Chapter 1: Ethical Considerations When Using Artificial Intelligence-Based Assistive Technologies in Education

Kourtney Kerr

Author Note

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning this chapter should be addressed to kourtney.kerr1@ucalgary.ca.

Educational Assistive Technologies That Incorporate Artificial Intelligence

As a society, we want to simplify tasks whenever possible. Individuals who use technological devices to make life easier are likely engaging with artificial intelligence (AI), which has computers performing tasks that traditionally required human intelligence (Congressional Research Service, 2018). Educational technologies continue to develop to assist student learning and achievement, and the integration of AI is becoming more common. The type of artificial intelligence with which individuals regularly interact is called ‘weak AI,’ as there are only one or two tasks that this AI performs (Johnson, 2020), and it is often in the form of machine learning. A video from the organization Code.org [New Tab] relays how AI operates and functions in terms of machine learning.

Machine learning relies on software to gain knowledge through experience. All machine learning programs are task specific. Such a program analyzes thousands of data sets to build an algorithm from patterns that would be less obvious to humans, and the algorithm is then adjusted based on whether or not the machine achieved its goal (HubSpot, 2017; Zeide, 2019). This cyclical process is then repeated, and the data sets in the program expand, which some describe as the program getting smarter. The algorithms on which many of these technologies operate are typically not disclosed to the users, but often student data and information is used to run them. AI-based assistive technologies that use weak AI are the ones that will be examined in this chapter, based on the question: What are the ethical considerations of using AI in the form of assistive technologies, and how are teachers and students affected, both positively and negatively, by the integration of these tools? This chapter will discuss different ethical concerns and possible solutions, along with the precautions teachers can take before implementing them in the classroom, and the ways in which students and teachers can use AI-based assistive technology tools to promote positive educational experiences.

Recent years have seen a marked increase in the number of products that use machine learning. AI is becoming more accessible to students, as mobile devices contain a voice assistant, and many devices found in technology-filled homes are programmed with similar functionality (Touretzky et al., 2019). As we continue to use them, the programs within these devices are always learning and always monitoring our choices. (Popenici & Kerr, 2017). Even though these systems are able to perform a wide array of functions to help make our lives easier, they do not have the ability to understand why we request these tasks; however, if we plan to use these programs in an ethical manner, we should know why they do what we ask of them (Atlantic Re:think, 2018). The ability of these programs to improve our lives is what makes them a beneficial technology to our everyday experiences, as well as our education systems. Table 1.1 identifies how AI-based assistive technologies incorporate multiple intelligences through the tasks they are able to perform.

| Intelligences that AI-based assistive technology is capable of performing | Intelligences that AI-based assistive technology cannot perform |

|---|---|

|

|

The inclusion of AI technology in the classroom can alleviate some aspects of a teacher’s workload and can also benefit student learning and achievement. Some AI that is available as assistive technology can be chosen and “tailored to fit individual student rates and styles of learning . . . but not replace the work of human teachers” (Johnson, 2020, para. 17), because teachers are better equipped to determine which teaching methods will meet the needs of each student. Teachers can work with machine learning technology to solve problems and challenges, and when used correctly, it can help their students become better learners and members of society (Atlantic Re:think, 2018; HubSpot, 2017). The following video examines how AI has developed to deliver personalized experiences and what considerations should be made as this technology continues to advance.

Video: Advanced Infographic, Hot Knife Digital Media Ltd., 2017

Appendix A is adapted from Farrow’s (2017) “Uncompleted Framework” (p. 103), which focuses on normative ethics in relation to educational research, and provides a summary of each section in this chapter. It can be used as a reference for the ethical considerations that teachers should make when using AI-based assistive technology with their students to promote enhanced learning experiences.

Full Disclosure for Using AI-Based Assistive Technology in Educational Settings

Identifying Assistive Technology Tools

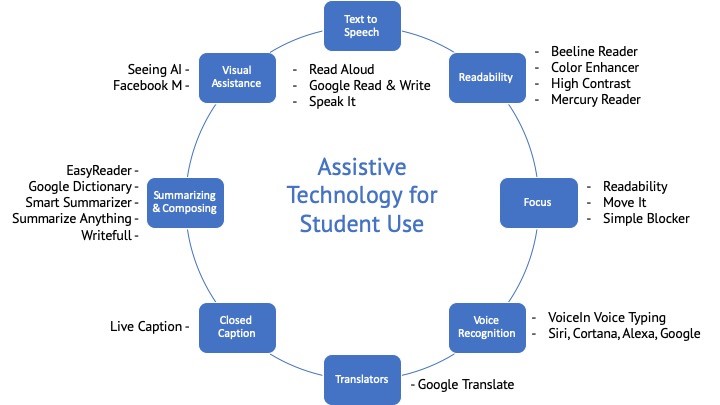

Teachers are constantly searching for methods to enhance students’ educational experiences, because all students have different requirements for their learning. Teachers often use digital technologies to give students access to various resources and materials to help them succeed and to support their diverse learning needs (McRae, 2015). Since assistive technologies are available for all students, these tools can engage students and assist teachers in meeting curricular goals, allowing them to be easily integrated into classroom environments (Sturgeon Public Schools, 2019). The majority of current educational artificial intelligence is provided through various software formats, making this technology more manageable and accessible in school settings (Zeide, 2019). Assistive technologies that use AI can also “significantly enhance student learning compared with other learning technologies or classroom instruction” (Holstein et al., 2018, p. 155), making them effective at improving student achievement. There are many different types of AI-based assistive technology, including applications (apps), extensions, and web-based programs; this allows students and teachers to choose the ones with which they prefer to work. Examples of these tools are identified in Figure 1.1.

