Chapter 9: To What Extent Does Fake News Influence Our Ability to Communicate in Learning Organizations?

Dean Parthenis

The proliferation of fake news has seen rapid growth in its ability to spread quickly due to the access to, and convenience and ease of, digital technology that provides users with the option to share and receive instantaneous communications to and from millions of people globally. This process lends itself to many ethical challenges for all of the end users of digital technology and various platforms. It also has impact within educational, professional, and personal contexts. Due to limitations, my chapter will only focus on selected aspects of fake news relevant to education, such as understanding and identifying it, the role technology and citizens can play in the distribution of mistruths, AI detection tools, and taking steps to better navigate and protect against fake news.

The quickest way of spreading fake news is via social media channels. The most popular media include — but are not limited to — Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, WeChat, Tumblr, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Reddit, and YouTube. Recent research confirms just how quickly misinformation can spread among an information-hungry society. Aside from social media, many people use search engines (Google, Yahoo, or Bing) or depend on various mainstream news media, left- or right-wing websites, or community journalists to receive information. The sheer volume, immediacy, and combination of information sources only adds fuel to the fire by blasting out false news at unprecedented speeds. According to Rheingold (2012), “the average American consumes thirty-four gigabytes of information on an average day” (p. 99).

Defining what fake news is and identifying potential implications of the increase in fake news will help to provide a base-level understanding of the current situation. However, we must also understand that there are tools and techniques one can use to detect fake news, protect oneself, and avoid making the situation worse by spreading it. By examining the impact of fake news on the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak, we can gain some insights into how this information phenomenon has become what I refer to as a “digital information virus” and what others — such as the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) — refer to as an infodemic. Conversely, to counter fake news and help to create a factual, credible, and timely source of information, I will provide a snapshot of my overall experience in risk and crisis communications, including the messaging process that helped to keep key audiences accurately informed at an Alberta based post-secondary institution at the point and time of this writing.

Ultimately, fake news causes a chain reaction effect in society, and this has several ethical implications that may result in unexpected potential outcomes. Based on my real-time and participatory emergency and pandemic-related communications experiences, I will suggest an easy-to-use matrix tool to help people detect fake news and offer a new strategic communications approach for organizations to establish consistent and credible sources of information that will help to offset fake news and prevent it from spreading.

What is Fake News?

It is important to gain a basic understanding of what fake news is and how it is distributed. While the definitions may vary, fake news is essentially information that is not true and is intended to misguide, fool, provide mistruths, or deceive people into believing the stated falsehood(s) (Charlton, 2019; Dulhanty et al., 2019; Watters, 2017). Other terms used to refer to fake news that have been used in public forums include: hoax, misinformation, and disinformation. Additionally, Collins Dictionary labelled “fake news” the word of the year in 2017. Rheingold (2012) suggests that performing more than one search query and going beyond the initial search page results can reduce the chances of getting fooled by fake news. While it may seem as though fake news is a more recent informational phenomenon — most notably during the 2016 presidential election campaign in the United States — this is not actually the case. According to Heidi Tworek (2019), a historian and author from the University of British Columbia, disinformation likely had its origins in the 16th century with the establishment of the printing press and early newspapers. She explains that the earliest form of fake news came from groups who spread anti-Semitic information about Jewish people.

Fast forward to the present day, and we find ourselves thrust into a seemingly endless stream of information flowing through social media channels, the traditional news media and other rogue and less than credible sources. To gain a greater sense of the severity of the problem on a global scale, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and the United Nations Human Rights Commission issued a Joint Declaration on freedom of expression, focusing on fake news, disinformation, and propaganda (OSCE, 2017). But it is the public’s insatiable appetite for information and the ease in which it can be shared, viewed, and liked via the use of various forms of technology that makes it even more difficult to discern fake news from credible and reliable information and news.

Is Technology to Blame?

While there has been a rapid evolution in the type of communication-related technology that can be used by consumers, we have to remember that someone is responsible for preparing the message. According to Cybenko and Cybenko (2018), the current state of technology and social media helps fake news thrive in a so-called ‘petri dish’. Another expert suggests a direct linkage between fake news and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Samuel Woolley (as cited in Powers & Kounalakis, 2017) states that “security experts argue that more than 10 percent of content across social media websites and 62 percent of all web traffic is generated by bots — pieces of computer code that automate human tasks online” (p. 19).

