35 Critical Reflection and ePortfolio Practice as a Journey Towards Transformative Learning

Kate Mitchell, The University of Melbourne

Kashmira Dave, University of New England

Asli Mccarthy, The University of Melbourne; Australia

ABSTRACT

Higher education is at a critical juncture, requiring a re-evaluation of its purpose and approaches to assessment in a post-pandemic, digitally and AI-driven world (Lodge et al., 2023). Researchers (Bearman, Tai, et al., 2024; Lodge et al., 2023) emphasise the need for teaching and assessment practices that foster evaluative judgment, reflection, and critical thinking. We argue that critical reflection is a key practice needed to enable transformative learning (Mezirow, 1981), supporting identity reconstruction, well-being, and the development of a resilient “symphonic self” (Cambridge, 2008) for this modern context.

Despite its significance, both students and educators often struggle to engage in deep reflective practice, and the shift from reflective to transformative learning is particularly challenging. Existing literature on transformative learning and critical reflection tends to focus on theoretical or conceptual perspectives rather than offering practical guidance that educators can use. This gap highlights the need for actionable models that support critical reflection in discipline-specific, cross-disciplinary, and interdisciplinary contexts, particularly in health sciences, where reflective practices and ePortfolios are industry requirements.

This chapter reviews common themes in the literature and presents a step-based model to support teaching staff to embed critical reflection as a crucial step both towards ePortfolio high impact practice and transformative learning. Building on Mezirow (1981) and Fook and Gardner (2007), our model integrates ePortfolio and dialogic feedback practices to support transformative learning and identity development in the post-pandemic era. While developed with health professions education in mind, the model is adaptable to other disciplines, offering educators practical tools to foster critical reflective practices and drive transformative change in higher education.

Keywords: critical reflection, ePortfolios, transformative learningP, Digital learning environments

INTRODUCTION

In our current world and current educational landscape, we are at a turning point. Higher Education (HE) has pivoted from one crisis to another rapidly. First, a pandemic, where educators were asked to incorporate technology quickly and rethink the place and mode of learning. With the emergence of generative artificial intelligence (AI), HE sees a crisis of academic integrity and the role and purpose of education. Generative AI changed the landscape of what can be done by machines and calls into question what work will be left for humans to undertake, and as such, what knowledge is worth knowing.

In Australia, broader discussions of what is worth knowing have included recognition of the need to prioritise transferrable skills relevant to lifelong learning, such as critical reflection and evaluative judgement (Bearman, Castanelli, et al., 2024; Lodge et al., 2023; Tai et al., 2018). Such skills enable us to analyse, question, and reflect on outputs we may receive from AI, evaluate the quality of these outputs, and consider and unpack potential biases in such outputs. They are metacognitive skills relevant to problem solving but also needed to calibrate our own skills gaps and areas for development and improvement. They can also help us understand our role, purpose, values, and place within society. As such, they are skills that we would argue are required for not just self-assessment but self-understanding. As individuals continue to live in an increasingly ambiguous, rapidly shifting, and complex world, they will likely need more tools to be able to make sense of the world and their own role within it.

Critical reflection, as defined by Arend et al. (2021), is differentiated from reflection in that it aligns more closely to critical thinking and assumes deliberate intent to review complex problems and/or one’s role and positionality within systems and power structures (aligned to critical theory). Critical reflection thus offers two-fold importance and benefits for students living in a post-pandemic world: a) helping students to build techniques to support dealing with complex and wicked problems and to devise novel solutions to such problems; and b) opportunities to rethink power relations as needed to advocate for and make change within existing systems. Critical reflection may additionally support students in building broader conceptions of self and a greater ability to align and make sense of tensions between personal values compared to systemic challenges in practice (Fook & Gardner, 2007). We would argue that critical reflection is therefore necessary as part of a transformative learning experience and as part of relevant ongoing professional resilience in the age of AI, but it is also important for personal resilience and well-being in a post-pandemic world.

ePortfolios are sites for student creativity (Coleman, 2017), agency (McLellan, 2021), and potential identity transformation (Nguyen, 2013; Torres & McKinley, 2023), allowing students to build holistic representations of self and identity as a ‘cohesive narrative’ (Nguyen, 2013). ePortfolios are, as such, flexible and useful tools and forms to support and evidence the transformative learning process. ePortfolios not only account for but also emphasise reflection and reflective practice. Teaching with ePortfolios also requires educators to rethink their own positionality and role as authority (McLellan, 2021; Polly & Coleman, 2024), which we would argue is a key component to enacting teaching practices aligned to and more likely to result in transformative learning in students.

