4 Semiotics (by Cassandra Riabko & Amanda Williams)

Introduction

The concept of semiotics can be understood as the examination of signs and symbols and their role in shaping meaning, representing reality, and interpreting human experiences (Chandler, 2022). Historically, semiotics gained traction as an interdisciplinary field, drawing from disciplines such as linguistics, literature, and sociology (Chandler, 2022). It emphasizes that the meaning of symbols is contingent upon the systems they are embedded within. Essentially, symbols derive their significance from their relationships within a larger system, and when removed from that context, their meaning can shift, adapting to new structures and systems—suggesting ultimately that symbols are fluid.

Semiotics operates within two primary frameworks: first, exploring the relationship between a sign and its meaning, and second, investigating how signs combine to create broader cultural meanings (Chandler, 2022).

Most importantly, semiotics acknowledges that interpretation plays a pivotal role in constructing meaning influenced by personal experiences, values, and cultural backgrounds. To grasp a thorough understanding of culture, individuals are encouraged to hone their interpretive skills as symbol readers and consider contextual factors. By developing these abilities, individuals can delve deeper into cultural artifacts or practices, extracting richer meaning and additional insights (Mills & Barlow, 2012).

Learning Outcomes

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to

- Explain why semiotics is an important part of mass communication and the role it plays in communication studies.

- Recognize the historical context in which semiotics is embedded.

- Understand the foundational principles of semiotics and its limitations.

- Use key terms from semiotics to evaluate the symbolic significance of contemporary examples.

History of Semiotics and Key Thinkers

Semiotics stands as a foundational pillar in the realm of communication theory, particularly connected to media studies and visual communication. While its roots can be traced back to the philosophical musings of St. Augustine in the 4th century (Brown, 2023), it reached a significant milestone in the late 19th century with the seminal contributions of Ferdinand de Saussure, Charles Sanders Peirce, and Roland Barthes (Chandler, 2022).

Ferdinand de Saussure’s contributions laid the groundwork for modern semiotics with his exploration of the signifier and the signified, introducing the notion of the arbitrary nature of signs and the role of social conventions in shaping meaning (Chandler, 2023). In doing so he transformed the common understanding of how language works.

Charles Sanders Peirce expanded upon Saussure’s theories, developing a comprehensive semiotic framework that extended beyond language to encompass all aspects of human life (Atkin, 2023).

Roland Barthes, a prominent French literary theorist and semiotician further expanded the application of semiotics to cultural analysis, particularly through his influential work Mythologies. In this book, Barthes (1957) demonstrated how semiotic analysis could uncover the underlying myths and ideologies embedded within cultural practices and representations. His contribution challenged conventional understandings of meaning and representation, emphasizing the subjective and contingent nature of signification.

Barthes analyzed cultural “texts” through semiotics. Cultural texts refer to media representations such as commercials, videos, film, television, and music. In his work, Barthes (1957) dissected the underlying semiotic structures of everyday objects and rituals, revealing how they reflect and reinforce societal values and ideologies.

According to Barthes (1957), ideologies are not static or fixed; rather, they are dynamic and continuously evolving constructs. These ideologies are perpetuated through various cultural texts, such as language, images, and symbols. Furthermore, these constructs convey specific meanings and messages that reflect the dominant social, political, and economic interests of a particular society or culture. In doing so, they serve to maintain the status quo and reinforce existing power structures within our society.

Together, Saussure, Peirce, and Barthes have significantly shaped the trajectory of semiotics, expanding its scope beyond linguistic analysis to encompass broader cultural and social contexts (Media Studies, 2024). Their collective contributions have paved the way for a deeper understanding of how signs and symbols operate in communication and culture.

Foundational Concepts

There are many foundational concepts in semiotics but the ones that have been most influential for media studies come from Saussure and Barthes and are expanded below.