All classrooms are diverse in the teaching and learning that occurs within them, and each one is personalized in some way. The inclusion of assistive technologies is one method for diversifying instruction and creating personalized learning environments; however, these tools cannot function in isolation and depend on teacher support (Bulger, 2016). Although expert teachers may seamlessly find ways to utilize these assistive technologies to maximize learning and resources, educators should remember that most of these “products are not field tested before adoption in schools and offer limited to no research on [their] efficacy” (Bulger, 2016, p. 11). This notion can raise concerns about how student data is being used or manipulated, and there is debate around the inclusion of AI-based assistive technologies in the classroom; while they have the “potential to revolutionize learning” (Bulger, 2016, p. 3), there is uncertainty regarding whether or not they can improve educational experiences and student achievement. As a result, AI-based systems should undergo more rigorous trials before being used in education, there should be standards in place for auditing AI systems, and ethical codes for using AI should be held to a high standard of accountability (Regan & Jesse, 2018). Teachers could also examine the following circumstances in which ethical concerns increase when using personalized learning systems:

- Teacher control or understanding of the program, app, or extension decreases

- Integration of the data collected by the company and classroom activities increases

- The type and amount of student data collected by the company increases

- Any data is used to refine software programs (Regan & Jesse, 2018)

Connecting with Policies and Procedures

School divisions in Alberta have policies and procedures that identify the need for students to have access to technology through networks and devices, with the main goal being to enhance learning through curricular connections. Many school divisions within Alberta are revising policies and procedures that are outdated or insufficient, to account for continually evolving educational environments that incorporate technology to enhance student learning (Wild Rose School Division, 2017). This acknowledgement is significant because of the ongoing modifications that could be made to accommodate these changes in technology and the ways in which technology can be used in educational settings. In some cases, school boards wish to collaborate with innovators in the technology sector to enhance the integration of technology in education (Edmonton Public Schools, 2020b). School divisions should ensure that student and staff security and privacy is maintained, and that data collection and usage is transparent, while integrating the use of technology. In doing so, school divisions are validating that their intention is to provide authentic experiences and to inform users out of respect for those using personal or division-approved devices within the classroom. This strategy could also imply that any assistive technologies permitted for a division’s use are scrutinized prior to their introduction, but that those chosen by a classroom teacher may not likewise be approved. As a result, teachers who choose a variety of assistive technologies for their classrooms may want to ensure that students and parents are fully aware of any privacy or security issues that could arise.

Students are also learning strategies they can use to protect their personal information and to maintain their safety when using division technology. This approach promotes independence and integrity in students as they become more responsible for their own digital undertakings. The incorporation of a variety of assistive technologies in the classroom promotes “ongoing support and opportunities for students to demonstrate their achievement” (Edmonton Public School Board, 2020d, Expectations section, para. 8), which is why teachers may find their inclusion beneficial. Since no students learn in exactly the same manner, teachers may want to apply their professional judgement to the various assistive technologies they choose to use with students. This judgement often involves ethical considerations that promote positive consequences within the classroom, such as allowing students to learn in a way that best suits their needs and experiences.

Teachers Using Assistive Technologies

The use of technology to enhance planning, support teaching, and improve assessment is also supported by policy, and could be a component of appropriate standards of practice for teachers in Alberta (Edmonton Public School Board, 2020c). Assessment policies often identify that assessments should be bias-free, “respectful of student differences, and reflective of the diverse student population” (Edmonton Public School Board, 2020d, Purpose section, para. 1, 3). Assessments that improve instruction to enhance student learning are part of responsive and ethical teaching, and this endeavour could be supported by the use of AI-based assistive technologies. Teachers can use these types of programs to grade student work; however, these programs do not currently apply to higher-level thinking and analysis skills, which means that the amount of time spent on these assessments cannot yet be adjusted (Johnson, 2020).

The ethical implications of allowing a computer to grade an assignment in which critical thinking is necessary are much greater, given the subjectivity of most written responses. Teachers are responsible for ensuring fair and equal treatment of all learners. Since assistive technologies would remove subjectivity and grade a written response assignment from an objective perspective, students who apply the strategies that the program recognizes as exemplary could unfairly benefit (Barshay, 2020). When using programs that grade multiple choice questions, the amount of input required varies. Teachers can determine which program best suits their needs and meets ethical criteria. Programs that require minimal personal information may be the better ones to choose in order to protect student information. Teachers often need to create an account to keep a record of student names with their scores, item analysis, and answer keys for each test, but the decision whether to use the program could be made by teachers, based on the terms of service or privacy policy. Other programs require teacher-created questions to be entered directly into the program along with the keyed response, and students need to log in to answer the questions before receiving a grade. This log-in data may be used for the purpose of benefiting the creator, or it could be sold to third-party distributors; thus, teachers may want to verify where this information is going and share these details with students before engaging with this form of AI-based assistive technology.

