Section 2: The Writing Process

Providing and Receiving Feedback

When we write, we may actually forget our readers. We write from inside our heads and know exactly what we mean. However, when others read our writing, they may find gaps in content. They may be unable to follow the ideas’ logic or order. They are not inside our heads, so they may be missing the critical information that lends meaning to the text. Revising your writing with the reader in mind can be easier when you get help from others. Feedback to the rescue!

Most writers seek feedback after they have developed a solid draft they are willing to share with readers. Expert writers will use the feedback they receive to make substantial changes to their draft–this process is called revising. You can read more about how to revise in the chapter “Revising.”

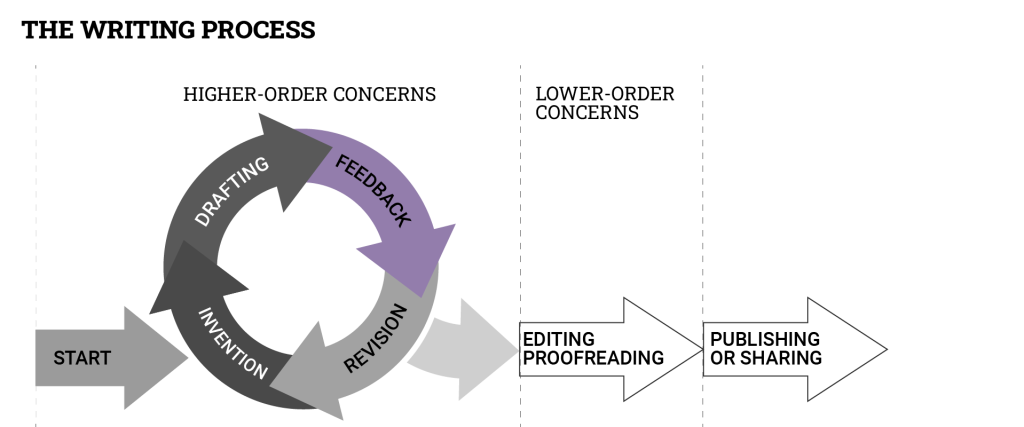

Figure 1 shows feedback as part of an iterative writing process.

Writing is complex work, and the best writers rely on others for constructive feedback. Seeking feedback on your writing through peer review, course instructor comments, and writing centre appointments draws you into a community of writing practice. Think of writing as a craft, something that is learned over time, an activity that has no ceiling on its performance.

When you seek feedback, consider what type of feedback you need and who might best provide you with that feedback. You must also consider your reactions to feedback: How can you best hear and understand potential criticism of your text without getting defensive?

When you are asked to provide feedback, you need to consider what type of feedback is most appropriate and how to convey your feedback in a respectful and effective manner.

The following sections explore these aspects of feedback in more detail.

What Kind of Feedback Should You Ask for?

The kind of feedback you seek should be related to where you are at in the writing process. You should ask for different types of feedback if you are at the drafting stage or if you are at the proofreading stage. In other words, if you are working on higher-order concerns like content and organization, you should ask for feedback on those elements. If you are working on lower-order concerns like style and grammar, you should ask for feedback on those elements. This distinction is important because feedback providers may default to providing feedback on lower-order concerns; it is more straightforward feedback to provide, and many people are not practiced at providing feedback on higher-order issues.

Do you have an assignment that requires writing? Take it out now and see if you can find the rubric or how your writing will be marked. The assignment instructions and grading standards or rubric clarify your course instructor’s expectations. These expectations may be grouped into possible categories such as organization, content, sentences/grammar, and format. Each category may include specific criteria (e.g., “strong thesis statement” or “argument clarity”) with accompanying marks for fulfilling this criterion. You can use this information to ask for feedback specifically related to your instructor’s expectations.

You may have a particular weakness when it comes to writing. For instance, your thesis statements may not be as concise as they should be. You should direct your feedback provider to check this element of your writing.

Who Should You Get Feedback From?

Expert writers

For high-stakes writing projects, you might want to seek feedback on your draft from expert writers. As students, you may be able to ask your instructors for feedback. However, be aware that these are busy people, and they may have limited time to divide equally among their students. If you do have an instructor who provides you with feedback on your draft, you have been given a special gift.

Of course, you will get feedback from your instructors on the final draft of your writing in the form of a grade.

Advanced writers

If your course has teaching assistants, you may be able to get feedback on your drafts from them. Teaching assistants are typically graduate students who have done well in undergraduate programs and have mastered academic writing at a high level. Your teaching assistants’ ability to provide feedback may be linked to whether feedback to students was included in their contracts.

Most post-secondary institutions have writing centres where students can receive feedback on their drafts from staff or tutors trained to provide feedback on many different types of writing. Even if you are a strong writer, talking about your writing with these advanced writers can help you untangle the knots in a text.

Peers

Your peers are an excellent resource for feedback. Your instructor may group you with peers so that you can provide feedback on each other’s drafts as part of your coursework. Peer feedback in a course is an excellent way to hear from readers who are learning the same material and may have good insight into what your instructor expects.

