36 Reflection and Feedback Interaction: ePortfolio Pedagogical Strategies that Help Students Engage with their Learning

Rita Zuba Prokopetz

Educational Consultant and Independent Scholar

ABSTRACT

As demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching in online environments presents significant complexities. Engaging learners and educators in online activities is a challenging endeavour; therefore, educators should focus their course design (and subsequent facilitating) on student learning rather than content uploading and lecturing. Courses that are well designed for hybrid, blended, or in-person learning formats tend to rely on instructional tools that foster student interaction. As pedagogical tools of many purposes, electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) embody attributes that promote awareness, self-assessment, reflection, and feedback interaction. ePortfolios are reflective, demonstrative, and developmental since they foster student engagement in their learning process. Empirical evidence supports the belief that ePortfolios help enhance interaction among students and their instructors. Based on personal experience with language learners, college educators, and graduate students over a decade, it was shown that timely and targeted feedback, albeit time-consuming, was among the pedagogical strategies that helped stimulate project revision and subsequent completion. Moving forward, continuous feedback engendered by general chat systems may lead to a more collaborative form of communication to help engage students further in their learning process. This chapter shares insights and perspectives of a learner and educator based on personal experiences with capstone projects. It demonstrates how courses that include ePortfolio development embrace pedagogical strategies that promote student engagement in their learning. It also suggests possibilities for ePortfolio research studies to leverage the accessibility of AI tools that can assist educators in evaluating the quality of reflective passages and feedback-giving and receiving interactions of their students.

Keywords: ePortfolio, Feedback Interaction, Pedagogy, Reflection, Self-Assessment, Student Engagement

INTRODUCTION

Instruction, in any modality carries a certain level of complexity and requires adaptation to the context, subject matter, and learners themselves (Bates, 2019). Although the teaching occupation is characterized by subtle shades of context-specific principles, “it is possible to provide guidelines or principles based on best practices, theory, and research that must then be adapted or modified to local conditions” (Bates, 2019, p. 60). As the institution of education experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, the sudden shift to distance education proved to be very demanding for all actors involved (Salta, Paschalidou, Tsetseri & Koulougliotis, 2022). Members of the academy globally realized that teaching that occurs “in online courses is an extremely complex and challenging” endeavour (Anderson et al., 2001, p. 3). The initial notion that instructors in traditional settings could continue performing their craft by simply uploading content to virtual spaces has been refuted. As those in the institution of education have learned, the transition from offline to online teaching and learning, although evolutionary in many ways, is very complex (Williamson, 2020, p. 112). Educators and learners, many with little or no experience at all in this new setting, were thrust into teaching and learning entirely at a distance during the COVID-19 pandemic. In consequence, the academy saw the emergence of a “distinctive approach to pedagogy” in distance education that, albeit not really new, became salient (Williamson et al., 2020, p. 108) when the world underwent a tectonic shift in the way we communicate, learn, and teach. It is noteworthy to point out that “the distinction between distance education and technologically supported traditional education [became] blurred with the increased use of technology to facilitate learning in higher education” (Ragan, 1999, para. 1) even before health restrictions dictated our transition to a new learning modality. Courses in distance education – whether synchronous or asynchronous – usually consisted of dialogues among instructors and students and included “course readings, web explorations, exercises, and individual and collaborative projects” (Anderson et al., 2001, p. 5). ePortfolios are examples of both individual and collaborative projects. They promote engagement (with the learning process) and interaction (with peers and instructors) during feedback-giving and feedback-receiving at various stages of the ePortfolio development process. Engaging learners and educators in online activities can be challenging for various reasons, and among them is a feeling of isolation (Croft et al., 2015; Salta et al., 2022) on the part of all actors in the equation. These student-project interactions provide a safe place for peer-peer communication and course engagement, thus minimizing the feeling of isolation. In addition, with the accessibility of language tools that assist with writing and communication, real-time feedback by instructors on ePortfolio pages can be automated to stimulate ongoing revision and improvement by the students (AISOP, 2024). This readily available form of feedback can be an invitation for “students to continuously review their work and improve on it” (AISOP, 2024, para. 3). This chapter argues that courses that are well designed for hybrid, blended, or in-person learning formats tend to rely on instructional tools that foster student interaction. Courses that included reflective online projects like ePortfolios showed the digital resilience of the students – and their instructors – throughout the ePortfolio development process of curating, creating, reflecting, and presenting. There is empirical evidence that supports the belief that ePortfolios help enhance interaction among students and their instructors (Zuba Prokopetz, 2019). ePortfolio pedagogy, which is built as a framework that allows for the organization of learning (Watson et al., 2016), facilitates the type of learning that enables ongoing, anytime, anywhere interaction. This chapter also suggests that with the growing accessibility of AI tools, new possibilities for ePortfolio research studies have emerged. Educators have opportunities to leverage this new technology to facilitate their evaluation of the depth and quality of reflective passages and feedback giving and receiving interactions of their students in the new pedagogical landscape.

CONTEXT OF THE STUDY

After I completed my first ePortfolio (during my graduate studies, 2011-2013), I implemented a similar project in my practice in my role as instructor of English as a second language (ESL). At the time, I viewed ePortfolios as technology-enabled pedagogy, as these online educational projects enabled me to incorporate technology in my course in a meaningful way. As a learner and educator, I was intrigued by this innovation that had become a key part of a digital ecosystem that empowered me to both learn and teach in a reflective way.

As I continued my ongoing quest for knowledge about this education innovation (during my doctoral program 2015-2019), I noticed that my initial views were beginning to evolve. Scholars and researchers were now viewing this innovation as emerging pedagogy in the digital revolution movement (Eynon & Gambino, 2017). As a result, I chose to engage in a form of professional self-development mediated by ePortfolios (Zuba Prokopetz, 2018) to further experience this powerful pedagogy during my episodes of reflective thinking (analysis of my experiences) and metacognitive reasoning (awareness of my cognition). This effective use of ePortfolios relies on a harmonious interplay between purposeful guidance toward learning and achievement of goals (pedagogy) and proper provision of online tools for project development (technology).

ePortfolio Technology in My Practice

During my ongoing studies on ePortfolios, I was also facilitating a course in an adult education certificate program that, at that time, included an ePortfolio. Since I had experienced the technology as both learner and educator (initially with LiveBinders, and then Weebly, and other Web tools), I was able to assist the course participants in their attainment of some of the competencies required for the digital society. As I recall, the introduction of technology (for all assignments) in this course for college educators was very challenging for most participants. Since a two-page ePortfolio project was a course requirement, everyone managed to complete the assignments and present the project successfully on the last day of class. As a result of this experience, these educators became a little less intimidated when they prepared their students to attain essential competencies for the rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICT) – (Benito-Osorio et al., 2013). As educational institutions experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, academic staff faced many challenges in preparing (themselves and their students) for the learning-at-a-distance form of instruction. They also had to overcome barriers related to learning to deal with the technology – their preferred or prescribed Content Management System (CMS) and/or Learning Management System (LMS).