Maintaining Privacy, Data Security, and Informed Consent when Using AI-Based Assistive Technology

Meeting Expectations

Teachers at all grade levels are expected to include appropriate digital technology to meet student learning needs (Alberta Education, 2018), which means that all teachers should become familiar with the questions, concerns, and “debates surrounding the security and privacy of digital data…as soon no future educator will ever be separated from its presence” (Amirault, 2019, p. 59). AI-based assistive technologies are similar to many other digital services in that they collect and store personal information. Attempts have been made to limit the length of time personal information is stored, along with maintaining security measures and refraining from selling information as part of a voluntary student privacy pledge (Congressional Research Service, 2018). Since educational assistive technologies are used with students who are minors, the concerns that arise over privacy, data security, and informed consent are ones that should be mitigated, but there are differing opinions on how educational technology companies could be held accountable (Regan & Jesse, 2018). Information collected about an individual should be minimized to include only information that is required for the intended purpose and outcome (Regan & Jesse, 2018). The collection of student data should then occur only for the purposes of promoting student engagement and achievement. Further, student data collection should commence only once the individual knows that it is occurring and they have consented to the data collection. In a study conducted by Beardsley et al. (2019), nearly 75% of students are “actively sharing personal data with peers, companies and, often, publicly,” (p. 1030) even though the majority of these students “know they lack knowledge of responsible data management” (Beardsley et al., 2019, p. 1030). As a result, many students consent to the terms of use presented by a program or application without reading through the details contained within the document.

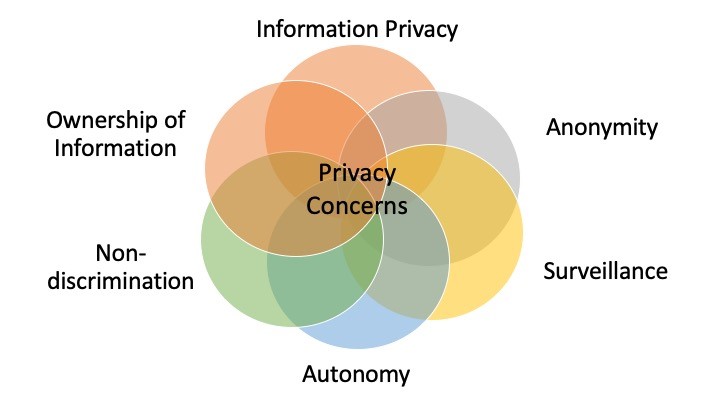

Teachers should ensure that students understand the consequences and outcomes they could experience when using assistive technologies in order to protect their privacy and data. Figure 1.2 displays the six privacy concerns teachers and students should be familiar with prior to engaging with digital technologies. To help protect personal information, teachers could also ask questions about data collection and security, especially if this information is unclear. They would then be able to determine whether or not this data collection benefits instruction or whether it is intended for surveillance (Bulger, 2016). This strategy can help promote transparency in terms of data collection and privacy and the impact that it has on students using these educational tools.

Tracking Information

Students are often interacting with AI-based programs in ways that reveal details about their responses to questions, how they process information, and their overall performance, and this collection may not attest to their achievement of learning outcomes (Bulger, 2016; Regan & Jesse, 2018). As a result, student information can be tracked in ways that do not enhance their educational experiences. Surveillance and tracking often require the collection of detailed information, which suggests that increased monitoring of students’ activities, and the usage of data generated from those activities, could negatively affect student and teacher engagement with assistive technologies (Regan & Jesse, 2018). A risk associated with using assistive technologies that rely on AI is that a multitude of data is now available to track students and their progress, which could lead to a focus on performance numbers and could impede overall student engagement or call into question teacher performance and effectiveness (Bulger, 2016). This outcome would not be in the best interest of students or teachers, which is why tracking information through AI-based assistive technologies could be detrimental to student achievement.

Effects on Teaching and Learning

Digital technologies should be used to support teaching and improve learning outcomes rather than to determine teacher effectiveness (Bulger, 2016). When teachers provide access to AI-based assistive technologies for their students, teachers may want to consider how these technologies could be used to improve teaching strategies, and if, or how, other students could benefit from these various supports. When using assistive technologies, there is often a lack of transparency and increased confusion over how data is collected and used, and who has permission to access this data (Bulger, 2016). If the information contained within the data can benefit student learning and achievement or benefit teaching strategies, then teachers should be able to access this previously collected data. Even though educational technology companies may intend to improve student achievement through data collection, biases can often exist or develop with AI technologies. Bulger (2016) mentions that “[d]iscussions of student data privacy address both data and privacy, but rarely focus on students, [and] the expectations and goals of personalized learning may not necessarily match the interests of students, parents, teachers, or even society” (p. 20). These concerns are valid, and teachers could decide which assistive technologies to use based on the goals for each student. If the benefits outweigh the downfalls, and allow students to develop skills that not only help them in the classroom, but in their personal lives as well, the assistive technology is likely suitable to use with students.

