Conclusion: Teaching #EdTechEthics Course in the Open: An Instructor’s Reflection

Dr. Verena Roberts

Introduction

Developing an awareness of open educational practices (OEP) and a readiness for engaging in open learning, requires an intentional open learning design. Drawing on my dissertation research and scholarship in open education, and my teaching experiences in both post-secondary and K-12 contexts, I believe that in order to teach and learn in the open, the instructor needs to consider a learner’s awareness of and readiness to open learning in general. In this chapter, I will reflect on my experience designing and teaching the #EdTechEthics course in a professional graduate program in education in 2020 and 2021, and the characteristics that describe the process I used to help students develop an awareness of open education and a readiness to engage in OEP. The aim of this chapter is to help other educators interested in integrating OEP into their courses.

As I considered how to use OEP in the #EdTechEthics course, I wanted to ensure that I helped graduate students balance a focus on the learning process and learning outcomes with a clear understanding of the final learning product: a sustainable digital learning artefact. I wanted the students to have opportunities to develop an awareness of the concept of open learning and its potential to influence their engagement in learning experiences that integrate formal and informal learning spaces and affordances. Furthermore, I wanted them to have the time for reflective practice throughout the course in order to consider the potential of open learning in their professional work-place contexts. I aimed to design the learning experience to promote learner agency through co-designing learning activities with the students. The underlying intention of the course design was to support learners in becoming active and knowledge-building participants who contribute to an open learning ecosystem.

Context of the #EdTechEthics Course

As mentioned in the Introduction to this book, the students worked on developing a sustainable digital learning artefact in the format of a book chapter with many layers of support and rounds of feedback. At the beginning of the course, the students were introduced to the project opportunity: to create and co-design one chapter that could be included in a collaborative open pressbook. From the beginning, the students knew they would always have a choice to publish their chapter openly or not. From the Winter 2020 course, 9 students chose to publish their chapters and of the Winter 2021 course, 7 students chose to publish their chapters. All of the students developed their own chapters based on current research and a topic of interest in educational technology and ethics. Students completed this project through multiple stages and check-ins throughout the course. As instructor, my goal was to provide the necessary contextual information and offer a relevant, authentic, and scaffolded learning experience for students (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018). My role was an active participant in the learning process alongside the students. The students also provided a final reflective assignment about their perspectives on the learning process. The students submitted their draft chapter to fulfill course requirements and they were all provided with the option to take an additional step and share their work publicly by participating in the publication of the pressbook. This optional step required additional rounds of editing and revision by the co-editors and a professional copyeditor beyond the duration of the course.

