6 Chapter 6: The Razor’s Edge: How to Balance Risk in Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Big Data

Joel Templeman

The path to Salvation is as narrow and as difficult to walk as a razor’s edge.

― W. Somerset Maugham

This chapter is guided by the question, how can an educational system take advantage of rapid technological advances in a safe and socially responsible manner while still achieving its mandate of fostering and supporting learner success? Artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML) , and big data are examples of highly risky technologies that also hold vast potential for innovation (Floridi et al., 2018). In examining technological advances from an ethical perspective, one of the aims is to avoid harm and minimize risk. This is referred to as a consequentialist perspective (Farrow, 2016). The complexity of finding and maintaining a proper balance in advancing technological innovation and avoiding harm and minimizing risk cannot be understated. This quest for an educational “sweet spot” is mired by a lack of understanding, inconsistent leadership, and simple human greed.

Educators are inundated with information and change on a daily basis, and this accelerated greatly in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and related health restrictions. Technologies such as AI, ML, and big data may be outside an educator’s expertise or interest; however, they have the potential to impact teaching practice and students’ lives in significant ways. Teachers are often required to rely on experts and popular media to guide their learning about emerging technologies or to inform decision-making. At times, even when teachers have an informed opinion, they lack the organizational authority to make certain decisions regarding changes needed in the learning environment. One such area in which teachers may feel limited in their choices is the rapidly evolving infiltration of educational technology (EdTech) in the classroom, and specifically the automation within EdTech that exploits the capabilities of technologies (e.g., AI, ML, and big data) that augment functions historically in the domain of the teacher. This chapter is about how humans’ carbon intelligence (biological) will begin to coexist with computers’ silicon intelligence (machine; Shah, 2016) in learning, without the formal educational system acting as a gatekeeper of personal privacy, from a consequentialist perspective (Farrow, 2016).

Discussion about the appropriate use of advanced technologies is not limited to the classroom, as this integration impacts all aspects of living in a digital age. For everyone with access to technology, their experience will be shaped by systems and their interactions with those systems. In an educational context, learners are subjected to information technology (IT) platforms at all levels, and these interactions require the system to “know” things about the users. For these systems to be accepted and to benefit the users and the education system, without abuse or discrimination, certain ethical norms must be established and maintained. In the past, this trust relationship was between teacher and student, but now the role of teacher is being increasingly augmented by computer networks. Many educators are not comfortable turning over any of their traditional tasks to systems that they neither fully control nor fully understand. To further burden the relationship between teachers and IT systems is the proliferation of abuses (e.g., monitoring student behaviour to target them with advertising) and misuses of personal information (e.g., applying tools to areas in which they are not proficient or appropriate, such as use of algorithms trained to identify successful applicants to higher education programs based on existing patterns) by companies and bad actors who develop and maintain these systems. Although these problems are a subset of all the applications, the impact on individuals is nonetheless a clear and present danger.

This chapter is not about the efficacy of using automation to create autonomous learning machines or computer-assisted instruction. Justin Reich (2020) detailed in his book Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education why attempts to utilize machines to replace teachers continue to fail at scale. Instead, the focus of this chapter is on IT systems used for the simple management of content and as facilitator of communication and collaboration between educators and learners at all levels (McRae, 2013). The analysis in this chapter requires imagining what could be and not necessarily a description of what is. I argue that change is essential for institutions to remain relevant and that individuals within the organization need to find ways to adapt to new paradigms while remaining protected from harms.

Section 1: Full Disclosure: Why Do Haters Hate?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is generally understood to involve computers performing tasks that are normally carried out by humans (e.g., speech recognition, facial recognition, language translation). There is a valid argument to be made for positive AI applications in the world. In the podcast “From Sea to Sky” from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (Noorani, 2019), Andrew Blum, author of The Weather Machine: A Journey Inside the Forecast, highlighted that great advances in weather forecasting are possible because of the utilization of and advances in AI. Prediction quality is gaining roughly “a day a decade,” so that a 5-day forecast is now about as good as a 4-day forecast was a decade ago, and a 2-day forecast was 30 years ago. AI uses computing power and huge collections of data to help answer challenging questions about trends and patterns in weather systems (Fremont, 2018). This example shows tech utilization for the common good.