As much as teachers should be concerned about protecting student information when using assistive technologies in the classroom, there are some benefits to assistive technologies having this information. For example, while using predictive text or speech-to-text extensions, a student’s preferences can be saved, and the assistive technology can develop to become more accurate based on the input it receives. This process can enhance educational experiences as learning becomes more personalized for each student interacting with assistive technologies. School divisions can also access this information to determine which programs, apps, or extensions should be permitted to use within schools and on division-monitored devices. Where possible, teachers should take precautions to “protect [students’] personal information by making reasonable security arrangements against such risks as unauthorized access, collection, use, disclosure, or destruction” (Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, 2000, p. 42). Although students and teachers have concerns about privacy loss in the classroom, student data will likely continue to be collected on devices that are owned by the school division (Regan & Steeves, 2019). Greater transparency should exist about the purpose of this collection to identify whether information is collected and maintained by only the school division to improve student learning, or if it is shared with educational technology companies to enhance their own programs (or both).

Security and Personal Devices

Students are often encouraged to bring their own devices to school, as they are typically more familiar with them, but when using assistive technology programs or apps that have to be installed on the device, students’ personal information and data is likely much more accessible to educational technology companies. If students use their own devices, the privacy protection and security provided by school divisions may not exist to the same extent as it would if students were to use a device owned by the division; however, students who operate their own devices typically use the division’s internet. This access often allows certain apps, webpages, or extensions to be blocked to protect student information, which helps minimize the risk of data and/or security breaches. Certain programs can also be installed to protect student data and privacy from being obtained by unauthorized companies or users.

When students use AI-based assistive technologies, the data they generate on their personal device is “transmitted to a company who collects and stores the data, [which is then] permanently retained and tied to [that] specific, identifiable individual” (Amirault, 2019, p. 59). Teachers should allocate time to review terms of use documents with students, and allow them to make the choice as to whether or not they wish to download and operate certain assistive technologies on their personal devices. If the language used in any agreements is unclear, teachers may wish to speak with someone from the school division’s technology department to gain a better understanding. Teachers could then ensure that this information is clearly shared with students, using words they understand, so that they also know what they are consenting to prior to using assistive technologies. Teachers could also ask for parental input before moving forward. In order to ensure that consent is valid, a description of the potential risks and benefits should be presented in a manner that does not elicit a specific decision from those who could be affected by the use of these technologies (Beardsley et al., 2019; Miller & Wertherimer, 2011).

“Free” Usage and Data Collection

Many AI-based assistive technologies are free of charge for students and educators, but this unpaid usage may come at the cost of data collection (Beardsley et al., 2019). In the United States, “[w]ebsites that are collecting information from children under the age of thirteen are required to comply with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act” (Bourgeois, 2019, p. 141), which means that they need to do all they can to determine the age of individuals who access their sites. If an individual is under the age of thirteen, parental consent must be provided before any information about the individual is collected. Teachers should be cognizant of the efforts that educational technology companies make to follow this compliance, and should be more concerned about apps, programs, or extensions that collect student data but do not make an attempt to determine the age of students accessing these tools.

