Chapter 2: Beware: Be Aware – The Ethical Implications of Teachers Who Use Social Networking Sites (SNSs) to Communicate

Heather van Streun

Author Note

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning this chapter should be addressed to htumbach@gmail.com.

Introduction

As teachers strive to build productive and positive relationships with their students, parents, and colleagues, they may employ different techniques to do so. The main reason behind developing effective relationships with these stakeholders is to put students at the forefront of authentic learning. It is recognized that strengthening relationships with parents, students, and even colleagues can be one way to support student learning (Alberta Government, 2018). One of the most critical ways to foster strong relationships is through effective communication (White, 2016).

Teachers are tasked with sharing a multitude of information from events, field trips, and student learning progress to professional learning opportunities and resources. Known as command communication (White, 2016), teachers communicate “in clearly prescribed ways” (p. 70) using tools such as email, websites, and newsletters. As White (2016) points out, “[w]ritten communication is probably the most efficient and effective way teachers provide clear information” (p. 70). Teacher communication is not limited to the command function, but also to a relational function, which is the “basis of effective learning relationships and enables the development of communities of practice, dialogues, and fusions of horizons” (White, 2016, p. 71). Teachers can communicate with both functions to “maximize sharing of information and understanding” (White, 2016, p. 70). This can be challenging to accomplish, but with the integration of technology, teachers build relationships and communities, encourage dialogue, share information and overcome the barriers of time, distance, and even languages. Social Network Sites (SNSs), such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, lend themselves as a platform to achieve strong teacher communication to build and strengthen relationships.

| Users connect and share various media, such as text and pictures, with followers, who are known as ‘friends’ online. Friends can comment on user posts. | |

| Users post 140-character messages (tweets) to followers. Tweets can be commented on and shared. Private messages are also available. | |

| Users share with followers photos and videos that can be commented on and shared. Altering or filtering is a common practice by users. |

Ethical Considerations of SNSs Use in K-12 Classrooms

This innovative use of SNSs creates ethical dilemmas for educators. From the lens of a consequentialist approach, “teachers are in a difficult position of trying to innovate in their classroom using SNSs while at the same time being conscious of the risks” (Henderson, et al., 2014, p. 2). This chapter will navigate the ethical implications teachers face when using SNSs to communicate the learning that happens in their classrooms.

The framework for teachers using SNSs for communication, adapted from Farrow’s (2016) OER Research Hub project, identifies the three normative ethical theories and highlights considerations for teachers who do engage with SNSs for communication purposes (Table 2.2). These ethical perspectives attempt to guide how teachers and students can and should behave, which rules and procedures they should adhere to, and which beliefs and values teachers should have (Farrow, 2016). SNSs used in the classroom context can be powerful, but what are the implications of balancing the pressure and desires to use social media for communication from our colleagues and parent community with the ethical expectations of the teaching profession?

| Principle | Duties & Responsibilities (deontological) | Outcome (consequentialist) |

Personal Development (virtue) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full disclosure |

|

|

|

| Privacy & data security |

|

|

|

| Informed consent |

|

|

|

| Integrity |

|

|

|

| Avoid harm/minimize risk |

|

|

|

| Respect for participant autonomy |

|

|

|

| Independence |

|

|

|

Full Disclosure

As teachers join the growing movement of using SNSs for their classroom communication (Auld & Henderson, 2014), there are expectations placed on them by their principal, districts, and professional bodies. Even though not explicitly defined, these expectations contain Nias’ (1999) six components of a culture of care, which include: being affective, responsibility for learners, responsibility for relationships in the school, self-sacrifice and obedience, over-conscientiousness, and identity (Figure 7.1). Teachers who use SNSs should employ a due culture of care to ensure that they meet the professional expectations placed upon them. This culture of care should include an evaluation of the consequences of using SNSs, followed by the disclosure of the consequences and pertinent information to the parties involved, including parents, students, and colleagues.

Luckin et al. (2009), as cited in Howard (2013), suggest that “[t]o facilitate effective use of Web 2.0 technology in the classrooms, teachers are encouraged to be willing to embrace risk and to consider small ways of navigating existing cultures and reframing old contexts to incorporate new ones” (p. 44). As teachers transform the purpose of SNSs to fit their classroom contexts, they should consider the notion of full disclosure, which is when the teacher makes all information and facts known (Oxford University Press, 2019). The following section will examine two components to this disclosure: teacher communication expectations and the use of personal learning networks to share and co-construct knowledge.

