Section 5: Important Moves in Academic Writing

Using Visuals to Communicate

Introduction

It may be a cliché to say, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” but visual images have power. Good communication, even academic communication, is a multisensory experience. Children first learning how to read often gravitate toward books with engaging pictures. As adults, we progress to denser books without pictures, yet we still visualize ideas to help us comprehend the text. Advertisers favour visual media—television, magazines, and billboards—because they are the best way to hook an audience. Websites rely on colour, graphics, icons, and a clear system of visual organization to engage Internet surfers. Visuals bring ideas to life for many readers and audiences in multiple ways:

- As a link between raw data and usable knowledge

- To provide concrete, vivid, and quick representations

- To save space

- To speak in a universal language

- To be persuasive (Picardi, 2001)

When Should You Use a Visual?

Academic writers include visuals in their texts for the following reasons:

Representational

These visuals physically represent or resemble objects or actions in the text and are relevant to the content of the text. For example, rather than giving a detailed textual description of a new playground, you might include an image or render of the new playground and use the text to highlight specific features or information.

Analogical

Analogical visuals are used to compare and contrast two things and explain their likeness or correspondence. For example, a marketing textbook author might clarify the difference between targeted marketing and mass marketing by including images of a single fisherman with a single fishing rod and line next to an image of a bigger boat with a fishing net. By using the fishing analogy, the marketing textbook author is attempting to connect possible prior understanding of the audience, a visual, and the concepts of targeted marketing versus mass marketing.

Organizational

The purpose of organizational images is to provide structure to information, visually define relationships, and illustrate connections. A chart of the hierarchical structure of a company is one example of an organizational image.

Note that academic writers do not typically use visuals to decorate their texts, as this may distract from the meaning they are trying to convey.

Types of Visuals

Visuals in academic writing are typically referred to as figures. Figures can include the following types of visuals:

- Symbols

- Maps

- Graphs and tables

- Diagrams

- Illustrations

- Photos

We will describe these in more detail below.

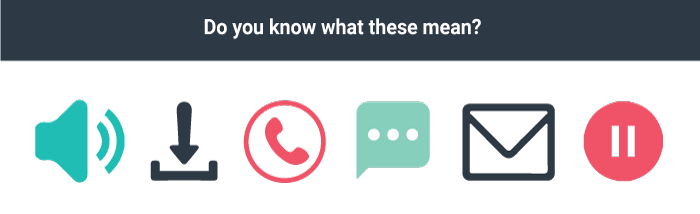

Symbols

Symbols include a range of items that can be either pictographic or abstract. We are surrounded by symbols, but how often do you think about the symbols that communicate with you daily? What symbols can you see right now in your surroundings? The icons for the apps on your phone are familiar symbols to you. How about the TV remote control, which uses symbols to indicate the function of its buttons. Company logos lead you to identify the brand before you even read any words. Or look at the tags on your clothing; they use symbols to tell you how to wash and dry the garments as intended.

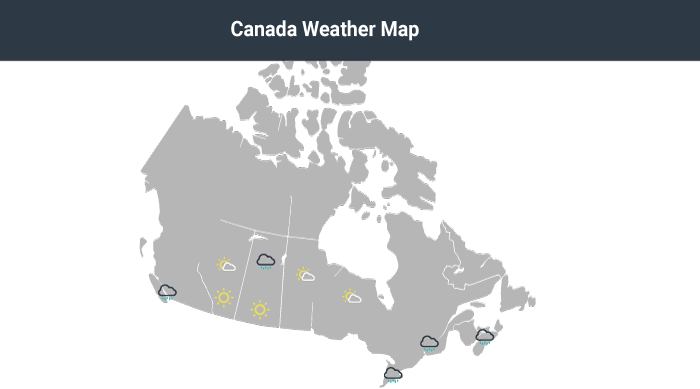

Maps

Maps sometimes include map charts or statistical maps. Maps are often used to communicate geographical and other information in one visual (Picardi, 2001).