Educators who opted for a Web tool like Weebly, for example, were able to rely on the tool for both course content organization (as a CMS) and ePortfolio project development (as a platform). Those educators, who were more adventurous, chose to learn how to navigate the many functions of their LMS with a built-in ePortfolio application. Regardless of the choice of platform, key areas for consideration in ePortfolio technology are integration (to LMS, for example), flexibility (customization of layout), intuition (simple to use), and alignment (support of audio, visual, and text) as well as price (not all platforms are free). Learning to use the technology is a key factor in favourable project development experiences, as they impact successful completion of ePortfolios. From my perspective, when ePortfolio technology is implemented appropriately, it provides the proper pedagogical terrain for the cultivation of interaction and reflection where learners can thrive. It is the technology in ePortfolio projects that enables students to integrate resources, artefacts, multimedia, and reflective comments from various courses within one organized learning framework (Batson, 2010; Watson et al., 2016). It is well documented that for many years, ePortfolios were viewed as just another tool in a tech-tool kit used for instruction. Therefore, we necessitate discernment in understanding that learning the technology on its own does not enrich student learning (Eynon & Gambino, 2017). As argued by Watson et al. (2016),

ePortfolio pedagogy provides a set of practices that are platform agnostic and utilize a range of broadly available technologies. They are constructed within a framework for organizing learning and not as a prescription for a single end product, and they are designed to be owned and developed by the student learner with guidance from faculty and other educational professionals. (p. 65)

ePortfolio technology (platform, software, or management system) is flexible, accessible, and promotes engagement of students both with their own learning and with each other during project development.

Student Engagement

Research findings during the pandemic show evidence that online courses in general had insufficient quality standards (course design, support, and technology) at the time as well as inadequate learning activities, learner interaction, and learner support (Bates, 2022). Good teaching (online and in other modalities) relies on experiences that promote student engagement with learning activities and peers. A systematic review of what helped drive engagement of college students in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic included both instructor- and student-related factors. Student-student interaction was among the student aspects unveiled, which also included student self-efficacy, emotion, motivation, attitude, and personality traits (Limbu & McKinley, 2024). Since ePortfolio projects broaden student engagement in a deeper level of learning, they are a catalyst for positive outcomes (Eynon & Gambino, 2017), including meaningful and purposeful interaction with their projects and one another.

There are several determinants that contribute to the success (or failure) of online learning activities, and understanding learning characteristics is among them. Course demographics include an increasing number of diverse students, so it is important to identify ways to assist a wide range of learners with various levels of knowledge and abilities (Bates, 2019). Online environments are complex and demanding on all actors. Learners and educators begin to demonstrate levels of self-efficacy as they learn to self-regulate and shape their behaviour (Bandura, 1991) in their online environment– one of many predictors of engagement.

Another predictor of engagement is a combination of good course design and proper use of technology to channel some of the needs and interests of students (Bates, 2019). A course that includes ePortfolio implementation, as I have experienced, is undergirded by theories of learning, relies on student interaction, and promotes reciprocity among members of the ePortfolio community.

Alignment of Theoretical Principles

The explosion of new learning technologies during the pandemic gave rise to the implementation of online educational projects that denoted alignment with theoretical principles. ePortfolio projects are undergirded by theoretical constructs (technical, pedagogical, cognitive, and affective aspects) that manifest during various phases of the development process. As we revisit some of the traditional theories of learning – behaviourism, social learning theory, information processing theory, and individual and social constructivism—we are better equipped to understand the new pedagogical landscape. The evolving new technologies also necessitate that we learn about some of the contemporary theoretical principles that align with the thought processes of learners in the 21st century. Connectivism (knowledge as a network of connections in the environment) and ecological constructivism (knowledge constructed through interactions in the environment) align with the emerging learning principles and thought processes that result from the use of disruptive innovation in education. These theories of learning and other guiding principles help us gain an understanding of the contribution of social technological networks and human connections in this digital age as we engage in the recalibration of our teaching practice. Table 1 shows an at-a-glance view of some of the learning theories, how they are viewed, and why they tend to align with student behaviour at various stages.

Table 1

Learning Theories as they Align with ePortfolio Development (adapted from Zuba Prokopetz, 2022b, p. 2)

|

What

|

How

|

Why

|

|

Behaviourism (Skinner, 1953) |

Feedback interaction among peers |

Heeding information to improve artefacts |

|

Social Learning (Bandura, 1977) |

Reproduction of information |

Modeling to help peers; observing to help self |

|

Information Processing (Anderson, 1990) |

Making choices about what to include |

Strategizing to gain and apply new knowledge |

|

Constructivism: Individual, Social, Ecological (Piaget, 1970; Hoven & Palalas, 2016; Palalas, 2015) |

Working together to gain better understanding |

Collaboration to help with sense making and reliance on affordances of the environment |

|

Social Cultural (Vygotsky, 1978) |

Recognizing influence of culture on perception |

Gaining a broader view to include new knowledge in learning artefacts |

|

Connectivism (Siemens, 2005)

|

Connecting with peers during feedback giving and receiving |

Networking to create new avenues for learning in a collaborative process |

|

|

|

|

As illustrated above, these theoretical learning principles are present during various phases of an ePortfolio development, from attention to feedback information to decision-making, along with collaboration, cultural recognition, and connection.