Teacher Policies and Procedures

Regardless of whether or not a teacher participates in SNSs, there are policies and procedures to which they must adhere to as a member of a professional association, not only for their own professional protection but also for the protection of colleagues, students, and parents. By following the specified policies and procedures for communication, teachers meet the aspects of a culture of care.

Teachers in Alberta, for example, are required to follow the ATA Code of Conduct, the Teaching Quality Standards, Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, and their own district’s Administrative Procedures. These guiding documents define what data and information teachers have access to, who can provide permission to use the platform, and how they can use it to support the learning that happens in their classrooms.

Due to the openness and highly connected nature of SNSs, teachers should communicate to parents, students, and colleagues (including administration) which SNSs they are using and their purpose for using those platforms. As well, teachers should notify stakeholders what they will be posting, before they post it. This will give parents and students opportunities to have input and the ability to give or refuse consent. As Henderson et al. (2014) point out, “teachers should be aware that this consent might need to be renegotiated at regular intervals” (p. 3). Auld and Henderson (2014) also argue that teachers have the responsibility to ensure that students (and parents) want their own virtual identities to be made public when using SNSs as a tool for communication. As students or parents comment on a post, they are at risk of exposing their online identity which they may not have considered.

Sharing and Co-Construction of Knowledge Through Personal Learning Networks (PLNs)

Many professionals have been adapting and adopting various emerging practices, such as using SNSs, to network, share, and co-create knowledge (Veletsianos, 2016). Teachers may find themselves using SNSs in the classroom for the same purposes, while guiding students in developing the skills to participate effectively in Personal Learning Networks (PLNs). “Research that suggests that such platforms can facilitate the shared construction of knowledge and peer interactions that support learning adds to the perception that SNSs, such as Facebook, could be a catalyst for classroom engagement and collaboration” (Howard, 2013, p. 43). Whether it is a teacher’s own PLN with other professionals or a student-based PLN, teachers should disclose what they, themselves, are gaining from integrating SNSs as a modality. As Auld and Henderson (2014) identify, “[t]eachers need to consider what the implications are for co-inhabiting spaces that are designed to connect people and share information” (p. 199); however, disclosure of benefits should not be limited to the teacher viewpoint. Emphasis should also be placed on the student viewpoint. What does the student have to gain or lose by participating in a PLN via SNSs? What opportunities and guidance will students (and parents for that matter) have to participate in PLNs? What opportunities exist to be part of a PLN if parents do not want to use SNSs? These are all aspects of full disclosure that teachers should consider and communicate.

As teachers disclose the purpose for using SNSs in their classroom practice, they should consider the six aspects of the culture of care. By keeping these practices student-centred, the argument could be made that the choices the teacher is making to build relationships and enhance communication are inherently good. By having an environment that is built on full disclosure, teachers will continue to build “a sense of community, people-making, and dialogue” which is foundational to school-family partnerships (White, 2016, p. 69).

It should be recognized that full disclosure should not be limited to the intent and should also include other considerations such as privacy and security. The next section will explore these elements and the ethical dilemmas they create.

Section 2: Privacy, Data Security, and Informed Consent

When it comes to the role of the teacher, and protection of privacy, evolving technology has created a need for privacy and security awareness. As mentioned in the previous section, teachers must follow various policies and procedures, such as the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FOIP) [New Tab] (Alberta Teachers Association, 1999), which is a legally binding document and mandatory. In this particular act, “the privacy of students and parents is protected by rules that school [administrative procedures] must follow in the collection, use, protection and disclosure of personal information” (para. 4). While engaging on SNS platforms, teachers may expose themselves, students, and parents to breaches of privacy and careless consent to the collection of data. In their paper, Regan and Jesse (2019) explored the ethical concerns of privacy in 21st-century learning and identified six distinct ethical concerns. The following section will explore three of the six privacy and data security concerns when teachers post and share content on SNSs.