When computers learn and adapt using algorithms and statistical models, this is generally referred to as machine learning (ML), and when the data sets become extremely large they are referred to as big data. The accumulation of massive databases of information is a prerequisite for the implementation of AI and ML. All of this data and metadata are used to make sense of what the user is doing (as part of a quest to accurately predict what the user is thinking and ultimately foresee future user behavior). The number of collected data points are multiplying. The number of connected devices—what’s also called the Internet of Things (IoT) —with the ability to collect and share information is also growing exponentially. “The quality and scope of the data across the Internet of Things generates an opportunity for much more contextualised and responsive interactions with devices to create a potential for change,” said Caroline Gorski, the head of IoT at Digital Catapult, in a Wired article (Burgess, 2018). Although data collection is on the rise, the majority of existing data remains unusable and is referred to as dark data (e.g., data archives, repositories, computer system logs) to indicate the inability to use it for anything meaningful at this time (Reiley, 2019).

One significant factor leading to distrust of technological systems is the lack of consequences for inappropriate or unlawful acts (Regan & Jesse, 2019). In cases where there is manipulation and misuse of the rules, there must be accountability and justice. Where innovation disrupts processes and protections, adjustments need to be made to realign systems. For example, simply meeting the minimum legal requirements (based on user agreements) is not sufficient to protect minors from harm and risk (Floridi et al., 2018). Increasing regulatory minimums does not serve to achieve the desired results either.

There are legitimate reasons to be concerned when it comes to use of advanced technology such as AI, ML, and big data in education. Computational power coupled with massive amounts of available data is a high-risk combination. There is a potential for abuse and misuse. From an ethical point of view, the question often asked is, just because we can, should we? How can these technologies be managed to avoid harm and minimize risk?

Section 2: Privacy/Informed Consent

Privacy is the idea that some things must be held as secret. A secret, by definition is something not known or seen or not meant to be known or seen by others. “Secrecy is the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups who do not have the “‘need to know'” (“Secrecy,” 2021, para. 1), while still sharing it with other individuals who are deemed by the secret’s owner to be permitted to know. That which is kept hidden is known as the secret.

In the context of this chapter and EdTech in general, the collection of the information and even the insight brought about by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is not seen as the problem if the information is in the “right hands” (as determined by the secret’s owner) and for legitimate purposes (as agreed to by the owner and the authorized recipient). Those who see and reuse these secrets for their own benefit while returning little or nothing to the individual user are considered the problem. So the issue isn’t the information, or the secret, but who holds the secret and to what end that information is employed.

Count not him among your friends who will retail your privacies to the world.

The general term “privacy” is better clarified by identifying six specific ethical areas of concern: information privacy, anonymity, surveillance, autonomy, discrimination, and copyright (Regan & Jesse, 2019). The discussion about privacy, with all of its nuances, is made more complex in that everyone has a personal definition of and relationship with privacy, which is informed by their personal experience and place in history.

David Vincent, author of Privacy: A Short History, discussed on a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation podcast (Noorani, 2021) how the Eurocentric concept of privacy has changed over time and how relatively recent the idea of individualism is. This new concept of all individuals owning and managing secrets or intellectual property requires a culture to develop around it and laws and social morays to support it. However, while individuals are desiring ever-increasing levels of anonymity, corporations are putting into place systems designed to achieve the exact opposite. Individual sovereignty doesn’t exist in technology. The use of one-time user agreement forms, sometimes called “click-wrap” or “browse-wrap,” where a company is indemnified when a user clicks “OK,” or even just through the user’s presence on the webpage (Zuboff & Schwandt, 2019), is an act of an individual relenting, not consenting. The user, even if they have read and fully understood the agreement, gives carte blanche approval for any and all data uses, including future unknown uses of the data exposed through repurposing, reselling, or unintended breach. This is a concern in education when the institution adopts a management system that the participants, teachers, and students are required to utilize, but data ownership falls to the corporation or is otherwise negotiated between the educational institution and the company. Too often though, this relationship is unknown or unclear to the educational institutions and the users. The commodification of student data by allowing the direct and unrestricted access of private corporations into the education environment requires greater community involvement (Reich, 2020).