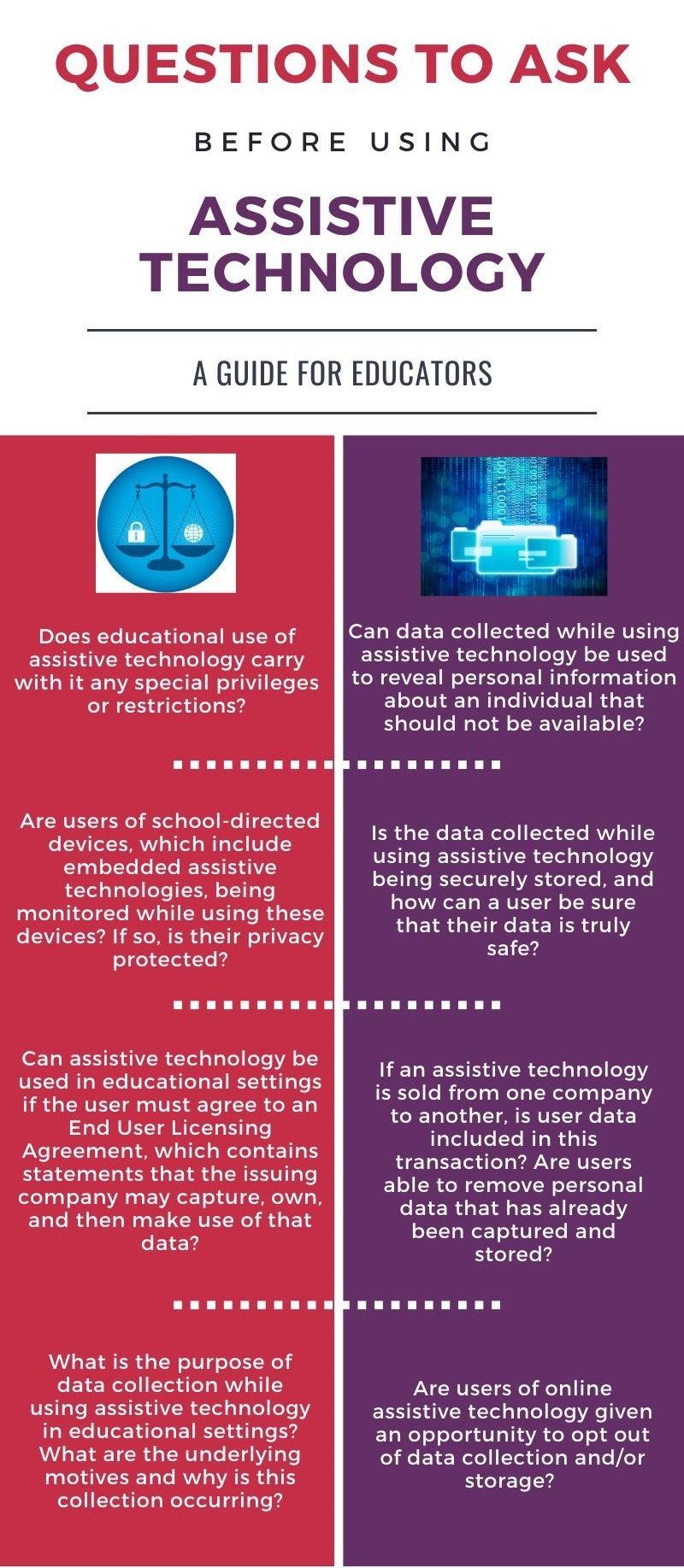

Teachers should also be aware that many companies require users to opt out if they do not want their information to be shared; therefore, by agreeing to use their tools, implied consent has been given to data collection and sharing (Bourgeois, 2019). If the company owns student data and information, they can choose to use this information as outlined in a usage agreement. The question arises of whether or not educational technology companies “should be able to use data generated by students’ use of their software programs to improve those programs” (Regan & Jesse, 2018, p. 173) and make students “test subjects for development and marketing of future edtech products” (Regan & Jesse, 2018, p. 173). Teachers should examine how student data is collected and used before allowing students to interact with AI-based assistive technologies in the classroom. In their review of educational technology companies, Regan and Jesse (2018) identified that “these companies are amassing quite detailed information on student demographic characteristics in their databases, as well as detailed information on student learning records” (p. 175). Although determining exactly which data points are collected and stored by companies who create programs, applications, or extensions for the purpose of assisting student learning could be challenging, teachers could review the details stated in user agreements to identify how data will be used before implementing them in the classroom. Figure 1.3 suggests questions that teachers could ask in regards to privacy and data security prior to engaging with AI-based assistive technologies.

Avoiding Harm and Minimizing Risk to Students Using AI-Based Assistive Technologies

Participating Anonymously

Students may wish to remain anonymous when using technology, to minimize risks that could bring them harm; however, AI-based assistive technologies need to collect some student information and data to support students in their learning, making anonymity difficult to procure. If students can use an assistive technology under a guest account, rather than creating a personal profile, this option may provide students with the anonymity they desire. Many Alberta school divisions assign students an account that includes their first and last name, followed by the school division’s domain. Each time students log in to a division-approved device with these credentials or run a program, app, or extension on that device, their personal information is shared or accessed, whether by the division or by educational technology companies. When students choose to use personal devices, their ability to remain anonymous in the eyes of the school division may exist; however, restrictions put in place by the division, “meant to protect students are much harder—if not impossible—to enforce when [personal] devices are involved and students no longer need the school network for access” (Cramer & Hayes, 2010, p. 41). Students’ private information may also be easily accessed by creators of assistive technologies when these tools are used on personal devices, if students do not have the proper securities in place. As a result, students could be harmed, as their personal details are being accessed.

Many students are unaware of strategies that exist to minimize their risks when participating in a digital environment (Beardsley et al., 2019). Teachers might want to discuss with students the details of their interaction with these technological tools, prior to having students sign up for assistive apps, programs, or extensions. Providing access to student information can be beneficial to student learning because the AI-based assistive technology knowledge base will continue to develop for each user as students engage with them; however, the benefits should outweigh the downfalls and minimize the risk of data or security breaches that could negatively impact students. The recommendation could also be made that neither teachers nor students create a personal profile for the purpose of using AI-based assistive technologies, unless the tool is supported by the school division, or the creation of a personal profile has been authorized by the students’ parents or the students themselves (Regan & Jesse, 2018). Students would still be able to benefit from the use of AI-based assistive technologies without the creation of a personal profile, but the personalization features that these tools are known for may decline. Students would also then have a greater level of protection when working with these online programs, apps, or extensions.

