Section 5: Important Moves in Academic Writing

Editing for Cohesion

What is Cohesion?

When we talk about cohesion in writing, we are talking about how your sentences flow together. In cohesive writing, the writer considers the relationship between all their sentences and employs strategies to make the relationship between sentences clear to the reader. Reading cohesive writing is a smooth journey for readers, but reading writing where there is no flow between sentences is a bumpy ride, requiring the reader to expend extra effort to understand the relationship between ideas.

Let’s look at a few examples. Read the following sets of sentences. Which sets of sentences do you feel flow better?

Set 1

-

- The experiment failed to produce significant results. Consequently, the researchers decided to redesign the study.

- The experiment failed to produce significant results. The researchers decided to redesign the study.

Set 2

-

- The government released new climate targets. The targets were criticized by environmental groups.

- The government released new climate targets. This announcement was criticized by environmental groups.

Set 3

-

- The city unveiled a new bike lane along Main Street. Cyclists say the design makes their commute faster and safer.

- The city unveiled a new bike lane along Main Street. The new design, cyclists say, makes their commute faster and safer.

You likely found that Example A flowed better than Example B in Set 1, Example B flowed better than Example A in Set 2, and Example B flowed better than Example A in Set 3. These examples demonstrate three techniques for improving the flow between sentences:

- Using transitional words and phrases

- Using pronouns

- Using the given-new principle

The following sections will describe these strategies in detail.

Using Transitional Words and Phrases

Transitional words or phrases typically appear at the beginning of a sentence, and they help to specify the relationship between two sentences. Let’s look at the sentences you read above more closely.

-

- The experiment failed to produce significant results. Consequently, the researchers decided to redesign the study.

- The experiment failed to produce significant results. The researchers decided to redesign the study.

In this set of sentences, Example A uses the transitional word “consequently.” This additional word helps clarify the relationship between the first and second sentences by indicating to the reader that the action in the second sentence occurred as a result of the action in the first sentence. This additional word adds cohesion to the sentence pair and helps the reader understand the writer’s meaning more clearly.

You may have learned the basic transitional words or phrases in Table 1. These can be effective when writing simple information in a structure where you simply add one idea after another, or want to show the order of events.

| first

second third last moreover |

firstly

secondly thirdly last but not least, furthermore |

first of all

next then finally besides |

Table 1. A list of commonly used transitional words and phrases

However, more complex university-level writing requires more sophisticated transitions. It requires you to connect ideas in ways that show the logic of why one idea comes after another in a complex argument or analysis. For example, you might be comparing/contrasting ideas, or showing a cause and effect relationship, providing detailed examples to illustrate an idea, or presenting a conclusion to an argument. When expressing these complex ideas, the simple transitions you’ve learned earlier will not always be effective – indeed, they may even confuse the reader.

Consider the transitions in Table 2 and how they are categorized. While this is not an exhaustive list, it will give you a sense of the many transitional words and phrases that you can choose from, and demonstrate the need to choose the one that most effectively conveys your meaning.

| Addition | Comparison | Contrast | Cause and Effect |

| also

and in addition in fact indeed so too as well as furthermore moreover |

along the same lines

in the same way similarly likewise like |

although

but in contrast conversely despite even though however nevertheless whereas yet while on the other hand |

accordingly

as a result consequently hence it follows, then since so then therefore thus |

| Conclusion | Example | Concession | Elaboration |

| as a result

consequently hence in conclusion in short in sum it follow, then so therefore thus |

as an illustration

consider for example for instance specifically a case in point |

admittedly

granted of course naturally to be sure conceding that although it is true that… |

admittedly

granted of course naturally to be sure conceding that although it is true that… by extension in short that is to say in other words to put it another way to put it bluntly to put it succinctly ultimately |

Table 2. A list of more sophisticated transition words and phrases to use in university writing

Transitional words and phrases show the connection between ideas and show how one idea relates to and builds upon another. They help create coherence. When transitions are missing or inappropriate, the reader struggles to follow the logic and development of ideas. The most effective transitions are sometimes invisible; they rely on the vocabulary and logic of your sentence to allow the reader to “connect the dots” and see the logical flow of your discussion.

Using Pronouns

Using pronouns–words that stand in for a noun previously mentioned (also called the antecedent)–can also help to build cohesion or flow between sentences. Let’s look at the second set of sentences from the introduction to this chapter again.

-

- The government released new climate targets. The targets were criticized by environmental groups.

- The government released new climate targets. This announcement was criticized by environmental groups.

The second sentence starts with “this” (also known as a demonstrative pronoun) and “announcement.” The use of “this” here helps the reader to understand that “announcement” refers to the action in the previous sentence. This builds cohesion.

Here’s another example, where personal pronouns help to build cohesion.

-

- The researchers completed the experiment. The researchers published the results in a major journal.

- The researchers completed the experiment. They published their results in a major journal.

Here, the pronouns “they” and “their” help to build a relationship between the two sentences.

While using pronouns can be a powerful cohesion-building strategy, you have to be careful. Using pronouns can also introduce confusion. Consider the following sentence sets.

-

- The supervisor praised Jordan after the meeting. The supervisor asked Alex to revise the report.

- The supervisor praised Jordan after the meeting. He asked him to revise the report.