PEDAGOGICAL LANDSCAPE

ePortfolios, initially regarded as a mere technology, a repository of learning samples, and an assessment tool, are now considered learning sites where educators and learners make their learning visible. In their paper-based format in the late 1980s, they were used in the context of education, mainly in writing courses. Since the advent of web technologies in the mid-1990s, the electronic version of portfolios emerged as a reimagined way of thinking about teaching and learning. The educational portfolio idea, adopted in writing and composition in the 1980s, first gained prominence in the education field in the mid-1990s in a paper-based format (Batson, 2015, 2018; Cambridge, 2010; Danielson & Abrutyn, 1997; Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Ravet, 2005). The impact of the portfolio as a new pedagogy in the early 1990s came as a surprise to initial users (Danielson & Abrutyn, 1997), especially to those educators whose modus operandi was knowledge dissemination rather than student engagement. Implementation necessitated training and guidance as well as an understanding of the portfolio components (what), the new way to facilitate instruction (how), and the rationale behind this new pedagogy (why). Proper training for early adopters of this pedagogy in their paper-based and, subsequently, electronic formats seemed inadequate at the time. Many instructors and students reported the project completion as time-consuming and ineffective (McMullan, 2006). Initially viewed as one more tool in a tech-tool kit of web technologies, ePortfolios are now an essential component of the pedagogy for transformative learning in any modality – online, in-person, and hybrid. They promote engagement of students both with their own learning (during the curation of artefacts) and with each other (during feedback interaction).

In their initial paper-based technology (1980-1990s), students were required to insert samples of their work in a three-ring binder for the purpose of formative and summative assessments. In their electronic version (mid-1990s and beyond), they capacitate the integration of resources, artefacts, multimedia, and reflective passages from various courses within one organized learning framework (Batson, 2010; Watson et al., 2016). Like the evolution in the design and facilitation of courses for online spaces, portfolios – and later ePortfolios – required designers and implementers to engage in a shift of mindset. This innovative and thoughtful pedagogy (Cuzzolino, 2018; Dron, 2020) continues to necessitate that those instructors, who may still view themselves as knowledge providers, transition from one-way interaction (lecturing students) to a multiple-way engagement modality in their role as facilitators to enable students to learn and demonstrate achievements. During the ePortfolio development process, the focus of educators is on student learning and the ability to navigate the learning process rather than merely “viewing the educational mission primarily in terms of providing instruction” (Chee, 2002, Abstract).

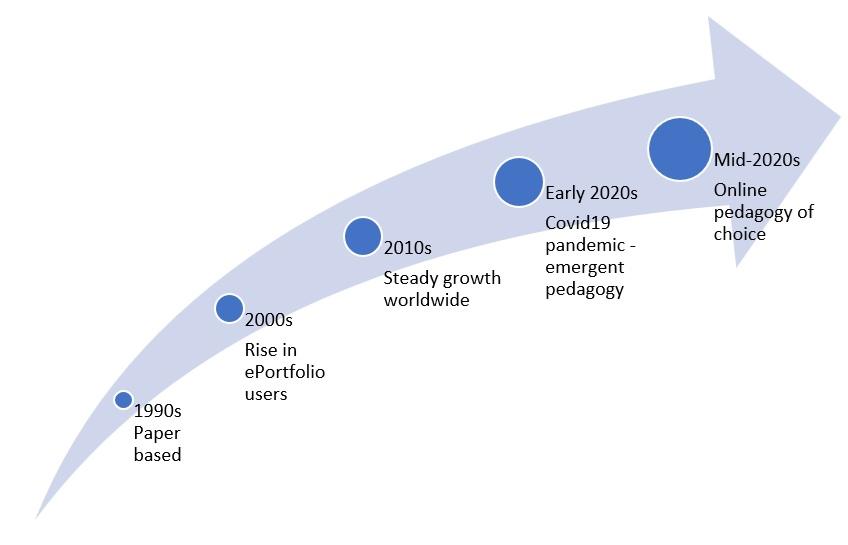

ePortfolios are an educational innovation that fosters new uses such as a capstone project of culminating experiences at the end of a course or program of studies. They are among the highly effective educational activities that require students to spend much time and effort in purposeful task completion (Kuh, 2008). As a result of their steady growth and evidence to support their usefulness in education, ePortfolios became part of the education practices considered to be of high impact (Kuh, 2008; Watson et al., 2016). This high-impact educational practice (Kuh, 2008; Watson et al., 2016) has positioned itself as an educational movement (Batson, 2015; Cambridge, 2010; Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Ravet, 2005) to help educators not only reimagine their thinking about teaching and learning but also transform the pedagogical landscape. The steady growth of ePortfolios worldwide in the early 2010s (Figure 1) stimulated interest in research and in peer-reviewed journal publications (Bryant & Chittum, 2013). The body of research-based evidence available in the early 2020s made it possible for educators during COVID-19 to (re)consider ePortfolio projects as their choice of pandemic emergent pedagogy. The entirely online environment, new to many during the pandemic, necessitated that students self-regulate (learning at their own pace and in their own time for the most part). This endeavour was a difficult one to undertake for many in the academy; educators were now students in their own classroom as they, too, had to learn to adapt and teach in innovative ways. Educators and students alike needed to rely on their self-regulative mechanisms to self-monitor, self-judge, and self-react (Bandura, 1991) to endure the road ahead as individuals in their new online platform where they would be learning, teaching, and communicating. This crucial communication during ePortfolio project development can now be streamlined with the use of AI tools that can read, respond to, and analyze large data sets of reflective passages and feedback interactions. This growing and readily available technology enables more efficiency (doing it well) and effectiveness (achieving desired results) throughout the ePortfolio development process, thus placing ePortfolio as the online pedagogy of choice moving forward beyond the 2020s.