Conversely, a study from MIT shows that humans are the key culprits when it comes to releasing fake or misleading information. Using the process on Twitter as an example, Vosoushi et al. (2018) surmise that a cascading effect occurs when information is posted (tweeted). “A rumour cascade begins on Twitter when a user makes an assertion about a topic in a tweet, which could include written text, photos, or links to articles online” (p.1). Furthermore, the authors’ key findings reveal that false news stories are more likely to be retweeted seven out of 10 times compared to true stories. To make matters worse, it has become extremely easy to send messages and spread mistruths via the use of smartphones, among other digital devices (such as tablets).

Coronavirus ‘Infodemic’

The COVID-19 (coronavirus) worldwide pandemic is a great example of how difficult it has been for health organizations not only to help prevent the spread of the virus to humans, but also to manage the rapid explosion of disinformation, which can exacerbate the situation. The World Health Organization (2020) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. The spread of misinformation can cause unnecessary panic. Here is a brief summary of examples that were uncovered by the BBC News Reality Check team (2020) in relation to misinformation in Africa:

- Dettol can be used to protect against coronavirus. An image of a bottle of the disinfectant (Dettol) was shared on social media, and it was implied that it could prevent the spread of COVID-19. This statement was FALSE.

- Shaving a beard can protect against coronavirus. An old graphic from US health authorities about facial hair was incorrectly used to suggest shaving beards would help men avoid contracting the virus. It was even attributed to the CDC. This statement was FALSE.

- A preacher posted a video claiming that pepper soup could cure coronavirus. This information quickly spread after being shared on WhatsApp. This statement was FALSE.

These fake news items, along with numerous others, caused the World Health Organization to state that the outbreak has caused not only an epidemic but an infodemic of false and misleading information. The goal is to ensure everyone has accurate information to help prevent the spread of the disease (Zaracosta, 2020). Tech giants, such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter are leading the fight to mitigate mistruths on the Internet. But as Holmes (2020) suggests, “the bigger threat is speculation and false rumours about coronavirus that spread organically on online forums” (para. 4). The nature of this threat is primarily due to the speed at which news can travel. To make matters worse, the spread of false information during COVID-19 has been exacerbated by a few world leaders, including Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro (Garcia & Benitacanova, 2020) and most notably US President Donald Trump when he falsely touted chloroquine as a drug that could treat COVID-19 (Liptak & Klein, 2020).

Detecting and Protecting Against Tall Tales

The first step towards protecting oneself against disinformation is to know what to look for in order to sort fact from fiction. This can be a daunting task; however, there are some basic questions one can ask and tools one can use to help make the detection process easier. Rheingold (2012) suggests learning key skills like “learning attention and crap-detection skills” (p. 114). There are also several fact-checking organizations that people can utilize including Snopes, Politifact, and the Media/Bias Fact Check website, which is made up of a team of fact-checkers who review and assess the accuracy and biases of dozens of news sites.

University of Waterloo researchers recently developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool to help social media networks and news organizations flag fake stories (2019). Based on what the researchers call “deep-learning AI algorithms, they can scan thousands of social media posts and news stories and make relevant links to other sources of information” (Dulhanty et al., 2019). Similarly, researchers at MIT developed a new system that uses technology (machine learning) to determine if a source is accurate or politically biased (Baly et al., 2018).

Some news organizations are providing their viewers and listeners with key fact-checking advice. CBC News has developed a chatbot tool for Facebook messenger. This tool is accessible online and provides users with several weeks of “learning about misinformation and disinformation, from deep fakes to suspicious articles” (CBCb, 2019, Image caption section).

Rheingold (2012) suggests asking a key question when viewing or watching information updates: “once you’ve searched, you need to determine how much you should trust the info your search has yielded” (p. 89). CBC (2019a) suggests asking key questions such as:

- Are the details of the story thin or unavailable?

- Does the story seem too bad or too good to be true?

- Have I heard of this organization before?

- Can I find another source that confirms and counters this information? (How do I know if it’s disinformation? section)

Within educational circles, there is a growing effort to provide relevant learning resources to students to fight the spread of fake news within Canada, such as mediasmarts.ca. In the US, the Digital Literacy Resource Centre (DRC) has provided key learning opportunities for students and staff online (Jackobson, 2017). According to Manzini (2015), digital platforms provide enabling solutions for organizations (p. 168), and students can certainly broaden their learning opportunities under the right set of circumstances and safety considerations. There is certainly an opportunity to develop more consistent educational resources for students and teachers in Canada for K-12 and post-secondary institutions.

