Section 5: Important Moves in Academic Writing

Analyzing the Rhetorical Situation

What is a Rhetorical Situation?

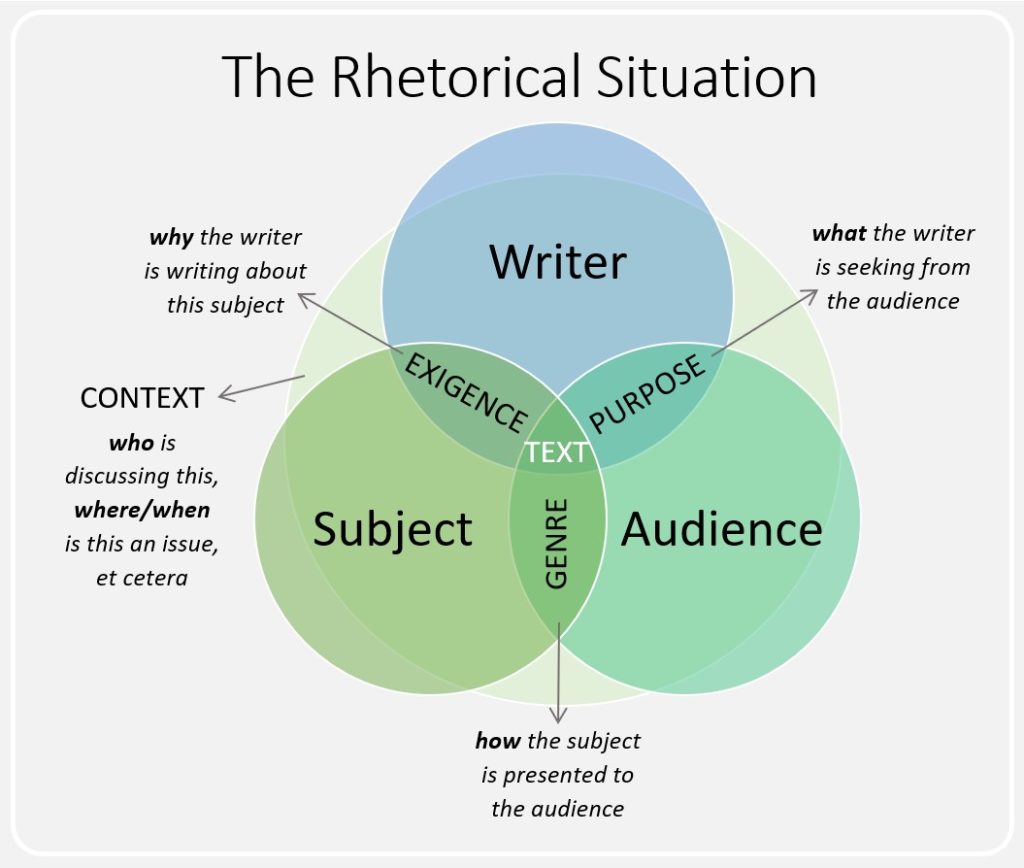

One of the most important skills for a university student to learn is analyzing the rhetorical situation. Analyzing your rhetorical situation means considering your exigence, purpose, audience, timing, genre, and setting when communicating.

Here are brief definitions of these terms to get you started.

- Exigence is the issue, problem, or debate we are responding to

- Purpose is what we hope to achieve in communicating

- Audience is who we are communicating with

- Timing is the best moment to communicate with our audience

- Genre is the type of text or pattern of communication best suited to deliver our content

- Setting includes the constraints related to where the message is being published or delivered (such as a social media platform or within a classroom)

Analyzing the rhetorical situation is something you do already without realizing that’s what you are doing. Take, for example, any time you post to social media. You consider all the friends/followers you have on your account. How will they–individually and collectively–shape what and how you write? People, such as family members, family friends, coworkers, and potential partners, will each shape your message in different ways. This is considering your audience. Other factors that influence your message are genre and the setting in which you deliver it. Genre is the type or kind of text you are writing–it’s a way for writers to classify what type of piece they are writing (a persuasive essay, a newspaper article, a lab report). In our example, a social media post would be your genre. Setting is the space in which the content is delivered, such as which social media platform you will use. Consider the difference between an Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook post. Each requires you to consider length, formality, tone, word choice, and genre and setting-specific conventions such as hashtags and filters. And finally, your purpose and exigence also affect your message. For example, you might post that you need a ride to work (purpose) because your car broke down (exigence).