Figure 1

ePortfolio Trajectory from 1990s to the mid-2020s

Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

In the late-1990s and early-2000s, the world experienced a significant shift in education because of the advancement of web technologies that enabled students to learn anywhere anytime. There were blogs, wikis, videos, and many other forms of self-published materials readily available; yet, there was a paucity of scholarly publication that included the ePortfolio practice. Literature denotes that the first proponents of ePortfolios had no blueprint or framework of how to proceed with the application of this technology in their practice since there was little research at the time (Cambridge et al., 2009). During the decade that preceded the pandemic, the ePortfolio gradually became a well-regarded concept (Batson et al., 2017; Hallan et al., 2008) albeit not yet fully embraced by many in the institution of education. Rather than being regarded as a technology-enabled emerging pedagogy (Batson, 2018; Zuba Prokopetz, 2019), the ePortfolio was viewed as a time-consuming endeavour (McMullan, 2006) due to its perceived complexity related to product (technology) and process (pedagogy). During the pandemic, however, ePortfolios were deemed important pedagogical tools in online education since they enabled not only students to demonstrate their thinking, learning, and attitudes (Zhang & Tur, 2024) but also instructors to adapt their teaching to the new context (Bates, 2019). By 2020, research and practice on ePortfolios was well documented in peer-reviewed journals, and there was a “drastic increase in ePortfolio articles over time” (Bryant & Chittum, 2013). Educators in search of a way to adapt their content to their students due to the new context (Bates, 2019) no longer felt they were applying what they knew about the ePortfolio concept before more research findings were available. ePortfolios had matured and could now be “packaged for broader consumption in the realm of practice” (Bryant & Chittum, 2013, p. 196). Educators in various fields of practice (e.g., engineering, nursing, and business) continue to seek ways to learn more about how to apply ePortfolio projects to support reflection in their attempt to help students learn better (Jayatilleke & Mackie, 2011; Sepp et al., 2015; Slepcevic-Zach & Stock, 2018).

Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic

As observed in a post-pandemic research study, there was a welcoming attitude toward ePortfolios during COVID-19 (Zhang & Tur, 2024). Online projects like ePortfolios were flexible in the new environment, and they made it possible for students to make their learning visible on an ongoing basis (Zhang & Tur, 2024). Courses that included reflective online projects like ePortfolios showed the digital resilience of the students – and their instructors – throughout the ePortfolio development process of curating, creating, reflecting, and presenting. Students gradually realized that they could embrace their ePortfolio experience – with both challenges and rewards – to leverage new knowledge and become proactive toward the learning ahead When students engaged in learning how to use the platform and making decisions about the layout, content, and artefacts for their projects, they experienced a shift in mindset that capacitated a positive attitude toward project completion (Zuba Prokopetz, 2022a). It was this process of self-learning, self-observation, self-judging, and self-response that assisted students in their personal agency and self-efficacy as they learned to self-regulate and shape behaviours and outcomes (Bandura, 1991). This experiential learning helped students realize their intrinsic potential to decide and act on their own and in collaboration with peers in their online environment. Among the current trends in technology in higher education is the adoption of collaborative approaches – fostered by ePortfolio projects. Projects that include group work promote interaction and sharing, but purposeful collaboration provides an environment that validates the construction of knowledge in blended spaces (Vaughan et al., 2013) as well as in other instructional modalities. ePortfolio pedagogy enables the development of purposeful projects for assessment, employment, reflective learning, and professional development (Butler, 2006; Chang, 2001; Wade et al., 2005; Zuba Prokopetz, 2019).

Enhancing ePortfolio Practices through AI-Driven Tools Technological advances with LLM and AI now offer additional options for both students and instructors during the creation of their ePortfolios. These tools engender more dynamism and creativity – for educators and learners – related to the reading and writing processes during the ePortfolio development (AISOP, 2024). These language tools can be trained and subsequently automated to promote ongoing engagement of the students with their projects through continuous revisions and improvement. They assist not only students with their writing but also instructors with real-time feedback on ePortfolio pages. They can also be included in innovative forms of ePortfolio assessment once there is more research-based evidence on how educators can harness the benefits of this new technology. A systematic review of assessment in microcredential programs has highlighted the importance of studies on optimizing assessment practices; it revealed an existing gap related to the integration of AI tools in current assessment practices (Moore et al., 2025). The inclusion of some form of AI during ePortfolio implementation may help bring a certain level of comfort during project development (real-time interaction) and further enhance the level of student engagement with course content, peers, and instructors. Once educators embrace the technology, they may experience the impact of this powerful pedagogy in the creation (of their own) and implementation (in their practice) of ePortfolio projects for their own learning and teaching. As Hoeppner (2024) presents in her podcast series for educators, learning designers, and educational leaders, students are beginning to use AI for digital presence curation as they create or update their ePortfolio projects for various courses and different purposes.

EPORTFOLIO PROJECTS

The ePortfolio project, a collection of pages with reflective passages aligned with program competency, is underpinned by a powerful pedagogy. The ePortfolio project application is manifold – assessment (mastery of subject matter); developmental (student growth); process (learning focused on feedback interaction); showcase (highlighting best work); and professional (demonstrating capabilities). As such, the different audiences for ePortfolios include teachers, lecturers, mentors, employers, and students in a learning community (Butler, 2006).

Research-based evidence supports the notion that an ePortfolio project helps enhance student learning as well as connect practitioners with their craft as facilitators of learning (Eynon & Gambino, 2017). A growing number of researchers and scholars in global higher education regard ePortfolio development as eliciting new ways of thinking to help with their teaching of students in the 21st century. During the ePortfolio developmental process, there is a sharing of experiences that helps students make their learning visible (Johnsen, 2012) and enables members of the group to benefit from each other’s knowing. This mutual exchange of knowledge, experiences, and support is becoming even more prevalent now. Students can store large amounts of data in AI chatbots that act as virtual assistants to facilitate peer-to-peer communication during feedback giving and receiving interaction. The AI data storage can be ongoing to include new individual achievements and employment. Once data accuracy has been established, the information can be easily repurposed for different types of ePortfolios based on specific audiences.

Types of ePortfolio Projects

The field of teacher education has been the leader in the use of ePortfolios (Butler, 2006). Student-teachers have been implementing this innovation (credential portfolios) to demonstrate their fulfilment of the requirements for a standardized level of teaching proficiency (Snyder, 1998) for a considerable amount of time. Candidates for a teaching license have long relied on their teaching (also learning) portfolio (Wolf & Dietz, 1998) to show the completion of their licensure requirements.

The initial types of portfolios were credential, learning, and showcase (Zeichner & Wray, 2001). With the emergence of educational technology, there was a fourth type, the process ePortfolio, that encompassed a variety of activities to facilitate the development of reflection of students (Barrett, 2010). The portfolio in a digital format has experienced many versions and has been referred to as a webfolio (Lorenzo & Ittelson, 2005), web-based portfolio, electronic portfolio, efolio, and digital portfolio (Lorenzo & Ittelson, 2005; Pitts & Rugirello, 2012). It experienced a humble beginning with the rise of web tools, and it is now a key project in online courses.