Adapting the OLDI Framework to the Course Context

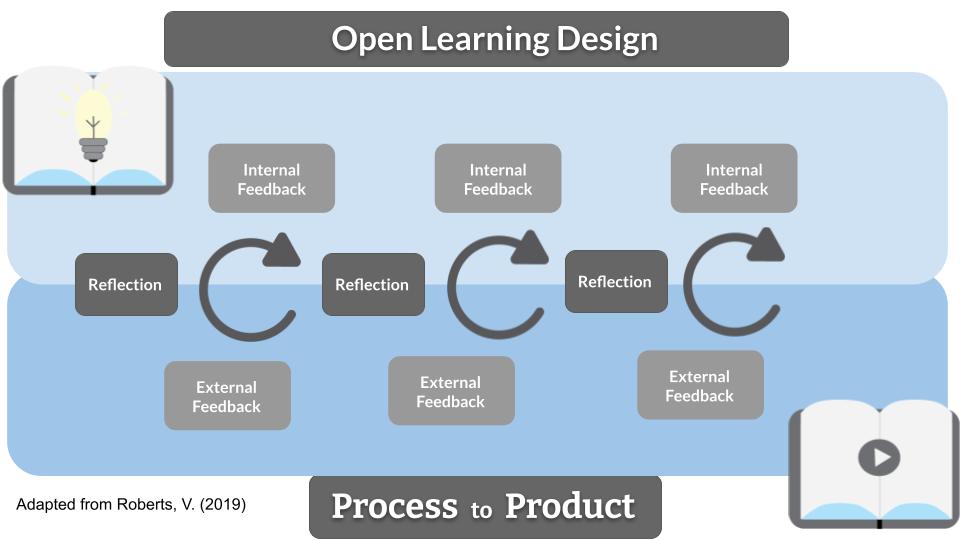

Writing a paper can seem like a typical or classic type of graduate course assignment. Likewise, the structure of an online course with a learning activity of this type can look similar to other online courses focused on content delivery. However, the underlying design features of this course are unique, due to the use of an Open Learning Design Framework (OLDI) (Roberts, 2019). The foundational components of the OLDI framework include the integration of scaffolded and participatory open educational practices, formative assessment strategies, peer feedback loops, and reflection.

