Evidence

Evaluating Quality

Jennifer Lapum; Oona St-Amant; Michelle Hughes; Andy Tan; Arina Bogdan; Frances Dimaranan; Rachel Frantzke; and Nada Savicevic

Evaluating your sources is critical to the process of academic research. One common tool is called CRAAP. Yes, you read that correctly! The CRAAP test is an evaluation tool that helps you determine a source’s quality and provides you with a way to analyze your sources and determine if they are appropriate for your research. You will come across various versions of CRAAP, but for the purposes of this chapter, the acronym stands for:

C: Currency

R: Relevance

A: Authority

A: Accuracy

P: Purpose/point of view

Figure 3.7: Dissecting CRAAP

Time to dissect CRAAP a bit more!

The CRAAP test uses a series of questions that address specific evaluation criteria like the authority and purpose of the source. This test should be used for all of your sources. It is not intended to make you exclude any sources, but to help you analyze how to use them to support your own arguments. You will find that some sources are of such low quality that it wouldn’t be helpful to your argument if you used them. See Table 3.2. for an overview of the CRAAP test.

Table 3.2: Overview of the CRAAP test

| Criteria | Relation to nursing |

|---|---|

|

C = Currency: The timeliness of the information. When was the information published or posted? Based on this date, will the material accurately reflect your topic? Has the information been revised or updated? Does your topic require current information, or will older sources work as well? |

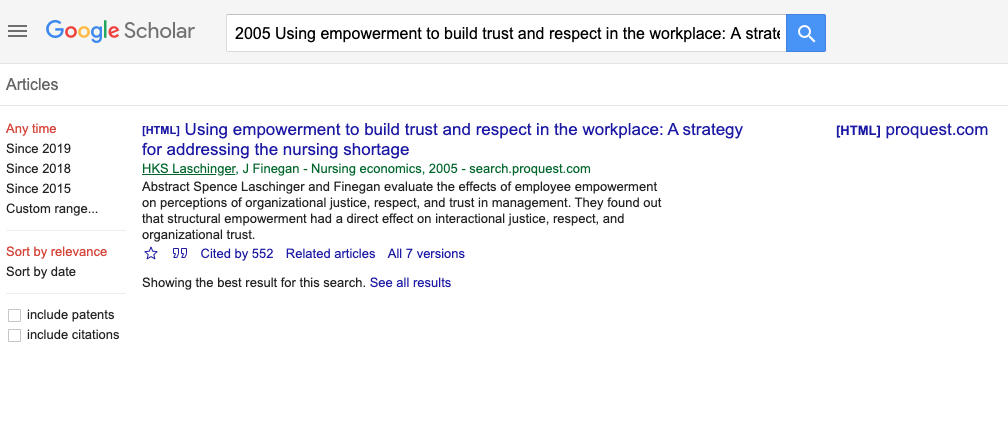

What is considered current and how current does a resource have to be? This is a complex question. Some say a current text was written within five years, and some say within ten years. If currency is not noted in your assignment guidelines, ask your instructor. Currency will vary based on the topic. There are evolutions in knowledge that inform thinking and practices based on the most current research. For example, if you are exploring cannabis use in Canada, the currency of this information is important because so much has changed in the last few years. For this topic, you would probably search for texts produced within the last one or two years to ensure currency. Sometimes, you’ll also need to consider seminal literature. This type of literature refers to a pivotal study or theoretical article that is foundational to a discipline. How do you know if a text is seminal? One clue is when you see the same article cited in the literature over and over again. Frequency of the citation usually indicates that an article has had a major influence. For example, Dr. Heather Laschinger’s nursing work on empowerment from the 1990s and early 2000s has been cited thousands of times. Although this work is older, it is considered seminal in this topic. To find out how many times an article has been cited, search the article title in Google Scholar – this website will indicate how many times the article has been cited. See Figure 3.8 as an example. Determining whether literature is seminal takes experience and becoming familiar with a topic. Early in your career, you may need to consult your instructors to help you determine whether literature is seminal. |

|

R = Relevance: The importance of the information for your needs. Does the information relate to your topic or answer your question? Who is the intended audience? Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e., not too elementary or advanced for your needs or audience)? Have you looked at a variety of sources before determining the ones that you will use?