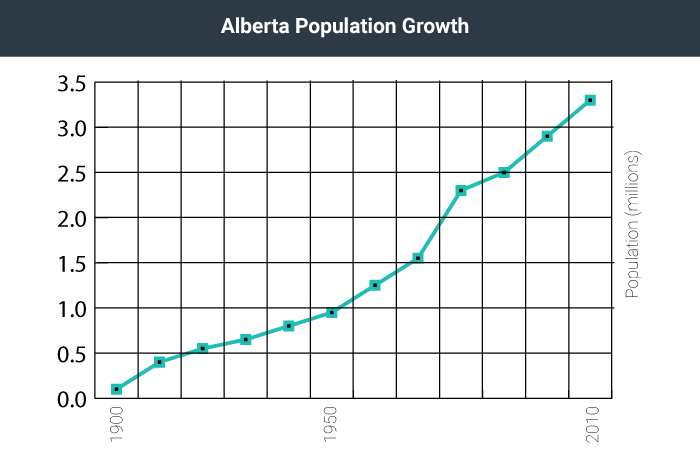

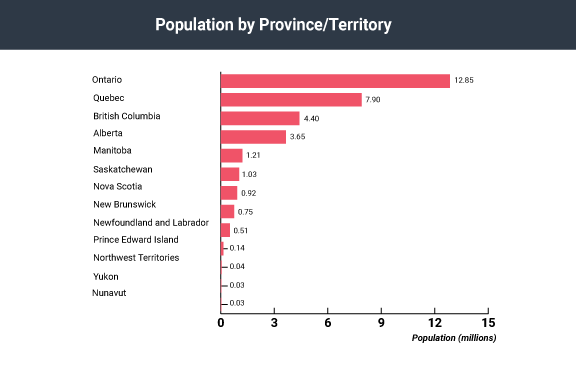

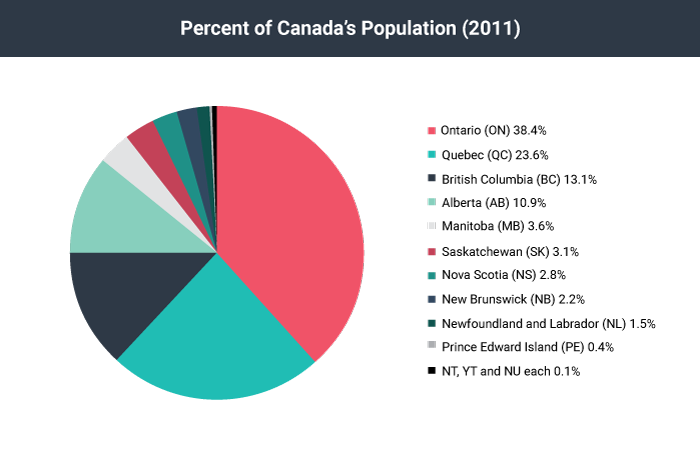

Graphs and Tables

Graphs can take various forms, the most common being line graphs, bar graphs, and pie charts. Each type is better suited to different situations and purposes. For example, line graphs show change quickly, while bar charts are effective to compare data, and pie charts visualize the relation between parts and the whole (Picardi, 2001). Tables can be more effective for arguments that include qualitative data (not just numbers).

Tip

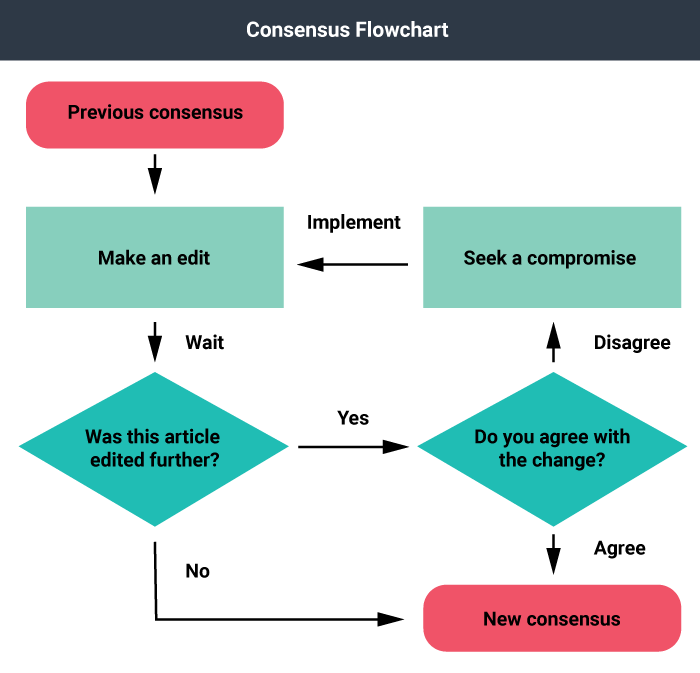

Diagrams

Saunders (1994) describes diagrams as “visuals drawn to represent and identify parts of a whole, a process, a general scheme, and/or the flow of results of an action or process.” One example of a diagram would be a flow chart. Flow charts are often used to show physical processes, such as in a manufacturing facility, or in the decision-making procedures of a larger corporation, for example. Flow charts combine the use of text, colour, and shapes to indicate various functions performed in a process.