If your course does not include peer feedback, you could organize it yourself. Ask a fellow student or students if they would be interested in providing feedback on drafts. If you are in a writing-intensive course, you could establish a writing group, which is a group that meets to discuss and provide feedback on writing regularly.

Family and friends

Your family and friends can be excellent test readers. They are usually the friendliest audience, which has advantages and disadvantages. These readers will love us no matter the issues with our writing; however, they might not see important areas for improvement.

Remember to give your family and friends explicit instructions about the type of feedback you seek about your writing.

How Can You Receive Feedback Effectively?

Sometimes, receiving feedback is hard. You may feel hurt by what you hear. Remembering that feedback is a gift helps reduce that sting. Respond to feedback by thanking the person who gave it to you and carefully listening to (or reading) the advice. You may wish to ask questions for clarification so you are sure you understand what you might do to improve. Avoid becoming defensive or rationalizing your choices, as this may frustrate the person providing feedback. Why ask for feedback if you are not going to listen carefully to it?

You may also wish to ignore the feedback if it does not make sense or departs from your course instructor’s expectations. As the writer, you are in the driver’s seat and can choose whether or not to implement the suggestions you receive. As a general principle, if you hear the same feedback from more than one reader, there is a good chance that you should listen to it.

How Should You Offer Feedback?

American writer and cartoonist Frank A. Clark says, “Criticism, like rain, should be gentle enough to nourish a man’s growth without destroying his roots” (qtd in BrainyQuote, 2025). In offering feedback, your goal is to help your peer improve. To help your peer, you need to deliver your feedback in a way that your peer will hear.

First, you want to emphasize what works well in your peer’s writing using scripts like these: “I really like the interesting anecdote you include in your introduction” or “Your sentences are easy to understand.”

Second, you can highlight opportunities for growth. You may want to try asking questions:

- “Are you sure that ‘contemptation’ is a word?” or “What do you mean when you say, ‘the be all is sublime’?”

- You can offer suggestions from your writing experience: “When I find one of my paragraphs is going on for several pages, I consider breaking it down into shorter paragraphs.”

- You can speak to your experience reading the text: “I am getting sleepy as I read your middle section. I’m having trouble following your main point.”

Finally, you can point your peer to resources you’ve found helpful: “When I need help with writing paragraphs, I look at the OWL’s page “On Paragraphs.” Hearing about the resources you’re using might inspire your peers to check them out.

Reading others’ writing opens our eyes to our own strengths and challenges as writers. When we read our peer’s writing and find gaps between ideas, we are reminded of our own need to ensure that connections are clear. Struggling to locate key points in long, repetitious sentences shows us the need to write clear sentences in plain language. Scrutinizing facts our peers share and wondering about sources highlights the importance of citing sources. Reading the writing of others is a window to improving our processes and products.

Using Generative AI for Feedback

Consider academic integrity

Please check with your instructor, course syllabus and your institution’s policies about using Generative AI before you use these tools to provide you with feedback on your text.

Use it effectively

If you want to use Generative AI to provide feedback, develop effective prompts. For instance, it will not likely be helpful to ask Generative AI, “Tell me what to fix in my draft.” Effective prompts will be specific and directive. For example, you might prompt Generative as follows:

- I am a first-year student at university. I’m writing a rhetorical analysis of an opinion article. The instructor has given us the following instructions for this assignment: [Insert instructions]. Given these instructions, please provide me with the strengths and areas for improvement for the following text. Focus on higher-order concerns like content and argumentation. Do not rewrite my text. [It is important to remind the LLM not to rewrite your text for you. You want its feedback, but not its writing.]

Beware of the limitations

- Generative AI will teach you to write in a homogenized way. It looks for common patterns in texts, and it will advise you on ways to ensure that your text follows those patterns. Ultimately, this could lead to uninspired and dull writing. This might not be what you want.

- Generative AI might not recognize aspects of your writing that are specific to your context. For example, your instructor may have given you specific instructions on formatting a thesis statement, but Generative AI may not know this or how to help you with this. Writing always takes place in a very specific situation where there are specific relationships between the reader and the writer. Generative AI cannot reflect these specific situations and relationships in writing, and this is often evident to the reader.

Consider your learning journey

Learning to review your writing and recognize shortcomings is an essential part of becoming a better writer. If you rely too heavily on Generative AI to provide feedback on your writing, you might miss out on this learning opportunity. As a general principle, you should use Generative AI in ways that improve your own abilities to write and think.

Consider ethics

Consider the ethical implications of using these tools. Make sure you acknowledge your use of Generative AI in the acknowledgements section of your work.

Additional Resources

At the University of Alberta, you can get feedback from peer tutors at Writing Services.

The MIT Comparative Media Studies/Writing unit has produced an excellent video on peer feedback in the classroom called “No One Writes Alone: Peer Review in the Classroom – A Guide for Students.” (6:33)

References

BrainyQuote. (2025.). Frank A. Clark Quotes. https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/frank_a_clark_105689

Attributions

“Providing and Receiving Feedback” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 and was adapted from:

“1.7 Feedback: No One Writes Alone” by Nancy Ami, Natalie Boldt, Sara Humphreys, and Erin Kelly, Why Write: A Guide for Students, British Columbia/Yukon Pressbooks is licensed under CC BY 4.0