In the following sections, you will learn more about these elements of the rhetorical situation.

Exigence

Simply put, the exigence of a rhetorical situation is the urgency, problem, or issue that a university assignment asks a student to respond to. Exigence is a rhetorical concept that can help writers and readers understand why texts exist. You can use the concept to analyze what others’ texts are responding to and to more effectively identify the reasons why you might produce your own. Understanding exigence can lead to a better sense of audience and purpose, as well. When you know why a text exists, you will often have a clearer sense of whom it speaks to (audience) and what it seeks to do (purpose).

The rhetorical concept of exigence, also called exigency, is attributed to rhetorical scholar Lloyd Bitzer. In his essay, “The Rhetorical Situation,” Bitzer identifies exigence as an important part of any rhetorical situation. Bitzer writes, exigence is “an imperfection marked by urgency … a thing which is other than it should be.” It is the thing, the situation, the problem, the imperfection, that moves writers to respond through language and rhetoric. Bitzer claims there can be numerous exigencies necessitating response in any given context, but there is always a controlling exigency—one that is stronger than the others.

Some university assignments ask a student to brainstorm, research, and clearly explain their own exigency and then respond to it. Other assignment prompts will give students a pre-defined exigency and ask them to respond to or solve the problem using the skills they’ve been practicing in the course. When analyzing texts or creating their own, students should specify the urgency their discourse is responding to. In thesis-driven academic essays, the exigency is usually clarified at the beginning, as part of the introduction.