Some promising innovations, such as edge computing, may allow for closed institutions to take advantage of the computing power found in the cloud while retaining ownership and control over sensitive internal data. However, without a new funding model, the costs involved in developing and maintaining a not-for-profit infrastructure for education to rival the might of multi-billion-dollar corporations make this option unrealistic. Global giants can be less constrained by social responsibility and operate without regulations given their focus on profit from their commercial innovations.

End users are not workers, not products, and not customers. End users are the source of raw material in the form of data. Every kind of online transaction results in by-products, referred to as data exhaust (Zuboff & Schwandt, 2019). Analysis of this dark data, when aggregated on a massive scale, reveals patterns of human behaviour. Patterns are the gateway to predictability and the collection of this information can be used in ways that are not yet understood (Regan & Jesse, 2019) with fears of abuse and misuse (Floridi et al., 2018). The keepers of power in the past were giants of manufacturing; now, the richest and most powerful are those that control technology, including Google, Facebook, Amazon, Tesla, Alibaba, Baidu, and more.

The antidote to current worries regarding AI in education, and AI in general, is to evoke democratic and legal processes available to the people and hold actors accountable for actions counter to the common good. This will require users to become informed and take appropriate actions (Cadwalladr, 2020).

Section 3: Avoiding Harm and Minimizing Risk

Risk is a quotient of the unknown events to come. Risk is not, in and of itself, negative, because it represents an assessment of both the danger and opportunity of possible future events. Risk assessments are already heavily employed by IT system managers to address physical and IT security risks such as fires, floods, and hackers in the protection of equipment and data, but these rarely get used by those who manage the software and users who utilize the software to complete their work. Educators, supported by IT specialists, can identify every piece of software they use and provide a risk assessment from the user point of view. Issues to consider are secure data collection, transmission, processing, and storage; use of tracking tokens (cookies); the credibility and reliability software vendors and subcontractors; location of servers (jurisdiction); value of user data; value of user identity; user autonomy; and more. The list is as long and detailed as is appropriate for the organization to determine where and what safeguards are required to reduce risks to an acceptable level.

Ethical use of technology, avoidance of doing harm to others, and minimization of risk are key components of a strategy to embrace innovation in learning. There are significant risks to employing powerful and rapidly developing technologies, but work is already underway to establish new norms and protections, rewrite laws, and develop new ways of thinking. Since these risks are widespread and interrelated, it is important to first develop maps and frameworks so that work can occur simultaneously in all areas without delay, while benefiting as much as possible from coordination and collaboration with other actors. Legal and moral frameworks can help manage misuse and unintentional mishaps, but dedication and discipline are required to resist corruption of these systems. For inspiration from other areas where risky innovation is embraced and successfully integrated, we can look to healthcare, for example (see Dunham, this volume).

The move toward technological transformation in institutions has made devices and connectivity ubiquitous. Although this change has concurrently isolated and further disadvantaged those who live in remote, rural, and low-income communities, the path for the haves is decisively digital. This arch of utilization and adoption has no foreseeable endpoint, so there are calls for proactive adaptation at the pace of risk tolerance for a given organization. It should be noted that this work to assess and mitigate risk must succeed in parallel to efforts to mitigate inequity driven by its many factors.

