5 Critical Theory to Cultural Studies (by Cassandra Riabko & Amanda Williams)

Introduction

Critical and cultural studies converge where power, ideology, and culture influence how meaning is formed and interpreted. Critical studies focus on the power structures and inequalities within cultural practices, examining how these systems sustain dominance and shape social hierarchies. Cultural studies explore how these practices, including media and everyday activities, interact with societal norms, values, and identities.

This intersection allows for a deeper understanding of how media and cultural products both reflect and reinforce societal norms. By combining these perspectives, we gain tools to challenge dominant narratives and analyze the complexities of cultural production and interpretation, particularly in relation to media, identity, and power.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to

- Identify why critical theory and cultural studies are an important part of communication studies.

- Recognize the historical context in which critical theory and cultural studies are embedded and their relationship to each other as important schools of thought.

- Describe some of the foundational principles of both these schools of thought, with a focus on Stuart Hall’s encoding and decoding model.

- Understand the value of critical theory and cultural studies when applied to contemporary examples.

- Discuss potential limitations to both these approaches (critical theory and cultural studies).

History of Critical Theory and Cultural Studies and Key Thinkers

Critical theory and cultural studies share a rich and complex history, marked by a deep exploration of power, culture, and society.

The Frankfurt School, officially known as the Institute for Social Research, emerged as a prominent intellectual force in the early to mid-20th century (Corradetti, n.d.). Established in Frankfurt, Germany, the school attracted scholars such as Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, and Jürgen Habermas, who collectively developed critical theory—a framework for analyzing and critiquing society and culture (Corradetti, n.d.).

The Frankfurt School focused on comprehending and criticizing the emergence of mass culture. Mass culture can be understood as the cultural products and experiences that are mass-produced and extensively distributed, often through media channels, shaping the collective consciousness of society (Celikates & Flynn, 2023). The school’s theorists explored how capitalist systems perpetuate inequality and commodification through the mass media and cultural industries. Capitalism, an economic system characterized by private ownership of the means of production and the pursuit of profit, was a key part of their critique (Corradetti, n.d.).

The Frankfurt School’s critical theory focused on unravelling the complex relationships between culture, ideology, and power. Ideology refers to a system of beliefs and values that shape societal norms and practices, often reflecting the interests of dominant social groups (Corradetti, n.d.). Scholars like Adorno and Horkheimer famously examined the role of culture in the “culture industry,” arguing that mass-produced cultural products served to pacify and manipulate the masses, reinforcing existing power structures (Celikates & Flynn, 2023). Habermas, a key member of the Frankfurt School, further developed critical theory by introducing the concept of the public sphere. Habermas argued that in modern societies, the public sphere serves as a space for rational debate and discussion, where citizens can engage in informed discourse on matters of common concern. He emphasized the importance of an inclusive and deliberative public sphere for fostering democratic participation and holding power structures accountable (Media Texthack Team, 2014).

While the Frankfurt School primarily focused on class dynamics and the critique of capitalism, its influence extended beyond economics to encompass broader social and cultural phenomena. However, by the mid-20th century, the rise of fascism in Europe forced many members of the Frankfurt School into exile, with several relocating to the United States (Corradetti, n.d.).

In 1964, the University of Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies was founded by Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall, establishing the so-called “Birmingham School” of cultural studies (Andrews, 2020). This marked a significant departure from the Frankfurt School’s primary focus on class dynamics, as the Birmingham School expanded its critical inquiry to include questions beyond class (Lave et al., 1992). Despite this shift in focus, both schools shared key perspectives, particularly a critical approach to culture.