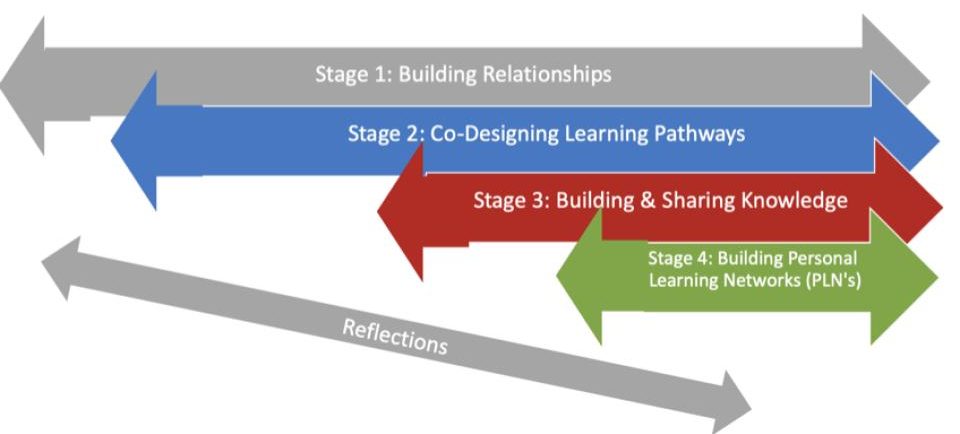

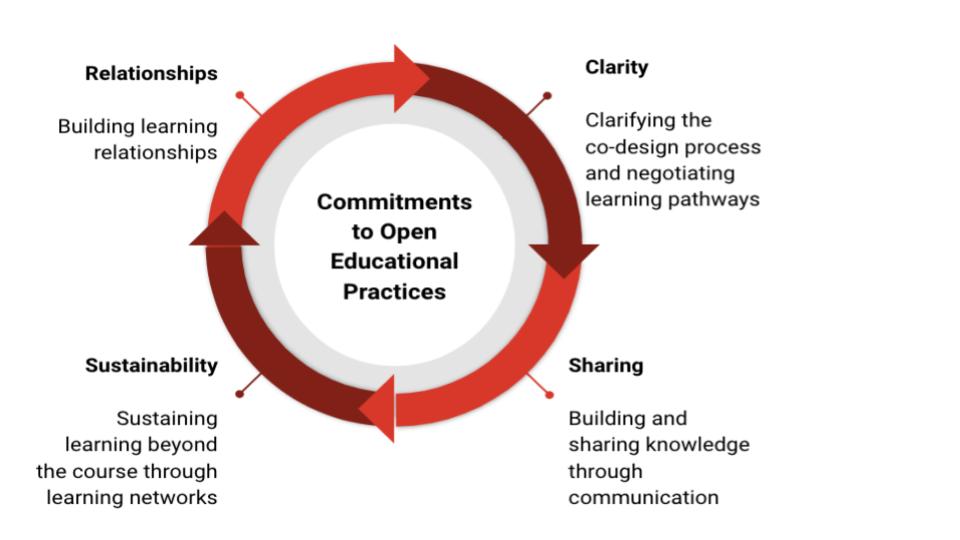

The OLDI framework has four interconnected stages with underlying reflective practice promoted throughout a learning experience. Stage 1 focuses on building relationships between instructors and students. Stage 2 outlines the co-design process and each learners’ personal learning pathway. This means that the instructor and learner work together to clarify and negotiate how the learner will demonstrate evidence of demonstrating competency in communicating the learning outcomes based on their personal learning needs and strategies for success. Stage 3 focuses on building and sharing knowledge and highlights how the learners choose to communicate their learning and thinking visibly and transparently with others. Finally, Stage 4 creates a bridge to sustain the learning beyond the course by developing and expanding upon personal learning networks. The introduction chapter provides an adapted version of the four-part open learning design framework.

It is the underlying open learning design principles that highlight and can provide one way to distinguish this course from other online courses. The principles of open learning design that guided my instructional design and teaching:

- Learning is dependent upon the opportunity for learners to co-design personally relevant learning pathways

- Learners collaboratively and individually share their learning experiences through open and closed feedback loops that include multiple people, spaces, perspectives, experiences and nodes of learning

- Learners need to transparently demonstrate their learning in meaningful ways that integrate curriculum and competencies

- Learning occurs through stages and continuums and is a personal learning experience that transcends formal learning environments

- Open learning emphasizes the learning process in order to build upon and share community knowledge (Roberts, 2019)

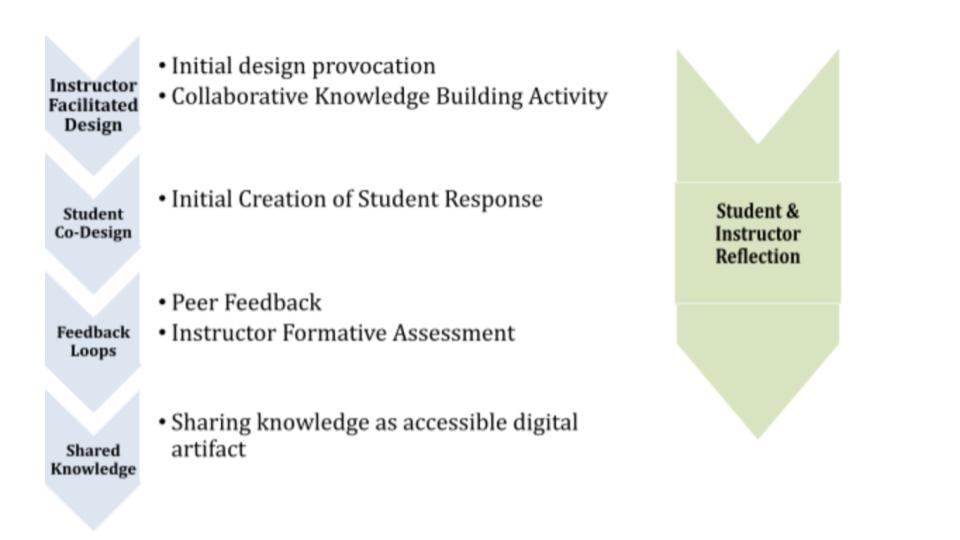

As illustrated in Figure 2, the principles of open learning design were embedded in the process from the instructor-facilitated design, student co-design expectations, multiple feedback loops and development of shared knowledge through digital artefacts (chapters). As an instructor, I continually reflected on my teaching and the learning design and at the same time students reflected on their learning. Figure 2 describes the learning framework for the #EdTechEthics course shared with students during a class in the Winter 2020 term:

When discussing the process with students I recognized the importance of connecting OLDI with the course learning outcomes and key topics. I recognized the need to amplify co-design in the learning process and to generate an open learning experience between the student, instructor, and outside learning community.