Section 4: Participant Autonomy and Independence

Despite the risks inherent in artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and big data, each educator can find ways to contribute to the ethical use of technology and in particular identify cases where misuse or abuse occurs. Leadership remains responsible for ensuring that appropriate safeguards are established and maintained while fostering a culture of informed participation (Floridi et al, 2019). In cases where policies and best practices do not exist or have not been adopted, creating interim solutions based on best efforts should be established and continually improved upon. Fortunately, much work has already been done and is available to inspire adaptations appropriate to a given situation.

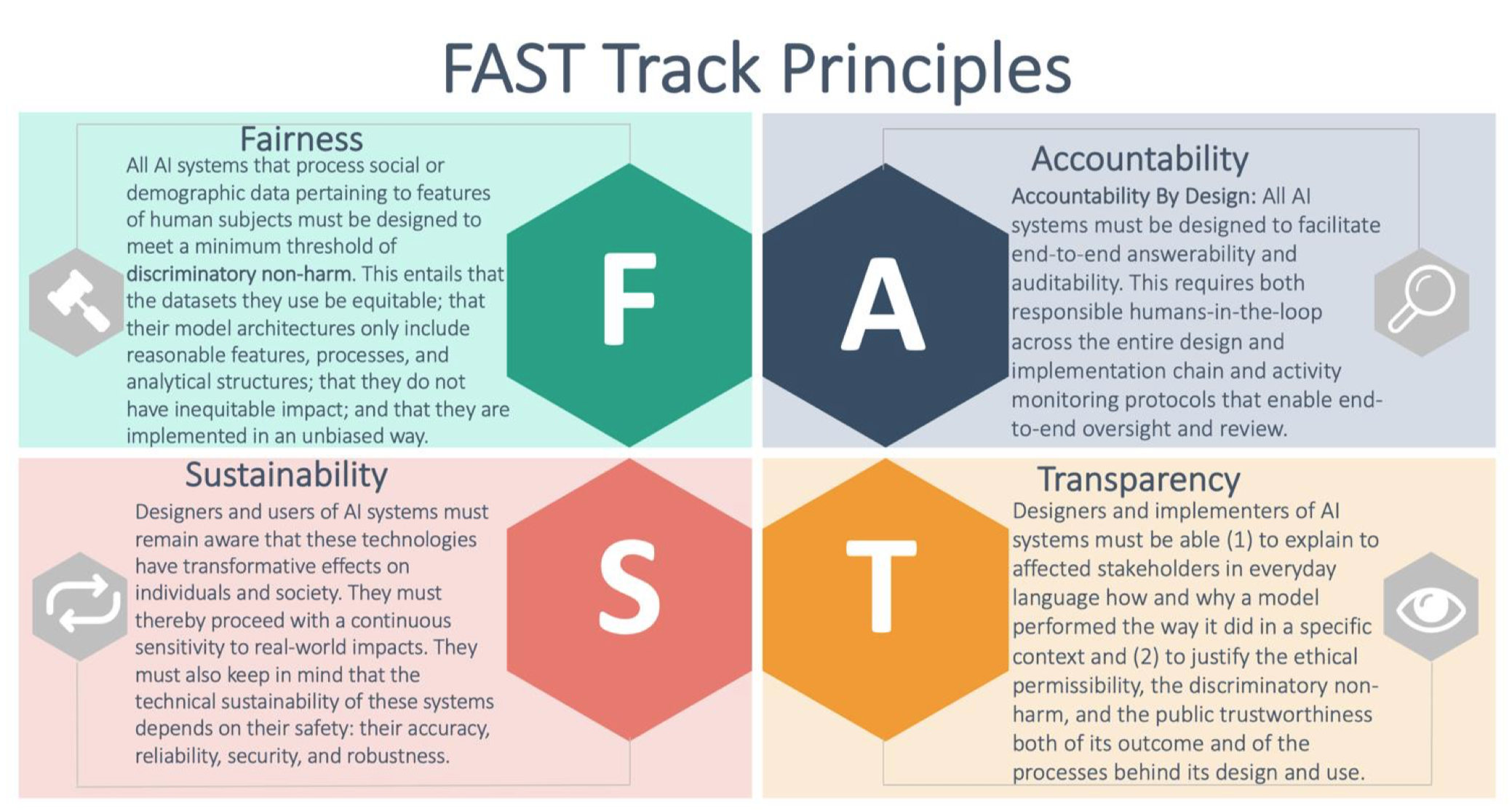

For instance, work by groups such as the Alan Turing Institute, with frameworks like FAST (fairness, accountability, sustainability, and transparency), encourages design teams to consider ethical perspectives in all areas of development (Leslie, 2019). Decision-makers that are employed in educational environments can seek partnerships with companies that declare and follow principles that align with the goals of the institution and act in the best interests of end users to avoid harm and minimize risk. Design teams can follow these basic principles:

In places where a lack of political will or understanding is inhibiting progress, advocacy and coordination of like-minded individuals and groups is critical. Cultural change through strong leadership is required. Change to culture and social norms in any organization is not easy, and each educator will need to determine if they are willing to adapt with the changing environment and, if so, in what ways. All institutions must prepare people for lifelong learning and integration of technology as an enabler of digital literacy. In this day and age, technology lives inside and outside of the classroom and permeates all areas of social and professional realms such that this learning must also occur across all environments.

Adaptation is an ongoing requirement to keep the education system relevant and effective. Floridi et al. (2018) identified four fundamental areas to focus on when thinking about the opportunities and risks of AI with the end goal of human dignity and flourishing (otherwise thought of as the alleviation of suffering; Harari, 2014, 2017). The four areas are as follows:

Working together cohesively is an important condition for adaptive change in education.