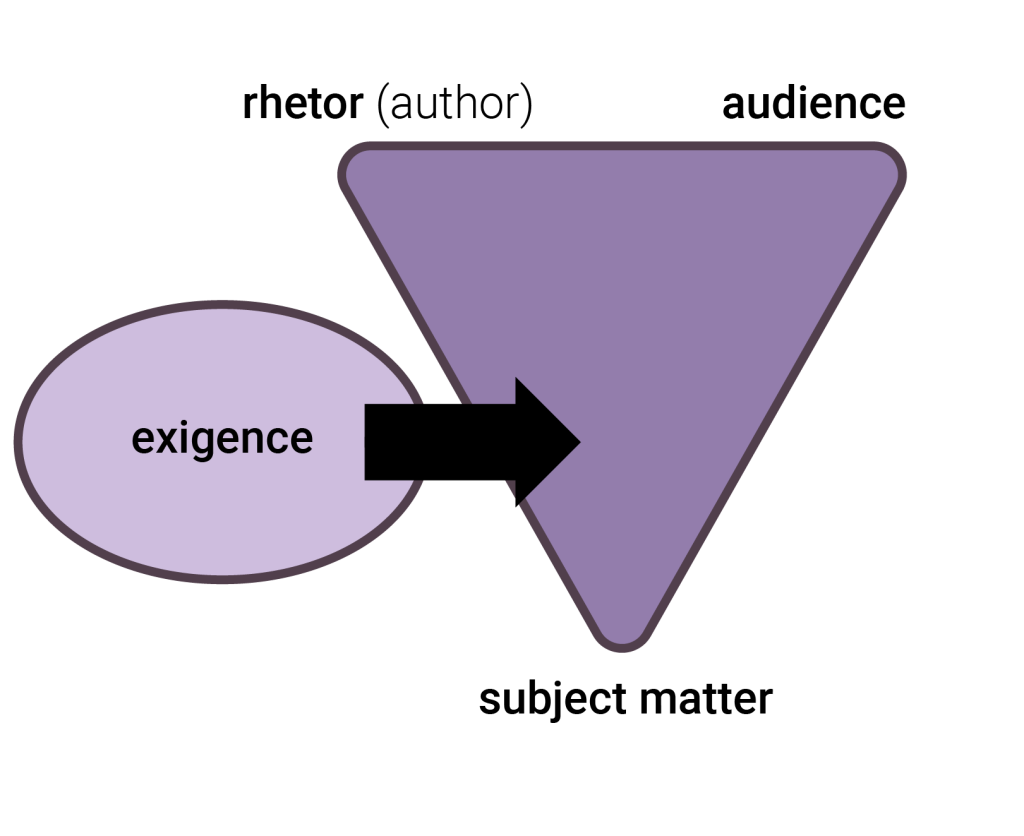

We can visualize the relationship between exigence and those other rhetorical concepts as cause and effect: the exigence gives rise to the rhetorical situation. In other words, all rhetorical situations respond to a particular need or urgency. It motivates the rhetor (writer/author/speaker) to act.

Another way to think about the relationship between exigence and other elements of rhetoric (especially the purpose) is in terms of problem and solution: an exigence is a problem that demands a solution. All rhetorical situations are particular, inventive solutions to a pressing issue.

Questions related to exigence:

- What has moved the writer to create the text?

- Why are these discourses needed right now?

- What is the writer and the text responding to?

- What was the perceived need for the text?

- What urgent problem or issue does this text try to solve or address?

- How does the writer, or text, construct exigence—something that prompts a response—for the audience?

Purpose

One straightforward way to understand the purpose of a rhetorical situation is in terms of the exigence: the purpose of an essay, presentation, or other artifact is to effectively respond to a particular problem, issue, or dilemma.

Here are some rhetorical situations where the exigence and purpose are clearly defined. Notice how the purpose is intimately related to the exigence. The last situation is unique to university courses.

Example 1

I need to write a letter to my landlord explaining why my rent is late, so she won’t be upset.

Purpose of the letter = to persuade the landlord that it’s ok to accept a late payment.

Example 2

I want to write a proposal for my work team to persuade them to change our schedule.

Purpose of the proposal = to persuade the team to get the schedule changed.

Example 3

I must write a research project for my environmental science instructor comparing solar to wind power.

Purpose of the research project = to inform the audience about alternative forms of energy.

However, the assignment also has a hidden purpose: to persuade the science instructor that you’re learning the course content.

The difference between Exigence 1 and Exigence 3 above may initially cause some confusion:

Exigence 1, the letter about the late rent payment, happens in the “real world.” It’s an everyday occurrence that naturally gives rise to a certain rhetorical situation, and the purpose seems obvious.

In Exigence 3, the writing situation feels more complex because the student is learning about things supposedly “out there,” in the “real world,” but the purpose has multiple layers to it because it’s part of a university course. On the surface, the purpose of the research essay is obviously to inform the reader, but since the assignment is given within a science course, the student is also attempting to convince the instructor that they’re learning the course outcomes.

The example of Exigence 3 shows how university assignments sometimes differ from other writing situations. A contextual appreciation of a text’s purpose helps students appreciate why they’re given certain assignments. In a typical writing course, for example, students are often asked to respond to situations with their own persuasive or creative ingenuity, even though they’re not expected to become experts on the topic. Until they enter high-level or graduate-level courses, students are mostly expected to simulate expertise.

When this simulation happens, we can consider an assignment and the student’s response as having two distinct purposes. The first is obvious and usually stated; the second is often implied.

Purpose 1: Obvious purpose. On the surface, the purpose of the assignment might be to solve a problem (anthropogenic climate change, the rise of misinformation, etc.) and persuade an academic audience that their solution is legitimate, perhaps by synthesizing research. Depending on the topic and assignment criteria, a student might pretend to address a specialized audience and thereby simulate a position of authority (a type of ethos), even if they haven’t yet earned the credentials.

Purpose 2: Hidden purpose. When simulating expertise, instructors and students should also consider the context of the writing assignment prompt: it’s given to the student as part of a university writing course. The outcomes for that course shape the assignments an instructor chooses and how they’re assessed. The hidden or implied purpose is therefore the course objectives that the student is expected to demonstrate, including techniques such as developing a thesis, providing support, synthesizing research, and writing with sources.