Language and Parole

Saussure viewed language as a sign system, helping semiotics to extend its scope beyond language. Saussure’s distinction between langue and parole is fundamental in understanding his linguistic theory. Langue refers to the underlying system of language, encompassing the rules, structures, and conventions shared by a speech community. It forms the foundation for communication, providing the framework within which individual utterances are comprehensible (Media Studies, 2024). On the other hand, parole refers to the actual instances of speech or writing produced by individuals within that community. Parole represents the application of langue in specific communicative acts and is characterized by its variability and contextual dependence (Media Studies, 2024). While langue provides the structural framework for language, parole reflects the dynamic and diverse expressions of language in everyday usage.

Saussure’s focus was not on studying a specific language or the linguistic behaviours of individuals within a particular speech community. Instead, he aimed to analyze language as a whole and uncover the underlying systems, rules, and conventions that govern its functioning (Media Studies, 2024).

An Example in Practice

In the English language, langue encompasses the structured system of grammar, vocabulary, syntax, and semantics governing communication within the English-speaking community. This includes rules like subject-verb agreement, sentence structure, and word order, with phonological rules dictating pronunciation and syntactic rules governing sentence formation. For instance, English speakers adhere to these conventions when constructing meaningful sentences.

Conversely, parole refers to the actual instances of spoken or written communication produced by individuals within the community. It embodies the variability, creativity, and context-dependent nature of language use. While English provides grammatical guidelines, individuals may vary sentences in vocabulary, tone, and style based on their communicative intent, personal inclinations, or situational context, illustrating the dynamic nature of language in everyday communication.

The Sign

Saussure’s theories on language structure pave the way for his broader contributions to semiotics, shedding light on the fundamental principles that govern the study of signs and their role in communication and understanding.

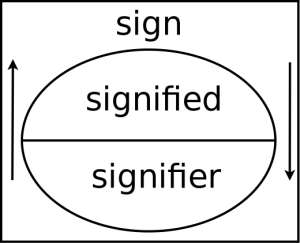

To Saussure, signs are pervasive in our surroundings, and essential to how we interpret the world. In his framework, signs consist of two essential parts: the signified and the signifier (Media Studies, 2024).

The signified refers to the mental concept or image associated with a sign, encompassing the characteristics and meaning attributed to the represented concept or idea (Media Studies, 2024).

In contrast, the signifier represents the physical form of the sign, including words, images, or symbols used to convey a particular concept or idea (Media Studies, 2024). These are demonstrated in Figure 4:1 below.

Figure 4.1

Saussure’s Conceptualization of the Sign

Credit: “Sign” by Mount Royal University

An Example in Practice

When I say or write the word “tree” a mental image of what this is comes to mind. It could look like Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2

Image of Tree

Credit: “Tree” by Mount Royal University

The signified refers to the mental concept or image associated with the signifier, embodying the characteristics and meaning we attribute to a tree. For instance, we visualize a tree with a trunk, leaves, and roots.

Conversely, the signifier is the tangible representation (visible or audible aspect) of the sign, such as the word ”tree” in English.

Together, the signifier and signified constitute the sign, forming a unit of meaning that represents the concept of a tree.

This is outlined in Table 4.1 below.

Table 4:1

Tree as a sign

| SIGNIFIED + | mental concept of what you think a tree is |

| SIGNIFIER | the word tree (letters & sound) |

| = SIGN | a tree |

The Arbitrariness of the Sign

Saussure not only identified the parts of the sign but emphasized how arbitrary they were (Chandler, 2024). The concept of arbitrariness posits that there is no inherent connection between the linguistic sign (the combination of a signifier and a signified) and its meaning; rather, this relationship is purely conventional and established through social agreement within a given linguistic community.

For example, Saussure posited that since each language assigns its name to the mental concept of a tree, the relationship between the physical form of the sign and its meaning is arbitrary. There’s no inherent reason why the arrangement of letters in “tree” should evoke the image of a tree—it’s a convention learned and accepted over time. Moreover, the mental concept of a tree may vary among individuals.