In this manuscript, we make a case for the role of critically reflective practice in education and discuss how critical reflection and ePortfolio practices can support educators and students to recognise their positionality, build community-mindedness and resilience towards transformative action. We then offer a model to support educators in implementing teaching strategies for reflective practices that may be more likely to lead to critical reflection and transformative learning outcomes. Our model is founded on transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1981; 1990) and references pedagogies, technologies, and practices (such as ePortfolios) that we feel provide concrete supports to teaching critical reflection toward transformative learning. While this chapter focuses on health professions, we argue that anyone who works within systems (especially individuals who are social justice or inclusivity-focused in their work) would benefit from undertaking critical reflection toward transformative learning. This would include those within not just health sciences but a range of other professional fields.

BACKGROUND

Defining Critical Reflection and Transformative Learning

We want to first note the difference between reflection, critical reflection, and critical reflection for transformative learning, as these are, in our minds, related but different concepts. Our definition of critical reflection for transformative learning is rooted in Mezirow’s concept of transformative learning theory. Mezirow argues that transformative learning cannot occur without a level of critical reflection, a type of reflection Mezirow termed ‘premise reflection’ (refer to Mezirow (1990), Kitchenham (2008), and Lundgren & Poell (2016)). Mezirow (1990) defines premise reflection as seeing the larger view of what is operating within our value system. He suggests that premise reflection leads to a profound change in an individual’s perspective (meaning transformation).

Fook (2021) and Fook and Gardner (2007) conceptualise critical reflection as socially and professionally contextually situated. They equate critical reflection to reflexivity and a clear linking and sense-making between theory and practice. Brookfield (2017) defines critical reflection as analysing discourses of power and questioning hegemonic assumptions about practice and positionality – identifying commonplace assumptions about power and power dynamics that are not serving the individual and are actively harmful to well-being.

These authors connect critical reflection to concepts of power, systemic injustice, well-being, and the tension between agency and responsibility of individuals working within systems to improve the systems for others. Such challenges are particularly relevant to those in health professions likely to be managing the care of both clients and themselves while working within complex, imperfect systems.

The Need for Critical Reflection in Health Professions

For Employability

- Reflective practice and professional reflexivity is becoming increasingly expected for employability in health services. For example:

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Professional Performance Framework recognises self-reflection as a required capability to deliver quality patient care, self-care practices, and well-being (RACGP, 2022).

- The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (Nursing & Midwifery Board of Australia, 2016) recognises reflective practice as an essential competency for nursing practice (particularly within Standard 1.2 of the Registered Nurse Standards for Practice).

- The Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) National Practice Standards for Nurses in General Practice prioritise critical reflection, particularly for Registered Nurse (RN) level and above, such as: ‘Regularly undertake critical reflection on the quality of their individual clinical practice and nursing services within the practice’ (ANMF 2014, Standard 12, p.28).

- The Australian Dental Council (ADC) requires newly qualified dental practitioners to be able to apply clinical reasoning and judgement in a reflective practice approach to oral health care (Australian Dental Council, 2022). The ADC defines critical thinking as “… a willingness to examine beliefs, biases, and assumptions and to search for evidence that supports the acceptance, rejection, or suspension of those beliefs, biases, and assumptions” (Australian Dental Council, 2022 p.7).

These examples from health sciences professional standards not only demonstrate the importance and value of reflection but also the increasing need to prioritise critical reflection specifically as part of clinical training and clinical practice.

For Well-being and Resilience

Reflective practice is for more than ensuring care for the patient or client. It is about self-care. The literature documents rates of burnout, stress, and mental health concerns among students in within medical education (Hope & Henderson, 2014). Similar patterns have been observed across nursing, pharmacy, and other health professions students (Rudman & Gustavsson, 2012). Several factors contribute to these challenges. The demanding nature of health sciences education, with its heavy workload, high-stakes assessments, and exposure to human suffering, creates significant stress (Slavin et al., 2014). Additionally, the culture of perfectionism and the hidden curriculum in many health professions can undermine resilience by stigmatising vulnerability and help-seeking behaviours (Hafferty & Franks, 1994).

Interventions to support resilience, such as mindfulness-based programs, reflective practice groups, and mentoring relationships, have demonstrated positive effects on wellbeing and resilience (Regehr et al., 2014). However, these interventions often focus on individual coping rather than addressing systemic factors that contribute to stress and burnout.

