatical, but “argues” and “implies” gives the reader more information about the action.

There are other sets of rules and guidelines that we apply when we write, and it is helpful to understand these nuances. Patrick Hartwell, a writing studies scholar, identifies five different types of grammar that distinguish how rules govern language use (1985). The first three types of grammar are not ones that we learn in school. We learn them through the process of learning a language, either as a child or without school learning or through the scientific study of language. The last two types of grammar are the ones we learn in school.

Here are the five types of grammar identified by Hartwell (1985).

Grammar 1

This is the grammar that we don’t have to learn explicitly. These are the rules that all of the speakers of a language share. For instance, in English, we put adjectives before nouns, such as in the phrase “the brown cat.” It is incorrect in English to say “the cat brown.” If English is your first language, you don’t have to be told this. You just learned this rule when you learned to speak English.

Grammar 2

Grammar 3

Grammar 4

Grammar 4 includes the prescriptive rules that we learn when we are learning to write at school. For instance, you may have been told that you shouldn’t begin a sentence with “and” or “but” or that you shouldn’t end a sentence with a preposition such as “in,” “with,” or “for.”

Many of these prescriptive rules are arbitrary, meaning that someone made them up to advocate for a desired form of English that was not reflective of how the language was used. For example, you may have heard the rule that you should not split infinitives in English: This rule states you should write “to go boldly” rather than “to boldly go.” This rule first appeared in the nineteenth century and is likely the result of prescriptive grammarians applying rules from Latin to English; however, there are many examples of split infinitives in well-respected English writing before and after the pronouncement of this rule (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

The rules about not starting a sentence with “and” or “but” are also arbitrary, and they are not consistently applied across all types of writing. Many sentences in published sources start with an “and” or a “but.” Your teachers likely told you these rules to help you avoid writing incomplete sentences.

The prescriptive rule about not ending a sentence in a preposition has mostly fallen out of favour; it, too, was a rule from Latin that was applied to English (Bowman, 2024). So, yes, you can end a sentence with a preposition in English.

Grammar 5

Grammar 5 is also taught in school and involves consciously using particular strategies to achieve effects with your writing. Grammar 5 is about style. Style rules or guidelines are also arbitrary, but they are developed to improve the effectiveness of writing. For example, you might receive feedback that you should eliminate all redundant words in your sentences. If you have the phrase “full and complete,” you should eliminate one of the adjectives because you don’t need both to convey your meaning. “Full and complete” is grammatically correct, but eliminating the redundancy makes your writing more effective.

Large organizations will often develop their own style guide to help writers make consistent choices. For instance, the Government of Canada has a web writing style guide for writers in their organization to use when they are writing web content.

Grammar is the language that makes it possible for us to talk about language

All five types of grammar are at play when you write a text. Pause here and reflect upon the amazing complexity of language and writing. It is no wonder that writing bedevils us at times! However, as writers, we need to identify and understand the different types of grammar. The National Council of Teachers of English (2002) reminds us, “Grammar is important because it is the language that makes it possible for us to talk about language.” We need to have a common vocabulary about the standards and conventions of writing to learn how to communicate more effectively.

Generally, you will follow the rules of Grammars 1, 2, and 3 without effort, particularly if you are a native speaker of a language. You learn these rules when you acquire a language. Grammars 4 and 5 are more difficult to master. They require awareness and learning. While the rules of Grammars 4 and 5 are arbitrary, they are meaningful to many readers. You may be judged harshly if you violate these rules. In other words, learning and applying the rules your readers care about will make your writing more effective. Your reader is more likely to accept your writing if it conforms to their expectations.

Remember one important thing about all types of grammar rules: They change. Language is a living tool for human communication, and it changes as we change. The rules you use now for writing will not be the rules you use in the future.

What is Citation?

Citation is a writing convention specific to academic writing. Citation styles are developed by academic organizations like the Modern Language Association or the Council of Science Editors to standardize how a writer should indicate to a reader that an idea is not their own and where that idea appeared originally. This writing convention is important in academic writing because the academic community values the connection between ideas and the ability to verify the quality of knowledge that is shared.

We will discuss citation more in-depth in the chapter “Academic Writing as Conversation.”

Additional Resources

The video “Does Grammar Matter” (4:38) by Andreea S. Calude provides a good overview of different approaches to grammar.

The Oregon State Guide to Grammar is a series of videos on important grammar topics.

References

Beaufort, A. (2007). College writing and beyond: A new framework for university writing instruction. Utah State Press.

Berlin, J. A. (1987). Rhetoric and reality: Writing instruction in American colleges, 1900-1985. Southern Illinois University Press.

Bowman, E. (2024, March 1). Merriam-Webster says you can end a sentence with a preposition. The internet goes off. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/27/1233663125/grammar-preposition-sentence-rule-myth-merriam-webster-dictionary

Government of Canada. (2024). Canada.ca Content Style Guide. Canada.ca. https://design.canada.ca/style-guide/

Hartwell, P. (1985). Grammar, grammars, and the teaching of grammar. College English, 47(2), 105-127. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce198513293

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). To boldly go: Star Trek and the split infinitive. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/to-boldly-split-infinitives

National Council of the Teachers of English. (2002). Some questions and answers about grammar. [NCTE] National Council of the Teachers of English. https://ncte.org/statement/qandaaboutgrammar/

Nunes, M. J. (2013). The five-paragraph essay: Its evolution and roots in theme-writing. Rhetoric Review, 32(3), 295–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350198.2013.797877

Pudlowski, V. (1959). Compositions-write’em right!. English Journal, 48(9), 535-537. https://www.jstor.org/stable/808855

Tremmel, M. (2011). What to make of the five-paragraph theme: History of the genre and implications. Teaching English in the two-year college, 39(1), 29-42.

Attributions

“Writing Conventions: What Are They and Why Do They Matter?” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0