In aerospace, humans have defied gravity as an international activity since the earliest days of flight. Even though the technology of flight, nuclear energy, rocketry, and computer systems have been and are still used to control and hurt people and the planet itself, this same knowledge has allowed us to prepare to put humans on Mars, a planet that we didn’t even know existed until 1610. These breakthroughs have been achieved through a process guided by a common mission, collective effort, and formal risk management—critical and fundamental aspects for accomplishing any shared goal. The saying goes: “To go fast, go alone. To go far, go together.” In fact, the ability to conceptualize intangible goals and work collectively toward a common objective is a uniquely human characteristic (Harari, 2014, 2017). Educators have rightly identified the dangers and abuses of educational technology, but if they do not develop a common vision of what is desired, a vision will be imposed by those external to the education community. Likewise, without active participation by educators in building a better solution, one will be provided.

From a pragmatic perspective, it can also be helpful to look at the type of work that is needed to change a system of systems and decide where one is most apt and most interested. At the strategic level, a unified theory of learning with an understanding of the role of technology needs to guide decision-making. If that is too broad of a thought, consider the operational level, which looks at institutional strategies for integrating technology with pedagogy in line with the unified theory of learning (or the best estimation of it available at the time). And, finally, the tactical level is the effective application of technology and systems thinking to curriculum based on institutional strategies and a global vision of best practices.

In practical terms, based on one’s knowledge, interest, capacity, and authority, ensure that the tools that one uses are appropriate and working as planned and as expected. Too often systems are adapted from the initially intended use to complete functions outside of the scope of the original design. Software and hardware are designed with a specific business or use case in mind and with specifications to meet the requirements of that business or use case. Routinely though, business processes change to adapt to external conditions, but business cases are not amended, and so business tools remain the same. These tools are then modified in an ad hoc manner to complete tasks or otherwise function in ways not conceived of by the designers and testers, so gaps form and the potential for unintended consequences grows. This process can fester until conditions and tools become so out of alignment that the system fails, and unintended consequences are realized too late.