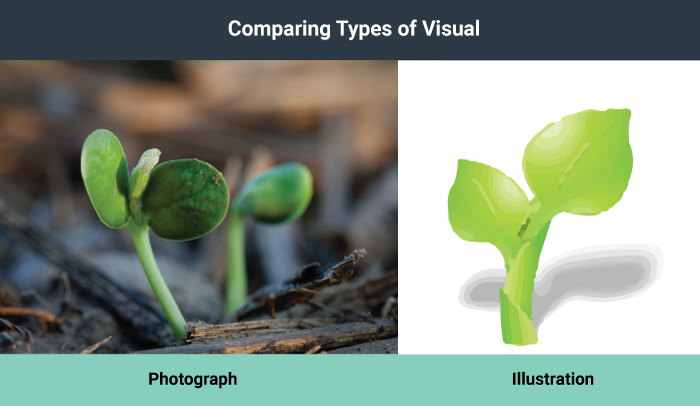

Photographs

Photographs (still or moving) depict concrete objects, tell a story, provide a scenario, and persuade an audience.

Illustrations

Illustrations can be realistic or abstract. There are instances where a photograph may be too rich in visual elements, and a simpler line drawing communicates more quickly and clearly. For example, next time you are in a public building, look around for the fire escape plan. Is it a photograph or a line drawing? Illustrations offer a simpler visual and can be easier to understand than photographs because they filter out unnecessary information.

Choosing a Type of Visual

There are many considerations to keep in mind when choosing visuals. Remember that any visuals you use should enhance the content of the text. For example, only add photos if viewing the photos will clarify the text. Near each visual, explain its purpose concisely using a caption, and refer to your visual explicitly in your text. Do not expect your readers to figure out the importance of the visuals on their own.

The following table summarizes the visuals you might choose based on your communication purpose.

| Communication Purpose | Appropriate Visuals |

|---|---|

| Depict an object | Photo, 3D Model, Illustration |

| Persuade an audience | Photo, Illustration, Chart |

| Demonstrate a procedure | Photo, Illustration, Flowchart |

| Explain a process | Diagram, Symbol, Illustration |

| Make comparisons | Bar graph, Line graph, Table |

| Demonstrate trends or data | Line graph |

| Organize information | Organize information Map, Table |

Table 1. Communication purpose and appropriate choice of visual

Finding and Crediting Visuals

You have three choices for finding visuals to use in your work. You can search the Internet, use photos you have taken, or create images yourself.

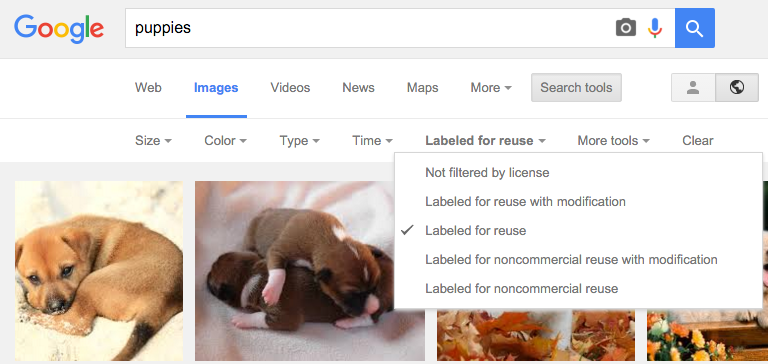

Finding visuals online

The Internet is a powerful tool you can use to find visuals to complement your work. If you simply click on “images” for your topic in a search engine, you will generate royalty-free and copyright-protected images. However, if you include a term such as stock images, stock photos, or royalty-free images along with your topic, you will be able to narrow your search to royalty-free items. Some search engines can help you filter your search by license type as well. For example, Google Images includes a search tool that allows you to filter the results by license type. We should mention, however, that this tool is not perfect, and you should check the source of the image directly for its licensing requirements. You should not take an image from a search engine unless you are sure the creator has provided a license that allows you to do so.

When searching Google Images, you can search for images with specific permissions by clicking “Search Tools,” then “Usage Rights.”

You could also use a stock photo website that provides pay-per-use professional photos. Even on these sites, you also need to be sure that the creator has provided a license for the image to be used freely in the way you intend to use it (for example, under a Creative Commons license).

About Copyright

Any time an individual or group creates something, such as a visual, they automatically have the rights to that visual and copies of it (i.e., copyright). They do not need to register with any organization in order to get the copyrights for their work; it is assumed as soon as they create it. This means that others must seek permission, and often pay a fee, to use the work. For example, a photographer might sell one of their photos to a magazine under the condition that they will be paid based on the number of copies printed or sold.

