4.2 Misinformation Today: The Media

Sarah Gibbs

Media Fracturing & Iterative Journalism

These days, we can choose our news.

In the past, sources of information were limited. If we wanted to find out about a new policy the government was enacting, we could read about it in the newspaper, listen to a report on the radio, or watch the news on TV. There were comparatively few newspapers, radio stations, or TV programs to choose from, and they all reported fairly similar information. Now, the options can appear limitless and news sources often disagree on basic questions of fact.

Our contemporary media environment is characterized by three important features:

- Personal Preference & Source Heterogeneity—Something is “heterogeneous” when it is composed of diverse and / or dissimilar parts. The vast array of media outlets available today means that our media environment is highly heterogeneous. Librarian Nicole A. Cooke (2018) describes the result of a broad array of choices in news outlets:

With a simple click of the mouse, change of the channel, or file download, consumers can choose a news media outlet that is most aligned with their ideological preferences. This is fragmentation in news. It provides more choice and possible exposure to wider perspectives in the news, though at the cost of a radical increase in the amount of biased or unbalanced reports propagating in the mass media.” (p. 13)

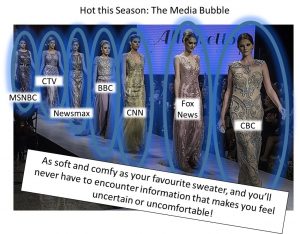

The need for online news sources to drive traffic to their sites in order to generate ad revenue, and their ability to act as “micro media” (p. 13) targeting a highly specific group of consumers, means that these sources tend to simply “give people what they want,” framing and manipulating news stories in ways that appeal to their users. Many people remain entirely within their “media bubbles” and never seek out information from sources with different perspectives or political orientations. Being informed means gathering information from a variety of reputable sources.

- Disintermediation—Essentially, the removal of intermediaries. Internet platforms greatly reduce or completely eliminate barriers for publishing “citizen-produced content” (Cooke, 2018, p. 13). New online media pathways bypass traditional “information gatekeepers,” like professional journalists and fact-checkers. Cooke (2018) notes, “Disintermediation is yet another reason why fake news thrives, because information can travel from content producer to consumer in a matter of seconds without being vetted by intermediaries such as reputable news organizations” (p. 13-14).

- Iterative Journalism—Iterative journalism is the practice whereby “media personalities […] report[…] what they’ve heard, not what they have discovered or sought out directly” (Cooke, 2018, p. 12). Basically, it’s when news outlets report information second-hand. The contemporary twenty-four-hour news cycle means that media sites are under incredible pressure to provide a continual stream of new information; as a result, they are often re-reporting stories they’ve found elsewhere on the web. The situation is a recipe for propagation of misinformation, disinformation, and fake news. Fallacious stories can enter the media “food chain” on local news blogs or sites that carry out little-to-no fact checking, and then work their way up to major media outlets.

“When we open our ideas up to group scrutiny, this affords us the best chance of finding the right answer. And when we are looking for the truth, critical thinking, skepticism, and subjecting our ideas to the scrutiny of others works better than anything else. Yet these days we have the luxury of choosing our own selective interactions. Whatever our political persuasion, we can live in a ‘news silo’ if we care to. […] These days more than ever, we can surround ourselves with people who agree with us. And once we have done this, isn’t there going to be further pressure to trim our opinions to fit the group?”

Lee Mcintyre; Post-Truth (2018)

Novelty Bias

On 22 June 2021, the New York Times newsletter, On Tech with Shira Ovide published some surprising statistics. According to Ovide:

- Americans spend about two-thirds of their TV time watching conventional television and just 6 percent streaming Netflix.

- Online shopping accounts for less than 14 percent of all the stuff that Americans buy.

- Only one in six U.S. employees works remotely.

- About 6 percent of Americans order from the most popular restaurant delivery company in the United States.

One of the reasons that the statistics may be surprising—we’re generally under the impression that everyone streams Netflix and that we all buy everything from Amazon—is, according to Ovide, that “ people (and journalists) tend to pay more attention to what’s new and novel” (2021b, n.p.).

This tendency to report not what is representative of an entire situation or population, but rather what is atypical or interesting, is called “novelty bias,” and it is particularly problematic in the area of science reporting.

