Response to Stimuli

Invertebrate Response to Stimuli

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lab activity, students will be able to:

- Properly handle live organisms

- Design and carry out a study/experiment that is relevant to the biology of the organism

- Formulate valid and logical questions, hypotheses, and predictions

- Conduct a library and internet search for information on the biology of the organism

- Create data collection tables

- Reliably collect qualitative and quantitative data

- Determine and carry out an analysis plan that is appropriate for the data collected and the question

- Interpret data considering background information

- Communicate the study on a scientific poster at the Augustana Student Academic Conference

1. Lab Overview and Background

Throughout the semester, you have been learning and practicing various lab skills that are important for your development in biology. One of the key skills that has been practiced is working with the scientific process. In this lab activity, you will be putting your scientific process and observational skills to the test by designing and carrying out a team project that investigates the general topic of how organisms respond to stimulus.

Being able to respond to environmental conditions is essential to the survival of all organisms. Measuring how organisms respond can be an exciting and challenging experience. There are 2 options for measuring the response to stimuli: behavioral or physiological, using methods introduced in the pill-bug variation lab. Both measures can provide insights into how populations will respond to future changes (i.e., climate change, acid rain, light pollution).

You will be working in a team to design and carry out an experiment that tests an invertebrate species’ response to biologically relevant stimuli. To do this, you will be researching the natural history of your organism, identifying relevant stimuli, and using the provided materials to design a test arena and manipulate a variable to determine how the organism responds. Finally, you will be presenting your experimental results in a scientific poster presentation at the Student Academic Conference.

1.1 Types of Stimuli

Organisms are constantly receiving information from their environment through receptors (e.g., photoreceptors, chemoreceptors) which allows them to adjust to stay within their optimal conditions. This is advantageous because the environment changes regularly (e.g., circadian, resources, humidity, temperature), and keeping within optimal conditions allows for lower energy expenditure, resulting in overall greater survival and reproductive success. Whether or not an organism will respond to the environmental changes (i.e., stimuli) will depend on their natural history and current physiological state. Through natural selection, certain stimuli will consistently elicit a response, which would make it an adaptive responses (e.g., conglobation in Armadillidium vulgare in response to low humidity; (Smigel and Gibbs 2008)[1]). There are a number of stimuli that can be relevant to organisms, depending on their natural history:

- Temperature (e.g., hot to cold gradient)

- Light (e.g., brightness, colour)

- Chemical (e.g., food, conspecific, substrate pH, scent)

- Gravity (e.g., slope)

- Moisture (e.g., substrate moisture, environmental humidity)

- Touch/pressure (e.g., type of substrate, vibrations)

Whenever we are testing the response of an organism to different stimuli, it is important to think about the adaptive advantage of responding (i.e., why would they respond) and ensuring that we do not cause harm to the organisms (e.g., if the natural range of temperature for an organism is 15-25°C, then we would test slightly outside of the range [10-30°C]).

1.2 An introduction to measuring behaviour[2]

Within each sub-discipline of biology there are different sampling methods and techniques that are employed. For this part of the activity, we are working in the sub-discipline of animal behaviour. To reliably collect behavioural data, there are a few aspects of measuring behaviour that need to be understood:

A) Ad libitum observations

Before research questions are formulated, it is essential to become familiar with your test subject. You can do this by watching the test subject closely and recording everything you observe (e.g., how does the subject move? Does it interact with other individuals or aspects of its environment?). In behavioural studies, we call this ad libitum observations (=opportunistic and free-form narrative). During your ad libitum observations, you should simply describe what you see, not attribute a function or purpose of the behaviour. Be descriptive in your observations to assist with operational definitions. You will carry out ad libitum observations as part of your preparatory activities.

B) How do you collect behavioural data reliably?

Reliability is concerned with how repeatable (i.e., precise) and consistent measurements are. One way we do this is by creating a list of behaviours with operational definitions, which is the complete description of each behaviour. Keep in mind that any observer should be able to score behaviours in the same way, so you need to be as specific as possible. For example, if the behaviour is a tail wag, what would constitute one tail wag? Describe this explicitly.

C) How do we sample behaviour?

There are 2 general types of observational methods that can be employed when observing animal behaviour: continuous and instantaneous sampling. The sampling method you employ will depend on who (individual vs. group) you are observing and what variables you are measuring. It is important that you maintain the same sampling method across test subjects to ensure consistency.

- Continuous sampling (e.g., video recording) – recording all incidences of behaviour for one individual for a set amount of time. You will only be able to focus on one individual for the duration of the sampling period, which means that you must be able to identify the same individual over the sampling period.

- Instantaneous/scan sampling (e.g., photo) – In this type of sampling, the observer takes a scan of what each individual is doing within the test arena at specified times, such as every 30 seconds. Here you are not concerned about who is involved, just that the behaviour is occurring. You can collect data on one or multiple individuals.