Hall, a pioneering figure in cultural studies, significantly shaped our understanding of culture, identity, and power dynamics in contemporary societies, drawing upon the insights of the Frankfurt School. His theoretical framework, deeply rooted in Marxism, offers invaluable insights into how culture operates as a site of struggle, negotiation, and meaning-making (Hsu, 2017). At its core, Hall’s cultural studies theory challenges traditional approaches to understanding culture, which often prioritize fixed meanings and homogenous identities. Instead, he advocates for an approach that acknowledges the fluidity and contingency of culture, emphasizing the role of language, representation, and discourse in shaping social reality (Hsu, 2017). Central to his theory is the concept of encoding and decoding, which highlights the active participation of individuals in interpreting and making sense of cultural texts (Hall, 1980). This concept bridges the insights of the Frankfurt School with the evolving field of cultural studies, providing a framework for understanding how culture shapes and is shaped by societal dynamics.

Foundational Concepts

There are several foundational concepts key to critical theory and cultural studies, (Griffin, 2023). Each is outlined below.

The “culture industry”

The culture industry, a concept introduced by Frankfurt School theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in 1944, describes the mass production and distribution of cultural products like films, music, literature, and art in capitalist societies. These products are often designed to appeal to the widest possible audience, resulting in standardized and formulaic content (Adorno & Horkheimer, 2019).

Understanding the culture industry is essential to critical theory because it sheds light on how capitalist systems shape and control cultural production, ultimately influencing society’s values, beliefs, and behaviours. Adorno & Horkheimer (2019) argue that the culture industry perpetuates consumerism, reinforces dominant ideologies, and serves the interests of those in power by promoting conformity and passivity among the masses.

An Example in Practice

The music industry, particularly the phenomenon of pop music, provides a great example of the culture industry in action. Consider the case of a chart-topping pop song like Despacito by Luis Fonsi (2017) which became a global sensation.

Despacito exemplifies the mass production and dissemination of cultural products within capitalist societies. The song features catchy melodies, repetitive hooks, and simple lyrics, making it easily digestible for a wide audience. Its infectious beat and danceable rhythm contributed to its rapid rise to the top of music charts worldwide.

Major record labels heavily invest in promoting such pop hits through radio airplay, music videos, and online streaming platforms. They leverage marketing tactics to create hype and ensure maximum exposure, capitalizing on the song’s popularity to drive album sales and concert attendance.

Viewed through a critical theory lens, Despacito epitomizes the cultural industry’s inclination to prioritize commercial success over artistic integrity. Despite its undeniable popularity, the song may lack substantive lyrical content or meaningful social commentary, conforming to formulaic standards established by the music industry. Upon repeated listens it may even start to sound indistinguishable from other mainstream hits.

Ideology

While this was touched upon as a key term in chapter 4 on semiotics linked to myth, in critical theory, particularly as developed by the Frankfurt School, ideology refers to a system of beliefs, values, and norms that serve to justify and perpetuate existing power structures and social relations within a society. Ideology plays a central role in shaping individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours, often concealing underlying inequalities and legitimizing the status quo (Corradetti, n.d.).

When discussing ideology within the framework of critical theory focused on class, scholars like Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse were particularly interested in understanding how dominant ideologies, such as capitalism, shape people’s understanding of social reality and their positions within it (Corradetti, n.d.).

An Example in Practice

A contemporary example that illustrates the influence of capitalist ideology on class dynamics and cultural production is the phenomenon of reality television shows like Keeping Up with the Kardashians.

These reality shows often present a glamorized and aspirational lifestyle centred around wealthy individuals or families, such as the Kardashian-Jenner family. Through carefully curated narratives and extravagant displays of wealth, these programs promote consumerism, individualism, and the pursuit of material success as markers of social status and happiness.

By showcasing opulent lifestyles and luxury goods, reality TV reinforces the ideology of capitalism, suggesting that success and fulfillment are attainable through the acquisition of wealth and material possessions. This narrative perpetuates the myth of upward mobility and the idea that anyone can achieve prosperity through hard work and determination while downplaying structural barriers and inequalities inherent in the capitalist system.

Moreover, reality TV often serves as a form of escapism for viewers, distracting them from broader social and economic issues and reinforcing the status quo. Instead of challenging existing power structures or advocating for social change, these shows promote individualistic values and consumerist behaviours, maintaining the dominance of capitalist ideology in society.