What made Saussure’s treatment of arbitrariness so novel was his insistence on its centrality within the structure of language. While earlier scholars, such as Aristotle and Plato, had touched upon the idea of arbitrariness to some extent, Saussure elevated it to a foundational principle of linguistic analysis (Chandler, 2022). He argued that the arbitrariness of signs extended not only to spoken language but also to written language, challenging the notion that written symbols inherently represent their corresponding sounds or concepts.

By highlighting the socially constructed nature of linguistic signs, he paved the way for a deeper understanding of the role of social and cultural factors in shaping language.

An Example in Practice

An example that illustrates the arbitrariness of signs is the word “dog” in the English language. The combination of the letters d-o-g has no inherent connection to the furry, four-legged animal it represents.

Figure 4. 3

Image of a dog

Credit: “Dog” by LuAnn Snawder Photography © 2012 CC BY-ND 2.0

The sound “dog” could have been associated with an entirely different concept or object if language users had agreed upon it. For instance, in another language or culture, the same animal might be represented by a completely different set of sounds or symbols.

To demonstrate how the relationship between the signifier and the signified could be otherwise, imagine a hypothetical scenario where English speakers decided to change the word for “dog” to “flork.” In this alternative linguistic system, the signifier “flork” would now represent the concept of a dog, while the previous signifier “dog” might take on an entirely different meaning or become obsolete. This example highlights the arbitrary nature of linguistic signs and how they are subject to change based on social agreement and convention within a linguistic community.

Figure 4.4

Image of dog/flork

Credit: “Dog” by LuAnn Snawder Photography © 2012 CC BY-ND 2.0

Third order signification

Building upon the work of Saussure extensively, Barthes employed the concept of third-order signification in his analysis of cultural texts and social phenomena. He explored how signs, symbols, and cultural artifacts convey deeper layers of meaning beyond their immediate referents, highlighting the ideological implications embedded within them.

One notable example of Barthes’ application of third-order signification is found in his analysis of advertisements and popular culture. In his seminal work Mythologies, Barthes (1957) examined how seemingly mundane objects and images, such as advertisements for soap or cars, function as carriers of ideological messages that reflect and reinforce dominant social values and norms. Through his analysis, Barthes (1957) revealed how these cultural texts operate as signs that signify not only the products being advertised but also broader social constructs, power dynamics, and cultural myths.

Furthermore, Barthes’ (1957) concept of myth can be seen as a manifestation of third-order signification. He argued that cultural myths function as a form of symbolic language through which society communicates and naturalizes ideological beliefs and social hierarchies. By deconstructing these myths, Barthes (1957) aimed to expose the underlying ideological mechanisms at play and challenge the taken-for-granted assumptions embedded within them.