Information Privacy

When posting any content online, there is exposure and formation to one’s identity. Regardless of whether a teacher creates a digital identity to connect with PLCs, share lessons, or celebrate the connections in the classroom, there is a tension between confidentiality and transparency. Teachers may carelessly expose themselves, parents, and students to the collection of data.

Teachers can enlist proper attitudes that help limit exposure. Summarized by Regan and Jesse (2019) as, “notice, consent, choice and transparency” (p. 170), when posting any information online, teachers are responsibility to those parties involved (students, parents, colleagues, etc.) to communicate the purpose and content of the post, to seek consent, and to allow those involved to choose what is posted or to be removed from the post, and to be able to see the post after submission.

Ownership of Information

Once content is posted, who owns the post and its contents? The answer depends on the SNS platform and its privacy policy. When looking at a privacy policy, or reading the terms of service before clicking accept, one may notice that these are long and complex documents. Readers can become lost in jargon, and, as a result, users accept the agreements without becoming aware of critical information, such as data collection and ownership of information. For example, Facebook’s Privacy Policy [New Tab], which also includes Instagram, explains ownership of information.

According to Facebook (2019), “you own the intellectual property rights (things such as copyright or trademarks) in any such content that you create and share on Facebook” (“Your commitments” section); they go on to identify that if users share, post, or upload content, Facebook is granted the permissions to use, distribute, modify, copy, and create derivative products of the content. If a teacher posts a picture of students working in the classroom, the teacher has given Facebook and Instagram the ability to “store, copy, and share it with others” (Facebook, 2019, “Your commitments” section) based on the privacy settings. Even when parents grant permission to use photos of their child, they may not understand that the child’s photo may be used by third-party companies, based on the SNS platform. Students should be consulted when their work will be posted on SNSs, as they own the intellectual property rights to their content, and they may not want to give those platforms the ability to remix and reuse their work.

Understanding the agreements of SNS platforms is crucial to effective communication practices. Some may consider the practice of deleting the content after the school year is over, as those students move on to another classroom; however, teachers should be aware of the adage ‘once online, always online.’ Facebook identifies that if the content is deleted by the user, it will be removed from Facebook’s systems, though it may exist elsewhere (2019). As Molnar and Boninger (2015) point out, “[e]ducators are obliged not only to learn how student data may be gathered and exploited but also to develop privacy policies that protect their students from such exploitation” (p. 8).

Surveillance – AI

It would be naive to believe that one’s online presence is not tracked in some form or another. “Tracking software also records adult behaviour on the Internet, of course, although many adults may be unaware of it. Since educators are, however, responsible for the children entrusted to their care, they cannot afford to be uninformed about potential threats to student privacy” (Molnar and Boninger, 2015, p. 8). As soon as a teacher engages with SNSs, there is surveillance of their activity and that of the users to whom they are connected. For example, as soon as the student does connect to the content posted on the teacher’s SNS, marketers can track the student’s online activity and direct ads to that student (Molnar and Boninger, 2015, p. 7).

Even as teachers consider information privacy, ownership of information, and surveillance, they may still fail to protect all invested parties’ privacy. A common phenomenon exists known as the Privacy Paradox. First discussed by Barnes (2006), the Privacy Paradox identifies that there is a contradiction between online behaviour and privacy concerns (Table 2.3). The research conducted by Dienline and Trepte (2014) showed that people on SNSs “engage in self‐disclosing behaviours that do not adequately reflect their concerns” (p. 285). “Despite privacy concerns, users, most of the time, fail to protect their privacy within SNSs, thus putting themselves and other users at risk” (Sideri, et al., 2017, p. 79).

| 4 Privacy Paradox Phenomena of Social Network Sites |

| 1. Large quantity of information disclosed online |

| 2. The illusion of privacy |

| 3. Discrepancy between context and behaviour (even when known to be public, act like SNSs are private) |

| 4. Users’ poor understanding of data processing actions by online businesses |

Knowing the phenomena, teachers can act in an ethical manner that ensures the protection of privacy to the best of their ability. Prior to the first post, teachers should read the privacy policy and terms of service of their chosen platform. They can then act according to what they are comfortable with and what is best for all users involved in the communication. Also, informing parents and students of the terms and allowing them to create their own limitations of content to be posted, would reduce the breach in privacy and data collection from the post.