In this way, reality television exemplifies how capitalist ideology operates within contemporary culture, shaping perceptions of class, success, and social mobility while reinforcing existing power dynamics and inequalities.

The Public Sphere

The concept of the public sphere holds significant importance within critical theory as it serves as a foundational framework for understanding democratic discourse and social critique. Coined by German philosopher Jürgen Habermas in 1962, the public sphere refers to a space where individuals come together as equals to engage in rational deliberation and debate about matters of common concern, free from coercion or domination (Habermas, 1991). In critical theory, the public sphere is seen as essential for fostering informed citizenship, promoting transparency and accountability in governance, and challenging dominant power structures. By providing a platform for diverse voices and perspectives to be heard and debated, the public sphere enables the critique of existing social norms, ideologies, and inequalities, thereby serving as a catalyst for social change and the realization of a more just and democratic society.

An Example in Practice

A contemporary example of the public sphere (Habermas,1991) in action is the social media tool X (formerly known as Twitter), where users engaged in discussions, debates, and activism on various social and political issues. This platform served as a virtual public sphere, allowing individuals from diverse backgrounds to connect, share information, and express their opinions on topics ranging from environmental sustainability to racial justice. Through hashtags, retweets, and trending topics, X facilitated the dissemination of news and ideas, amplifying marginalized voices and challenging mainstream narratives. However, the effectiveness of this platform as a public sphere was also subject to criticism, as issues such as echo chambers, algorithmic bias, and the spread of misinformation could hinder meaningful dialogue and democratic deliberation. Nonetheless, this example illustrates how digital platforms can serve as contemporary spaces for public discourse and civic engagement, reflecting the ongoing relevance of the public sphere concept in critical theory.

The encoding-decoding model

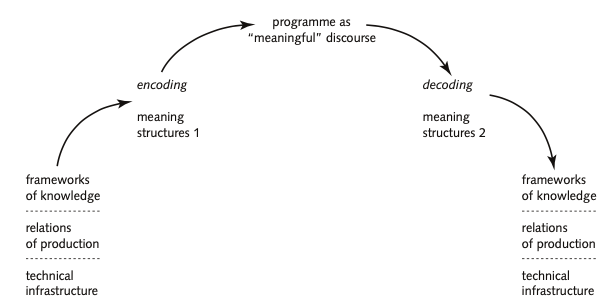

Figure 5.1

Basic Model of Communication

Figure is from Encoding/Decoding (p. 54). In C. Greer (Eds.), Crime and Media: A Reader (1st ed., pp 51–61.). Routledge.

In his work, Hall (1980) extensively examines how meaning is conveyed in mass media, which he labels as the “programme of meaningful discourse.”

Encoding, where producers organize messages to create this discourse, is pivotal. However, Hall notes that the encoded message is shaped by the meaning structures that influence the sender, labelled “meaning structures 1.”

Decoding, the process by which recipients interpret the messages, is equally significant. Here, the recipient’s understanding is influenced by their own meaning structures, referred to as “meaning structures 2.”

Meaning structures consist of “frameworks of knowledge” and “relations of production.” While technical infrastructure considerations are acknowledged, Hall primarily focuses on how cultural factors shape the message.

A “framework of knowledge” refers to the understanding, beliefs, and assumptions that individuals or groups possess within a particular cultural context. This includes shared cultural norms, values, ideologies, and worldviews that shape how people make sense of the world around them. For example, in a society where individualism is highly valued, people may interpret media messages through the lens of personal freedom and autonomy.

On the other hand, “relations of production” refer to the social and economic structures that influence how media messages are produced and distributed. This includes the relationships between media producers, advertisers, regulators, and audiences, and the broader political and economic systems in which they operate. For instance, media ownership structures, advertising revenue models, and government regulations all shape the content and dissemination of media messages.