Scientific research is a gradual process in which a series of methodologically sound and ethically rigourous studies build toward a generally accepted conclusion. On the way to this state of relative scientific certainty, unusual results and outlier studies will inevitably emerge. Quality science reporting will contextualize single atypical result sets within the context of the research in the area, and make clear that, while the study may be sound, the bulk of the research supports a different conclusion. Unfortunately, media items describing “scientific breakthroughs” do not always provide a balanced view of the discipline. Outlets focused on generating “clicks” and ad revenue may engage instead in selective evidence dissemination and sensationalize the results (O’Connor & Weatherall, 2019, pp. 156). The story is not false, but its information is decontextualized and misleading. Propagandists rely heavily on selective evidence dissemination in order to shape public perception of issues.

“There is a famous aphorism in journalism, often attributed to a nineteenth-century New York Sun editor, either John B. Bogart or Charles A. Dana: ‘If a dog bites a man it is not news, but if a man bites a dog it is.’ The industry takes these as words to live by: we rarely read about the planes that do not crash, the chemicals that do not harm us, the shareholder meetings that are uneventful, or the scientific studies that confirm widely held assumptions.”

Cailin O’Connor & James Owen Weatherall; The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread (2019)

Supplemental Video: Top Four Tips to Spot Bad Science Reporting (https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/c7ab68b7-0f23-4888-952d-127ec9b71c17/top-4-tips-to-spot-bad-science-reporting-above-the-noise/). PBS

The Affective / Emotional Elements of Information

Have you ever been in this situation? Someone presents his or her side of an argument and supports it with evidence you can’t refute, but nonetheless, you still feel that the other side or perspective is true. According to Nicole A. Cooke (2018):

One of the hallmarks of the post-truth era is the fact that consumers will deliberately pass over objective facts in favor of information that agrees with or confirms their existing beliefs, because they are emotionally invested in their current mental schemas or are emotionally attached to the people or organizations [that] the new information portrays. (p. 7)

Our desire for something to be true because we’re emotionally invested in it often leads us to put aside rational thinking and commit to positions we know intellectually are false (Cooke, 2018). The television show The Colbert Report coined the term “truthiness” to describe the phenomenon: it’s not true, but it feels like it is (Cooke, 2018).

Disinformation and fake news often rely on people responding emotionally, rather than rationally, to news items. Taking a step back when you encounter news that makes you angry or afraid and ensuring that the story comes from a reputable source and cites reliable evidence can help you avoid falling prey to the emotional manipulation of online bad actors.

Cognitive Bias

“We are all beholden to our sources of information. But we are especially vulnerable when they tell us exactly what we want to hear.”

Lee Mcintyre; Post-Truth (2018)

Above the Noise. (2017, May 3). Why do our brains love fake news? [Video]. YouTube, https://youtu.be/dNmwvntMF5A.

Check out Lee Mcintyre’s (2018) description of two common manifestations of cognitive bias.

The Backfire Effect

“The ‘backfire effect’ is based on experimental work by Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler, in which they found that when partisans were presented with evidence that one of their politically expedient beliefs was wrong, they would reject the evidence and ‘double down’ on their mistaken belief. Worse, in some cases the presentation of refutatory evidence caused some subjects to increase the strength of their mistaken beliefs. […] Some have described trying to change politically salient mistaken beliefs with factual evidence as ‘trying to use water to fight a grease fire.’ […] / [However], even the strongest partisans will eventually reach a ‘tipping point’ and change their beliefs after they are continually exposed to corrective evidence.” (pp. 48-51)

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

“The Dunning-Kruger effect (sometimes called the ‘too stupid to know they’re stupid’ effect) is a cognitive bias that concerns how low-ability subjects are often unable to recognize their own ineptitude. Remember that, unless one is an expert in everything, we are probably all prone to this effect to one degree or another. […] In their 1999 experiment, David Dunning and Justin Kruger found that experimental subjects tended to vastly overestimate their abilities, even about subjects where they had little to no training. […] In intelligence, humor, and even highly skilled competencies such as logic or chess, subjects tended to grossly overrate their abilities. Why is this? As the authors put it, ‘incompetence robs [people] of their ability to realize it…The skills that engender competence in a particular domain are often the very same skills necessary to evaluate competence in that domain—one’s own or anyone elses’s.’ The result is that many of us simply blunder on, making mistakes and failing to recognize them. […]

[…] Perhaps this is the most shocking thing about the Dunning-Kruger result: the greatest inflation in one’s assessment of one’s own ability comes from the lowest performers.” (pp. 51-53)

The Deep Dive

DANIELE ANASTASION

The New York Times, 30 November 2016

Activity