Reflective practice is increasingly acknowledged as a valuable strategy for managing the emotional toll of healthcare work (Clinical Excellence Commission, 2022), seeing increased motivation and empowerment (Fook & Gardner, 2007), and decreasing job turnover (Clinical Excellence Commission, 2022). ePortfolios additionally show promise in supporting well-being, though ePortfolio technologies can additionally act as stressors (McCarthy et al., 2024).

Identifying Critically Reflective Practices in Health Sciences

If reflective practice is required for clinical practice and wellbeing, it is important that health professions educators are able to recognise the breadth of critically reflective practice in context, and to train and support students to effectively undertake these practices. Health professions students and educators however may not be aware of what reflection and critical reflection look like in practice.

In complex systems such as healthcare, there is a need to employ both single-loop and double-loop learning (Argyris and Schön, 1978) at different times. Argyris and Schön (1978) define single loop learning as a point of reflection and correction that may happen as day-to-day practice where an alternative strategy is needed to perform a task, but the core values or ways of doing things are not challenged. Reflexivity (reflection in action, self-awareness) as an everyday activity may be required to ensure safe practice and respond to dynamic situations (Iedema, 2011). Double-loop learning (often considered equivalent to premise reflection) occurs when the underlying policies, values, and ways of doing things are no longer fit for purpose and are challenged and modified as a result. As an example, Engström (2000) described the process of collaborative reflective and discursive work to analyse and redesign complex patient care systems involving multiple interprofessional healthcare teams and how doing so improved outcomes for patients.

These examples demonstrate reflection as a form of everyday problem-solving and that deep critical reflection may be undertaken individually or collaboratively in healthcare settings in ways that may disrupt existing protocols, systems and even health professionals’ own assumptions and formalised codes of conduct. It is therefore imperative that critical reflection can be adequately taught to future healthcare professionals within educational settings.

Critical Reflection and Transformative Learning Through ePortfolios

In this section, we highlight the role of ePortfolios to support critically reflective activities for individuals’ greater awareness and meaning-making relevant to transformative learning. Such practices are relevant for both students and educators. Throughout the critical reflection process, students need to reflect on and review past assumptions, and to plan, reflect on and demonstrate change over time – activities that are heavily enabled by, if not reliant on, ePortfolios and portfolio practices.

ePortfolio is a term that can refer both to a digital portfolio (a collection of artefacts presented in a digital presentation format) and an ePortfolio platform (the technology that allows for building one or more digital portfolios and the repository for storing artefacts and reflections). ePortfolio advocates may also refer to ePortfolio pedagogies and practices, which include practices related to reflection, curation, and presentation. Using ePortfolios (all definitions), individuals such as students can purposefully reflect on their learning and progress, capture evidence and artefacts related to their identity or journey, and curate and present a selection of these artefacts and reflections for different purposes and audiences (Coleman, 2017).

ePortfolios have been defined as a high-impact practice, as when undertaken in a pedagogically sound, deliberate, and well-supported way, they can result in elevated student performance and deep learning (Watson et al., 2016). Polly & Coleman (2024) relate such high-impact practices not just to deep learning but to transformative learning.

Being a digital medium, ePortfolios offer additional options for students to connect theory to practice, and classroom to workplace in more seamlessly integrated ways (Cambridge, 2008; Clarke & Boud, 2016). Various authors (Arend et al., 2021; Fook and Gardner, 2007), for example, highlight the use of journals and other tools for participants to regularly capture reflections as well as other media such as art. Additional benefits to using ePortfolios for transformative learning are the ability to both look back and look forward. Reflecting on previous reflections and artefacts as a form of meta-reflection provides opportunities to recognise change and growth that has occurred over time (Nguyen, 2013).

Both Cambridge (2008) and McLellan (2021) highlight the role ePortfolios can play in challenging existing discourses of power depending on their use and framing. Both authors advocate for ePortfolios to enable critical conversations and the unique ability of ePortfolios as multimodal devices to tell particular “life narratives” (Cambridge, 2008). Students can thereby potentially reclaim agency over their own narrative and challenge existing teacher norms, assessment practices or teaching inequities by contributing to a dialogic transformative learning process using ePortfolios.

For educators, ePortfolio technologies typically support flexibility and multimodality and thus can support educators in more equitable practices. For example, ePortfolio multimodality, which encourages student agency and choice, can support teaching and learning practices aligned to Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Cambridge argues ePortfolios can and should be used to “contribute to creating agency, satisfaction, and meaning” in students’ lives more holistically (Cambridge, 2008, p. 245). The flexibility offered encourages educators in ‘letting go’ more freely of control or authority, which is a philosophical change that is arguably needed if wishing to engage in aligned teaching such as critical pedagogy (hooks, 1994).