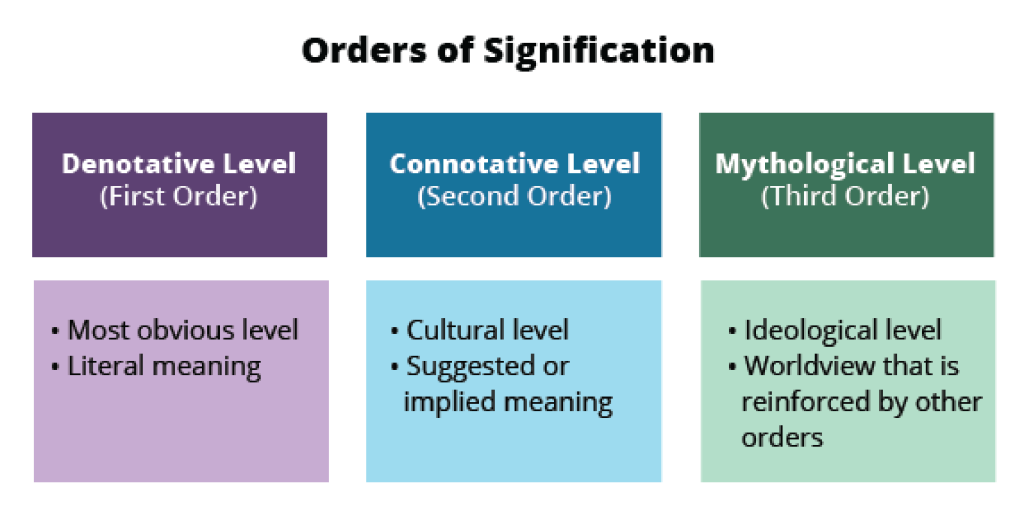

Below, each of the three levels of signification is broken down.

Denotative Meaning (First Level of Meaning): The denotative meaning, as conceptualized by Barthes (1957), represents the fundamental layer of signification in communication. It pertains to the straightforward and literal interpretation of signs or symbols without delving into deeper ideological or symbolic content. In essence, it captures the surface-level meaning of a sign, devoid of any underlying connotations or cultural associations.

This level of meaning focuses solely on what is directly observable or explicitly communicated by the sign. It encompasses the basic identification of objects, people, or actions depicted in an image or described in a text, without considering the broader context or implicit messages embedded within them. Therefore, the denotative order serves as the foundation upon which higher levels of signification, such as connotation and myth, are built.

In practical terms, identifying the denotative meaning of a sign involves recognizing its most apparent attributes or characteristics and understanding them at face value. This may include interpreting visual elements, such as colours, shapes, and objects, or understanding the literal meanings of words or phrases without inferring additional symbolism or significance.

Connotative Meaning (Second Level of Meaning): This second order or signification, as described by Barthes (1957), delves into the cultural significance behind the literal elements of an image or text. Unlike the denotative level, which deals with straightforward meanings, the connotative meaning explores the implied or suggested meanings that are shaped by societal and personal interpretations (Barthes, 1957, p. 91). In this context, the sign loses its direct historical reference (Griffin, Ledbetter, & Sparks, 2023) and takes on additional layers of meaning that are subject to cultural context and individual perception. Barthes (1957) argues that culture becomes “a noble, universal thing, placed outside social choice” (p. 81).

At the heart of the connotative order lie the social and personal interpretations that individuals assign to symbols or experiences. Although Barthes does not explicitly define social connotations, the word “social” recurs 43 times in his work Mythologies (Barthes, 1957), often linked to terms like convention (p. 6), phenomenon (p. 10, p. 27), attributes (p. 27), and form (p. 28). These interpretations are shaped by norms, values, beliefs, as well as personal experiences and emotions. Thus, while cultural connotations focus on specific meanings associated with symbols or practices within a particular culture, social ideals encompass broader societal standards or expectations concerning desirable attributes, behaviours, or outcomes.

Mythological Meaning (Third Level of Meaning): The third order of signification, known as myth (Barthes,1957), delves into the realm of deeply ingrained cultural assumptions and societal worldviews, often regarded as the normative fabric of society. In this context, Barthes explores how cultural myths operate as powerful tools that transform historical or cultural meanings into seemingly naturalized concepts, thereby exerting a significant influence on societal perceptions and collective consciousness (Barthes, 1957). Through the process of myth-making, Barthes contends that these cultural narratives not only shape our understanding of reality but also reinforce existing power structures and social hierarchies. By analyzing how myths are constructed and disseminated within society, Barthes reveals the underlying mechanisms through which dominant ideologies are perpetuated and normalized, thus emphasizing the complex interplay between language, culture, and power in shaping human thought and behaviour.

Via myth, Barthes (1957) demonstrated how seemingly mundane objects and cultural practices (such as wrestling, films, photos, cars, food, and even strip-teases) can be elevated to the status of myth, thereby reinforcing existing power dynamics. By presenting these elements as natural and timeless, myth obscures the historical and cultural contingencies that underpin them, making them appear beyond challenge or change.