Education systems can also benefit from lessons learned in industry regarding system design and risk management to find processes that translate or can be adapted to an academic environment. For most businesses, complex technology integration is on the rise, and digital literacies (including data literacy) are becoming needed competencies and expected employee skills. Teachers and educators will be expected to utilize and manage IT systems, including interconnected and AI-powered applications, so investments in continuous professional learning are needed.

Conclusion

One day, while touring a military parachute packing facility, I was shown an area where specialized rigs were being packed to airdrop all-terrain vehicles and equipment. An impertinent young student paratrooper, possibly in an attempt to be humorous, asked if it was possible to airdrop a main battle tank. Given how massive and heavy a tank is, it seemed likely the answer was going to be no. However, the airborne sergeant replied with a surprisingly astute affirmation paraphrased as follows, “there is a rover rolling around on Mars right now because humans decided to put it there. If the mission required it, we could drop anything into a 10-foot square anywhere on Earth.” His point has resonated with me since that day and has steered my focus toward problem-solving that looks past the technological problems and concentrates on the human factors. What the sergeant was possibly saying in his own way was that human attempts at achieving a particular goal are not really about the technology; they are about the commitment and leadership needed to specify a clear mission and help the specialists find a way to achieve the goal. Applying this logic to artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and big data, the assertion that we can use these technologies in positive and beneficial ways for humanity becomes plausible if we truly want it.

We could change everything in education if we start from a belief in humanity, that under the right conditions we have the capability to have and use technology to positively augment all aspects of human living in a completely fair, economical, accessible, and safe manner. With that core belief, we only need the vision and political will to achieve it. There are processes to deal with the current misuses and abuses of technology and rectify the negative impacts and inequalities that technology is imposing on people, but we must have the courage and strength of character to use them. Technology is made by people and can be controlled and managed by people for the common good—if that is indeed what we choose.

Innovation disrupts existing systems, leading to intended improvements but also unintended problems; however, further innovation can be applied to deal with the negative effects of the first innovation. For example, the supercomputers and data farms required for more and more computing-related activities consume extreme quantities of electrical power and thus contribute to global warming and stress on aging power grids (Bakke, 2017). With further innovation, green power options will replace existing electricity-creating processes that cause harm to the environment, and new technologies will allow the redesign of the existing power grid to ensure constant power is available where and as required. This example highlights the idea that avoiding innovation because it will cause disruption is short sighted.

In education, the argument that educators must resist the use of EdTech because companies are using it as a vector to accumulate a wealth of personal data about the student is problematic because the student is simultaneously pouring their personal information into the same databases through their personal online activities. IoT devices, personal assistants, social media, and wearable devices are siphoning data at such a rate that plugging the hole in EdTech software would amount to an undetectable reduction in personalization. Therefore, the focus must be on eradicating the commodification of humans and the great wealth that can be achieved by those in power by doing so. Ethical and equitable use of technology is possible but is currently being co-opted by greed and lust for power. These are the human factors that first need to be addressed (Swartz, 2000).

How can an educational system take advantage of rapid technological advances in a safe and socially responsible manner while still achieving its mandate of fostering and supporting learner success? Three key areas were highlighted in this chapter from an ethical perspective. To help achieve technological harmony and reap the most benefit, there must be (a) clear and agreed-upon goals; (b) collective and cohesive efforts where individual needs are subservient to the common good; and (c) a methodology to ensure designers, subject-matter experts, and end users work together to meet the needs of all parties equally not just accumulate profit.

Remember that fundamentally, society created the education system, so it can be re-created, redesigned, or dismantled to suit people’s needs. Arguably the role of education is to support society, and our society is one with technology integration, so it follows that learning both in and out of school should be enabled by educational technologies. This has yet to be the case: “Schools, with their innate complexity and conservatism, domesticate new technologies into existing routines rather than being disrupted by new technologies” (Reich, 2020, p. 136). Experiences coming from COVID-19 health restrictions have led to innovative examples where AI, ML, and big data excel and bring value to the teacher and the learner and education systems while also highlighting critical areas where problems must be solved. We each have a role in determining what this future looks like. What is yours?