Organizing the Course into Key Topics

The course had an overall focus on educational technology and ethics. I found it useful to provide a guiding framework to students as a way to integrate content knowledge based on ethical positions and to share contextual examples that could help students with their own inquiry. Farrow’s (2016) Framework for the Ethics of Open Education was used to guide the key topics in the course, the course readings and guidance for the student inquiries and development of a chapter:

- Topic 1: Full Disclosure of Ethical Topics in Digital Learning Environments.

- Topic 2: Privacy, Data and Personal Security, and Informed Consent.

- Topic 3: Avoiding Harm, Minimizing Risk and Integrity.

- Topic 4: Respect for Participant Autonomy and Independence & Recognizing Bias

Modeling Open Education Practices

I noted that open publishing or sharing student work openly was likely something that a limited number of students may have experienced in the past. In many cases, graduate students in the teaching profession discussed how they asked their students to engage in similar learning activities; however, many graduate students noted they had never been asked to do the same thing themselves. I intentionally designed and integrated activities to help students build confidence, promote collaboration, feedback loops, and multiple ways to ask for help in order to learn using their own open pathway for the course, and potentially beyond the course.

I emphasized that every student in the course would have the option to publish their chapter in an open pressbook. Students were reminded they would have supports from their peers, instructor, program coordinator, and members of a research and project team as this process would continue after the course was completed. It was essential to always emphasize that the option to publish the chapter would be the student’s choice and there would be multiple opportunities to opt-in or opt-out before the final publication of the book. The students recognized that to ethically ensure that every student had the opportunity to make an informed choice as to whether or not they would openly publish their chapter, they also needed to fully understand the open learning process.

Boundary Crossing Between Informal And Formal Digital Learning Spaces

I used the institutionally supported learning management system and open digital tools and platforms to model how to learn within formal and informal digital learning boundaries and spaces. The course was completed over 12 weeks and each topic from Farrow’s (2016) Ethical Framework was allocated approximately 3 weeks. The learning management system was organized into weekly asynchronous modules to help the students find the readings and activities for each week. A Google folder was also used to share resources and students received weekly update emails to guide their weekly activities. I also created a course hashtag #EdTechEthics which was used for course activities and a way to build an openly networked community on social media platforms including Twitter. This provided students an opportunity to consider their digital identity and presence online, to build online relationships, and to connect with others outside of the course. Students were supported in developing awareness about their digital presence using White and LeCornu’s (2017) Visitor and Resident Map Tool and other open participatory activities throughout the course including considering personal data security and privacy (like reviewing the UBC Digital Tattoo Activities) in order to promote student choice in what they share, why they share it and whom they share as – in digital contexts.