D) Behavioural Variables

One of the challenging aspects of behavioural studies is knowing what you should be measuring, and ensuring that the measurements are as objective as possible (i.e., would a second observer score the behaviour the same). There are 4 main variables that can be measured:

- Duration – This variable can be presented in numerous ways, for example: 1) the length of time that one occurrence of a specific behaviour occurs (e.g., the gerbil drank for 30 seconds), 2) the total duration of all incidences of a specific behaviour, within a specified time frame (e.g., the gerbil drank for a total of 2 minutes within the 10 minute observation period), 3) proportion/percent of the observation period during which the behaviour occurred (e.g., the gerbil drank for 20% of the total observation period), 4) the mean duration of a single occurrence of the specified behaviour (e.g., the gerbil had 5 bouts of drinking, with the average drinking bout length being 20 seconds)

- Latency – time from stimulus event to the first observable behaviour (e.g., how long it takes for an amoeba to start moving after light shock)

- Frequency – the number of times a specific behaviour occurs per unit time (i.e., rate), or the total number times the behaviour occurs. If the latter, you must indicate within what time frame. (e.g., the cat flicked its tail at a rate of 30 flicks/min or the cat flicked its tail a total of 300 times within 10 minutes).

- Intensity – looks at the strength of the response. If done quantitatively, intensity can be meaningful. For example, if a dog is presented with a loud noise we could look at how many strides the dog took within a time frame (i.e., speed), how far the dog retreats, the weight of food a dog consumes within one day following the loud noise. Intensity can also be measured as choice between conditions. For example, if a group of pillbugs is presented with humid or dry conditions, we can measure the intensity of choice by counting how many individuals are present in each environment every minute for 10 minutes.

1.3 Measuring Physiological Response

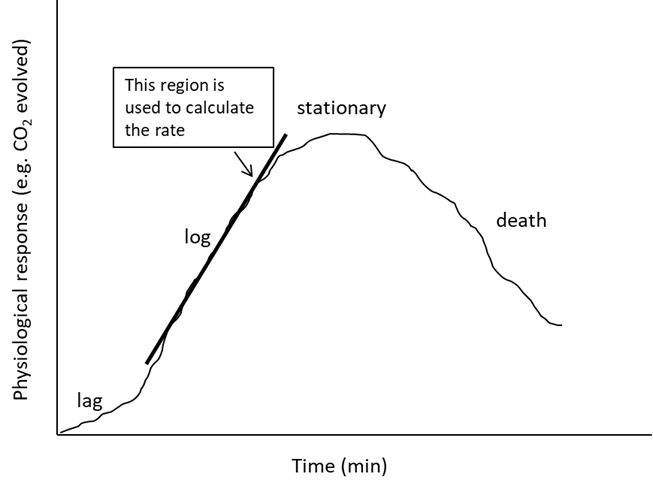

We can use CO2 production to generate a physical response curve. A physical response curve simply represents how a system (i.e., organism) responds to a specific stimulus (i.e., condition). We can use the physical response curve to determine how varying a specific stimulus affects our test system. When we look at the physical response curve in Figure 1, we can see that the rate of reaction differs over time (i.e., the slope of the line varies at different points in time). This means that to make a meaningful comparison between conditions, we need to extract information from the physical response curve. Within most systems, there will be a lag phase (time for the reaction to begin), the log phase (reaction occurs at a maximum rate) and a stationary phase (rate of reaction plateaus often due to accumulation of end products or lack of reactants). In some situations, we may see a death phase (quantity of dependent variable produced is outnumbered by quantity consumed or degraded). We should NOT see a death phase in our systems because the organisms should not be placed in a situation that stressful.

Figure 1. Physical response curve components. The curve shows a lag phase (time for the reactions to begin), a log phase (reactions occur at a maximum rate), stationary phase (rate of reaction plateaus – often due to accumulation of end products or lack of substrates), and a death phase (the quantity of dependent variable produced is outnumbered by a quantity consumed or degraded. This phase only applies to physiological growth curves).

Variables:

- Time – how long is the log or lag phase (i.e., duration), how quickly is the plateau (stationary phase) reached

- Physiological (should be converted to mass specific by dividing by mass) – Total mass specific CO2 produced (ppm/g), rate of mass specific CO2 production at different times (slope of the line), maximum rate of mass specific CO2 production (slope of the line during log phase)

1.4 Tips for Successful Teamwork

It is always useful to have a role for each person within your team. Given how you have worked together in the past and what you each want to learn, think about who is best for each role:

- In-lab Manager – this person makes sure everyone has a job to do (including themselves), keeps track of what has been done and what is left to do.

- Team Facilitator – this is the person who will organize the meetings, keeps track of what has been done (in terms of the assignment) and what is left to do.

- Recorder – this person takes notes during team meetings, writes out the decided upon task list (and shares with everyone; e.g.., who makes the figure) and sends out the reminder emails regarding deadlines (if needed).

- Editor – this person takes the last read through the assignment before handing it in. The person that is best in this case is one who knows formatting information and has good grammar/spelling. Note: The editor should not submit an assignment with large changes without first passing the edits by the team.

Note: Make sure you have contact information for each team member! There will be substantial work to do outside of lab time.

- Smigel JR, Gibbs AG. 2008. Conglobation in the pill bug, Armadillidium vulgare, as a water conservation mechanism. J Insect Sci. [accessed 2023 Dec 22]; 8(44): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1673/031.008.4401. ↵

- Source Consulted: Martin P, Bateson P. 1986. Measuring Behaviour: an introductory guide. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press. ↵