Moreover, Barthes (1957) argued that myth works to neutralize dissent and resistance by framing alternative perspectives as deviant or inconsequential. It marginalizes counter-narratives, delegitimizes opposing viewpoints, and suppresses dissenting voices by portraying them as aberrations from the norm. This process of neutralization operates subtly but effectively, shaping public discourse and limiting the range of acceptable ideas and actions within society.

Furthermore, myth perpetuates the status quo by fostering a sense of collective identity and belonging based on shared myths and cultural narratives. These shared myths serve to unify communities, reinforce social cohesion, and justify existing power structures. By framing certain groups or individuals as deserving of privilege and authority, while others are portrayed as inferior or subordinate, myth reinforces social hierarchies and inequalities. Often these shared myths take the form of stereotypes. Stereotypes can be defined as oversimplified generalizations or assumptions about groups of people based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, or nationality. They often ignore individual differences and can perpetuate prejudice and discrimination.

In essence, Barthes’ (1957) exploration of myth, within the framework of semiotics, highlights the dual role it plays in the perpetuation of power dynamics. It naturalizes existing power structures by presenting them as inherent and inevitable, while simultaneously neutralizing dissent and resistance by marginalizing alternative perspectives. By fostering a sense of collective identity and belonging based on shared narratives, myth reinforces the status quo and perpetuates societal norms and inequalities. Through the critical lens of semiotics, scholars can unravel how myth shapes our understanding of power and perpetuates existing social hierarchies.

In Barthes’s (1957) analysis, he cites a specific example from the 1960s involving a magazine cover of Paris-Match. The cover depicts a black man wearing a French military uniform and saluting. Barthes interprets this image as a constructed narrative or “motivated myth” that serves to convey a particular message or ideology. In this case, the image is intended to establish the myth “that France is a great Empire, that all her sons, without any colour discrimination, faithfully serve under her flag, and that there is no better answer to the detractors of an alleged colonialism than the zeal shown by this [solider]” (Barthes, 1957, p. 155). This narrative seeks to normalize the depicted relations by associating the black man, representative of the struggles of those affected by colonialism, with the symbol of the military uniform. Through the conjuncture of meaning represented by the black man and the form symbolized by the army uniform, the image constructs a myth that reinforces certain societal beliefs and values. In this instance, the assertion that being a soldier is a uniform experience for all in France contradicts lived realities, where factors such as class and race undeniably influence one’s experience.

Below is a visual summary of Barthes’(1957) main ideas.

Figure 4.5

Image of Third-Order Signification

Credit: “Orders of Signification” by Mount Royal University

A useful way to summarize these concepts and questions you might ask of a text can be found below in Table 4:2.

Table 4.2

Analytic framework for exploring Third-Order Signification in Visual Images

| Level of Signification | Questions for Analysis |

| Denotative Meaning | What is the straightforward or explicit meaning conveyed by the visual elements in the image?*Exclude emotions or feelings that could be subject to interpretation. Focus on elements that are universally observable when examining the visual.Example: This image depicts [describe objects/people featured, mention any present words or text, describe the colour scheme, and note the placement and size of objects/words]. |

| Connotative Meaning | What cultural meanings or associations are suggested by the visual elements?*You could do some research on the symbols in this case to make your analysis more fulsome.Example: In an advertisement for a perfume, the visual elements might include a sophisticated woman in an elegant dress, standing on a Parisian balcony with the Eiffel Tower in the background. These elements suggest cultural meanings of romance, luxury, and cosmopolitan sophistication. The association with Paris, often considered the “City of Love,” evokes ideas of romantic escapism and high fashion. This portrayal links the perfume to a glamorous, desirable lifestyle, suggesting that wearing it will enhance one’s allure and sophistication. |