Projects such as ePortfolios are reflective (identification of strengths and weaknesses), demonstrative (visibility of skills and capabilities), and developmental since they foster student engagement in their own learning process in a course or program of studies.

Reflective ePortfolio Projects

ePortfolio projects that are reflective enable students to identify their strengths and weaknesses in their various assignments within a course and a program of studies. These online projects, a collection of evidence-based achievements, are born from moments of elation as well as frustration experienced by the students during project development. They enable students to pause and critically analyze their learning thus far, recognize areas for improvement, identify potential for growth, and articulate skills, knowledge, and behaviours resulting from ongoing self-reflection and metacognitive reasoning. As a capstone project, their key components are student-selected artefacts (evidence of learning), alignment with course or program competencies (evidence of achieving outcomes), and articulation of learning journey (presentation to demonstrate growth over time).

Metacognitive Reasoning Observed by an ePortfolio Course Facilitator

Educators that fully engage with the ePortfolio development process of their students – from the very beginning until the presentation day – tend to experience observable moments of metacognitive reasoning among course participants. It is by observing the ePortfolio reflective passages and feedback interactions that course facilitators can gain insights into the metacognitive thinking development of their students. Over the years, I have experienced firsthand the meaningful final course presentations of students (language learners, college educators, and graduate students) that embodied authenticity and clear articulation of goals. Student interaction throughout all phases of their projects was often (if not always) mentioned as a key component of their reflective journey. During these reflective thinking episodes, students expressed experiencing levels of learning that went from cognition to metacognition. The initial factual knowledge related to their selection of artefacts (what my learning was) brought forth analytical thinking during the curation of experiences (how I learned), and consequently, advanced to a much higher level of thinking (metacognition) regarding their decisions (rationale for my choices). The ePortfolio reflective journey capacitates the perception – and articulation – of levels of learning that go from cognition to metacognition (Marzano & Kendall, 2007) – course facts, learning process, and awareness of their thinking.

Demonstrative ePortfolio Projects

Also referred to as a showcase ePortfolio, this type of project promotes visibility of the skills and capabilities of students. The showcase ePortfolio serves as a platform for students to highlight achievements on a personal, academic, and professional level. The demonstrative ePortfolio makes it tangible for students to demonstrate key aspects of their learning, skills, and achievements. They are often used during job interviews instead of a résumé (for a new position), during performance review (for a possible promotion), and in applications for tenure (for a permanent appointment) since they contain evidence of stellar achievements.

Developmental ePortfolio Projects

A developmental ePortfolio project is comparable to a reflective ePortfolio project, and some teachers incorporate attributes of both types in their ePortfolio course implementation. The focus of a developmental ePortfolio is on what the learning was (tell me about your assignments); how it took place in a course or program of studies (tell me about your group work or research experience), and why it occurred in such a way (talk about the rationale for the learning that took place). These types of projects focus on the process of learning and tend to capture experiences as they develop. The developmental ePortfolio promotes reflection on learning experiences and facilitates the identification of strengths and weaknesses not only on an academic level, but also on a personal and professional one. Students are encouraged to set goals to enable them to leverage new findings and take ownership of the learning experiences ahead.

EPORTFOLIOS AS MULTIPURPOSE PEDAGOGICAL TOOLS

Projects like ePortfolios are viewed as multipurpose pedagogical tools. When ePortfolios are included in online courses, they perform not only as technological tools but also as instructional strategy and digital pedagogy. As technology, ePortfolios are shareable and accessible. The technology provides a platform (a blank canvas) that becomes a resource (rich with experiences) where students upload content and showcase their achievements. The technology enables instructors to view student work anytime, anywhere, provide ongoing feedback (on the artefact pages themselves), and assess the learning of their students at any point in time. In addition, now that students are beginning to use generative AI for the creation of their ePortfolios (Hoeppner, 2024), and instructors are harnessing automated feedback accessible from chat systems (AISOP, 2024), the potential for research studies on ePortfolio as an innovative pedagogical tool is unlimited.

ePortfolios are considered an innovative instructional strategy since the project development itself is a substrate for learner-instructor interaction and learner-content engagement, which results in a deeper level of learning. The project development phase makes it possible for students to interact with the technology as they discover its affordances in their online community of learners. As students curate evidence for their projects, they are not only showcasing learning experiences but also engaging in self-reflection related to their learning journey thus far.

ePortfolios are viewed as a powerful digital pedagogy since they capacitate interaction, deep learning, and critical reflection during all phases of project development. They include instructional practices for students to help with their learning (curating and creating content) and for their instructors to help with their teaching (course content facilitating).

As a capstone project (a compilation of learning evidence in a course or program of studies), ePortfolios show evidence of authentic learning episodes as artefacts. These artefacts are in alignment with reflective passages that tell a story of what the learning was (facts), how it occurred (process), and why it mattered (rationale).

My own experience as a practitioner in the field of education has necessitated that I view ePortfolio projects as pedagogical tools of many purposes since they embody attributes that promote awareness, self-assessment, reflection, and feedback interaction.

Reflection and Feedback Interaction

As learning strategies, reflection and feedback interaction are impactful in educational settings and underpin deep learning. To be effective, online learning and teaching environments necessitate a sense of community; student engagement with content and interaction with each other tend to promote community and relationship building. An ePortfolio capstone project, “an enabler for increasing meaningful personal contact” (Feldstein & Hill, 2016, p. 26), is a place where community members can engage in interaction with instructors, peers, and course content (Moore, 1989). When these projects are properly facilitated and expectations clearly communicated, they help foster collaboration through feedback giving and receiving. Feedback is a learning strategy; it embraces the exploration of perspectives on learning to date (from the feedback givers and feedback receivers). Feedback interaction promotes value on the projects of one another and encourages relationship building. Feedback giving and receiving on ePortfolios help promote project improvement – of content, layout, composition. This line of thinking during project development and completion helps students reflect on their learning to date (Barrett, 2004; Batson, 2018; Chen & Patel, 2017; Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Kuh, 2008; Penny Light et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2016).