High-impact practices have a cumulative positive effect over time (Watson et al., 2016). However, Watson et al. (2016) note that ePortfolio high-impact practice is predicated on appropriate pedagogical and technological implementation, change management, and support. Reflective practice and transformative learning likewise will require time and support for change to occur. Prioritising longitudinal habitual practice and well-supported implementation for ePortfolios will likely see benefits for transformative learning.

Methodological and Teaching Principles for Critical Reflection and Transformative Learning

If we, as educators, would like to encourage teaching practices that move students towards transformative learning, it is imperative that strategies that promote and support critically reflective practice are part of the teaching approach. Currently, there is a gap in the literature on how to go about this.

Lundgren and Poell (2016) and Harvey et al. (2025) have both undertaken detailed literature reviews related to operationalising critical reflection. Lundgren and Poell (2016) concluded that there is little consensus or clarity on operationalising and assessing critical reflection, and Harvey et al. (2025) noted a dearth of literature on the ‘how to.’ As Fook and Gardner note, “It seems that the conundrum of critical reflection is that everyone thinks it should be done, but when it comes down to the detail, many people are not sure specifically what is involved” (Fook & Gardner, 2007, p. 12).

Kitchenham (2008) notes that Mezirow’s concept of transformative learning is predicated on two key underpinnings: self-reflection on assumptions, and critical discourse validating a best judgment. We have therefore looked to Mezirow and to others who advocate for critically reflective teaching practices as a base for devising more specific strategies. Mezirow (see Kitchenham, 2008) suggests ten phases of transformative learning, through which individuals move to reach a level of transformation:

- A disorienting dilemma

- A self-examination with feelings of guilt or shame

- A critical assessment of epistemic, sociocultural, or psychic assumptions

- Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change

- Exploration of options for new roles, relationships and actions

- Planning a course of action

- Acquisition of knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans

- Provisional trying of new roles

- Building of competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships

- A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by one’s perspective.

Harvey et al. (2025) are specifically concerned with how critical reflection can be taught or integrated as part of teaching practice. Harvey et al. (2025) are not specifically addressing Mezirow’s concept of critical reflection, and their study has a number of limitations (including but not limited to, the narrow scope of the study, drawing from only one journal). However, they offer eight principles for reflective practice in teaching and learning that are relevant to critical reflection: Learn how to reflect, Make time (to reflect), Set the scene, Scaffold, Practice and experiment, Offer multiple modes, Assess with care, and Be scholarly.

Fook & Gardner (2007) likewise offer a range of principles for teaching critical reflection aimed at small group learning, which follow similar themes. Their process is primarily split into two phases:

- A phase of “unsettling the fundamental assumptions that are implicit in their account of their practice experience” (p.44), and

- A phase focused on how their practice or the conceptualisation or understanding of their practice is changing as a result of new awareness.

Some key principles they highlight align to Mezirow and include learning through dialogue and through individual reflection, a trusting and collegiate climate, ensuring shared commitment, teacher modelling and vulnerability, using critical reflective questioning and group facilitation, and using specific examples and concrete experience.

Other authors have offered similar ideas for supporting critical reflection processes. Arend et al. (2021) suggest defining critical reflection, scaffolding engagement in critical reflection, identifying critical reflection, and promoting the value of critical reflection. Such strategies align with several of the principles outlined by Harvey et al. (2025). Lundgren and Poell (2016), while being concerned with evaluating the quality of critical reflection, offered attending to feelings as a component to be incorporated into research evaluation, which suggests this may need to be adequately addressed within the critical reflection process.

The above principles by various authors do not necessarily fully address pedagogical or philosophical underpinnings of teaching practice, nor do they always get at the specifics of how to undertake these broad strategies in concrete ways. Potential tensions arise for implementation in practice without addressing pedagogical philosophy and concrete strategies. For example, the ‘set the scene’ principle outlined by Harvey et al. (2025) is both narrow (setting expectations, which could occur at the start of an activity or assessment) and broad (should also be applied to the whole curriculum, as an ongoing measure, underpinned by a foundation of psychological safety). While it is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss teaching philosophies, we recognise that teaching philosophies aligned to Mezirow are likely needed, such as critical pedagogy (hooks, 1994) and andragogy (Mezirow, 1981). We note the risks of mismatched teaching philosophy to implementing effective critical reflection as part of our Limitations section.