| What societal values or meanings are likely proposed by the visual elements?Examples: Common social ideals perpetuated especially in Western media concern the following: ideal beauty standards (portraying flawless skin, slim bodies, and symmetrical features as ideals to aspire to); success and wealth (luxurious lifestyles, expensive possessions, and extravagant experiences, suggesting that success and happiness are synonymous with material wealth); family and relationships (idealized images of family life and relationships, emphasizing concepts such as love, unity, and togetherness); and,independence and individuality (promote the societal ideal of authenticity and self-fulfillment through personal empowerment) | |

| How do you personally interpret the combination of visual elements in the advertisement? What personal thoughts or feelings does the ad evoke about what is being conveyed?Example: When I see an advertisement for a tropical vacation, with images of serene beaches, clear blue waters, and luxurious resorts, it evokes a sense of calm and desire for escape. Personally, I interpret these visual elements as a promise of relaxation and a break from the stresses of daily life. The ad makes me feel that investing in such a vacation would provide me with rejuvenation and happiness. | |

| MythicMeaning | How do the visual elements convey messages that reflect dominant social values and norms about what you should want and how you should feel?Example:In a luxury car advertisement, the sleek design, spacious interiors, and advanced technology features are prominently displayed. These visual elements convey messages that owning such a car is a symbol of success and sophistication. It reflects dominant social values that equate material wealth with personal achievement and happiness, suggesting that you should desire this car to feel fulfilled and respected in society. |

| What power dynamics or social hierarchies are implicit in the representation of these symbols? Whose perspectives or experiences are being centred or marginalized?Example: An advertisement for a high-end fashion brand prominently features a young, white, slim woman in expensive clothing. This representation centers the perspectives and experiences of those who fit this narrow definition of beauty and wealth, while marginalizing people of different races, body types, and socioeconomic statuses. The ad implicitly reinforces social hierarchies where wealth and conventional beauty are equated with higher social status and desirability. | |

| Do the portrayals of these symbols contain underlying biases or stereotypes? If so, how do these biases contribute to shaping social identities and cultural narratives, effectively normalizing and naturalizing them within society?Example: An advertisement for cleaning products shows a woman happily cleaning her home, reinforcing the stereotype that domestic chores are primarily women’s responsibilities. This portrayal contains an underlying gender bias that normalizes the idea that women should take on the majority of household tasks. By consistently depicting women in these roles, such ads contribute to shaping social identities and cultural narratives that perpetuate traditional gender roles, making them seem natural and expected in society. |

An Example in Practice

Below is an ad explored in some detail by Hodgson (2017) which allows us to appreciate the use of Barthes concepts in action.

Figure 4. 6

Ad from Coca-Cola’s Christmas branding campaign: “The holidays are coming”

Credit: Hodgson (2017)

The three levels of signification can be applied to this ad given additional insights into its significance from a design, social and ideological perspective.

Let’s start with the denotative or the literal level.

Table 4.3

Denotative Meaning of “The holidays are coming” ad

| Denotative Meaning | Analysis |

| This ad is an image which portrays a red transport truck with white lights, surrounded by swirling stars, and featuring Santa Claus enjoying a Coca-Cola beverage. The tagline “Holidays are coming” is present, along with three soda bottles. Red and white colours dominate the image, and the words “Coca-Cola” are prominently displayed. |

Next, we can explore the connotative which includes the cultural meanings, social ideals, and personal responses to the images.

Table 4.4

Connotative Meaning of “The holidays are coming” ad

| Connotative Meaning | Analysis |

| Cultural Meanings or Associations | The swirls of stars suggest the magic and wonder of the holidays, evoking feelings of excitement and anticipation associated with the festive season.Santa Claus symbolizes the spirit of generosity and goodwill traditionally linked with Christmas, tapping into nostalgic emotions and cultural traditions surrounding gift-giving and family gatherings.The use of red, a colour traditionally associated with Christmas, symbolizes warmth, passion, and vitality, contributing to the festive atmosphere and creating a sense of joy and excitement. |