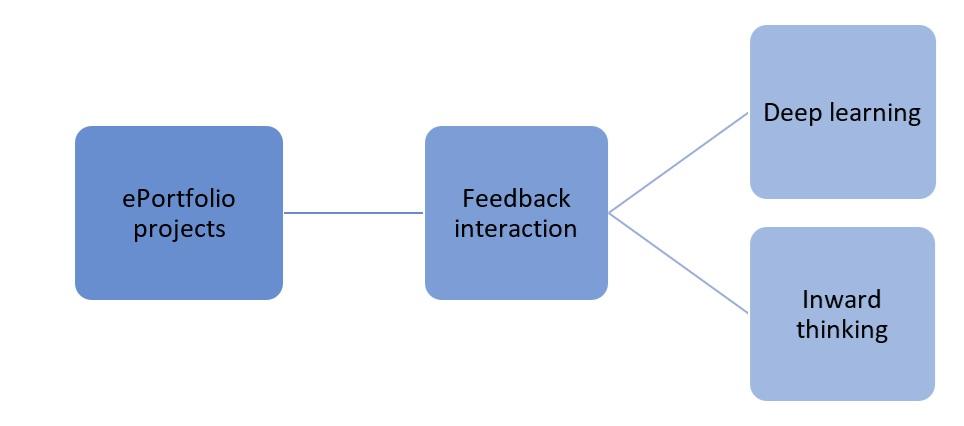

Awareness and Self-Assessment

ePortfolios promote awareness and assessment of self at various stages of the project development. Deep learning (knowledge of self and course content) and inward thinking (examination of goals and feelings) are the result of feedback interaction during the feedback-giving and feedback-receiving experiences (Figure 2). Upon receiving comments by instructors and peers on the ePortfolio pages, students begin to discern the scope of their journey thus far (awareness) and the possibilities for improvement (self-assessment) on their developing project before completion and final presentation.

Figure 2

Reflective Thinking Triggered by Feedback Interaction on ePortfolio Projects

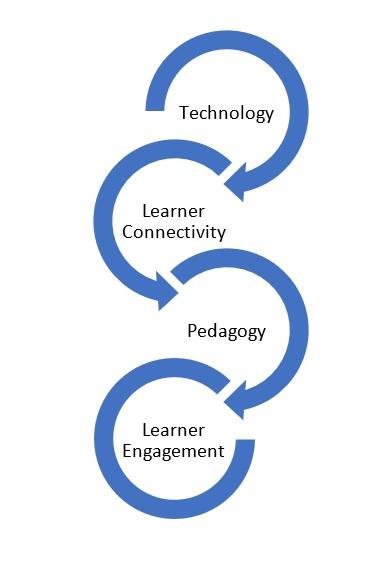

Students who engage with their project from the beginning (and even the ones who choose to do it later in the course) realize that this personalized – and quite intimate – experience brings forth moments of both trepidation and calmness. There are often (if not always) initial moments of frustration related to using the platform (technology), curating and creating of artefacts (pedagogy), receiving feedback from peers (interaction), and thinking reflectively about the significance of the learning thus far (reflection). The technology capacitates interaction, and feedback interaction promotes reflection on the new information received. These reflective thoughts trigger moments of self-awareness and self-assessment regarding the current level of knowing. These four constructs—technology, pedagogy, interaction, and reflection are interwoven and help engender feelings of tranquility when they work in tandem.

INTERPLAY OF TECHNOLOGY AND PEDAGOGY IN EPORTFOLIOS

During COVID-19, when educational actors were thrust into online spaces with no requirement of prerequisite skills, online projects were a challenge for those new to learning with technological tools. ePortfolio projects rely as much on the pedagogy (guiding the learning experience) as they do on the technology (experimenting with different platforms). As such, ePortfolio project efficacy (meeting the desired course outcomes) espouses reciprocal relationship between technology and pedagogy.

While ePortfolio technology has become an exemplar for connectivity and interaction in global education (Batson, 2018), ePortfolio pedagogy is now situated prominently in higher education because it embraces – and facilitates – learner engagement in online spaces (Figure 3). ePortfolio projects are an innovative learning and teaching strategy since they espouse active and mindful learning throughout the development process. This pedagogical approach is interwoven by thoughtful engagement of the learners with content, their questioning of the status quo, and their consideration of their own decisions, values, and positionality (Langer, 1997).

Figure 3

Learner Connectivity and Engagement in ePortfolios

INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGY

ePortfolios are among the effective instructional strategies that enable students to leverage technology to enrich their learning experiences. They promote connection between moments of elation and frustration and help interaction among members of the ePortfolio learning community. As students develop their projects, they experience learning with the technology (knowledge acquisition) while learning how to use it (knowledge application). Learning which is mediated by ePortfolio technology espouses self-awareness and critical reflection and makes affordances for self-reflection and a better understanding of values, motivations, and both strengths and weaknesses.

When we experienced the sudden move to online spaces resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, educational platforms such as ePortfolios offered an innovative instructional approach to help make learning engaging for students and visible for instructors in digital spaces. As digital instructional strategy, ePortfolio projects help educators organize course instruction, facilitate online teaching, and enhance student learning (Yancey, 2019). They foster quality in teaching, adhere to theoretical principles, and support learning activities that are innovative, interactive, and conducive to reflection. ePortfolio project implementation at course level strengthens course design and align with standards of course quality and good teaching. Quality standards, although required in all modes of teaching, are less about the delivery mode and more about the teaching itself (Bates, 2022). Projects that are reflective, like ePortfolios, help enhance both course instruction and student learning.

CONCLUSION

Teaching that occurs in online spaces is extremely complex, as engaging learners and educators in online activities is a challenging endeavour. Educators who focus their course design (and subsequent facilitating) on student learning tend to adopt instructional strategies that go beyond content uploading and lecturing. Regardless of the modality, a well-designed course format is cemented by instructional tools that foster student interaction. Courses that implement projects like ePortfolios (viewed as multipurpose pedagogical tools) foster reflection, enable interaction, and bring forth metacognition. In online courses, ePortfolios perform not only as technological tools but also as instructional strategies and digital pedagogy. This digital pedagogy promotes awareness, self-assessment, reflection, and feedback interaction. ePortfolios are reflective since they help students identify their strengths and weaknesses. They are demonstrative, as they enable visibility of skills and capabilities. They are also developmental, for they foster student engagement in their own learning process in a course or program of studies. Educators who have implemented ePortfolios in their practice support the belief that ePortfolios help enhance interaction among students and their instructors. As a powerful educational strategy, ePortfolios display student performance over time and serve as student measurements of personal and academic attributes. ePortfolio activities, a powerful pedagogical approach, encourage and facilitate deeper learning, reflective moments, guided collaboration, and purposeful interaction. These ePortfolio activities are important in student development of intellectual strength and capabilities. As a substrate for student awareness, self-assessment, and metacognitive reasoning, they engender a higher level of thinking regarding decisions made and performance over time. While documenting their work, students embrace strategies that make their learning process visible. While interacting with one another, students apply techniques to engage in purposeful collaboration. While developing their ePortfolios as a course assignment, students demonstrate their digital resilience during the curation, creation, reflection, and presentation of their projects. Throughout the development process, students learn to embrace their ePortfolio experience (during not only joyful times but also trying moments) to leverage new knowledge toward the learning experiences ahead. Courses that include ePortfolio development are underpinned by reflection and rely on feedback interaction as pedagogical strategies that help students engage with peers, content, and the project itself. Moving forward, continuous feedback on ePortfolios – facilitated by AI tools – may lead to ongoing reflection on learning and more collaborative real-time communication that further strengthens student engagement with their learning.