Risk and Crisis Communications

With over 20 years of experience in risk and crisis communications, including as a sessional instructor in continuing education at a post-secondary institution, I realize the importance of audiences receiving timely and factual information from credible sources. The act of disinformation could have reputational health and safety ramifications for end-users and receivers of information. Regan and Jesse (2018) advise that there are a range of ethical issues that should be considered in regards to the use of edtech and data. To help add some further context to this area of communications within the realm of fake news, it is important to delineate the differences between risk communications and crisis communications.

The process of risk communications deals with things that might go wrong (Telg, 2019). According to Fearn-Banks (2017), it is an ongoing program of informing and educating various publics (usually external publics) about issues that can negatively or positively affect an organization’s success. Based on my work experience, relationships between an organization and its key publics need to be established before a situation escalates into a crisis.

The process of crisis communications deals with things that do go wrong (Telg, 2019). Crisis communications is the dialogue between the organization and its public(s) prior to, during, and after the negative occurrence (Fearn-Banks, 2017). Effective communications consist of preparing a crisis communications plan with supporting tactics, of involving the team in training scenarios to help mitigate any reputational harm against the organization, and of being strategic in enacting the crisis communications plan.

Experience and Strategic Audience Engagement

As a former media relations manager, trainer, and spokesperson for an Alberta-based police service (1999-2011), I was involved in disseminating daily, accurate information to internal audiences and the public through various digital platform technologies including news, social media, and organizational communication channels (email, website, Intranet, conference calls, news conferences, so on), which helped to contribute to the overall well-being, education, and safety of citizens, and employees. Any mistruths would have a negative effect on how seriously people would take any information they received from police. This could also impact the effectiveness of educational school programs such as the D.A.R.E. program.

It is not unusual for fake news to escalate during a time of crisis. During the flood of 2013 in a southern Alberta city, I was employed as a Public Affairs Manager, and I noted that disinformation would flare up and hinder efforts to have the public follow safety instructions. Our approach was to correct and address any mistruths as soon as possible to prevent their further spread. Some disinformation was centred on the actual importance of having a 72-hour emergency preparedness kit. Some fake information resulted in people doubting its importance, leaving them vulnerable to not being properly prepared to survive the situation. Any type of mistruth only serves to work against emergency services personnel, who only have the health and safety of the public in mind.

A more recent example is based on my participatory role and perspective regarding the communications process at a post-secondary institution during the COVID-19 outbreak from the period of January-March 31, 2020. As the senior manager of media and issues management, I led an effort to establish the trusted communications channels to share relevant and timely informational updates with the campus community and to help prevent the spread of disinformation. I prepared a communications plan with tactics and specific communications drafted in conjunction with executives and teammates in various departments during the early risk communications phase and in advance of COVID-19 being declared a pandemic by the WHO. The plan was fluid and adaptable to audience needs as the outbreak became a crisis; this included the creation of a central hub of factual information and relevant links by colleagues (a COVID-19 themed website). To help mitigate fake news, an institution needs to provide strong and consistent internal and external communications, including the news media.

In this digital age, the use of social media has also amplified the amount of information being shared in general during the worldwide pandemic. Dr. Peter Chow-White aptly described its impact in the Saanich News: “social contagion operates very similarly to viral contagion; there is a network effect, and social media amplifies this” (Mclachlan, 2020). Additionally, Powers & Kounalakis (2017) support research findings that indicate people are actually relying on digital platforms like Twitter and Facebook for their news. This increases the “level of exposure they have to a multitude of sources and stories” (p. 4). More importantly, Rheingold (2012) suggests that people need to learn how to participate effectively online to help reduce the spread of disinformation.