|

You should consider various factors when considering the relevance of your sources. Does the source align with the topic that you are studying? For example, if you are studying parents’ grieving experiences after their child dies, your sources need to focus on this topic. A source that documents nurses’ grieving experiences after a client dies is not relevant, as the relationships are quite different. Also, if you are exploring the nurse’s role in medical assistance in dying, for example, it is important to consider legislation in the related country and province/territory/state. For example, the nurse’s role in Ontario is different than other locations. You will review sources from a wide variety of locations and written for a wide variety of audiences. You need to consider whether your reader will believe that the sources you have chosen are relevant. |

|

A = Authority: The source of the information. Is the author qualified to write on the topic? Do you trust the author? If applicable, what are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations? Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source? For example: .com .edu .gov .org .net Is the journal or textbook publisher reputable or well known? |

Often, an author with one or more degrees is accepted as being an authority. For example, does the author have a Master of Nursing and/or a PhD in Nursing or a related field? Does the author have experience and/or expertise in the area that they are writing about? Have they published multiple articles in this area? Are they from a reputable university, college, hospital, or healthcare organization? Try Googling the author to find out where they work and their publication record. Depending on your topic, you might also draw upon sources in which the expert is the client or the family. This shift has recently become more common, particularly in Canada, where patients are encouraged to collaborate in health research – this is sometimes required when applying for research funding. There has also been a shift toward incorporating narratives, so patients, families, and students make important contributions to various bodies of literature. It is also important to examine whether the publisher and/or journal is reputable, particularly in this era of open access publishing, where access to many journals is free – but the quality of these journals is sometimes questionable. Open access can be of great benefit to students who don’t have access to an institutional library database. However, the risk is that many predatory journals are emerging – they may be focused on making money. As a result, the quality of articles published in these journals may be lacking. You need to make sure that the article that you are reading is from a reputable journal. How do you figure this out? Start by Googling the journal name. Find its homepage and check whether the editor and editorial board members are from reputable institutions and whether the journal has a peer-review process (peer review is discussed later in this chapter). You can also check out websites such as: Beall’s List of Predatory Journals and Publishers. Your university librarians can also help you figure out whether the article is from a reputable journal. |

|

A= Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content. Where does the information come from? Is the information supported by evidence? Has the information been reviewed or refereed? Can you verify any of the information in another source or from personal knowledge? Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion? Are there spelling, grammar, or typographical errors? |

You must evaluate and ensure that your researched sources are both reliable and truthful. Again, assess whether the article underwent peer review. Usually, the “About” or “Journal Info” section of the homepage will specify whether the journal has a peer-review process. Unfortunately, some predatory journals and publishers are getting smart and falsely claiming to use a peer-review process. Check out the editorial board members. Are they real people from real institutions? Check out the authors’ citations if the article refers to claims or facts that seem questionable. Also, if the article presents the results of a study, you will need to evaluate the research methods. You will develop the skills to evaluate research methods in a research course as part of your nursing program. |

|

P = Purpose/Point of view: The reason the information exists. What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain, or persuade? Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear? Do they identify the overall goal, research aim, or paper’s objectives? Is the information fact, opinion, or propaganda? Does the point of view appear objective and impartial? Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional, or personal biases? For example, are they trying push their own agenda? Do they have a bias? Are they trying to convince you to buy something? |

These are all important questions to consider when you are evaluating the sources that you plan to use when writing a paper. Your source’s purpose should be clear and informative. You should avoid incorporating sources that have any kind of underlying bias. Avoid journal sites with click-bait . Many of you will be familiar with this from social media. Usually, these types of sites are trying sell something and/or push an agenda related to a particular topic. |

Figure 3.8: Search on how many times an article has been cited

Checklist Source Evaluation

Here is a checklist that you can use to evaluate your sources:

- Have you applied the CRAAP test to your sources?

- Is the type of source appropriate for your purpose? Is it a high-quality source or one that needs to be looked at more critically?

- Can you establish that the author is credible and the publication is reputable?

