Fern gametophytes in varying densities

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lab, you should be able to:

- Use aseptic technique to inoculate plates with fern spores

- Use a serial dilution technique to sequentially alter spore density

- Carry out basic sampling and observations using both dissecting and compound microscopes

- Make detailed observations using a microscope

- Make properly formatted scientific drawing

- Summarize and present data in a meaningful way

- Communicate findings in an appropriate format for the biological sciences

1. Lab Overview and Background

In the lab, we will be manipulating the number of Ceratopteris richardii spores sown. After 2-3 weeks of growth and development, we will quantify the number of male and hermaphrodite gametophytes found in each density. There are 2 questions that we are addressing: 1) does gametophyte density influence sex expression in C. richardii? and 2) does gametophyte density influence hermaphroditic gametophyte size?

1.1 Fern Life Cycle and Model Organism

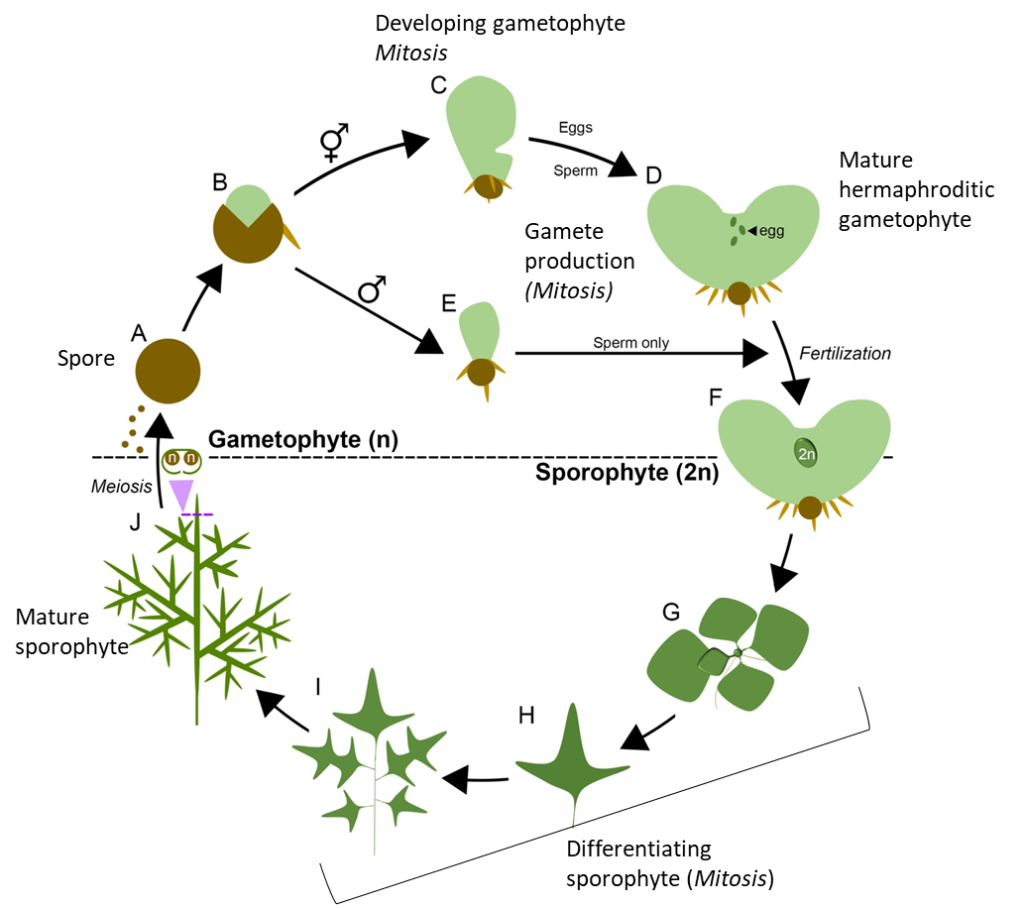

Ferns, like all plants, have a different life cycle compared to other organisms. One of the major differences is that both the haploid and diploid portions of the life cycle are multicellular (alternation of generations; Figure 1). The organism we are using in this lab is Ceratopteris richardii, a fern found in tropical, semi-aquatic environments. The C. richardii strain we are using has been specifically bred to complete its life cycle in a short period of time and can successfully be grown in a greenhouse or lab under warm, humid conditions.

The following are highlights of the Ceratopteris richardii life cycle: (capital letters correspond to the letters on Figure 1):

- Single-celled, haploid spores (A) are produced by meiosis (J), germinate (B) and develop (through mitosis) into multicellular gametophytes (C [hermaphroditic] & E [male]).

- Mature, multicellular haploid gametophytes produce gametes by mitosis (D). The mature haploid gametophytes consisting of a small thallus with rhizoids, vegetative cells, and sexual organs, known as antheridia (which produce sperm; both male and hermaphroditic gametophytes) and archegonia (which produce eggs; hermaphroditic gametophyte).