Tips to Detect Fake News

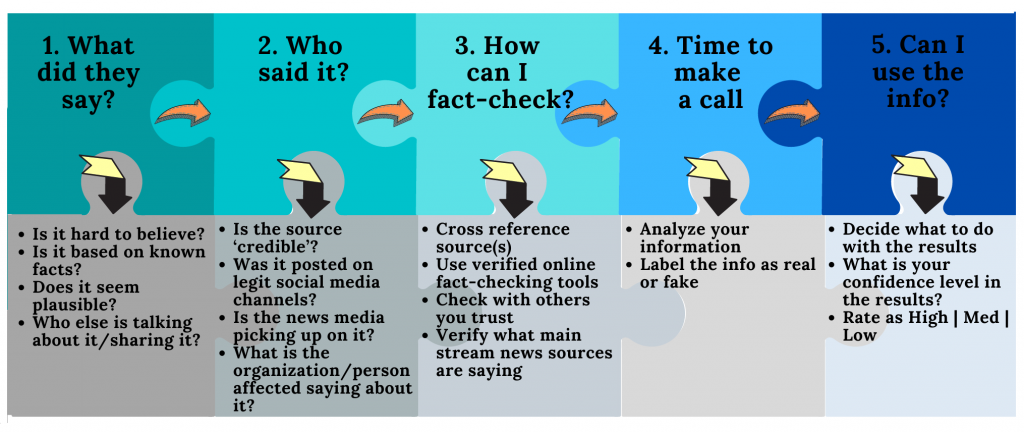

My own experience and research suggest a solution to help safeguard and protect against fake news. I have developed a simple process to verify the information one encounters via social media and news media circles (Figure 9.1).

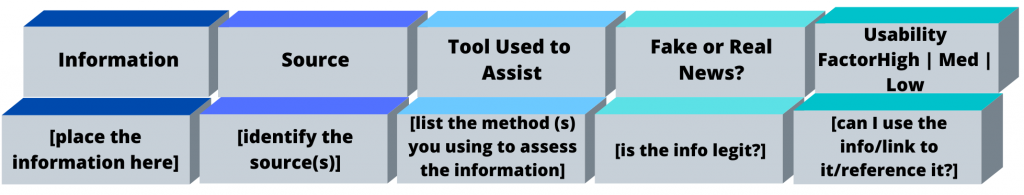

Individuals can also create an easy-to-follow chart based on the above themes in a word document, PDF or Excel format. This information is meant to help guide people as they identify, track and assess fake news.

Effective Communications Process During a Pandemic

Equally important for organizations and professional communicators is to have a strategy in place prior to and during a time of crisis to provide a source of credible information and to also protect against disinformation. This new eight-step model is informed by action research, my personal industry experience, digital technology, creativity, design principles, and best practices. This process can help to offer guidance during the planning process (risk and crisis situations).