University writing assignments can thus have multiple purposes. The more attuned a student is to why they’re being tasked with certain assignments, the more their writing will matter, both for them and others.

How are purpose and audience related? Often, you’ll know your purpose at the exact moment you know your audience because they’re generally a package deal.

Example 1

I need to write a letter to my landlord explaining why my rent is late, so she won’t be upset.

Audience = landlord

Purpose = keeping her happy

Example 2

I want to write a proposal for my work team to persuade them to change our schedule.

Purpose = persuading them to get the schedule changed

Example 3

I have to write a research project for my environmental science instructor comparing solar to wind power.

Purpose = analyzing/showing that you understand these two power sources

Sometimes your instructor will give you a purpose, like in the third example above, but other times, especially out in the world, your purpose will depend on what effect you want your writing to have on your audience. What is the goal of your writing? What do you hope for your audience to think, feel, or do after reading it? Here are a few possibilities:

- Persuade them to act or think about an issue from your point of view.

- Challenge them/make them question their thinking or behaviour.

- Argue for or against something they believe or do/change their minds or behaviour.

- Inform/teach them about a topic they don’t know much about.

- Connect with them emotionally/help them feel understood.

Audience

Audience is a rhetorical concept that refers to the individuals and groups writers attempt to move, inciting them to action or inspiring shifts in attitudes and beliefs. Thinking about the audience can help us understand who texts are intended for, or who they are ideally suited for, and how writers use writing to respond to and move those people. While it may not be possible to ever fully “know” one’s audience, writers who are good rhetorical thinkers know how to access and use information about their audiences to make educated guesses about their needs, values, and expectations—hopefully engaging in rhetorically fitting writing practices and crafting and delivering useful texts. In short, to think about the audience is to consider how people influence, encounter, and use any given text.

In their essay “Audience Addressed/Audience Invoked,” Andrea Lunsford and Lisa Ede discuss the difference between an addressed (or actual) and an invoked (imaginary) audience. Addressed audiences are the “actual or intended readers of a text,” and they “exist outside the text” (167). These audiences are actual people who have values, needs, and expectations that the writer must anticipate and respond to in the text. People can identify actual audiences by thinking about where and when a text is delivered, how and where it circulates, and who would or could encounter the text.

On the other hand, invoked audiences are created, perhaps shaped, by a writer. The writer uses language to signal to audiences the kinds of positions and values they are expected to identify with and relate to when reading the text. In this sense, invoked audiences are imagined by the writer and, to some degree, are ideal readers that may or may not share the same positions or values as the actual audience.

Some related questions to keep in mind when considering your audience:

- Who is the actual audience for this text, and how do you know?

- Who is the invoked audience for the text and where do you see evidence for this in the text?

- What knowledge, beliefs, and positions does the audience bring to the subject-at-hand?

- What does the audience know or not know about the subject?

- What does the audience need or expect from the writer and text?

- When, where, and how will the audience encounter the text, and how has the text—and its content—responded to this?

- What roles or personas (e.g., insider/outsider or expert/novice) does the writer create for the audience? Where are these personas presented in the text, and why?

- How should/has the audience influenced the development of the text?

Timing

In every rhetorical situation, we should determine the best moment to communicate with an audience; the Ancient Greeks called this aspect of the rhetorical situation kairos. For example, say you want to convince your parents to buy you a new computer. You are more likely to successfully persuade them if you choose a moment when they are not distracted by other worries. This same principle applies in all communication situations.

Genre

Let’s begin by imagining the world—the worlds, rather—in which you write. Your workplace, for instance: you might take messages, write e-mails, update records, input orders, or fill out various forms.

Or what about your educational world? You likely write in response to all kinds of assignments: lab reports, researched arguments, short summaries, observations, even, sometimes, short narratives. Sometimes you might write a short message on Canvas or via e-mail to your instructors. You may also have financial aid forms to fill out or application materials for the scholarship to complete.