Recognizing Biases

AI-based technologies may be able to remove educator biases in regards to assessing student work, but there is still the potential for biases to exist and be unknowingly embedded by the developers of the technology, which can affect the way AI-based assistive technologies evolve (Regan & Jesse, 2018). These biases could include suggestions for other assistive technologies that are available for students, which could impact students in ways that discriminate based on various personal attributes, or those that are less obvious; therefore, these biases have the potential to put students and their personal information at risk. If students are profiled or tracked as a result of developer biases, and if student information is used in ways that are not transparent or are not beneficial to student learning, teachers may need to decide if the benefits of using the technology are worth the risks, and, if so, how these risks can be minimized (Regan & Steeves, 2019). In order to “use these systems responsibly, teachers and staff must understand not only their benefits but also their limitations” (Zeide, 2019, Promise and Perils section, para. 8), and clear procedures should be in place when discrepancies arise between assistive technology recommendations and teacher professional judgement. This recommendation suggests that teachers should be aware of the benefits and consequences of AI-based assistive technologies, and the extent to which students could be impacted, while ensuring that their own biases are not coming into play when determining what is best for their students. Along with biases related to assessment, teachers could also have biases regarding the assistive technology programs, platforms, or developers that they choose to use, in spite of the availability and accessibility of other options that could better support student learning. Teachers could spend time engaging with a variety of technologies before allowing students to do the same, in order to examine the potential consequences of various assistive technology tools. Although this process can become time consuming, it can also minimize or eliminate unwanted risks to students.

Another concern arises when educational technology companies gain influence over the individuals who engage with them (Popenici & Kerr, 2017) by providing limited options for assistance. This challenge is even more significant when students — who are typically minors — become influenced by these technological tools. Teachers should consider this shift in authority, as educational technology companies are often not held accountable for their biases toward student learning and the ways in which their assistive technologies support students’ educational experiences (Zeide, 2019). As a result of educational technology company biases and possible motivations to benefit the development of their programs, students could be using AI-based assistive technologies in ways that do not benefit their learning and instead make learning and achievement more challenging. Before teachers choose to include assistive technologies as supports for teaching and learning, they may want to consider the notion that students are not volunteering to provide analytics to educational technology companies, and they could consider whether or not the technological tools might work against student learning (Regan & Steeves, 2019). Either of these scenarios could place students’ personal information at risk and be detrimental to their learning experiences.

Are the Risks Worth the Rewards?

As with most teaching and learning strategies, teachers are asked to determine whether the benefits are greater than the detriments prior to introducing new strategies as part of students’ educational experiences. Provided that teachers have made this decision to the best of their abilities and in the best interest of the students, the benefits that can result from the incorporation of AI-based assistive technologies can be significant. Some of these include “more sophisticated analyses of student learning and testing, more personalized learning, more effective delivery of educational materials, improved assessment, and more responsiveness to student needs” (Regan & Steeves, 2019, “Tech Foundation Activities” section, para. 1). Many assistive technology tools can create these outcomes, as long as procedures are in place to protect students from damaging situations that could arise while using these tools.

Allowing for Student Autonomy and Independence when Using AI-Based Assistive Technologies

Considering Student and Teacher Choice

When students use AI in the form of assistive technology, they should be encouraged to set their own educational goals, which would allow them to advocate for themselves and to take more responsibility for their learning. Assistive technology tools are likely to become more effective when students use them to achieve these educational or learning goals, and students are able to become more autonomous when they act in an intentional manner and understand their choices (Beardsley et al., 2019). Teachers can provide many different options in terms of the assistive technology tools that are available, but the usage of these tools should not be mandatory if one objective is to promote student autonomy. Students should also be able to make choices for themselves regarding the assistive technology tools they choose to use, so that greater autonomy can be supported (Regan & Steeves, 2019). One form of AI-based assistive technology may work very well for one student, but may not provide the best assistance for another student. As a result, students should be allowed to voice their concerns about the tools that are offered and then be able to choose the one(s) that will help them achieve their goals.

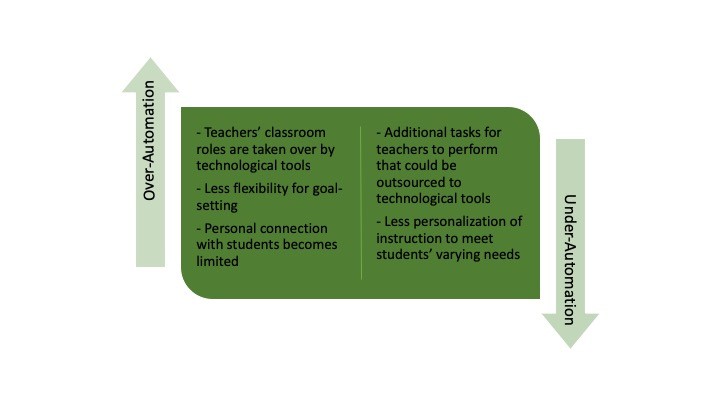

Holstein et al. (2019) mention that “[i]f new AI systems are to be well-received in K-12 classrooms, it is critical that they support the needs and respect the boundaries of both teachers and students” (p. 166). Not only should students be given the choice of which assistive technologies they use; teachers should also be able to have their voices heard regarding which assistive technologies could be supported and utilized by their school divisions. Teachers regularly make decisions regarding which tools will best enhance their teaching practices and which will provide the best learning opportunities for their students, so leaving the decision about which technological tools to use in the hands of those who are not in the classroom may provide less than mediocre educational experiences. The ability to decide how much integration of these tools is necessary to benefit both student achievement and teacher roles and responsibilities should also be controlled by classroom teachers. Since teachers know how best to meet the needs of their own students, they should be permitted to find a balance between over- and under-automation and autonomy within their classrooms, which is reflected in Figure 1.4.