Together, these two components—frameworks of knowledge and relations of production—help to shape the cultural and social context in which media messages are encoded and decoded. They influence both the content of the messages and how audiences interpret and respond to them.

In sum, Hall’s (1980) model offers a nuanced understanding of communication, recognizing the dynamic role of cultural context in shaping meaning. It challenges the traditional view of communication as a one-way process and emphasizes the active role of both producers and audiences in creating and interpreting media messages.

An Example in Practice

Let’s consider a television advertisement for a luxury car targeting two different audiences: affluent professionals and budget-conscious families and see how the encoding and decoding model might offer insights into how it can be understood.

In the encoding process, the advertising team meticulously crafts the message to appeal to their target demographics. For affluent professionals, the ad might emphasize the car’s sleek design, cutting-edge technology, and performance capabilities. This reflects the meaning structures of the sender, influenced by perceptions of success, status, and luxury.

On the other hand, for budget-conscious families, the ad might highlight the car’s spacious interior, fuel efficiency, and safety features. Here, the meaning structures of the sender are shaped by values of practicality, affordability, and safety.

Now, let’s move to the decoding process. An affluent professional watching the ad may interpret it as a symbol of prestige and success, reinforcing the existing meaning structures associated with luxury and status. Conversely, a budget-conscious family might view the same ad and see the car as a practical and reliable transportation option, aligning with their meaning structures centred around affordability and utility.

In this example, we see how the meaning structures of both the sender/encoder (the advertising team) and the receiver/decoder (the audience) influence the creation and interpretation of the message. The cultural context, including social class, values, and beliefs, significantly shapes how the message is encoded and decoded, ultimately impacting its effectiveness in resonating with the intended audience.

Audience Positions

Once we recognize the “asymmetry” between the intended and received message, as Hall (1980) points out, attributed to the disparities between “meaning structures 1” and “meaning structures 2,” we can delve into various audience interpretations of media texts.

Hall (1980) delineates three audience positions for decoding any media text.

The Dominant-Hegemonic Position: In this position, audiences largely align with the intended message conveyed by the dominant ideologies and values of society. They accept and internalize the message without question, reinforcing the status quo.

Key questions that might be asked to untangle this decoding include:

- How does the text or message reinforce widely accepted ideas or norms without questioning them?

- What emotions or reactions does the encoder intend to evoke?

- What would it look like to accept this uncritically?

The Negotiated Position: Audiences in this position engage with the media text critically. They accept some aspects of the message while rejecting others, negotiating meaning based on their own beliefs, experiences, and values. This position allows for some degree of resistance or reinterpretation of the dominant discourse.

Key questions that might be asked to better understand this approach include:

- Which aspects of the text might audiences agree with?

- Which ones might they find questionable or ambiguous?

- What would a position where the audience agrees partially with the message look like?

- How might this response be situated in specific beliefs, experiences, or values?

The Oppositional Position: Audiences actively resist and reject the intended message, often challenging the dominant ideologies and values embedded within the media text. They interpret the message through the lens of alternative perspectives and counter-narratives, reflecting dissent and opposition to the prevailing social order. This involves not only opposition but also action, as individuals engage critically with media content and may seek to enact change in the real world based on their interpretations.

Key questions that might be asked to situate this interpretation include:

- How might the audience reinterpret or subvert the message to challenge or diverge from dominant ideologies or narratives?

- What alternative perspectives or counter-narratives could the audience adopt to decode the message in opposition to the intended meaning?

- In what ways can the audience actively resist or reject the encoded message, and what strategies do they employ to advocate for alternative viewpoints to induce social change?

Hall himself, along with other researchers at the Birmingham Centre, contributed to the development and testing of this model through empirical studies and critical analysis of media texts. For example, David Morley’s The Nationwide Audience (1980) tested Hall’s segregation of audience positions. Morley (1992) praised how Hall’s model allowed for decoding media messages and sparked emphasis on a new phase of qualitative audience research, focusing on gender realities and media consumption.