- Does the author support ideas with specific facts and details that are carefully documented? Is the source of the author’s information clear? (When you use secondary sources, look for sources that are not too removed from primary research.)

- Does the source include any factual errors or instances of faulty logic?

- Does the author leave out any information that you would expect to see in a discussion of this topic?

- Do the author’s conclusions logically follow from the evidence that is presented? Can you see how the author got from one point to another?

- Is the writing clear and organized, and is it free from errors, clichés, and empty buzzwords? Is the tone objective, balanced, and reasonable? (Be on the lookout for extreme, emotionally charged language.)

- Are there any obvious biases or agendas? Based on what you know about the author, are there likely to be any hidden agendas?

- Are graphics informative, useful, and easy to understand? Are websites organized, easy to navigate, and free of clutter like flashing ads and unnecessary sound effects?

- Is the source contradicted by information found in other sources? (If so, it is possible that your sources are presenting similar information but taking different perspectives, which requires you to think carefully about which sources you find more convincing and why. Be suspicious, however, of any source that presents facts that you cannot confirm elsewhere.)

Activities: Check Your Understanding

Attribution statement

The activities were created by the authors.

Unless otherwise noted, all other content was remixed with our own original content, and adapted from:

Write Here, Right Now by Dr. Paul Chafe, Aaron Tucker with chapters from Dr. Kari Maaren, Dr. Martha Adante, Val Lem, Trina Grover and Kelly Dermody, under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Download this book for free at: https://pressbooks.library.ryerson.ca/writehere/

The checklist course evaluation was adapted from:

Writing for Success 1st Canadian Edition by Tara Horkoff is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Download for free at: https://opentextbc.ca/writingforsuccess/

Media Attributions

- Number of times article has been cited

Learning Objectives

- List common causes of stress for college students.

- Describe the physical, mental, and emotional effects of persistent stress.

- List healthy ways college students can manage or cope with stress.

- Develop your personal plan for managing stress in your life.

We all live with occasional stress. Since college students often feel even more stress than most people, it’s important to understand it and learn ways to deal with it so that it doesn’t disrupt your life.

Stress is a natural response of the body and mind to a demand or challenge. The thing that causes stress, called a stressor, captures our attention and causes a physical and emotional reaction. Stressors include physical threats, such as a car we suddenly see coming at us too fast, and the stress reaction likely includes jumping out of the way—with our heart beating fast and other physical changes. Most of our stressors are not physical threats but situations or events like an upcoming test or an emotional break-up. Stressors also include long-lasting emotional and mental concerns such as worries about money or finding a job. Take the Stress Self-Assessment.

Stress Self-Assessment

Check the appropriate boxes.

| Daily | Sometimes | Never | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel mild stress that does not disrupt my everyday life. | |||

| 2. I am sometimes so stressed out that I have trouble with my routine activities. | |||

| 3. I find myself eating or drinking just because I’m feeling stressed. | |||

| 4. I have lain awake at night unable to sleep because I was feeling stressed. | |||

| 5. Stress has affected my relationships with other people. |

Write your answers.

-

What is the number one cause of stress in your life?

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

-

What else causes you stress?

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

-

What effect does stress have on your studies and academic performance?

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

-

Regardless of the sources of your own stress, what do you think you can do to better cope with the stress you can’t avoid?

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

What Causes Stress?

Not all stressors are bad things. Exciting, positive things also cause a type of stress, called eustress. Falling in love, getting an unexpected sum of money, acing an exam you’d worried about—all of these are positive things that affect the body and mind in ways similar to negative stress: you can’t help thinking about it, you may lose your appetite and lie awake at night, and your routine life may be momentarily disrupted.

But the kind of stress that causes most trouble results from negative stressors. Life events that usually cause significant stress include the following:

- Serious illness or injury

- Serious illness, injury, or death of a family member or loved one

- Losing a job or sudden financial catastrophe

- Unwanted pregnancy

- Divorce or ending a long-term relationship (including parents’ divorce)

- Being arrested or convicted of a crime

- Being put on academic probation or suspended

Life events like these usually cause a lot of stress that may begin suddenly and disrupt one’s life in many ways. Fortunately, these stressors do not occur every day and eventually end—though they can be very severe and disruptive when experienced. Some major life stresses, such as having a parent or family member with a serious illness, can last a long time and may require professional help to cope with them.