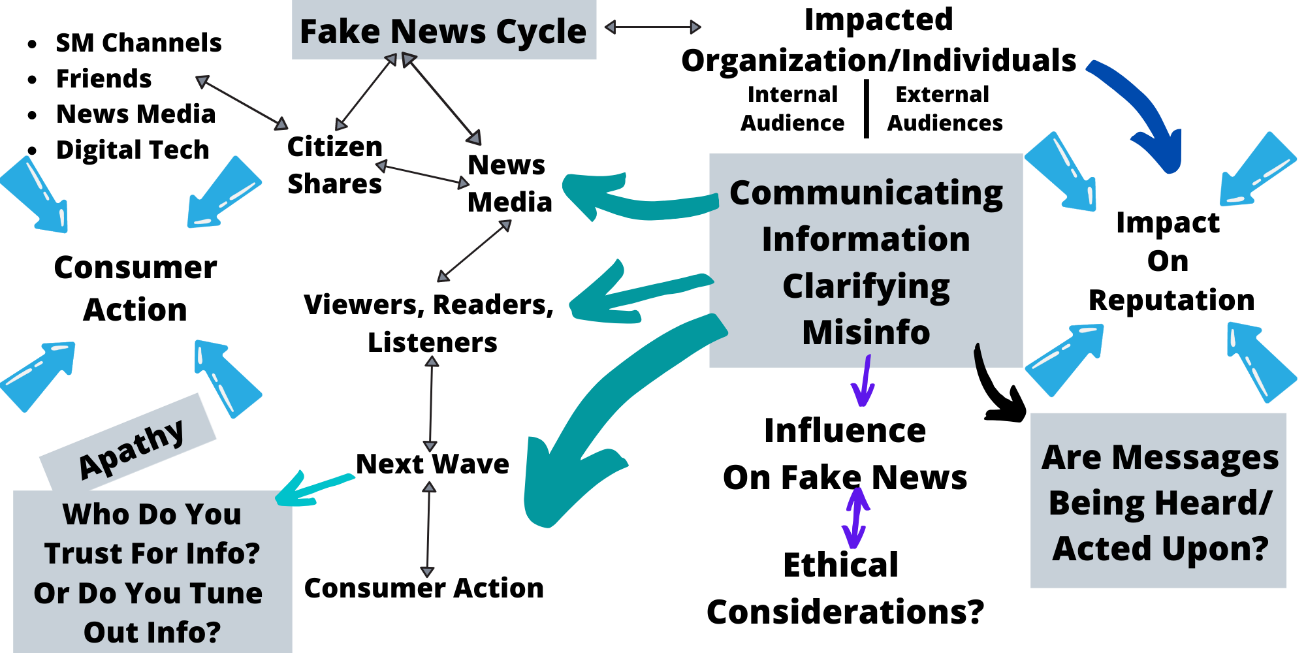

Ethical Considerations

From a broader perspective, the onus of responsibility in mitigating the proliferation of fake news requires a complementary effort by a variety of end-users of technology. A study conducted by Gabielkov et al. (2016) reveals that many people share links on Twitter without reading the information first: “out of 10 articles mentioned on Twitter, 6 typically on niche topics are never clicked” (p. 8). This influences what information gets circulated. Moreover, in 2017, the news site The Science Post published a block of “lorem ipsum” text. According to Dewey (2017), “nearly 46,000 people shared the post without reading past the headline.” This is a concerning trend, as the speed at which people can now create and distribute information globally is unprecedented. The chain reaction cause and effect of fake news as depicted in Figure 9.4 is far-reaching.

A closer analysis of the ‘typical’ key players involved in creating and sharing information highlights the ethical challenges for these groups. In table 9.1 , ethical highways for consideration, are based on Farrow’s normative theory (2016).

| Group | Influencer or Impacted | Normative Theory |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

Impact on Education

There are many positive societal implications associated with widespread access to and use of digital technology and platforms. However, some individuals cross the line with their messaging, and, as a result, fake news can go viral very quickly. These actions have impactful ramifications on education — especially for knowledge-seekers scouring online for references and various learning resources. Educators, organizations, and journalists, among others, have a common desire to inform and educate, and to provide factual and helpful information on a variety of topics. One researcher has signified the importance of this, while also recognizing the associated ethical challenges. In his article A Framework for the Ethics of Open Education, Farrow (2016) offers the following insight: “as openness increasingly enters the mainstream, there is concern that the more radical ethical aspirations of the open movement are becoming secondary” (p. 94).

Action research provides the opportunity to link theory and practice. In my experience, utilizing this approach to prepare a risk/crisis communications plan is more effective than using the ‘traditional’ public relations method. The key research steps of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting (McNiff, 2014) offers a pragmatic yet theoretically based and informed approach to strategic preparations. Moreover, when innovating possible solutions, it is equally important to incorporate a design thinking process such as Ostrom’s design principles (Rheingold, 2012) in a way that is also applicable and relevant in real-world contexts (Kelly, 2016). The constant cycling method of action research provides regular opportunities to help finetune even the most complex business practices.

Moreover, adopting a relatively new mindset in the field of crisis communications, namely “creative readiness” (Fichet, 2018), was also beneficial to me as a professional communicator. Fichet (2018) describes this approach as “improvising in acute situations based on creativity and earlier experiences” (p.34). The ability to respond more creatively as a particular crisis unfolds is a helpful strategy and can provide another way to mitigate falsehoods and to protect an organization’s reputation.

Rheingold (2012) reminds us that when we are navigating in the digital world, the onus of being responsible and ethical end users is something we should not take for granted. Everything we write, say, or do via social media platforms quickly becomes a part of the bigger picture: “if you tag, favourite, comment, Wiki edit, curate or blog, you are already part of the web’s collective intelligence” (Rheingold, 2012, p. 148). But unfortunately, presently, and in the amount of time it takes to ‘post’ or hit ‘send,’ most people are already being negatively impacted by falsehoods being presented as facts.

Herein lies the importance of being able to appropriately detect fact from fiction when it comes to what we hear or view on the news or via social media circles. A proliferation of mistruths online will only serve to cast doubt on the credibility of information available to learners from K-12 to post-secondary, potentially resulting in a host of other issues. Regan & Jesse (2018) raise the importance of addressing ethical issues initiated by a spike in the use of edtech and big data in school systems. There is certainly a need for more research in this area, as we still have much to learn. The big question moving forward is what else can we do to more effectively navigate and protect ourselves against fake news while reaping the learning benefits of digital technology in our ever-evolving digital climate?