Clarifying Open Learning Principles

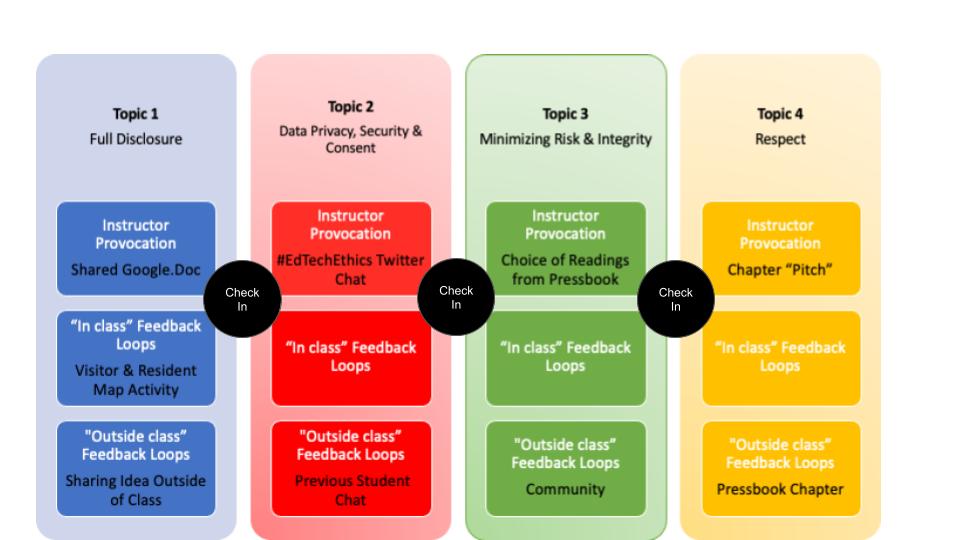

While Farrow’s (2016) Ethical Framework guided the course content, there were underlying open learning principles that promoted open readiness in order for the students to gain the confidence and readiness to share their chapters in an open pressbook. The students were asked to reflect upon their open learning experiences in a blog or final reflective assignment to ensure they made their thinking and learning visible to themselves, their instructor, and others. Figure 4 shows how the #EdTechEthics course followed the four key topics from the Ethical Framework, and integrated open learning activities (e.g., instructor provocations, ongoing feedback loops in the class, and external feedback provided by members outside of the class).

To ensure students had the opportunity to develop open readiness and confidence to share their chapters by integrating the open learning principles, the course activities were participatory, transparent, and helped model how to share, give and receive feedback while encouraging student reflection about their personal learning.

Figure 3 also highlights how the #EdTechEthics course was designed to adapt the OLDI framework, integrate the course content and key topics and design for specific activities to support the development of open readiness. Each topic also had a different audience in which to share and or give and receive feedback. For example, for Topic 1, students were introduced to emerging topics that considered the ethics of educational technology. The first week of the topic was guided by the instructor with the intention of providing a “hook” and provoking a reaction and challenge so the students could think about a topic in different and critical ways. In the second week, the students were given an open and participatory group activity to complete in small groups that I referred to as their social pods.

In the third week, the students were encouraged to share their reflections through personal blog posts or through conversations about their open learning process with others beyond the course walls (or class enrolment). For example, the students were encouraged to connect with the scholars who authored the articles included in their course readings as a way to connect with outside experts and learn more about their chapter topics in an authentic way.

As Figure 4 suggests, connecting open learning design with open co-design means supporting students to collaboratively and individually share their learning experiences through open and closed feedback loops. These feedback loops included multiple people, spaces, perspectives, experiences, and nodes of learning in formal and informal professional learning environments. The open learning principles helped the instructor to balance the focus on the completion of a chapter in an open textbook (learning product) with the awareness of the learning process. The principles promoted awareness about the open learning process, student choice about how to participate and contribute to a learning community, provided multiple mediums in which students could share and communicate their learning transparently, and ensured that they received and gave timely feedback in order to complete their chapters. The four topics from Farrow’s (2016) Ethical Framework and the iterative feedback loops within and at the end of each topic provided the students with timely opportunities to co-design their chapter and their learning pathway within the course.

Not only did I spend time designing for a course that met traditional constructive alignment guidelines (Biggs & Tang, 2011), I intentionally expanded upon more traditional guidelines by encouraging students to collaborate and connect with each other and those outside the course in order to build knowledge by sharing their experiences and ideas openly. This shift towards interdependence in learning provided the potential to explore the emerging open participatory co-design. The boundary between formal and informal learning was blurred as the learning activities within the course challenged learners to increase social interaction in multiple online spaces, communities, and networks.