Everyday kinds of stressors are far more common but can add up and produce as much stress as a major life event:

- Anxiety about not having enough time for classes, job, studies, and social life

- Worries about grades, an upcoming test, or an assignment

- Money concerns

- Conflict with a roommate, someone at work, or family member

- Anxiety or doubts about one’s future or difficulty choosing a major or career

- Frequent colds, allergy attacks, other continuing health issues

- Concerns about one’s appearance, weight, eating habits, and so on.

- Relationship tensions, poor social life, loneliness

- Time-consuming hassles such as a broken-down car or the need to find a new apartment

- _______________________________________

- _______________________________________

- _______________________________________

Take a moment and reflect on the list above. How many of these stressors have you experienced in the last month? The last year? Circle all the ones that you have experienced. Now go back to your Stress Self-Assessment and look at what you wrote there for causes of your stress. Write any additional things that cause you stress on the blank lines above.

How many stressors have you circled and written in? There is no magic number of stressors that an “average” or “normal” college student experiences—because everyone is unique. In addition, stressors come and go: the stress caused by a midterm exam tomorrow morning may be gone by noon, replaced by feeling good about how you did. Still, most college students are likely to circle about half the items on this list.

But it’s not the number of stressors that counts. You might have circled only one item on that list—but it could produce so much stress for you that you’re just as stressed out as someone else who circled all of them. The point of this exercise is to start by understanding what causes your own stress as a base for learning what to do about it.

What’s Wrong with Stress?

Physically, stress prepares us for action: the classic “fight-or-flight” reaction when confronted with a danger. Our heart is pumping fast, and we’re breathing faster to supply the muscles with energy to fight or flee. Many physical effects in the body prepare us for whatever actions we may need to take to survive a threat.

But what about nonphysical stressors, like worrying about grades? Are there any positive effects there? Imagine what life would feel like if you never had worries, never felt any stress at all. If you never worried about grades or doing well on a test, how much studying would you do for it? If you never thought at all about money, would you make any effort to save it or make it? Obviously, stress can be a good thing when it motivates us to do something, whether it’s study, work, resolving a conflict with another, and so on. So it’s not stress itself that’s negative—it’s unresolved or persistent stress that starts to have unhealthy effects. Chronic (long-term) stress is associated with many physical changes and illnesses, including the following:

- Weakened immune system, making you more likely to catch a cold and to suffer from any illness longer

- More frequent digestive system problems, including constipation or diarrhea, ulcers, and indigestion

- Elevated blood pressure

- Increased risk of diabetes

- Muscle and back pain

- More frequent headaches, fatigue, and insomnia

- Greater risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular problems over the long term

Chronic or acute (intense short-term) stress also affects our minds and emotions in many ways:

- Difficulty thinking clearly or concentrating

- Poor memory

- More frequent negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, frustration, powerlessness, resentment, or nervousness—and a general negative outlook on life

- Greater difficulty dealing with others because of irritability, anger, or avoidance

No wonder we view stress as such a negative thing! As much as we’d like to eliminate all stressors,however, it just can’t happen. Too many things in the real world cause stress and always will.

Unhealthy Responses to Stress

Since many stressors are unavoidable, the question is what to do about the resulting stress. A person can try to ignore or deny stress for a while, but then it keeps building and starts causing all those problems. So we have to do something.

Consider first what you have typically done in the past when you felt most stressed; use the Past Stress-Reduction Habits Self-Assessment.

Past Stress-Reduction Habits Self-Assessment

On a scale of 1 to 5, rate each of the following behaviors for how often you have experienced it because of high stress levels.

| Stress Response | Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Usually | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Drinking alcohol | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Drinking lots of coffee | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Sleeping a lot | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. Eating too much | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. Eating too little | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. Smoking or drugs | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. Having arguments | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. Sitting around depressed | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9. Watching television or surfing the Web | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10. Complaining to friends | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11. Exercising, jogging, biking | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12. Practicing yoga or tai chi | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13. Meditating | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14. Using relaxation techniques | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15. Talking with an instructor or counselor | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Total your scores for questions 1–10: _______________

Total your scores for questions 11–15: _______________

Subtract the second number from the first: _______________

Interpretation: If the subtraction of the score for questions 11 to 15 from the first score is a positive number, then your past coping methods for dealing with stress have not been as healthy and productive as they could be. Items 1 to 10 are generally not effective ways of dealing with stress, while items 11 to 15 usually are. If you final score is over 20, you’re probably like most beginning college students—feeling a lot of stress and not yet sure how best to deal with it.

