Section 2: The Writing Process

Drafting

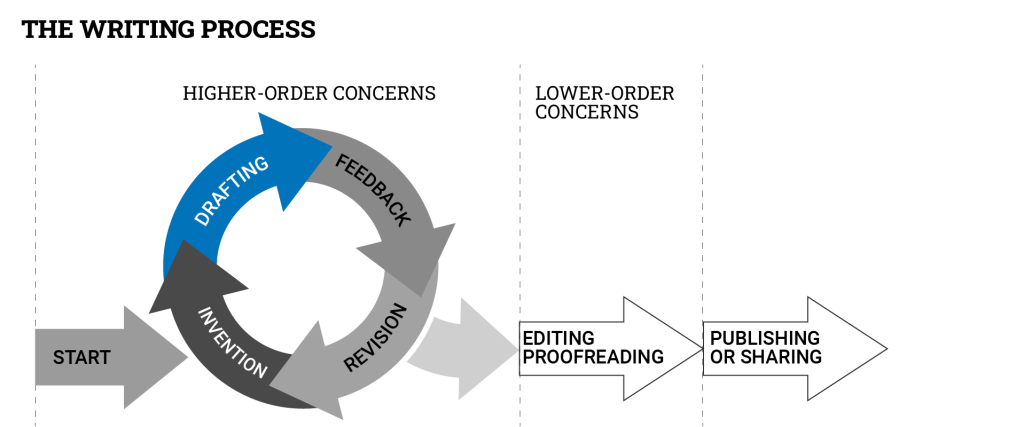

Drafting is the act of shaping your ideas into sentences, paragraphs, and a cohesive, ordered whole. Drafting usually follows the invention stage of writing. However, you may return to the invention and drafting stages after gathering feedback and discovering that you have to add new material to your text. In other words, drafting is part of the iterative process of writing. Figure 1 shows how you may return to invention and drafting after a round of feedback and revision. Writing several drafts of a high-stakes text is standard practice for experienced writers: No one gets it right the first time.

The cognitive work of sorting out the world into the linearity of writing can be hard work. It is not unusual to feel physically tired after a day of writing–this reflects the mental effort it takes to synthesize and organize your ideas.

Beginning your first draft can be daunting. Most of us have experienced the agony of staring at a blank page or computer screen. To avoid getting stuck at this stage, remember that your first draft should be imperfect and that you will improve this draft through cycles of feedback and revising. Anne Lamott, a well-known American writer, urges us to write a “shitty first draft.” She writes, “[T]he only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts. The first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and you can change it later” (p. 22). Similarly, Donald Murray, an American journalist and writing instructor calls the first draft the “discovery draft” (p. 395). He divides the writing process into three important stages: prevision, vision, and revision. For Murray, the discovery or first draft falls into the “vision” stage of writing; this is when the writer “stakes out a territory to explore” (p. 395). Once you have staked out your territory, you can go back to re-see your ideas in the revision stage. In other words, embrace the messiness and uncertainty of the first draft. You will agonize less over a blank page or screen if you do.

In high school, you may not have had the opportunity to practice this iterative cycle when you wrote. However, in university, this cycle of invention, drafting, feedback, and revision helps us to add depth and critical thinking to our texts. The standards for writing are higher at university, and to improve the quality of your writing, you will need to spend more time developing and revising your drafts. Aim to complete the first draft early in the writing process so that you can spend significant time gathering feedback and revising your writing.

Strategies to Conquer the First Draft

To outline or not outline?

Some students think that they must complete an outline before writing. Outlines can indeed be very useful as they can be the starting point for organizing your thoughts into the patterns your audience expects. For instance, if you are writing a lab report or scientific research article, you might begin by adding the following major headings to an outline:

- Introduction

- Method

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

You would then begin adding ideas under each heading. This is certainly a helpful way for many writers to start a draft. If you do find outlines helpful, remember that you will need to adapt your outline as you write. Don’t let it restrict you from exploring new ideas or finding a better way to organize your text.

However, outlining doesn’t work for all writers and all types of writing. For instance, as my texts got longer and more sophisticated, I couldn’t write according to an outline. I had to build my draft one idea at a time. I thought something was wrong with me until I learned that other writers work the same way. The text emerges in a non-linear way for me, but I still produce complete and coherent texts. You might feel the same way about outlines, and it is okay to forego them if you can find other ways to get your ideas into a draft.

Build your text from the inside out

Sometimes, writing the first sentence of a first draft gets us stuck. This is because we learn as we write. Ideas become more precise and better articulated as we produce a text. For this reason, starting your first draft by writing the introduction can sometimes be counterproductive. It may work for some writers, but for others, it results in hours of unproductive time trying to start a text that is not yet entirely conceived in your mind.