Nevertheless, the above-listed principles serve as a foundation for considering aspects of teaching critical reflection, and we have used them where relevant as a basis for our model. We therefore extend these authors’ work to offer ideas for teaching in practice and further thoughts on where additional research or discipline-based contextual work is needed.

A STEP-BASED MODEL FOR OPERATIONALISING CRITICAL REFLECTION

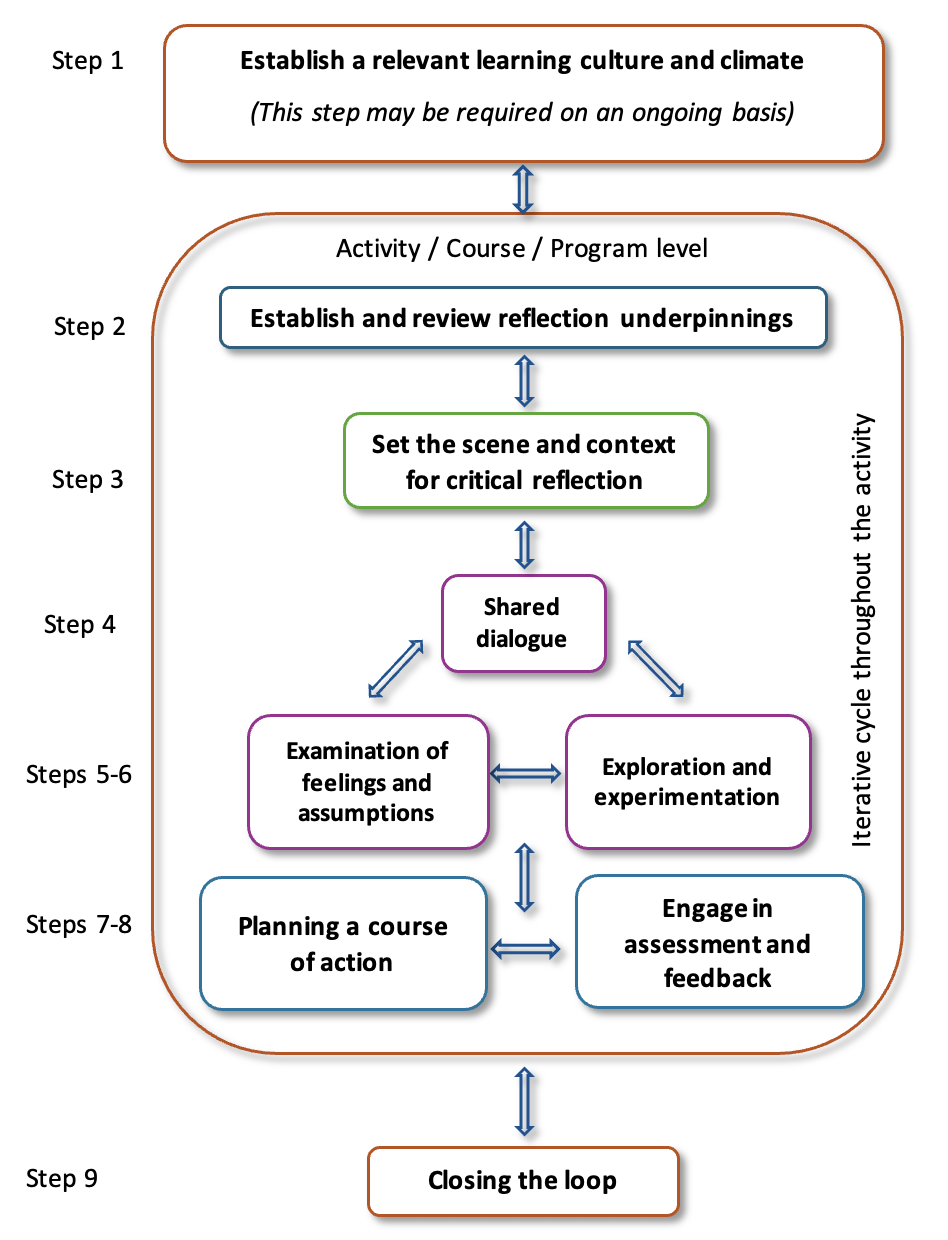

We have utilised Mezirow’s phases of transformative learning (Mezirow, 1978) and adapted and extended upon the principles of Harvey et al. (2025) to build a model that can be used in teaching practice for critical reflection toward transformative learning. Pedagogical principles from hooks’ (1994) critical pedagogy, whose work is aligned with Mezirow was also incorporated.