In the end, even with instilled practices to limit the accessibility of data or enable privacy features, these features may dissolve at any point, leading to the risk that the content become public (Auld & Henderson, 2014). It is this point that leads to the exploration of what the teacher can do to maintain educational integrity by avoiding harm and minimizing risk.

Educational Integrity by Avoiding Harm and Minimizing Risk

When parents send their children to school, they entrust educators to provide quality education while ensuring that their child is cared for and protected. Known as in loco parentis, the teacher is in place of a parent and is given the same rights and responsibilities (Law Now, 2019). In Alberta, according to the competencies in the Teaching Quality Standard (2018), teachers are expected to “recognize that the professional practice of a teacher is bound by standards of conduct expected of a caring, knowledgeable and reasonable adult entrusted with the custody, care or education of students” (p. 3). When teachers engage in posting on SNSs, this care should still be practiced. As teachers aim to maximize the benefits of using SNSs as a form of communication, they should also take measures to minimize the potential risk of harm to themselves and those with whom they interact. This section will look at opportunities educators have to maintain educational integrity while avoiding harm and reducing risks when engaging in online communication.

Modelling Digital Communication

Teachers are held in high regard in society, and what they do in their personal lives will usually be viewed with a lens that relates to the profession. “The teacher acts in a manner which maintains the honour and dignity of the profession” (ATA, 2018, standard 18). This also applies to the teacher’s interaction with SNSs. Whether being used to connect with other teachers in PLCs, with parents and students, or with friends and family, “teachers need to maintain a respectful and professional identity” (Planbook.com, 2018, Section 1, para. 4).

In 2012, George Couros, an educator and recognized keynote speaker for professional audiences, posted a blog titled “Personal and Professional vs. Public and Private” [New Tab]. He discussed the debate of teachers having a personal SNS account separate from a professional account. His argument is that whether teachers have separate accounts or not, there is the potential for anyone to see the posted content. “What I am always aware of is that no matter who sees what I put out there, anyone can see it eventually, whether it is through me or someone else” (Couros, 2012, Section 1, para. 4). In fact, by combining the personal and professional accounts into one, teachers have a unique opportunity to model effective digital citizenship and digital literacy skills to their followers, which may include parents, students, and other teachers, rather than letting them figure it out on their own (Howard, 2013).

Setting Expectations

By communicating expectations for parents, students, colleagues, and themselves, teachers can reduce the risks that come with engaging in SNSs. “Even if we deem the benefits of SNSs worth the potential risks, a plan for managing those risks is warranted” (Howard, 2013, p. 44). It is interesting to note that due to the recent COVID-19 crisis (Spring 2020), educators have found themselves needing to turn to emerging technologies such as SNSs to communicate effectively with students and parents. If they do not set up expectations from the beginning of the school year, teachers may struggle with boundaries and guidelines for themselves, parents, and students. Teachers should look to their guiding policies and procedures to provide support for navigating this challenge. However, it is recognized that with the fast pace of technological change, these policies and procedures may need constant revision to remain current.

Many school districts have developed administrative procedures that identify the expectations of all parties involved with using SNSs. As Howard (2013) points out, “[p]olicies that prevent private one-to-one communication between teachers and students that do not generate a permanent record are extremely important to ensure the public’s trust that the users of these networks are operating above-board” (p. 50). For example, Elk Island Catholic Schools (2019) has Administrative Procedure 146, titled “Social Media”, which identifies expectations for division staff, students, and parents (Table 2.4).

| Procedures |

|---|

| 1. Principals shall: |

| 1.1 Ensure students, parents, and staff are aware of the Division’s expectations for responsible use of Social Media. |

| 1.2 Encourage parents to communicate to school personnel any concerns they may have about inappropriate use of Social Media. |

| 1.3 Ensure students, parents, and staff are educated in the appropriate use of Social Media and the associated benefits and dangers of a public online presence. |

When teachers do set guidelines for how SNSs will be used, they should include expectations for:

- Timeliness of posts

- Expectations and moderation of responses

- Procedures for one-to-one communication

- What will happen to content after the school year is over

- Limitations to having followers and following back

Teachers who model effective use and positive communication skills with SNSs remain consistent with the rights and responsibilities placed upon them as professionals. Each post should be considered an opportunity to develop digital literacy skills for teachers, students, and parents. By setting and following expectations, all stakeholders will reduce risk and the opportunity for harm. However, risk and harm are reduced not only by expectations, but also by understanding how using SNSs can impact autonomy and independence.