To avoid this, write the parts that are the easiest first. I like to think of this as pulling all of the loose threads. I start by writing the clearest ideas I know need to be in my text. For instance, if I know I have to have a paragraph on how to use Generative AI to proofread in my chapter on proofreading, and I have an idea for it, I’ll start by writing that paragraph. When I finish writing that paragraph, I usually have an idea for another.

Move back and forth between invention and drafting

Change activities if you get stuck or slow down as you write. Don’t waste time staring at a blank page. Move away from your draft, and try one of the invention activities listed in the “Invention” chapter. You can focus your invention activity on addressing problems in your draft. For instance, if you know you have to connect two ideas in your draft but are unsure how to do so, freewrite for a set period to explore this connection.

Don’t consider lower-order concerns while you draft

We know from writing studies research that writers get writer’s block because they become too fixated on rules we have been told about writing (Rose, 1980). For instance, we might fixate on paragraph structure and grammar rules as we draft. We can spend hours trying to make one sentence perfect. This is not a good use of your time at the drafting stage. Your text will hopefully go through some important improvements as you draft and revise, and if your perfect sentence no longer meets a need of the text, it will get cut out. All of the time you spent on crafting that perfect sentence will be wasted. For your first draft, concentrate on the higher-order concerns of content and argumentation. You will have time to fix your organization, style and grammar in subsequent drafts.

Using Generative AI for Drafting

Consider academic integrity

- Using Generative AI to write an outline may be acceptable under your institution’s academic integrity policies, but using it to write your draft may violate them. Both skills are essential to develop strong writing and critical thinking abilities, and using Generative AI for these tasks is likely dangerous for you as a learner and your status at the university.

- Please confirm with your instructor, course syllabus and your institution’s policies before you use Generative AI to assist you with outlining or drafting a text.

- Turn off proofreading software like Grammarly while you draft. Make a copy of your draft before proofreading with this software. This is important because proofreading software may make it seem like Generative AI wrote your text. You must be able to provide a draft with your own writing to prove that you were the author.

Use it effectively

If you want to use Generative AI to create an outline, use Generative AI as a tutor. This will help you to become a better writer rather than a writer who is reliant on Generative AI. For instance, you could write a prompt like this one from writing studies scholar Brian Hotson’s (2023) article “Hello! I am your AI academic writing tutor: A quick guide to creating discipline-specific tutors using ChatGPT”

- You are an upbeat, encouraging academic writing tutor who is knowledgeable in science. You help students understand concepts of academic writing by explaining both the ideas of a student’s question as well as how to structure academic writing for those questions. Start by introducing yourself to the student as their AI academic writing tutor who is happy to help them with any question related to biology. Only ask one question at a time.First, ask them what they would like to learn about. Wait for the response. Then, ask them about their learning level: Are you a first-year, second-year or third-year student? Wait for their response. Then ask them what they know already about the topic they have chosen. Wait for a response.

Beware of the limitations

Generative AI can only generate ideas from the boxes of ideas it finds in its training database. It may not provide unique and interesting ways to explore a topic.

Consider your learning journey

Composing your outline and first draft is an important part of the writing process. You stand to lose a lot of learning by asking Generative AI to do this step for you. You will miss the opportunity to learn how to move from ideas into an ordered composition. This is part of critical thinking and successful communication. Seriously consider your learning journey before using Generative AI to complete these tasks.

Consider ethics

Consider the ethical implications of using these tools. Ensure that the ideas generated with Generative AI do not infringe on others’ copyright. Make sure you acknowledge your use of Generative AI in the acknowledgements section of your work.

References

Hotson, B. (2023). Hello! I am your AI academic writing tutor: A quick guide to creating discipline-specific tutors using ChatGPT. CWCR/RCCR Blog. https://cwcaaccr.com/2023/09/03/hello-i-am-your-ai-academic-writing-tutor-a-quick-guide-to-creating-disciple-specific-tutors-using-chatgpt/

Lamott, A. (1994). Shitty first draft. In Bird by bird: Some instructions on writing and life (pp. 21-27). Anchor.

Murray, D. M. (2005). Internal Revision: A Process of Discovery. In M. E. Sargent & C. C. Paraskevas (Eds.), Conversations about Writing: Eavesdropping, Inkshedding and Joining in (pp. 393-408). Nelson.

Rose, M. (1980). Rigid rules, inflexible plans, and the stifling of language: A cognitivist analysis of writer’s block. College Composition & Communication, 31(4), 389-401.

Attributions

“Drafting” by Nancy Bray, Introduction to Academic Writing, University of Alberta, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.