What’s wrong with those stress-reduction behaviors listed first? Why not watch television or get a lot of sleep when you’re feeling stressed, if that makes you feel better? While it may feel better temporarily to escape feelings of stress in those ways, ultimately they may cause more stress themselves. If you’re worried about grades and being too busy to study as much as you need to, then letting an hour or two slip by watching television will make you even more worried later because then you have even less time. Eating too much may make you sluggish and less able to focus, and if you’re trying to lose weight, you’ll now feel just that much more stressed by what you’ve done. Alcohol, caffeine, smoking, and drugs all generally increase one’s stress over time. Complaining to friends? Over time, your friends will tire of hearing it or tire of arguing with you because a complaining person isn’t much fun to be around. So eventually you may find yourself even more alone and stressed.

Yet there is a bright side: there are lots of very positive ways to cope with stress that will also improve your health, make it easier to concentrate on your studies, and make you a happier person overall.

Coping with Stress

Look back at your list of stressors that you circled earlier. For each, consider whether it is external (like bad job hours or not having enough money) or internal, originating in your attitudes and thoughts. Mark each item with an E (external) or an I (internal).

You may be able to eliminate many external stressors. Talk to your boss about changing your work hours. If you have money problems, work on a budget you can live with (see Chapter 11 "Taking Control of Your Finances"), look for a new job, or reduce your expenses by finding a cheaper apartment, selling your car, and using public transportation.

What about other external stressors? Taking so many classes that you don’t have the time to study for all of them? Keep working on your time management skills (Chapter 2 "Staying Motivated, Organized, and On Track"). Schedule your days carefully and stick to the schedule. Take fewer classes next term if necessary. What else can you do to eliminate external stressors? Change apartments, get a new roommate, find better child care—consider all your options. And don’t hesitate to talk things over with a college counselor, who may offer other solutions.

Internal stressors, however, are often not easily resolved. We can’t make all stressors go away, but we can learn how to cope so that we don’t feel so stressed out most of the time. We can take control of our lives. We can find healthy coping strategies.

All the topics in this chapter involve stress one way or another. Many of the healthy habits that contribute to our wellness and happiness also reduce stress and minimize its effects.

Get Some Exercise

Exercise, especially aerobic exercise, is a great way to help reduce stress. Exercise increases the production of certain hormones, which leads to a better mood and helps counter depression and anxiety. Exercise helps you feel more energetic and focused so that you are more productive in your work and studies and thus less likely to feel stressed. Regular exercise also helps you sleep better, which further reduces stress.

Get More Sleep

When sleep deprived, you feel more stress and are less able to concentrate on your work or studies. Many people drink more coffee or other caffeinated beverages when feeling sleepy, and caffeine contributes further to stress-related emotions such as anxiety and nervousness.

Manage Your Money

Worrying about money is one of the leading causes of stress. Try the financial management skills in Chapter 11 "Taking Control of Your Finances" to reduce this stress.

Adjust Your Attitude

You know the saying about the optimist who sees the glass as half full and the pessimist who sees the same glass as half empty. Guess which one feels more stress?

Much of the stress you feel may be rooted in your attitudes toward school, your work—your whole life. If you don’t feel good about these things, how do you change? To begin with, you really need to think about yourself. What makes you happy? Are you expecting your college career to be perfect and always exciting, with never a dull class or reading assignment? Or can you be happy that you are in fact succeeding in college and foresee a great life and career ahead?