Respect for Participant Autonomy and Independence

Teachers may find themselves in situations where they are directed to engage with SNSs, such as when a school leader suggests that teachers can add a Twitter post about their weekly classroom events. When this occurs, teachers may feel obligated to use social media even if they do not feel comfortable with the digital tool. Alberta Education’s Learning and Technology Policy Framework (2013), Policy Direction 3 indicates that teachers are expected to “engage in professional growth opportunities that are broadened and diversified through technology, social media, and communities of practice” (Section 3, para. 1). Although some teachers may struggle to give up autonomy over their professional learning choices, they may still have control over what technologies they use or how they use them. The student-centred goal, is that “teachers . . . develop, maintain, and apply the knowledge, skills, and attributes that enable them to use technology effectively, efficiently, and innovatively in support of learning and teaching” (Alberta Education, 2013, Section 3, para 1). Teachers need to consider the magnitude of this responsibility when they do engage with SNSs, as they are in a position in which they can create and shape their own online persona, while also shaping and influencing the identity of their students. In this final section, we will expand on the ethical examination of the teacher’s role in shaping identity and equity of access.

(Re)Shaping Identity

When teachers use SNSs in their classroom, their motivation may be to build relationships, provide support, reduce the feeling of being isolated (for both student and teacher), build personal and professional learning environments, and to create and share knowledge (Forbes, 2018). SNSs are not limited to these opportunities and may provide other features and abilities, such as ‘going live’ to show parents the events in the classroom; however, the fact that teachers and students have the ability to use these features does not necessarily mean that they should.

As previously discussed, teachers and students who engage with SNSs may blur the lines between private and public identity. What teachers should consider is that as they post content such as pictures, student work, or discussions about what happened within the class, they create a digital footprint for themselves, as well as for their students, which may be accessed and retrieved by others (Auld & Henderson, 2014). As teachers move to a more digital learning environment, K-12 teachers are faced with the reality that their digital interactions influence identity, regardless of whether they take place on a private or public SNS account. Forbes (2018) eloquently points out that “what an individual does with social media does not occur in a vacuum and is likely to affect or influence others by virtue of the social character of the communications” (p.178). As teachers consider this influence, they are held ethically to the principle of responsible care, “where professionalism entails doing good and minimizing harm” (Forbes, 2018, p.178).

To build on this idea of doing good and minimizing harm, teachers should consider the power of their influence. By modelling positive digital citizenship and literacy skills, they can inadvertently shape their own and students’ identities in a positive way. One example is practicing proper citations and copyright practices. As Auld and Henderson (2014) point out, the use of a picture of a celebrity or cartoon picture to create a social media avatar may seem harmless, but it is a breach of copyright and possible identity theft. This is an opportunity for a teachable moment that may have lasting effects on students’ identities and on the identity of the original subject whose image was used.

Teachers’ ability to model and shape identity is not just proximal. Auld and Henderson (2014) explain that “teachers can model how to respect the other even if they are not known to the students or the teacher” (p. 202). This removal of barriers is powerful, but the strength is limited by the opportunity for digital equity of access.

Equity of Access

Digital access and equity involve many components and ethical considerations that teachers should consider as they use SNSs. Rooted in social justice, there is a belief that emerging technologies, such as social media, will “level the playing field, effectively creating equal access to learning opportunities by democratizing information and instruction” (Bulger, 2016, p. 2). This is supported by the fact that creating an account on SNSs is most often free. As well, SNSs are ubiquitous communication platforms where, because they are digital, users can access assistive technologies such as speech to text, text to speech, and translation to participate in the discussion. By integrating SNSs in the classroom, teachers provide opportunities for all students to develop their online communication skills, not just the students who can afford to access the platforms from home (Howard, 2013).

The argument that SNSs are free is limited to the actual cost to participate on the site. In order to access SNSs, one needs technology and internet access in the first place. As well, parents may not want their children, or themselves, to communicate online. In order to respect the autonomy of parents and students, teachers may want to consider providing alternatives to online communication. By doing so, teachers follow the social justice principle of recognitive, which, as Lambert (2018) points out, involves recognition and respect for diverse views and experiences.