- When in a moist environment, sperm are released from the antheridia and the archegonium neck opens to release a chemical that attracts sperm to swarm at the neck of the opening. The sperm swim down the neck and fertilize the egg.

- Fertilization of gametes results in a diploid zyzgote, which develops within the archegonium (female sex organs) on hermpahroditic gametophytes (F).

- The zygote further grows through mitotic cell division and differentiates (G-I) by mitosis to form the sporophyte (dominant generation). The mature sporophyte has leaves, stems, and roots with vascular tissue.

- The gametophyte develops and matures independently from the sporophyte (not found within gymnosperms or angiosperms).

Figure 1. Life cycle of Ceratopteris richardii. (Source: Plackett et al. 2018 under CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED; labels added by J. Rintoul).

1.2 The growing gametophyte – development and sex differentiation

The pattern of gametophyte growth is predictable, 2-dimensional pattern from two cells, but there are conditions that can influence the rate of growth and overall morphology (e.g., “stretched” gametophyte, “tongue-shaped” gametophyte), such as light intensity and quality, photoperiod, nutrients (e.g., Racusen 2002) and population density (e.g., Huang et al. 2004). For example, in high density environments, Huang et al. (2004) found that the frequency of male gametophytes increased as density increased. They also found that gametophyte area (length x width) decreased significantly as density increased, most likely due to resource competition.

Ceratopteris richardii is considered to be homosporous (i.e., have one kind of spore developed in the sporangia), however, 2 types of gametophytes can develop:

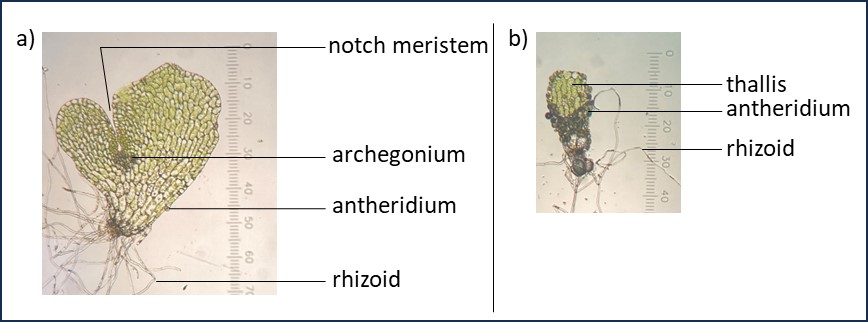

- Hermaphroditic gametophytes (Figure 2a), which have both archegonia and antheridia. These gametophytes have indeterminate growth within the defined meristematic region (notch meristem), which stops once an egg is fertilized within the archegonium.

- Male gametophytes (Figure 2b), which produce a large number of antheridia antheridia. These gametophytes have determinate growth resulting in a smaller, tongue-shaped gametophyte that lacks a meristematic region.

Figure 2. Mature Ceratopteris richardii a) hermaphroditic, and b) male gametophytes. Photos taken through Kyowa microscope at 100x total magnification (calibration: 1 ocular unit = 10 μm).

Sex differentiation in C. richardii is dependent on antheridiogen (ACE), a pheromone produced by hermaphroditic gametophytes late in the stages of development (i.e., once the notch meristem is developed; Atallah and Banks (2015)). If ACE is present, it leads to development of male gametophytes. Once the meristem is developed, the gametophyte is no longer sensitive to ACE. Therefore, in a population of spores where there is variation in spore germination timing:

- the first spores to develop will be hermaphrodites since there is no ACE present in the environment early in their development.

- all subsequent spores developing in close proximity to the hermaphrodites will become male gametophytes since there is ACE present early in their development.

References

Atallah NM, Banks JA. 2015. Reproduction and the pheromonal regulation of sex type in fern gametophytes. Front Plant Sci. 6: 1-6.

Huang Y-M, Chou H-M, Chiou W-L. 2004. Density affects gametophyte growth and sexual expression of Osmunda cinnamomea (Osmundaceae: Pteridophyta). Annals of Botany. 94: 229-232.

Plackett ARG, Conway SJ, Hewett Hazelton KD, Rabbinowitsch EH, Langdale JA, Di StilioVS. 2018. LEAFY maintains apical stem cell activity during shoot development in the fern Ceratopteris richardii. eLife 7:e39625. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.39625.006.

Racusen RH. 2002. Early development in fern gametophytes: interpreting the transition to prothallial architecture in terms of coordinated photosynthate production and osmotic ion uptake. Annals of Botany. 89: 227-240.

- Adapted from: Hickok L, Warne TR. 2006. C-fern manual. Burlington (NC): Carolina Biological Supply Company. ↵