Our model (Figure 1) is ideally iterative and can be completed and introduced at multiple levels—e.g., these steps can be iterated per learning activity but also used to guide course-wide and programmatic teaching team planning. The first two phases in particular (Establish relevant learning culture and climate and Establish support for reflection underpinnings) should be implemented continually at micro and macro levels as they incorporate activities that are well placed to be reiterated at multiple touchpoints in a program and consistently introduced and delivered by educators and course and program coordinators (e.g., within each course, at course and program orientation activities, during mentorship where possible, etc.). Examples of relevant teaching strategies and activities, as well as examples that demonstrate ePortfolio-related practices, are also presented.

Figure 1 below represents the iterative nature of the model and how it can be implemented in practice.

Figure 1

A Step-based Model for Teaching Critical Reflection

Step 1: Establish a Relevant Learning Culture and Climate

Establish a habitually reflective, psychologically safe learning culture of shared reciprocity and shared responsibility. Ensure that reflective practice and reflexivity are part of the learning culture.

- Educators should: Set the scene regarding the need for reflexive practice within the profession and set habitual practice around reflection as a base. Set learning culture expectations for student shared responsibility (shared commitment). Devise and deliver early activities to set psychological safety. Welcome students as developing professionals (future peers) within the learning community. More broadly, seek to build a culture and climate of reflective practice within their own teaching teams.

- Students should: Recognise their role and responsibility within the learning community to build a positive and engaging culture. Commit to being present and respectful within the learning community.

- Further ideas: Encourage students to reflect on who they are as professionals in early activities, for example, via reflecting and documenting their professional philosophy. Encourage students to recognise the difference between a safe space and a comfortable space, as learning may involve discomfort (e.g., sitting with confusion or uncomfortable feelings). Incorporate activities that encourage students to build trust with peers and recognition of evaluative judgment. Educators may benefit from modelling portfolio practices both for students’ understanding and their own. For example, UNSW provides teaching staff with their own institutional ePortfolios, and many of them are publicly available to view at the myEducation Portfolio website [https://myeducationportfolio.unsw.edu.au/].

Step 2: Establish and Review the Reflection Underpinnings

Establish and support (and where relevant, evaluate) the existing level and quality of reflection happening. This ensures students are primed/ready and have established some form of content reflection to then move toward critical reflection.

- Educators should: Ensure students have at least begun to form habitual reflective practice, even at a surface level (students have undertaken reflection), and feel comfortable with reflection and reflective practice. Introduce a reflection framework as relevant. Use Lundgren and Poell (2016) to seek to evaluate and clarify the quality and appropriate depth of reflection by using a simplified Bloom’s taxonomy approach.

- Students should: Engage in regular reflection activities, use reflection models or frameworks to guide reflection, and participate in feedback to provide diagnostic and evaluative information for educators. Students should utilise study aids and supports (e.g.: academic skills resources) where required to establish good study and reflective practice habits. They should seek to be creative in how they engage with reflection to suit their learning needs (e.g. use of media) and challenge assumptions of what reflection should look like.

- Further ideas: For a sample student reflection relevant to health contexts using the What? So what? Now what? Model: Refer to University of Waterloo student Jennifer Yessis’ (2024) Health Apprenticeship portfolio and the reflections contained within the Reflective posts section. For ideas on diversity of reflection and challenging assumptions of how reflective practice should be undertaken and assessed, refer to McLellan (2021).

Step 3: Set the Scene and Context for Critical Reflection

Establish a critical incident (Fook & Gardner, 2007) or disorienting dilemma (Mezirow, 1978) that establishes a need for change and/or a need to reflect on practice. Ideally, such scenarios or problems are ones that require significant effort or systemic changes to solve. This becomes the spark for learning and a catalyst for reflection.

- Educators should: Provide an adequately complex scenario or problem, a contentious quote or issue, or a systemic complexity that acts as the critical inciting incident or disorienting dilemma to be addressed through reflection, collaborative dialogue and experimentation. Provide prompts that encourage unpacking the problem and questioning why this is a problem and for whom, and what the impacts might be (establishing the need to address the problem). Ensure students understand the context for reflection, and where possible, discuss the purpose of reflection and different types/qualities of reflection. An example of a relevant complex scenario may be the problem posed by Engeström (2000) in relation to a paediatric patient and continuity of care across teams. Such a problem could provide ideas on writing relevant case studies for specific practices.

- Students should: Engage with the scenario and reflect on their own feelings and role.

- Further ideas: Arend et al. (2021) note the need for clear framing in practice, based on comparing student and teacher expectations and perceptions of critical reflection. Ensure that appropriate contextual framing, both to the scenario and to the profession and learning outcomes, has been clarified and communicated to students. Clear framing also helps students be more comfortable when dealing with discomfort and ambiguity.