What about your world outside of school or work? Do you, occasionally, write an Insta caption, post on X (formerly Twitter), or create a Snapchat story? Do you repost other people’s articles and memes with your own comments? How about texts to friends and acquaintances? You might also be a writer of what we sometimes label as creative texts—you might write songs or song lyrics, poems, or stories.

The names of the things you write—e-mails, application forms, order forms, lab reports, applications, narratives, text messages, and so on—can be thought of as individual compositions, large or small, that happen while doing other activities. But another way to think of these compositions is as predictable and recurring kinds of communication—in a word, genres.

The term genre means “kind, sort, or style” and is often applied to kinds of art and media, for instance, sorts of novels, films, television shows, etc. In writing studies, we study all kinds of written genres, not just ones you might classify as artistic (or creative).

Genre is a word we use to classify things, to note the similarities and differences between kinds of writing. We begin to classify a kind of writing as a genre when it recurs frequently enough and performs the same functions in recurring situations. All the documents listed earlier in this chapter are examples of genre, and all of them are subject to constraints.

A genre constraint is simply the rules we use to create a genre. One example might be the kind of speech students are asked to deliver to their communication class. The professor may have asked students to develop expository and persuasive speeches. When preparing for these assignments, students are often given a set of expectations, including a basic structure, style, and whether certain persuasive appeals are relevant. A student can then research a topic of their choice and craft a speech following these rules.

This process is not dissimilar from how a maid of honour will search on the web for “how to do a maid of honour speech” before a wedding. There is a well-known set of conventions that people draw from, and, at the same time, cultures and subcultures will introduce slight innovations within those recurring forms. The ability to identify a “persuasive university speech” or a “best man’s speech” is both an act of naming and a form of classification.

That’s genre awareness: an ability to map an assignment or another rhetorical situation to a relatively stable form that recurs across time and space.

Why should students think about genre?

The idea of genre in university writing situations is useful because it will help you think more deliberately about how the finished assignment (sometimes known as an artifact) should appear. One of the most common anxieties or frustrations students have in a writing course is what their essay should ultimately look like. Some instructors provide highly detailed models, including templates for every part of the essay. Others simply state something like: “write a persuasive essay about x,” and students are expected to figure out the details of what a persuasive essay looks like on their own. When you ask your professor how to ‘format’ the essay, you are asking for information about the genre conventions.

How can students become less anxious about what their essay should look like?

There are a lot of ways that students can become less anxious about the genres in which they write:

- Ask the instructor if they have any examples of previous student work they would share.

- Ask your classmates how they are going to format the document.

- Remember: do not use their WORK as your own, just follow their formatting.

- Do an internet search to see if there are any examples you can use.

You’ll quickly find out “in the real world” that genre is highly relevant to success! Workplace environments have many different genre expectations, and it’s often the case that employees are asked to write things they’re unfamiliar with. The more practice you have with identifying a task’s genre and the conventions associated with it, the more successful you’ll be at your job. Even getting a job requires familiarity with the genre—the resume!

Setting

When analyzing the setting of the rhetorical situation, we consider the physical and digital context in which the communication will take place. For example, if you are delivering a presentation, it will matter if this presentation is online or in person. You will include different strategies to engage the audience in the different settings.

When we write, particularly when we write on digital platforms, we should consider the setting in which the audience is going to receive our message. If your audience is likely to read your message on their phone, consider how to make that message as clear and concise as possible.

References

Bitzer, L. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 1(1), 1–14.

Ede, L., & Lunsford, A. (1984). Audience addressed/audience invoked: The role of audience in composition theory and pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, 35(2), 155–171.

Attributions

“Analyzing Rhetorical Situations” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted from:

- “21. Exigence” by Joel Gladd, Write What Matters is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- “6.2. Purpose” by Monique Babin, Carol Burnell, Susan Pesznecker, Nicole Rosevear, Jaime Wood, Introduction to Writing in College is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- “Audience” by Justin Jory, Open English @ SLCC, Salt Lake Community College is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0