Changes to Open Learning Design for 2021

Based on my personal teaching experiences and student feedback in the Winter 2020 term #EdTechEthics course, the following changes to the design were adopted in Winter 2021 term:

Assignment Expectations

Blogging was offered as an optional format that students could use for their reflections in the 2020 term. A few of the students used this format and I recognized the value in providing an open forum to reflect on the learning process during the course. In the 2021 term blogging became a main source for reflective practice for the students. I provided students with guidance for blogging by suggesting specific topics to consider when composing their blog posts. The blog posts were designed to help the students identify stages of open learner readiness (Cronin, 2017) which considered developing an awareness about their online identity, personal online privacy and security concerns, how to share content and ideas online and who to share with. The blogs also provided students with a venue to give and receive critical feedback to each other and receive feedback and guidance from their instructor. The ability to receive and consider critical feedback throughout the course seemed to help students when working on edits and feedback on their written chapters later in the course. Blogging also seemed to help foster and develop relationships between myself and the students. I would consider this an essential learning activity in shaping and negotiating personal learning pathways that helped support the co-design process.

Highlighting Open Learning Design Principles to Support ANY Learning Context

As mentioned in the introduction in this pressbook, the OLDI framework was adapted. Figure 5 depicts the four-part open learning design framework as commitments. Working with a collaborative team and embedding this work in a larger research project (Jacobsen et al., 2021) provided an opportunity to engage in dialogue and unpack the commitments of open educational practices. It is my hope the commitments can provide instructors with a frame that can be used, modified or adapted to support educational contexts.

Supporting Students’ Learning

Another area that I reflected on and aimed to improve was how to provide students with individual support. Students in the Winter 2020 term did not have an example of student-authored chapters on this topic. Students discussed their anxiety and fear of the unknown as they were assigned a learning task requiring them to co-design a pressbook chapter. In the following year, students in the Winter 2021 term were provided with a published pressbook as an example. They compared and contrasted their writing to what was previously done by former students and naturally used this as a target for their own work. I encouraged all students to meet with me individually for a check-in within the first two weeks of the course to discuss their ideas and provide personal support. I was able to connect and interact with every student in the first two weeks in a variety of ways such as zoom calls, email, and phone calls. These early check-ins with students helped me identify individual learning needs early in the course.

It can be challenging for one instructor to provide all the necessary support and feedback required for an inquiry and development of a chapter. I invited former students from the earlier term to serve as student-mentors. Many of my former students joined us for our synchronous course webinars and listened to the student pitches about their inquiry ideas. This helped the student-mentors recognize areas of connection and identify how they could offer support.

The synchronous webinars were scheduled several times during the course and proved to be an important part of the course that complemented the asynchronous weekly learning activities. The webinars included time for whole-class interactions and were intended to provide scaffolded support as students worked on their chapters. I tried to ensure the learning was chunked into smaller steps with manageable timelines so that everything was not completed at once. I also ensured that I clarified feedback expectations during the webinars to help students with goal setting.

As discussed earlier, the students were arranged in social pod groupings to help them connect asynchronously or synchronously and interact with each other throughout the course, to give and receive emotional learning support, and for feedback on their writing. Many students met weekly with their social pods, outside of any assigned course time, to work on the weekly course activities to gain valuable feedback and insights from their peers. The student-mentors who were invited to provide additional support during webinars were also invited along with other outside experts to join our class on Twitter. I attempted to create a safe space to practice interacting with others who may have different perspectives both within the class boundaries and in public spaces. Although many outside experts volunteered to join us for a webinar it was often difficult to schedule with a group. In some cases, I created a video for the students to view at an alternate time. The videos with outside experts provided a collection of webinars that were Creative Commons (CC) licensed. This provided a way to avoid scheduling repeated webinars. Asking outside experts to come into our course webinar, prepare a recording, or join us during a public forum to provide feedback and an expert perspective seemed to help validate the student work. This additional feedback possibly helped enhance the instructor and peer feedback that is normally provided within the boundaries of a class. In the Winter 2021 term, I opted to use more asynchronous options and created a course blog to share expert recordings, curated resources, content, and ideas to support students’ learning.