Step 4: Examination of Feelings and Assumptions

Educators and students are prepared to examine their own assumptions and feelings around the topic in a safe way. This aspect can be confronting and may require both educators and students to sit with a level of discomfort.

- Educators should: Provide space for students to work through their own feelings in a safe space (e.g. private reflection or activities, quiet time). Support ways for students to calibrate their own assumptions against others. They should recognise their own role as a peer and mentor and be prepared to be challenged by students.

- Students should: Be prepared to engage with their own feelings and assumptions and be prepared to challenge their own and the teacher’s assumptions and viewpoints where relevant.

- Further ideas: Examining and calibrating assumptions can come through undertaking simulation activities that force students to question their own expectations, or by posing a question and allowing anonymous poll responses and asking students to reflect on whether their peers responses align with their own. See Fonseka and Béres (2024) for an idea of how students may challenge educators in relation to critical reflection and assumptions of power within healthcare (social work) contexts, and how respectful shared dialogue with students and educators can occur.

Step 5: Creating Shared Dialogue and Reflective Space

Allowing opportunities for students to calibrate against and dialogue with peers is important for getting comfortable with uncomfortable feelings and to learn from others. This supports Mezirow’s phase four (recognise that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared).

- Educators should: Provide space for students to share with or calibrate their own discomfort against their peers. Provide and maintain safe spaces and environments for students to share in diverse ways (e.g.: various formats, identified vs. anonymous). Ensure that students feel they won’t be judged based on their authentic accounts. Conduct activities and prompts that support students to better understand their feelings, tease out complexity and why a problem may affect particular actors within a system more than others.

- Students should: Engage in respectful discussion that includes turn-taking, sharing curiosity, comparing ideas, and active listening where relevant. Be curious about everyday taken-for-granted experiences as well as new ones.

- Further ideas: Develop and deliver a sequential learning activity that allows students to anonymously calibrate or explore their assumptions/knowledge with their peers. Use this as a basis for peer discussion that unpacks perspectives and the problem more fully, with a view to better understanding the problem. Arend et al. (2021) note journaling and discussion as key activity types supporting dialogue. This step can be iteratively linked to examination of feelings and assumptions, and exploration and experimentation steps.

Step 6: Exploration and Experimentation

Exploration to develop potential solutions to an identified problem or consider agency and action around own role (e.g., change in values and actions). Allows for productive failure and building learning communities or interprofessional practice where relevant.

- Educators should: Devise activities that incorporate or encourage exploration (e.g.: simulations, case studies, problem-based learning, inquiry projects/reports). Implement activities that allow students to engage in risk-taking, productive failure, trial and error, discussion, and dialogic feedback. Ensure students have opportunities to undertake briefing and debriefing cycles.

- Students should: Come prepared to undertake work authentically and rigorously. Undertake relevant pre-work where expected. Commit to building a safe space/climate for others; capture notes and thoughts through the process regularly. Participate in discussions or other activities willingly while recognising role as part of a team. Students may bring reflections or reflective samples to discuss, based on their level of comfort and consent.

- Further ideas: Exploration activities may include discussion, simulation-based learning, problem-based learning activities, engaging with relevant critical theorists or Indigenous knowledges/lived experience experts, or clinical practice/simulated practice activities. ePortfolios hold benefits in supporting regular reflection and other activities to capture in-the-moment thoughts and undertake brief/debrief cycles or to capture the process of exploration and experimentation. Such documentary evidence supports students in making sense of their learning and can better support the assessment and feedback process (validation of learning).

Step 7: Planning a Course of Action

Encourages individuals to use what they have learned so far to move towards future goal setting and/or action or changed role and values. Ideally, this step is treated more as an iterative phase, combined with demonstrating action or personal/professional change.

- Educators should: Build activities that require students to reconsider how ‘what they have learned’ translates to their practice and what it means for their sense of professional role and personal values. They should also train and support students to undertake goal setting or renewed professional planning and values statements and take forward small actions or validations for themselves. At this point, educators may also wish to bring in opportunities to discuss well-being and self-care and opportunities for shared care/peer support.

- Students should: Reflect back on what they have learned and where they started, what changes in perspective to their professional and personal values have resulted, and what they can do now to take these insights with them into the professional field. For an example of student meta-reflection upon an experience and discussion of the reflective practice process, refer to Kylie Myles’s (2021) University of Waterloo CTE portfolio and the Centre for Teaching Excellence (2021) supporting video, where Kylie discusses reflection for the CTE placement experiences and portfolio.