Promoting Independence and Participation

Many AI-based assistive technology tools make recommendations for students based on how others with similar data profiles previously performed (Zeide, 2019), which suggests that students could be manipulated easily by these technologies. Understanding how assistive technology tools make these determinations is not knowledge that could be acquired easily by teachers and students. Consequently, teachers and students should be encouraged to work with assistive technology tools that promote self-interest and avoid unfavourable outcomes (Regan & Jesse, 2018). The opportunity to act in such a way would further promote student independence and may lead to students engage with AI-based technologies outside of the classroom in a much more comfortable and confident manner (Cramer & Hayes, 2010). The skills students learn while using these tools could also increase student participation and engagement with AI-based assistive technologies. Improving teacher and student understanding of how these technological tools operate can promote higher-level thinking and achievement, and can empower teachers and students with more knowledge to help them as technology continues to evolve (Milanesi, 2020). When students use assistive technologies to help them achieve their educational goals, they can receive assistance from both the technological tool and the teacher, which can further encourage active participation and support varying student needs.

Conclusion

As technologies that use a form of artificial intelligence become more prevalent in society, the education system could see a marked increase in the inclusion of AI-based technologies in the classroom. Assistive technologies that use a form of AI may increase student engagement more than assistive technologies that do not include an AI component. Many programs, apps, or extensions that constitute AI-based assistive technologies do not undergo rigorous trials before being implemented in schools, so teachers and students are often test subjects for educational technology companies that design and administer these tools.

Technology inclusion is becoming an increased priority in many school divisions, so the maintenance of teacher and student privacy and security when interacting with AI-based assistive technologies should be a primary concern. Student information that is collected or shared with educational technology companies should be minimized, and should only include information that allows for improvements to be made to student engagement, learning, and achievement.

Teachers can help students protect their personal data by ensuring that personal profiles — to which educational technology companies have access — contain as little identifiable information as possible. Parental support for the use of assistive technologies could also be obtained, and school divisions could generate student log-in information that does not expose students’ identities. Students using personal devices should take additional measures to ensure that their privacy and security is maintained. If student performance or information is tracked by school divisions or educational technology companies, teacher effectiveness could be questioned, and biases based on profiling could prevent students from achieving to the best of their abilities.

Allowing students to choose the assistive technology tools that could help them achieve their educational goals can promote greater independence and autonomy. When students can act in ways that promote their self-interest and help them achieve success, they are more likely to become engaged with technology and to have a better understanding of how it can assist them in their lives beyond the classroom. Respecting student boundaries and limitations when working with technology is important, as is allowing teachers to invoke their professional judgement when identifying the assistive technology tools that work best for their students and in their classrooms. Before implementing assistive technologies that operate with a form of artificial intelligence, the benefits to student learning should be clear, along with the potential drawbacks to teaching and learning that could result.

Questions for Future Research

- As teachers and school divisions gain valuable knowledge about the intentions of educational technology companies, should more control be given to learners and educators to make decisions about which AI-based assistive technologies are best for their own learning experiences?

- Considering the breadth of assistive technologies that are available, should school divisions or other educational bodies create a list of approved assistive technologies for teachers, in order to prevent teacher burn-out or lawsuits due to misuse?

- Many teachers are not experts in every educational technology used for learning, so in what ways can professional learning for teachers align with the ever-evolving world of AI in education?

- As AI continues to advance, what expectations will arise regarding the use of AI technology to run assistive programs, applications, or extensions in educational settings?

- In what ways can school divisions and educational technology companies provide greater transparency about the amount and type of data they collect, along with how/why it is collected and how this data is used?

- In what ways can teachers and students be empowered to make decisions about the collection of data, and also to challenge the data that has been collected on them?

References

Alberta Education (2018). Teaching quality standard. https://education.alberta.ca/media/3739620/standardsdoc-tqs-_fa-web-2018-01-17.pdf

Amirault, R.J. (2019). The next great educational technology debate: Personal data, its ownership, and privacy. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 20(2), 55–70. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=139819560&site=ehost-live

Atlantic Re:think. (2018, June 29). Hewlett packard enterprise — Moral code: The ethics of AI [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/GboOXAjGevA

Barshay, J. (2020, January 27). Reframing ed tech to save teachers time and reduce workloads. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/ai-in-education-reframing-ed-tech-to-save-teachers-time-and-reduce-workloads/

Beardsley, M., Santos, P., Hernandez-Leo, D., & Michos, K. (2019). Ethics in educational technology research: Informing participants on data sharing risks. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(3), 1019-1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12781

Bourgeois, D. (2019). The ethical and legal implications of information systems information systems for business and beyond. In D. Bourgeois (Ed), Information Systems for Business and Beyond. Pressbooks: Open Textbook Site. https://bus206.pressbooks.com/chapter/chapter-12-the-ethical-and-legal-implications-of-information-systems/

Bulger, M. (2016). Personalized learning: The conversations we’re not having. Data and Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/pubs/ecl/PersonalizedLearning_primer_2016.pdf

Code.org. (2019, December 2). AI: What is machine learning? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OeU5m6vRyCk