Future Considerations

Collaboration with Colleagues from Across the Program/ Faculty / University

Throughout this work, it became clear that I needed to depend upon other members of my university and learning community to provide students with the support needed to develop research and writing skills for drafting a book chapter. This included asking experts to come into the course to give the students feedback as their chapters progressed, librarians to help them with their research, the program coordinator to help connect and expand upon ideas in the other program courses as well as editing and feedback support from fellow colleagues to ensure the students received the content editing and copy editing they required.

Sustainable Projects

As I contribute to the final edits on this second volume of the pressbook with the co-editors, I wonder if the students need to write a whole chapter in order to experience open learning. The editing and feedback required to support multiple students may not be sustainable with larger class sizes. My interpretation of open learning design balances an emphasis on the learning process as well as a product. I think I would reconsider how many open learning activities like the social pods, Twitter hashtag integration, participatory online activities, and open webinars, that need to be included. I would also reconsider what kind of open educational resource we could co-design and possibly consider vignettes, cases, or shorter manuscripts for a sustainable open educational resource (OER) or end product.

Human-centered Pedagogy

The #EdTechethics courses were taught during the beginning of COVID-19 (Winter 2020) when on-campus courses pivoted to online learning and then again during the global pandemic (Winter 2021) when most graduate students were still studying fully online. While other instructors struggled to get their courses online, the courses in this graduate program were designed as fully online courses at the outset in 2017. The #EdTechethics course was already up and running in an online format. In both semesters, the students were most likely influenced by issues of equity and anxiety that prevailed across learning organizations during the global pandemic. I learned that it was not the online or on-campus medium or modality for learning that affected my students; it was the need for relationships with their instructor and their peers during an unprecedented time and context with unforeseen challenges. Students needed flexibility and they needed to know that they would be supported by their instructor. As I reflected on my course design and open pedagogical approach, I recognized that particularly in a time of crisis, students needed support for how to ask for help and where to find resources.

I look forward to future iterations of the course and I am extremely grateful to Dr. Barbara Brown, Christie Hurrell, Dr. Michele Jacobsen, Nicole Neutzling, Mia Travers-Hayward and all the students from both sections of #EdTechEthics for helping me learn so much about open learning design and the course that never ends!

References

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University (4th ed.). Berkshire, UK: McGraw Hill, Open University Press.

Brown, B., Roberts, V., Jacobsen, M., Hurrell, C., Neutzling, N., & Travers-Hayward, M. (2021, February 11). Leading and learning in a digital age: Open educational resource (OER) design and research. Invited keynote. Connecting Research to Practice 2021, Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, AB, Canada.

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 18(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Farrow, R. (2016). A Framework for the Ethics of Open Education. Open Praxis, 8(2), 93-109. https://openpraxis.org/index.php/OpenPraxis/article/view/291

Jacobsen, M., Brown, B., Roberts, V., Hurrell, C., Neutzling, N. & Travers-Hayward, M. (2021, June 17-18). Open learning designs and participatory pedagogies for graduate student online publishing. Proceedings of the Teaching Culturally and Linguistically Diverse International Students in Open and Online Learning Environments: A Research Symposium (pp. 1-8). International Teaching Online Symposium, University of Windsor, Canada. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/itos21/session3/session3/9/

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24783

Roberts, V., Wright, A., & Brown, B. (2021, November 16). Mobilizing Open at UCalgary: Introducing Open Educational Practices to Increase Access and Equity in Higher Education. Invited webinar guest, Open Pedagogy Community of Practice, University of Alberta.

Roberts, V., (2021, November 16). Mobilizing Open at UCalgary: Introducing Open Educational Practices to Increase Access and Equity in Higher Education. Invited webinar guest, Open Pedagogy Community of Practice, University of Alberta.

Roberts, V. (2019). Open educational practices (OEP): Design-based research on expanded high school learning environments, spaces, and experiences. (Doctoral dissertation). PRISM Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/handle/1880/110926

White, D., & LeCornu, A. (2017). Using ‘visitors and residents’ to visualize digital practices. First Monday, 22(8). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/7802/6515