REFERENCES

AISOP. (2024, September 9). EPEPLA Workshop: E-Portfolio Evolution Powered by Language Analysis. https://aisop.de/EPEPLA

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teacher presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v5i2.1875

Anderson, J. R. (1990). Cognitive psychology and its implications (3rd ed.). Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Barrett, H. C. (2010). Balancing the two faces of ePortfolios. Educação, Formação & Tecnologias, 3(1), 6–14. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZYiP3Z3lTx4nssNoDjMUTWTS2D3Vw5r9/view

Barrett, H. C. (2004). Electronic portfolios as digital stories of deep learning: Emerging digital tools to support reflection in learner-centered portfolios. http://electronicportfolios.org/digistory/epstory.html

Bates, T. (2022, March 22). Define quality and online learning. Online Learning and Distance Education Resources. https://www.tonybates.ca/2022/03/24/defining-quality-and-online-learning/

Bates, T. (2019). Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for designing teaching and learning. 2nd ed. Anthony Williams (Tony) Bates. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev2/

Batson, T. (2018). The ePortfolio idea as guide star for higher education. AAEEBL ePortfolio Review, 2(2), 9-11. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B5EyRIW5aG82dGtQTjJEcVk2R21JazZuRjFyb3BucVBMbUFZ/view

Batson, T., Coleman, K. S., Chen, H. L., Watson, C. E., Rhodes, T. L., & Harver, A. (Eds.). (2017). Field guide to ePortfolio. Association of American Colleges and Universities. https://aportfolio.appstate.edu/sites/aportfolio.appstate.edu/files/field_guide_to_ePortfolio.pdf

Batson, T. (2015, February 2). Study shows steady growth in ePortfolio use: What does that mean? https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZVXXO2bmCoHXcM1ZYV20ejxiOw8kjJdC/view

Batson, T. (2010). Review of portfolios in higher education: A flowering inquiry and inventiveness in the trenches. Campus Technology Website. https://campustechnology.com/articles/2010/12/01/review-of-portfolios-in-higher-education.aspx

Benito-Osorio, D., Peris-Ortiz, M., Armengot, C. R., & Colino, A. (2013). Web 5.0: The future of emotional competences in higher education. Global Business Perspectives, 1(3), 274-287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40196-013-0016-5

Bryant, L. H., & Chittum, J. R. (2013). ePortfolio effectiveness: A(n ill-fated) search for empirical support. International Journal of ePortfolio, 3(2), 189-198. http://www.theijep.com/pdf/ijep108.pdf

Butler, P. (2006). A review of the literature on portfolios and electronic portfolios. Massey University College of Education. https://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/download/ng/file/group-996/n2620-ePortfolio-research-report.pdf

Cambridge, D. (2010). ePortfolios for lifelong learning and assessment. Jossey-Bass.

Cambridge, D., Cambridge, B., & Yancey, K. (Eds.). (2009). Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact. Stylus.

Chang, C. (2001). Construction and evaluation of a web-based learning portfolio system: An electronic assessment tool. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 38(2), 144-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/13558000010030194

Chee, Y. S. (2002). Refocusing learning pedagogy in a connected world. On the Horizon, 10(4), 7-13. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120210452102

Chen, H. L., & Patel, S. J. (2017). Portfolio to professional: Supporting graduate student reflection via digital, evidence-based storytelling. AAEEBL ePortfolio Review, 1(2), 7-14. https://drive.google.com/file/d/12onoGBiKIKXzfEcKcyW_vYTsO4hS0v2Y/view

Croft, N., Dalton, A., & Grant, M. (2015). Overcoming isolation in distance learning: Building a community through time and space. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 5(1), 27–64. https://doi.org/10.11120/jebe.2010.05010027

Cuzzolino, M. P. (2018, May 29). Thoughtful pedagogy can support science learners grappling with epistemological conflict. https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/responses/thoughtful-pedagogy-can-support-science-learners-grappling-with-epistemological-conflict

Danielson, C., & Abrutyn, L. (1997). Introduction to using portfolios in the classroom. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/197171/chapters/Introduction.aspx

Dron, J. (2020, September 11). Skills lost due to COVID-19 school closures will hit economic output for generations (hmmm). https://landing.athabascau.ca/bookmarks/view/6578662/skills-lost-due-to-covid-19-school-closures-will-hit-economic-output-for-generations-oecd-cbc-news

Eynon, B., & Gambino, L. M. (2017). High-impact ePortfolio practice: A catalyst for student, faculty, and institutional learning. Routledge.