Congressional Research Service. (2018). Artificial intelligence (AI) and education. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF10937.pdf

Cramer, M., & Hayes, G. R. (2010). Acceptable use of technology in schools: Risks, policies, and promises. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 9(3), 37-44. https://doi.org/10.1109/mprv.2010.42

Edmonton Public School Board. (2020a, January 29). Appropriate use of division technology. https://epsb.ca/ourdistrict/policy/d/dkb-ar/

Edmonton Public School Board. (2020b, January 29). Division technology. https://epsb.ca/ourdistrict/policy/d/dk-bp/

Edmonton Public School Board (2020c, January 29). Division technology standards. https://epsb.ca/ourdistrict/policy/d/dk-ar/

Edmonton Public School Board. (2020d, January 29). Student assessment, achievement and growth. https://epsb.ca/ourdistrict/policy/g/gk-bp/

Farrow, R. (2016). A framework for the ethics of open education. Open Praxis, 8(2), 93-109. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.2.291

Freedom of information and protection of privacy act. Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000, Chapter F-25. https://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/F25.pdf

Holstein, K., McLaren, B., & Aleven, V. (2018). Student learning benefits of a mixed reality teacher awareness tool in AI-enhanced classrooms. In C. P. Rosé, R. Martínez-Maldonado, H. U. Hoppe, R. Luckin, M. Mavrikis, K. Porayska-Pomsta, B. McLaren, & B. du Boulay (Eds), Artificial Intelligence in Education Part 1 (pp. 154-168). Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007 /978-3-319-93843-1

Holstein, K., McLaren, B., & Aleven, V. (2019). Designing for complementarity: Teacher and student needs for orchestration support in AI-enhanced classrooms. In S. Isotani, E. Millán, A. Ogan, P. Hastings, B. McLaren, & R. Luckin (Eds), Artificial Intelligence in Education Part 1 (pp. 157-171). Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23204-7

Hot Knife Digital Media ltd. (2017, May 12). Advanced infographic [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/217148732

HubSpot. (2017, January 30). What is artificial intelligence (or machine learning)? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/mJeNghZXtMo

Johnson, G. (2020, January 12). In praise of AI’s inadequacies. Times Colonist. https://www.timescolonist.com/opinion/op-ed/geoff-johnson-in-praise-of-ai-s-inadequacies-1.24050519

McRae, P. (2015). Growing up digital: Teacher and principal perspectives on digital technology, health and learning [Infographic]. https://www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/About/Education%20Research/Promise%20and%20Peril/COOR-101-10%20GUD%20Infographic.pdf

Milanesi, C. (2020, January 23). Can AI drive education forward? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/carolinamilanesi/2020/01/23/can-ai-drive-education-forward/#57b976ea7964

Miller, F. G,. & Wertheimer, A. (2011). The fair transaction model of informed consent: An alternative to autonomous authorization. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 21(3), 201–218. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/docview/903663594?accountid=9838&rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo

Popenici, S.A.D., & Kerr, S. (2017). Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning 12(22). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-017-0062-8

Raj, M., & Seamans, R. (2019). Primer on artificial intelligence and robotics. Journal of Organizational Design, 8(11), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41469-019-0050-0

Regan, P. M., & Jesse, J. (2018). Ethical challenges of edtech, big data and personalized learning: Twenty-first century student sorting and tracking. Ethics and Information Technology, 21(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-018-9492-2

Regan, P. M., & Steeves, V. (2019). Education, privacy, and big data algorithms: Taking the persons out of personalized learning. First Monday, 24(11). http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5210/fm.v24i11.10094

Roberts, R. (2018, April 8). A.I. and multiple intelligences. Scribal Multiverse. http://www.scribalmultiverse.com/a-i-and-multiple-intelligences/

Sturgeon Public Schools. (n.d.). Digital resources for learning. https://www.sturgeon.ab.ca/Digital%20Resources.php

Touretzky, D., Gardner-McCune, C., & Martin, F., & Seehorn, D. (2019). Envisioning AI for K-12: What should every child know about AI? Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 33(1), 9795-9799. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33019795

Wild Rose School Division. (2017). Administrative procedure 143 technology standards – Computer/peripheral hardware standards. https://www.wrsd.ca/our-division/administrative-procedures

Zeide, E. (2019). Artificial intelligence in higher education: Applications, promise and perils, and ethical questions. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/ articles/2019/8/artificial-intelligence-in-higher-education-applications-promise-and-perils-and-ethical-questions

Appendix A

| Principle | Duties & Responsibilities (deontological theory) | Outcome (consequentialist theory) |

Personal Development (virtue theory) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full disclosure |

|

|

|

| Informed consent |

|

|

|

| Privacy & data security |

|

|

|

| Avoid harm/ minimize risk |

|

|

|

| Respect for participant autonomy |

|

|

|

| Integrity |

|

|

|

| Independence |

|

|

|

Media Attributions

- Figure 2 © Kourtney Kerr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 3 © Kourtney Kerr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 4 © Kourtney Kerr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Balancing automation and autonomy. Adapted from Holstein, McLaren and Aleven (2019). © Kourtney Kerr is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license