References

Baly, R., Karadzhov, G., Alexandrov, D., Glass, J., & Nakov, P. (2018). Predicting factuality of reporting and bias of news media sources [Conference session]. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium. https://www.doi.org/10.18653/v1/D18-1389

CBC News. (2019a, July 5). So, you think you’ve spotted some ‘fake news’ — now what. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/fake-news-disinformation-propaganda-internet-1.5196964

Charlton, E. (2019, March 6). Fake news: What it is, and how to spot it. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/fake-news-what-it-is-and-how-to-spot-it/

Cybenko, A. K., & Cybenko, G. (2018). AI and fake news. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 33(5), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1109/mis.2018.2877280

Dewey, C. (2016, June 17). 6 in 10 of you will share this link without reading it. NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/offbeat/6-in-10-of-you-will-share-this-link-without-reading-it-a-new-depressing-study-says-1420091

Dulhanty, C., Deglint, J. L., Daya, I. B., & Wong, A., (2019, November 27). Taking a stance on fake news: Towards automatic disinformation assessment via deep bidirectional transformer language models for stance detection [Conference session]. AI for Social Good Workshop at NeurIPS 2019. https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.11951

Farrow, R. (2016). A framework for the ethics of open education. Open Praxis, 8(2), 93-109. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.2.291

Fearn-Banks, K. (2016). Crisis communications: A casebook approach. Taylor & Francis Group.

Fichet, E. S. (2018). Creativity readiness in crisis communications: How crisis communicators’ ability to be creative is impacted at the individual, work team, and organizational levels (Publication No. 10831554) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Gabielkov, M., Ramachandran, A., Chaintreau, A., & Legout, A. (2016). Social clicks: What and who gets read on Twitter?. ACM SIGMETRICS Performance Evaluation Review, 44(1), 179-192. https://doi.org/10.1145/2964791.2901462

Garcia, R.T, (2020, March 20). As Brazil confronts coronavirus, Bolsonaro and his supporters peddle fake news. Quillette. https://quillette.com/2020/03/20/as-brazil-confronts-coronavirus-bolsonaro-and-his-supporters-peddle-fake-news/

Holmes, A. (2020, March 10). A coronavirus fake news ‘infodemic’ is spreading online faster than tech companies’ ability to quash it. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/tech-companies-and-governments-are-fighting-coronavirus-fake-news-2020-3

Jacobson, L. (2017, October 24). Schools fight spread of ‘fake news’ through news literacy lessons. K-12 Dive. https://www.educationdive.com/news/schools-fight-spread-of-fake-news-through-news-literacy-lessons/507057/

Kelly, R. W. (2016). Creative development: Transforming education through design thinking, innovation, and invention. Brush Education Inc.

Manzini, E. (2015). Design, when everybody designs: An introduction to design for social innovation. MIT Press.

McLauchlan, P., & Wadhwani, A. (2020, March 29). Social media a blessing and a curse during time of crisis. Cloverdale Reporter. https://www.cloverdalereporter.com/news/social-media-a-blessing-and-a-curse-during-time-of-crisis-b-c-communication-expert/

McNiff, J. (2014). Writing and doing action research. Sage Publications Ltd.

Media Bias Facts Check. (n.d). Search and learn the bias of news media. https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. (2017). Joint declaration on freedom of expression and “fake news”, disinformation and propaganda. OSCE. https://www.osce.org/fom/302796

Regan, P. M., & Jesse, J. (2018). Ethical challenges of edtech, big data and personalized learning: Twenty-first century student sorting and tracking. Ethics and Information Technology, 21(3), 167-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-018-9492-2

Rheingold, H. (2012). Crap detection 101: How to find what you need to know, and decide if it’s true. In Net Smart: How to Thrive Online (pp. 77-111). MIT Press. https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/servlet/opac?bknumber=6757883

Reality Check Team. (2020, March 13). Coronavirus: What misinformation has spread in Africa? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-51710617

Telg, R. (2018). Risk and crisis communication: When things go wrong. University of Florida IFAS Extension. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/wc093

Tworek, H. (2019). News from Germany: The competition to control world communications, 1900–1945. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvckq588

University of Waterloo. (2019, December 16). New tool uses AI to flag fake news for media fact-checkers. ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/12/191216122422.htm

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https//doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Watters, A. (2017). Education technology and ‘fake news’. Hacker Education. http://hackeducation.com/2017/12/02/top-ed-tech-trends-fake-news

World Health Organization. (2020). Managing the COVID-19 infodemic: Call for action. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010314

Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. The Lancet, 395(10225), 676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X

Media Attributions

- Figure 9.1 Five-step source assessment process for fake news © Dean Parthenis is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 9.2 Source assessment matrix tool © Dean Parthenis is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 9.3 Eight-step communications process for risk and crisis situations © Dean Parthenis is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 9.4 Chain reaction cause and effect of fake news © Dean Parthenis is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license