Maybe you just need to take a fun elective course to balance that “serious” course that you’re not enjoying so much. Maybe you just need to play an intramural sport to feel as good as you did playing in high school. Maybe you just need to take a brisk walk every morning to feel more alert and stimulated. Maybe listening to some great music on the way to work will brighten your day. Maybe calling up a friend to study together for that big test will make studying more fun.

No one answer works for everyone—you have to look at your life, be honest with yourself about what affects your daily attitude, and then look for ways to make changes. The good news is that although old negative habits can be hard to break, once you’ve turned positive changes into new habits, they will last into a brighter future.

Learn a Relaxation Technique

Different relaxation techniques can be used to help minimize stress. Following are a few tried-and-tested ways to relax when stress seems overwhelming. You can learn most of these through books, online exercises, CDs or MP3s, and DVDs available at your library or student health center. Practicing one of them can have dramatic effects.

- Deep breathing. Sit in a comfortable position with your back straight. Breathe in slowly and deeply through your nose, filling your lungs completely. Exhale slowly and smoothly through your mouth. Concentrate on your breathing and feel your chest expanding and relaxing. After five to ten minutes, you will feel more relaxed and focused.

- Progressive muscle relaxation. With this technique, you slowly tense and then relax the body’s major muscle groups. The sensations and mental concentration produce a calming state.

- Meditation. Taking many forms, meditation may involve focusing on your breathing, a specific visual image, or a certain thought, while clearing the mind of negative energy. Many podcasts are available to help you find a form of meditation that works best for you.

- Yoga or tai chi. Yoga, tai chi, and other exercises that focus on body position and slow, gradual movements are popular techniques for relaxation and stress reduction. You can learn these techniques through a class or from a DVD.

- Music and relaxation CDs and MP3s. Many different relaxation techniques have been developed for audio training. Simply play the recording and relax as you are guided through the techniques.

- Massage. Regular massages are a way to relax both body and mind. If you can’t afford a weekly massage but enjoy its effects, a local massage therapy school may offer more affordable massage from students and beginning practitioners.

Get Counseling

If stress is seriously disrupting your studies or your life regardless of what you do to try to reduce it, you may need help. There’s no shame in admitting that you need help, and college counselors and health professionals are there to help.

Tips for Success: Stress

- Pay attention to, rather than ignore, things that cause you stress and change what you can.

- Accept what you can’t change and resolve to make new habits that will help you cope.

- Get regular exercise and enough sleep.

- Evaluate your priorities, work on managing your time, and schedule restful activities in your daily life. Students who feel in control of their lives report feeling much less stress than those who feel that circumstances control them.

- Slow down and focus on one thing at a time—don’t check for e-mail or text messages every few minutes! Know when to say no to distractions.

- Break old habits involving caffeine, alcohol, and other substances.

- Remember your long-range goals and don’t obsess over short-term difficulties.

- Make time to enjoy being with friends.

- Explore new activities and hobbies that you enjoy.

- Find a relaxation technique that works for you and practice regularly.

- Get help if you’re having a hard time coping with emotional stress.

Journal Entry

All college students feel some stress. The amount of stress you feel depends on many factors, including your sleeping habits, your exercise and activity levels, your use of substances, your time management and study skills, your attitude, and other factors. As you look at your present life and how much stress you may be feeling, what short-term changes can you start making in the next week or two to feel less stressed and more in control? By the end of the semester or term, how would you ideally like your life to be different—and how can you best accomplish that? Write your thoughts here.

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

Key Takeaways

- Everyone feels stress, and many of the things that cause stress won’t go away regardless of what we do. But we can examine our lives, figure out what causes most of our stress, and learn to do something about it.

- Stress leads to a lot of different unhealthy responses that actually increase our stress over the long term. But once we understand how stress affects us, we can begin to take steps to cope in healthier ways.

Checkpoint Exercises

-

Why should it not be your goal to try to eliminate stress from your life completely?

__________________________________________________________________

-

List three or more unhealthful effects of stress.

__________________________________________________________________

-

Name at least two common external stressors you may be able to eliminate from your life.

__________________________________________________________________

-

Name at least two common internal stressors you may feel that you need to learn to cope with because you can’t eliminate them.

__________________________________________________________________

-

List at least three ways you can minimize the stress you feel.

__________________________________________________________________