In Example B, it is not clear to whom “he” and “him” refer. Using pronouns in this case resulted in an ambiguous reference.

When using pronouns, you should also be sure that the antecedent (the noun to which the pronoun refers) is not too far away. For example, in the following passage, the pronoun “it” in the final sentence is unclear because we do not know which pronoun “it” refers to because the pronoun is too distant from its antecedent “the study.”

Dr. Li published a groundbreaking study on coral bleaching and its relationship to ocean acidification. The study received widespread media attention, and several research institutions cited its findings. Dr. Li was honoured at an international panel on climate change. It contributed to greater public awareness about the issue of coral bleaching.

Finally, be careful when you use the demonstrative pronoun “this.” It is generally better to use “this” with a noun, rather than on its own. Have a look at the following passage. Can you determine what the “this” refers to?

Riley gathered survey data from over 500 participants, analyzing their responses to questions on workplace communication. After creating charts and identifying patterns in the data, Riley began drafting a report. Several peer reviewers commented on the clarity of the visuals. This helped guide the final edits.

The final sentence would be improved by the inclusion of a specific noun. For example, revising the final sentence to “These comments helped guide the final drafts” would help to clarify the relationship between the last sentence and the previous one.

Using the Given-New Principle

Another strategy to improve the cohesion of your writing is to use the given-new principle. The given-new principle refers to a common, but often overlooked, pattern in how we present information in our sentences in English. In English, we like to present old or given information that the reader is likely to know in the first part of a sentence and to add new information that the reader is unlikely to know at the end of the sentence. We can use this principle to build links between sentences.

Let’s look at how this principle is at work in the examples at the beginning of this chapter.

-

- The city unveiled a new bike lane along Main Street. Cyclists say the design makes their commute faster and safer.

- The city unveiled a new bike lane along Main Street. The new design, cyclists say, makes their commute faster and safer.

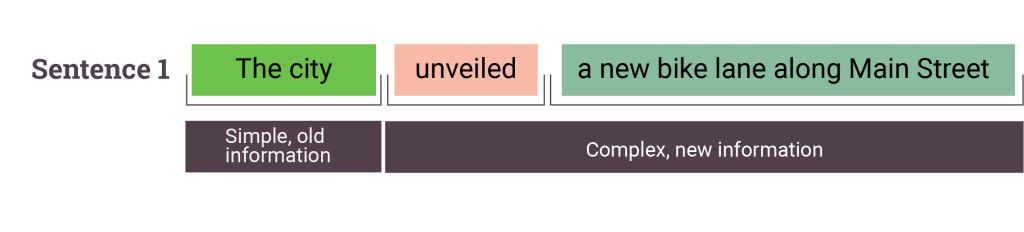

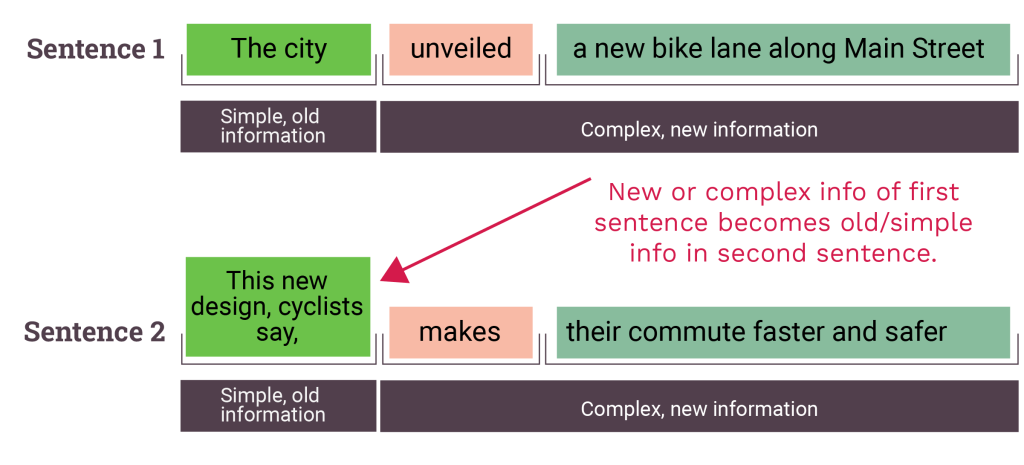

Example B uses the given-new principle, whereas Example A does not. This is how it works. In sentence 1, we can assume the old or given information is “The city.” The new information is “unveiled a new bike lane along Main Street.” See Figure 1 for a diagram of this sentence.

Sentence 2 flows better with Sentence 1 if we start by repeating the information provided as new information in Sentence 1. The new information provided in Sentence 1 becomes the given information in Sentence 2. By moving “this new design” to the beginning of Sentence 2, we have created a chain of two sentences using the given-new principle. The second sentence uses the new information in the first sentence as its given information. This creates flow between sentences and helps the reader to parse the meaning more clearly. See Figure 2 for a diagram of the chain of information created by using the given-new principle.

While it isn’t always possible to build given-new chains across sentences, it is a strategy that has a lot of impact when you do use it. It can turn clunky writing into polished and professional writing quickly.

Attributions

“Editing for Cohesion” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and includes material adapted from:

- “APPENDICES: Academic Writing Basics” by Suzan Last, Technical Writing Essentials is licensed under CC BY 4.0