Questions to consider

- What areas of learning, teaching, and assessment does EdTech currently support appropriately in education?

- How can we maximize and support the use of EdTech in education?

- How can humanity work cohesively to alleviate stress on the areas where EdTech does not work well?

- If the utilization of AI, ML, and big data in education is successful, how will the system be better (more efficient, effective), and what does that mean for the individual (improved life, equity, freedom) and the common good?

References

Bakke, G. (2017). The grid: The fraying wires between Americans and our energy future. Bloomsbury

Burgess , M. (2018). What is the Internet of Things? WIRED explains. Wired. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/internet-of-things-what-is-explained-iot

Cadwalladr , C. (2020, January). Fresh Cambridge Analytica leak ‘shows global manipulation is out of control.’ The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jan/04/cambridge-analytica-data-leak-global-election-manipulation

Farrow, R. (2016). A framework for the ethics of open education. Open Praxis, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.2.291

Floridi, L., & Cowls , J. (2019). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.8cd550d1

Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., Chatila, R., Chazerand, P., Dignum, V., Luetge, C., Madelin, R., Pagallo, U., Rossi, F., Schafer, B., Valcke, P., & Vayena, E. (2018). AI4People—an ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28(4), 689–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-018-9482-5

Fremont, J. (2018). A world without AI is scary. progress Isn’t. Medium. https://medium.com/@hypergiant/a-world-without-ai-is-scary-progress-isnt-4dfd77a1c2ba

Harari, Y. N. (2014). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. Vintage.

Harari, Y. N. (2017). Homo deus: A brief history of tomorrow. Vintage.

Leslie, D. (2019, June 11). Understanding artificial intelligence ethics and safety: A guide for the responsible design and implementation of AI systems in the public sector. The Alan Turing Institute. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3240529

McRae, P. (2013, April 14). Rebirth of the teaching machine through the seduction of data analytics: This time it’s personal. https://philmcrae.com/blog/rebirth-of-the-teaching-maching-through-the-seduction-of-data-analytics-this-time-its-personal1

MIT Comparative Media Studies/Writing. (2020, September 28). Justin Reich, “Failure to disrupt: Why technology alone can’t transform education” [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/aqc4LI1vdO4

Noorani , A. (Executive producer). (September 13, 2019). From sea to sky (No. 446) [Audio podcast]. In Spark. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-55-spark/clip/15736152-446-from-sea-sky

Noorani , A. (Executive producer). (January 29, 2021). The Spark guide to civilization, part five: Privacy (No. 498) [Audio podcast]. In Spark. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.cbc.ca/listen/live-radio/1-55-spark/clip/15821774-498-the-spark-guide-civilization-part-five-privacy

Regan, P. M., & Jesse, J. (2019). Ethical challenges of edtech, big data and personalized learning: Twenty-first century student sorting and tracking. Ethics and Information Technology, 21(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-018-9492-2

Reiley, J. (2019, November 13). A guide to everything you need to know about dark data. Influencive. https://www.influencive.com/a-guide-to-everything-you-need-to-know-about-dark-data/

Reich, J. (2020). Failure to disrupt: Why technology alone can’t transform education. Harvard University Press.

Shah, S. (2016, October 2016). Cognitive ushers us from “carbon intelligence” to AI “silicon intelligence.” Healthcare IT Guy. https://www.healthcareguy.com/2016/10/20/cognitive-carbon-artificial-silicon-intelligence/

Swartz , J., (2000, September 3). ‘Opting in’: A privacy paradox. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/2000/09/03/opting-in-a-privacy-paradox/09385146-74bc-4094-be07-c4322bf87c78/

Secrecy. (2021, October 11). In Wikipedia.

Zuboff, S., & Schwandt, K. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: the fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books.