Feldstein, M., & Hill, P. (2016). Personalized learning: What it really is and why it really matters. EDUCAUSE Review, 51(2), 25-35. https://er.educause.edu/-/media/files/articles/2016/3/erm1622.pdf

Hallan, G., Harper, W., McGowan, C., Hauville, K., McAllister, L., & Creagh, T. (2008). Australian ePortfolio project: ePortfolio use by university students in Australia: Informing excellence in policy and practice. QUT Department of Teaching and Learning. https://ltr.edu.au/resources/grants_project_executivesummary_ePortfolios_oct08.pdf

Hoeppner, K. (Host). (2024, June 12). Mario A. Peraza: Use AI to help curate your digital presence (No. 46) [Audio podcast episode]. In Create. Share. Engage. https://podcast.mahara.org/2018360/episodes/15176788

Hoven, D., & Palalas, A. (2016). Ecological constructivism as a new learning theory for MALL: An open system of beliefs, observations and informed explanations. In A. Palalas & M. Ally (Eds.), The international handbook of mobile-assisted language learning (pp. 113-137). China Central Radio & TV University Press Co., Ltd. http://www.academia.edu/27892480/The_International_Handbook_of_Mobile-Assisted_Language_Learning

Jayatilleke, N., & Mackie, A. (2011). Reflection as a part of continuous professional development for public professionals: A literature review. Journal of Public Health, 35(2), 308-312. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds083

Johnsen, H. L. (2012). Making learning visible with ePortfolios: Coupling the right pedagogy with the right technology. International Journal of ePortfolio, 2(2), 139-148. https://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP84.pdf

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities. http://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/High-Impact-Ed-Practices1.pdf

Langer, E. J. (1997). The power of mindful learning. Hachette Books.

Limbu, Y. B. & McKinley, C. (2024). Factors associated with student engagement in online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Online Learning, 29(1), 293–322. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v29i1.4221

Lorenzo, G. & Ittelson, J. (2005). An overview of e-portfolios. Educause Learning Initiative – advancing learning through IT innovation. https://library.educause.edu/-/media/files/library/2005/1/eli3001-pdf.pdf

Marzano, R. J., & Kendall, J. S. (2007). The new taxonomy of educational objectives (2nd ed.). Corwin Press.

McMullan, M. (2006). Students’ perceptions on the use of portfolios in pre-registration nursing education: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(3), 333-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.05.005

Moore, R. L., Lee, S. S., Pate, A. T., & Wilson, A. J. (2025). Systematic review of digital microcredentials: Trends in assessment and delivery. Distance Education, 46(1), 8–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2024.2441263

Moore, M. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08923648909526659

Palalas, A. (2015). The ecological perspective on the ‘anytime anyplace’ of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning. In E. Gajek (Ed.), Technologie mobilne w kształceniu językowym, pp. 29-48.

Penny Light, T., Chen, H. L., & Ittelson, J. C. (2012). Documenting learning with ePortfolios: A guide for college instructors. Jossey-Bass.

Piaget, J. (1970). Genetic epistemology. Columbia University Press.

Pitts, W., & Ruggirello, R. (2012). Using the e-Portfolio to document and evaluate growth in reflective practice: The development and application of a conceptual framework. International Journal of ePortfolio, 2(1), 49-74.

Ragan, L.C. (1999). Good teaching is good teaching: An emerging set of guiding principles and practices for the design and development of distance education. Cause/Effect Journal, 22(1). https://www.educause.edu/ir/library/html/cem/cem99/cem9915.html

Ravet, S. (2005). ePortfolio for a learning society [Paper presentation]. ELearning Conferences, Brussels. https://www.academia.edu/1073713/ePortfolio_for_a_learning_society

Salta, K., Paschalidou, K., Tsetseri, M., & Koulougliotis, D. (2022). Shift from a traditional to a distance learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Science & Education, 31(1), 93-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00234-x

Sepp, L. A., Orand, M., Turns, J. A., Thomas, L. D., Sattler, B., & Atman, C. J. (2015, June). On an upward trend: Reflection in engineering education. Proceedings of the 122nd Annual American Society for Engineering Education Conference & Exposition Higher Education, Seattle, WA, USA. https://doi.org/10.18260/p.24533

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1) 3-9. http://www.itdl.org/journal/jan_05/Jan_05.pdf

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

Slepcevic-Zach, P., & Stock, M. (2018). ePortfolio as a tool for reflection and self-reflection. Reflective Practice, 19(3), 291-307. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1437399

Snyder, J., Lippincott, A., & Bower, D. (1998). The inherent tensions in the multiple uses of portfolios in teacher education. Teacher Education Quarterly, 25(1), 45-60.

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Athabasca University Press. https://www.aupress.ca/app/uploads/120229_99Z_Vaughan_et_al_2013-Teaching_in_Blended_Learning_Environments.pdf

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. MIT Press.

Wade, A. Abrami, P. C., & Sclater, J (2005). An electronic portfolio to support learning. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 31(3), 25-30. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1073692.pdf

Watson, C. E., Kuh, G. D., Rhodes, T., Light, T. P., & Chen, H. L. (2016). Editorial: ePortfolios—The eleventh high-impact practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 6(2), 65-69. http://theijep.com/pdf/IJEP254.pdf

Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1761641

Wolf, K., & Dietz, M. (1998). Teaching portfolios: Purposes and possibilities. Teacher Education Quarterly, 25(1), 9-22.

Yancey, K. B. (Ed) (2019). ePortfolio as curriculum: Making models and practices for developing students’ ePortfolio literacy. Stylus.

Zeichner, K., & Wray, S. (2001). The teaching portfolio in US teacher education programs: What we know and what we need to know. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(5), 613-621.

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2024). A systematic review of e-Portfolio use during the pandemic: Inspiration for post-COVID-19 practices. Open Praxis, 16(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.16.3.656

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2022a). ePortfolio pedagogy: Stimulating a shift in mindset. The Open/Technology in Education, Society, and Scholarship Association Journal, 2(1), 1–19. https://journal.otessa.org/index.php/oj/article/view/27

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2022b). A reflection upon capstone ePortfolio projects and their alignment with learning theories. International Journal of ePortfolio, 12(1), 1-15. http://www.theijep.com/pdf/IJEP388.pdf

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2019). Capstone electronic portfolios of master’s students: An online ethnography [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Athabasca University. https://dt.athabascau.ca/jspui/handle/10791/300

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2018). Professional self-development mediated by ePortfolio: Reflections of an ESL practitioner. TESL Canada Journal, 35(2), 156-165. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v35i2.1295

AUTHOR

Dr. Rita Zuba Prokopetz is an educational consultant and independent scholar who conducts research on the application of electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) for teaching and learning. Since she completed her first ePortfolio in the early 2010s, she has implemented it as a capstone project in courses she facilitated for language learners, college educators, and graduate students. As a doctoral student, she conducted an online ethnography of graduate students as they created their capstone projects and presented them as a final defence in the last course of their Master of Education program of studies. Her chapter on ePortfolio pedagogical strategies shares her insights and perspectives based on her personal experiences with capstone projects both as a learner and educator.

Email: gprokope@mymts.net