An Example in Practice

Let’s examine how different audience positions might interpret a campaign promoting gender equality in the workplace, emphasizing the importance of equal pay, opportunities for career advancement, and combating workplace harassment. The analysis is summarized in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1

Decoding Positions for a Gender Equality Campaign in the Workplace

| Audience Decoding Position | Interpretation |

| Dominant- Hegemonic | How does the text or message reinforce widely accepted ideas or norms without questioning them?

|

What emotions or reactions does the encoder intend to evoke?

|

|

What would it look like to accept this uncritically?

|

|

| Negotiated | Which aspects of the text might audiences agree with?

|

Which ones might they find questionable or ambiguous?

|

|

What would a position where the audience agrees partially with the message look like?

|

|

How might this response be situated in specific beliefs, experiences, or values?

|

|

| Oppositional | How might the audience reinterpret or subvert the message to challenge or diverge from dominant ideologies or narratives?

|

What alternative perspectives or counter-narratives could the audience adopt to decode the message in opposition to the intended meaning?

|

|

In what ways can the audience actively resist or reject the encoded message, and what strategies do they employ to advocate for alternative viewpoints to induce social change?

|

In this example, we see how different audience positions can lead to diverse interpretations of a campaign advocating for gender equality in the workplace. Each position reflects varying degrees of acceptance, negotiation, or opposition to the dominant narratives surrounding gender equity and corporate feminism, highlighting the complexities of addressing social issues within broader socio-political contexts.

Connections to Why We Study Communications

Connecting back to Chapter 1, encoding and decoding, a primary focus of this chapter, offers great insights into four crucial aspects of why we study communications. Firstly, it illuminates the intricate process of identity formation and interpersonal dynamics in shaping our sense of self and understanding others. For example, Hall’s (1980) encoding and decoding model further clarifies how individuals negotiate meanings within cultural contexts, highlighting the interconnectedness fostered through communication processes. Secondly, the encoding and decoding model (Hall,1980) extends into the realm of representation, revealing how media platforms facilitate the projection of individual and collective identities. By examining how messages are encoded by producers and decoded by audiences, we gain insights into the construction and dissemination of societal narratives and norms. Thirdly, encoding and decoding (Hall,1980), play a pivotal role in cultivating civic engagement and democratic functioning. Understanding how messages are constructed, interpreted, and disseminated is crucial for participating effectively in public discourse and shaping societal agendas. Finally, encoding and decoding (Hall,1980) sheds light on power dynamics inherent in discourse construction and the perpetuation of societal norms. By analyzing how meanings are encoded and decoded within communication processes, we gain insights into the mechanisms by which power is negotiated and contested within society.

Limitations

The fields of critical theory, cultural studies, and encoding and decoding specifically, have long been central to the examination of power dynamics, social structures, and communication processes within contemporary society. Rooted in diverse philosophical traditions and methodologies, these frameworks offer invaluable insights into the complexities of culture, ideology, and meaning-making. However, like any theoretical approach, they are not without their limitations.

For example, critical theory encompasses a range of philosophical traditions, including Western European and Marxist thought, leading to diverse interpretations and applications. This diversity can sometimes result in conflicting perspectives within the field (Ryoo & McLaren, 2010).

Moreover, while critical theory and cultural studies has often emphasized using theory for action, some critics contend that the practical implications of critical theory can sometimes be unclear, leading to challenges in translating theoretical insights into actionable social change (Griffin et al., 2023; Ryoo & McLaren, 2010).

Critiques of Stuart Hall’s encoding and decoding model often center on two main points. Firstly, critics highlight the subjective nature of interpretation inherent in the model. This subjectivity arises from individuals’ unique backgrounds and cultural perspectives, leading to diverse interpretations of media texts (Aligwe, Nwafor, & Alegu, 2018). Consequently, interpretations may not always align neatly with the three proposed decoding positions, challenging the notion of fixed and stable decoding modes (Xie et al., 2022).