| Societal Values or Meanings | The advertising reinforces the cultural significance of holiday traditions, emphasizing the importance of togetherness, generosity, and shared experiences with loved ones.The ad promotes consumerism by associating Coca-Cola with cherished holiday moments, suggesting that purchasing and consuming the beverage can enhance the holiday experience and create lasting memories.The use of familiar holiday symbols like Santa Claus and red imagery appeals to societal ideals of tradition, nostalgia, and emotional connection, reinforcing the brand’s connection with consumers during the holidays. |

| Personal Interpretation | As a viewer, I interpret the advertisement as invoking a sense of warmth, joy, and nostalgia associated with the holiday season. The imagery of Santa Claus and the vibrant red colour scheme evoke fond memories of past holidays and create a festive atmosphere that resonates with me emotionally.The ad suggests that Coca-Cola is not just a beverage but a symbol of holiday cheer and togetherness, prompting feelings of anticipation and excitement for the upcoming festivities.Overall, the combination of visual elements evokes a sense of holiday magic and reinforces the idea of Coca-Cola as an integral part of the holiday tradition, fostering a personal connection with the brand and its message |

Finally, a mythological analysis can involve exploring entrenched values, power dynamics, hierarchies, biases, and stereotypes that seem intrinsic and ordinary but are, in reality, socially constructed and far from natural or normal.

Table 4.5

Mythic Meaning of “The holidays are coming” ad

| Meaning | Analysis |

| How do the visual elements convey messages that reflect dominant social values and norms about what you should want and how you should feel? | The advertisement portrays Coca-Cola as a symbol of joy, togetherness, and holiday cheer, aligning with dominant social values that prioritize happiness and celebration during the festive season. It suggests that consuming Coca-Cola products is desirable and integral to experiencing joy and celebrating holidays, reflecting societal norms around consumerism and the commercialization of festivities. |

| What power dynamics or social hierarchies are implicit in the representation of these symbols? Whose perspectives or experiences are being centred or marginalized? | The advertisement centres the perspective of individuals who can afford and access Coca-Cola products, reinforcing power dynamics that privilege those with economic resources.It marginalizes perspectives from communities with limited access to healthcare and nutrition education, overlooking the potential negative impacts of sugary beverage consumption on public health. Also, the association with Santa Claus perpetuates Western cultural narratives that prioritize consumerist ideals and materialism, potentially marginalizing alternative cultural perspectives. |

| Are there any underlying biases or stereotypes embedded in the portrayal of these symbols? How do they contribute to the construction of social identities or cultural narratives? | The portrayal of Coca-Cola as synonymous with joy and happiness perpetuates biases that equate consumption with fulfillment and well-being, reinforcing consumerist narratives that prioritize material possessions over genuine human connection.This contributes to the construction of social identities that associate happiness and status with the consumption of Coca-Cola products, perpetuating stereotypes about the link between consumerism and personal happiness.The association with Santa Claus may perpetuate stereotypes about Western cultural dominance and the universalization of Western holiday traditions. |

As this example illustrates a look at all three levels of signification can be quite revealing.

Connections to Why We Study Communications

Connecting back to Chapter 1, regarding identity formation, semiotics delves into how signs and symbols contribute to constructing and projecting identities through language, visual imagery, and cultural ideas. Regarding civic engagement, semiotics unveils how signs are employed in political communication to shape public opinion, mobilize citizens, and influence political discourse. Furthermore, semiotics highlight the active role of audiences in interpreting and negotiating the meaning of signs within specific cultural contexts, whether denotative, connotative, or mythic. Lastly, semiotics exposes how signs and symbols perpetuate power differentials and shape societal norms through language, visual imagery, and cultural representations. Overall, semiotics offers critical insights into the complex dynamics of communication, enabling scholars and practitioners to navigate and advocate for social change in our mediated world.

Limitations

Critiques of semiotics highlight several concerns, including its uncritical presentation as a general-purpose tool and subjective nature. Semioticians often do not explicitly address the limitations of their techniques, leading to a perception that semiotics can be universally applied. However, empirical evidence for these interpretations is often lacking, and analyses tend to be impressionistic and unsystematic (Chandler, 2022).