About Creative Commons

Creative Commons allows creators to share their work with fewer restrictions than copyright. There are four distinct conditions available in a Creative Commons license: attribution, share-alike, non-commercial, and no derivatives. Upon creating a work, an author may attach a Creative Commons license that combines these conditions. The table below outlines the conditions in more detail.

|

Attribution – BY | Others may copy, distribute, display, and perform your copyrighted work, and create derivatives based on (adapt, modify) your work, so long as they give you credit the way you request. |

|

Non-Commercial – NC | Others may copy, distribute, display, and perform your copyrighted work, and create derivatives based on (adapt, modify) your work, but for non-commercial purposes only. |

|

ShareAlike – SA | Others may create and distribute derivatives based on (adapt, modify) your work, but they must use an identical license to the license that your work uses. |

|

No-Derivative Works – ND | Others may distribute, display, and perform your copyrighted work; however, their material must be your work verbatim, not derivatives of your work. |

For example, an author may wish to have their work distributed and available for free, but does not want anyone to change their work. They might consider using a Creative Commons attribution, no-derivatives license. Their work would include the following image and statement, as well as a hyperlink to the license deed:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

When using Creative Commons works, ensure you follow the license requirements of the work you are using. This often includes identifying the original creator and a link to the Creative Commons license itself.

An image may also be in the Public Domain, meaning that the creator’s intellectual property rights have expired, been forfeited, or are inapplicable. In this case, the image is free to use globally without restriction.

For guidance on how to find Creative Commons materials, using the Creative Commons search portal, see How to Find Creative Commons Materials Using the Creative Commons Search Portal: A Guide for Instructors and Students.

Using your own photos

You could, of course, use any photographs you take yourself. To avoid rights issues, ask any human subjects included in your photos to sign a waiver giving you permission to use their likenesses. In the case of minors, you need to ask their guardians to sign the permission form.

Similarly, pictures taken by friends or relatives could be available as long as you get signed permission to use the photo, as well as signed permission from any human subjects in the photo. Although it might seem silly to ask your sister, for example, to give you signed permission to use her photo or image, you never know what complications you could encounter later on. So, always protect yourself with permission.

Making your own visuals

A third option is to create your visuals. You do not have to be an artist to choose this option successfully. You can use computer programs to generate professional-looking charts, graphs, tables, flowcharts, and diagrams, or hire a graphic designer to do this for you.

Subject your visuals to the same level of scrutiny as your writing. Keep in mind that if you find one person has a problem with one of your visuals, there will be others who also take exception. On the other hand, remember that you can never please everyone, so you will have to use your judgment.

You can generate some types of visuals using Generative AI tools. If you decide to use these tools, remember that you should consider the ethical implications of using them, you should be aware of their limitations, and you should acknowledge your use of any Generative AI tools.

Uses and Abuses of Visuals

Choose visuals to advance your argument rather than just to decorate your pages. Just as you would not include words that are fluff, you should not include meaningless images. Also, just as you aim to avoid the use of fallacies in your text, you also need to be careful not to use fallacious visuals. For example, if you were arguing for the proposition that big dogs make good pets for families, you might show a picture of a friendly-looking Rottweiler puppy. But if you were against families having big dogs for pets, you might choose an image of a mean-looking adult Rottweiler baring its teeth. Watch out for the use of visuals that sway your opinion in the material you read, and use objective images in your own work.

Thanks to programs such as Adobe Photoshop, you can easily alter a photo, but make sure to do so ethically. For example, say that you are making an argument that a company unfairly hires only young people and discharges employees as they age. You decide to show a photo of some of the employees to make your point. You take a photo of the company’s employees (both old and young) and crop the original photo to show only the young employees. This cropping choice would be misleading and unethical.