As teachers use SNSs for communication, their reach of influence is not limited to just their own identity, but beyond. In fact, the impact on identity is a community approach involving (but not limited to) teachers, parents, and students. To maintain the educational integrity that teachers are responsible for, teachers should also consider opportunities for autonomy when involving technology-based practices in their classrooms. By allowing for voice and choice by parents and students, teachers can continue, with effective communication, to build the sense of community that is needed (White, 2016), which was the goal in the first place.

Conclusion

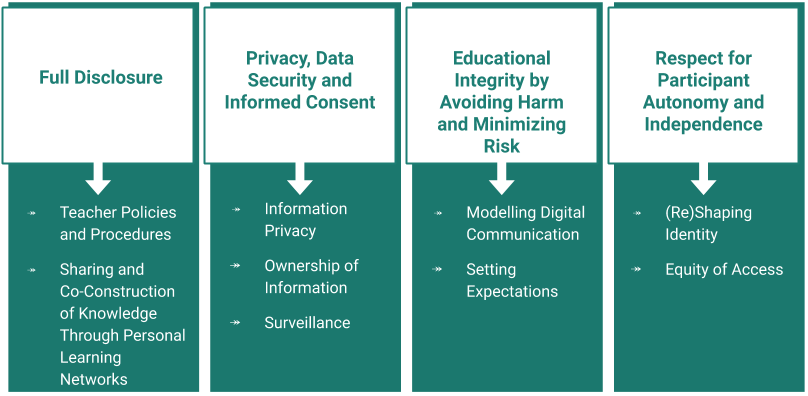

As teachers decide to integrate SNSs into their classroom practices, they should consider the ethical implications that this type of technological opportunity creates. According to Auld and Henderson (2014), “a professional SNS profile is a potentially valuable strategy but it still requires considerable thought and considerable maintenance” (p. 199). By focusing on four main areas of ethical exploration, this chapter examined the topics of full disclosure, privacy and security, educational integrity, and autonomy and independence, in order to address how teachers can tackle the complexity and unique opportunities of using SNSs to communicate in their classroom.

No matter the tool, teachers should consider the magnitude of their responsibility when they do engage with SNS for communication. Part of the attraction of SNSs is the unique abilities to enhance communication, but one may want to have the mantra: just because you have the ability, doesn’t mean you should use it. By continually reflecting on the goal and ethical implications, teachers will have a strong foundation for the use of SNSs for communication.

Questions to Consider for Future Research

- Technology is always evolving, and with it, a teacher’s practice should evolve, too. COVID-19 has required teachers across the globe to move their classrooms to an online environment. Teachers who had never considered SNSs as a way to communicate are now adapting these platforms to fit their classroom needs. What impact will this mass uptake of using SNSs have on pedagogy?

- In what ways are teachers and students reshaping the role SNSs have in education?

- What ethical considerations should be considered when students who are under the age of consent use technology to support their learning?

- Lastly, as teachers model different competencies in their classroom, there are opportunities to embed digital literacies and citizenship while creating opportunities to develop PLNs online. What do students have to gain or lose by participating in a PLN via SNSs?

- What frameworks could teachers consider to scaffold students developing their own PLNs using SNS (refer to Appendix A)?

References

Alberta Education. (2013). Learning and technology policy framework. https://education.alberta.ca/media/1045/ltpf-quick-guide-web.pdf

Alberta Education. (2018). Teaching quality standard. https://education.alberta.ca/media/3739620/standardsdoc-tqs-_fa-web-2018-01-17.pdf

Alberta Teachers Association. (1999, March 30). What you should know about the FOIP Act. ATA News. https://www.teachers.ab.ca/News%20Room/ata%20news/Volume%2033/Number%2015/In%20the%20News/Pages/What%20you%20should%20know%20about%20the%20FOIP%20Act.aspx

Alberta Teachers Association. (2018). ATA code of professional conduct. https://www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Teachers-as-Professionals/IM-4E%20Code%20of%20Professional%20Conduct.pdf

Auld, G., & Henderson, M. (2014) The ethical dilemmas of social networking sites in classroom contexts. In G. Mallia (Ed.), The Social Classroom: Integrating Social Network Use in Education (pp. 192-207). Ringgold Inc. http://ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/docview/1494511269?accountid=9838