Another limitation revolves around the tendency of semiotics to prioritize structural systems over dynamic processes of audience use. Semiotics may benefit from actually talking to audience members instead of assuming their interpretations based on their skills as an analyst (Chandler, 2022).

Finally, critiques of semiotics also point out that analyses of mythic meaning, as exemplified by the work of Barthes (1957), require a considerable level of skill. Barthes’ approach to dissecting cultural myths involves uncovering the hidden underpinnings embedded within seemingly innocuous cultural artifacts. However, this process demands a deep understanding of cultural codes and conventions, as well as the ability to discern subtle nuances in meaning. As such, effectively applying semiotic analysis to uncover mythic meanings necessitates expertise and interpretive finesse, which may not always be readily accessible to all analysts (Griffin et al., 2023).

Summary

Semiotics, rooted in the study of signs and symbols, delves into how these elements shape meaning, represent reality, and influence human experiences. Emerging in the 19th and 20th centuries as an interdisciplinary field drawing from linguistics, literature, and sociology, semiotics focuses on understanding the relationship between signs and meanings within cultural and social frameworks. Key thinkers such as Ferdinand de Saussure and Roland Barthes have contributed significantly to the development of semiotics theory in communication studies, emphasizing the structural nature of signs and the layers of meaning they convey, providing us with powerful tools for an analysis of language and visuals.

Several takeaways emerged from this chapter:

- Semiotics uncovers the intricate meanings embedded within signs and symbols. It emphasizes the arbitrariness of signs and introduces concepts like third-order signification, challenging conventional interpretations and enriching our understanding of language and culture.

- Semiotics, particularly through myth analysis by Roland Barthes, exposes how power structures are naturalized and perpetuated. Myth universalizes ideas, obscuring historical contexts and neutralizing dissent. Fostering collective identity through shared narratives reinforces social hierarchies and prompts critical inquiry into normalized biases and injustices.

- The value of semiotics lies in its ability to cultivate critical thinking and cultural awareness. It provides a framework for analyzing the dynamic interplay between signs and their social contexts, empowering individuals to decode the symbolic landscape of society. Semiotics fosters a deeper appreciation of cultural diversity by discerning subtle nuances in communication and the social construction of the language and symbols we frequently deploy.

In sum, semiotics offers sophisticated concepts for decoding the symbolic aspects of society. This fosters a better understanding of cultural diversity and encourages a better engagement with the complexities of human expression, representation, and power dynamics.

References

Atkin, A. (2023). Peirce’s theory of signs. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/peirce-semiotics/

Barthes, R. (1957). Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang, 302–06.

Barthes, R. (1977). Image, music, text. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 37(2) 235–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/429854

Brown, T. (2023, August 30). Saint Augustine and the semiotic trinity. Medium. https://medium.com/@tkbrown413/saint-augustine-and-the-semiotic-trinity-4554437d4f40

Chandler, D. (2022). Semiotics: the basics. New York: Routledge.

Clark-Keane, C. (2024, Feb. 26). Ways to use colour psychology in marketing (with examples). WordStream. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2022/07/12/color-psychology-marketing

Gorban, P. (2016) Qualitative extensions and limits of semiotics. International Journal of Communication Research 6(2) 143–151. https://www.ijcr.eu/articole/316_07%20Paul%20GORBAN.pdf

Griffin, E., Ledbetter, A., Sparks, G. (2023). A first look at communication theory (11 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hodgson, S. (2017). Holidays are coming: The Coca-Cola Christmas branding story. Medium. https://medium.com/@Stewart_Fabrik/holidays-are-coming-the-coca-cola-christmas-branding-story-8f08e2be8def

Media Studies. (2024). Introduction to semiotics. https://media-studies.com/semiotics/

Mills, B. & Barlow, D. (2012) Reading media theory (2 ed,). New York: Routledge.