Secondly, critics have pointed out that the theory’s focus on individual decoding processes often neglects broader macro perspectives. Although there have been efforts to adopt a more macroscopic approach, the theory’s emphasis on micro-level interactions may overlook larger societal and cultural factors that influence media reception. This limitation restricts its ability to analyze complex media phenomena and provide comprehensive explanations for media effects (Aligwe, Nwafor, & Alegu, 2018).

Overall, these critiques underscore the need for a more nuanced understanding of audience reception processes in media analysis, recognizing the dynamic and multifaceted nature of interpretation within Hall’s (1980) model.

Summary and Takeaways

Critical theory and cultural studies offer invaluable frameworks for understanding media, culture, and power dynamics. Stuart Hall’s encoding and decoding model illuminates how meaning is constructed and negotiated within media texts, highlighting the agency of audiences in interpreting messages. Despite their limitations, these approaches are still crucial for critiquing contemporary media landscapes and addressing complex societal issues.

Key chapter takeaways include:

- Critical theory and cultural studies offer indispensable insights into the intersections of media, culture, and society. Originating from the Frankfurt School and further developed by scholars like Stuart Hall, they provide essential tools for analyzing power dynamics, ideologies, and the production of cultural meaning within capitalist societies.

- Understanding the historical development of critical theory and cultural studies illuminates their significance within communication studies. From the Frankfurt School’s critique of mass culture to Hall’s encoding and decoding model, these foundational concepts provide a nuanced understanding of how culture operates as a site of struggle and negotiation.

- Hall’s encoding and decoding model and the delineation of audience positions shed light on how individuals interpret and engage with media texts. Recognizing the diversity of audience responses, from alignment with dominant ideologies to active resistance, highlights the complex interplay between media messages, cultural contexts, and societal dynamics.

References

Adorno, T. W., & Horkheimer, M. (2019). The culture industry: Enlightenment as mass deception. In Philosophers on film from Bergson to Badiou: A critical reader (pp. 80-96). Columbia University Press.

Aligwe, H. N., Nwafor, K. A., & Alegu, J. C. (2018). Stuart Hall’s encoding-decoding model: A critique. World Applied Science Journal, 36, 1019–1023.

Celikates, R., & Flynn, J. (2023). Critical theory (Frankfurt School). In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2023 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/critical-theory/

Corradetti, C. (2012). The Frankfurt school and critical theory. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/critical-theory-frankfurt-school/

eCampusOntario. (2018). Communication for business professionals. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/commbusprofcdn/chapter/1-2/

Griffin, E., Ledbetter, A., Sparks, G. (2023). A first look at communication theory (11 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT press.

Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/Decoding. In C. Greer (Eds.), Crime and Media: A Reader (1st ed., pp 51–61.). Routledge.

Hsu, H. (2017, July 17). Stuart Hall and the rise of cultural studies. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/stuart-hall-and-the-rise-of-cultural-studies

Johnson, A. S. (2020, October 27). The Birmingham School of Cultural Studies. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.44

Lave, J., Duguid, P., Fernandez, N., & Axel, E. (1992). Coming of age in Birmingham: Cultural studies and conceptions of subjectivity. Annual Review of Anthropology, 21, 257–282.

Media Texthack Team. (2014). Media studies 101. BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/mediastudies101/

Morley, D. G. (1980). The nationwide audience. British Film Institute.

Morley, D. G. (1992). Populism, revisionism and the ‘new’ audience research. Poetics, 21(4), 339–344.

Ryoo, J.J., & McLaren, P. (2010). Critical theory. In International Encyclopedia of Education (Third Edition). https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/critical-theory

Xie, Y., Al, M., Bin, I., Agil, S., Shekh, B., & Ang, L. H. (2022). An overview of Stuart Hall’s encoding and decoding theory with film communication. Multicultural Education, 8(1), 190–98.