Barnes, S. B. (2006). A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States. First Monday, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v11i9.1394

Bulger, M. (2016). Personalized learning: The conversations we’re not having. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/pubs/ecl/PersonalizedLearning_primer_2016.pdf

Couros, G. (2012, November 18). Personal and professional vs. public and private. George Couros. https://georgecouros.ca/blog/archives/3432

Dienlin, T., & Trepte, S. (2015). Is the privacy paradox a relic of the past? An in‐depth analysis of privacy attitudes and privacy behaviors. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(3), 285– 297. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2049

Elk Island Catholic Schools. (2019, September). Social media. Administrative Procedure 146. https://www.eics.ab.ca/download/218652

Facebook. (2019, July 31). Terms of service. https://www.facebook.com/terms.php

Farrow, R. (2016). A framework for the ethics of open education. Open Praxis, 8(2), 93-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.2.291

Forbes, D. (2017). Professional online presence and learning networks: Educating for ethical use of social media. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7), 175-190. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.2826

Henderson, M., Auld, G., & Johnson, N. F. (2014, September 30-October 3). Ethics of teaching with social media [Paper presentation]. Australian Computers in Education Conference 2014, Adelaide, SA. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.719.2437&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Howard, K. E. (2013). Using Facebook and other SNSs in k-12 classrooms: Ethical considerations for safe social networking. Issues in Teacher Education, 22(2), 39-54. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/education_articles/50/

International Council on Human Rights Policy. (2011). Navigating the dataverse: Privacy, technology, human rights. http://www.ichrp.org/files/reports/64/132_report_en.pdf

Law Now. (2019, September 3). In loco parentis. https://www.lawnow.org/in-loco-parentis/

Molnar, A., & Boninger, F. (2015). On the block: Student data and privacy in the digital age. National Education Policy Center. http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/schoolhouse-commercialism-2014.

Nias, J. (1999). Primary teaching as a culture of care. In J. Prosser (Ed.), School culture (pp. 66-81). SAGE Publications Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446219362.n5

Oxford University Press (OUP). (2019). Disclosure: definition of disclosure. https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/disclosure

Planbook. (n.d.). Digital ethics: Responsible social media practices for educators. https://blog.planbook.com/digital-ethics/

Regan, P., & Jesse, J. (2019). Ethical challenges of edtech, big data and personalized learning: Twenty-first century student sorting and tracking. Ethics and Information Technology, 21(3), 167-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-018-9492-2

Roberts, V. (2019). Open educational practices (OEP): Design-based research on expanded high school learning environments, spaces, and experiences [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Calgary.

Sideri, M., Kitsiou, A., Kalloniatis, C., Tzortzaki, E., & Gritzalis, S. (2017). “I have learned that I must think twice before…”. An educational intervention for enhancing students’ privacy awareness on Facebook. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 792, 79-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71117-1_6

Velestianos, G. (Ed.). (2016). Emergence and innovation in digital learning: Foundations and applications. AU Press, Athabasca University. https://doi.org/10.15215/aupress/9781771991490.01

White, K. W. (2016). Teacher communication: A guide to relational, organizational, and classroom communication. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca

Appendix A

| Teacher-Led Walled Garden of Open Learning | Transition Between Teacher-Led Walled Garden & Independent Open Learning | Developing Personal Learning Networks |

|---|---|---|

| Up to age 11

AND/OR. Emerging open readiness learners |

Ages 11-14

AND/OR. Low & medium open readiness learners |

Ages 14+

AND/OR. High open readiness learners |

| Example: Teacher connects with their PLN to share classroom learning experience using classroom social media identity. | Example: Teacher co-designs for learning pathway that includes inside/outside experts & open/closed sharing of learning experiences. | Example: Teacher co-designs for learning pathway that encourages inside/outside classroom experts, nodes of learning, & perspectives in order to solve problem with choice open/closed sharing of learning. |

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.1 Six components of culture of care, adapted from Nias (1999) © Heather van Struen is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 2.2 Attitudes to limit exposure of privacy, adapted from Regan and Jesse (2019) © Heather van Struen is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- fig8_struen