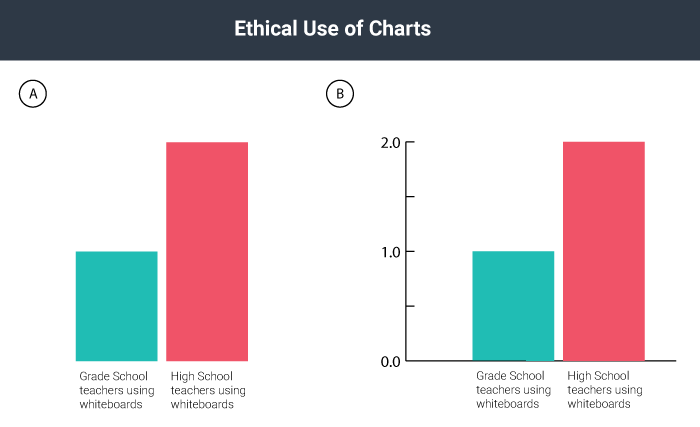

You have probably seen tables or graphs that convey something that is not exactly accurate. For example, the two graphs in the image below could be used as proof that “twice as many” high school teachers as grade school teachers choose to use computer-driven whiteboards. Graph A seems to support this statement nicely. If you look at Graph B, however, you realize that the entire sample includes only two teachers, so “twice as many” means, literally, two rather than one—an inadequate sample that leads to neither impressive nor convincing data. Be very careful not to misrepresent data using tables and graphs, whether knowingly or accidentally.

Weighing Your Options for Visuals

Visuals, like verbal or written text, can make ethical, logical, and emotional appeals. Two examples of ethical appeals are a respected logo and a photo of the author in professional dress. Graphs, charts, and tables are examples of logical appeals. For the most part, nearly all visuals, because they quickly catch a reader’s eye, operate on an emotional level—even those that are designed to make ethical and logical appeals.

Consider the following options when you choose visuals for your work:

- Choose visuals that your audience will understand and appreciate. Besides adding information, visuals help to establish common ground with your audience.

- Consider the possible emotional reactions to your visuals and decide if they are reactions you want to evoke.

- Make sure you choose ethically.

- Make sure you present the information accurately and in a balanced way when using images such as charts and tables.

- Look for royalty-free visuals or create your own, unless you are prepared to pay for visuals.

- Make sure you choose visuals that align with the ethical standards of your work, because visuals can sway readers quickly. If your text is solidly ethical but your picture(s) are inflammatory, you might compromise the ethics of your work.

- Keep captions brief if you need to use them. Some images carry meaning without any explanation. If you cannot keep the caption brief, you probably need a different visual or better context for the visual in the text surrounding it.

Additional Resources

If you would like to read more about finding, using, and attributing Creative Commons–licensed materials, see the following sites:

- How to find Creative Commons–licensed materials

- How to find Creative Commons materials using Google

- How to find Creative Commons materials using YouTube

References

Picardi, R. P. (2001). Skills of workplace communication. [electronic resource] : a handbook for T&D specialists and their organizations. Westport, Conn.: Quorum Books, 2001.

Saunders, A.C. (1994). Graphics and how they communicate. In D.M. Moore and F.M. Dwyer, eds. Visual literacy: a spectrum of visual learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Attributions

"Using Visuals to Communicate" by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted from:

- "6 A Picture Is Worth 1,000 Words: Using Visuals" by JR Dingwall; Chuck Labrie; Trecia McLennon; and Laura Underwood, Professional Communications is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Original content contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College, to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- Content created by Creative Commons, originally published under a CC BY 4.0 international license

- An image of a horse, created by Peter O’Connor, originally published under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license

- An icon created by IconTexto, published under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- An image of a soybean sprout, created by the United Soybean Board, originally published under a CC BY 2.0 license

- A derivative of an icon created by Алексей Миронов, originally published in accordance with IconFinder’s terms of service and the conditions specified by the creator

- A derivative of an icon created by Samat Odedara, originally published in accordance with IconFinder’s terms of service and the conditions specified by the creator

- A derivative of an icon created by the AIGA, originally published under the public domain

- A derivative of an icon created by Google, published in accordance with IconFinder’s terms of service and the conditions specified by the creator

- A derivative of an icon created by Gregor Čresnar, originally published in accordance with IconFinder’s terms of service and the conditions specified by the creator

- A derivative of an icon created by Designmodo, published under a CC BY 3.0 license

- A derivative of an icon created by Alessio Atzeni, originally published in accordance with IconFinder’s terms of service and the conditions specified by the creator

- A derivative of an icon created by Yannick Lung, originally published in accordance with IconFinder’s terms of service and the conditions specified by the creator

- A derivative of an image created by Casito, published under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

- A derivative of an image created by Srm038, published under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- A derivative of an image created by Hwy43, published under a CC BY 3.0 license

- A derivative of an image created by Locke Cole, published under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Creating and Finding Visuals, in Writers’ Handbook, previously shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Incorporating Images, Charts, and Graphs, in Writers’ Handbook, previously shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Incorporating Effective Visuals into a Presentation, in Successful Writing, previously shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- A screenshot of a Google Images search, including

- Puppy on Halong Bay created by Andrea Scaffer, published under a CC BY 2.0 license

- Newborn Basenji puppies, published by copperfeesh, CC BY SA 2.0 license

- Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.