- Further ideas: Use this as an opportunity to build ‘bookend’ activities that involve looking back and looking forward. For example, students can revisit professional values statements, look back at the original critical incident or disorienting dilemma and evaluate their mature understanding of the topic, set short-term and long-term goals, or examine areas of specialisation linked to new-found values.

Step 8: Engage in Assessment and Feedback

Devise and deliver diverse, scaffolded opportunities for student self, peer, and assessor feedback to aid building confidence, evaluative judgement, and further reflexivity.

- Educators should: Devise and deliver diverse and scaffolded opportunities for student self-, peer-, and assessor feedback at various stages in the process. Some of these should be formative or diagnostic. Ensure students are oriented to the task and requirements and the feedback process for feedback literacy. Where summative assessment is involved, consider carefully the role that marking plays in building and undermining motivation. Build rubrics or criteria that support, where possible, diverse ways of learning such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (Dave & Mitchell, 2024).

- Students should: Undertake self-assessment using relevant tools provided and engage in reflection related to change in positionality. Engage in peer review and self-review activities and engage in viewing and considering feedback and how this shapes next steps. Engage with assessor feedback with a view to action and changed practice/next steps.

- Further ideas: Incorporate student evaluative rubrics into the assessment directly, such as through ePortfolio self-assessment templates, qualitative rubrics to rate the quality of reflection, or self-reflection prompts on identity, using tools such as the Johari window. Arend et al. (2021) highlight that assessment can lead to students writing to the expectations. Consider the potential for holistic or qualitative rubrics or ungrading practices. Many ePortfolio technologies also support decoupling feedback from grades, which may support providing and asking students to engage with feedback before receiving grades.

Step 9: Closing the Loop

Post-assessment opportunities for 360-degree feedback if/where this hasn’t been adequately incorporated into the assessment process.

- Educators should: Encourage students to reflect on the process and how they feel/what they have learned/how they have changed. Gather feedback from students on what has/hasn’t worked. Use this as an opportunity to perform diagnostic and research evaluation-led activities (e.g.: gaining consent to use student work for future examples, evaluate quality of reflection and note any changes in quality, gather stories/narratives as evidence, gather feedback to note potential improvements for next teaching iteration).

- Students should: Provide useful and respectful feedback on activities that ideally is not clouded by subjectivity. Come to a looking-back process with openness regarding past assumptions and work. Document feelings and change, and make a plan for next steps or what this means in practice.

- Further ideas: If incorporating evaluation into the teaching process for research purposes, refer to Lundgren and Poell (2016) for ideas on how to evaluate the quality and type of reflection.

The model we have proposed is, at this stage, theoretical, but we hope it provides a starting point at least for educators to consider their own role and positionality in supporting critical reflection. Educators can reflect on phases of reflection and what constitutes deep critical reflection for their teaching and professional discipline contexts. Educators should also seek to locate authors who are contextually relevant to their discipline for specific ideas in practice.

LIMITATIONS

This model aims to support educators with concrete ideas about how to structure learning activities that might better move students toward deeper, critically reflective and reflexive practice, and it demonstrates where ePortfolios support such practices at micro and macro levels. While we have endeavoured to establish a step-based model, we would like to note a number of limitations in our work that also pose opportunities for further research and further work.

Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Model in Context

The evidence base for this model, and for evaluating critical reflection and transformative learning theory in practice, still has large gaps. We welcome others to utilise or evaluate this base model and conduct further research and provide feedback that challenges or extends on our work. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the model for deepening student critical reflection, we recommend using Lundgren and Poell’s (2016) framework that evaluates both type and quality of critical reflection.

Tensions and Contradictions of a Step-based Model for Critical Reflection

We recognise that a step-based model risks being implemented in a tokenistic ‘checkbox’ manner and is in some ways contradictory or antithetical to a critically reflexive process. Critical reflection as a development process takes time and will not necessarily be linear for students or individuals. ePortfolios as such may offer affordances to handling the messiness of critical reflection for both educators and students. Educators should also use judgment when implementing and refer to the first two phases regularly if and where they feel that aspects of delivery are not working.

Underpinning Philosophies and Other Preconditions

We highlight that the adoption of the framework also depends on an individual teacher’s value system and underlying teaching philosophy that he/she has, as not all teaching philosophies will align to transformative learning theory. When moving from typical content reflection (single loop learning) to critical or premise reflection (double-loop learning), the reflection becomes more values-driven. Underpinning aspects of our model rely on building psychologically safe learning cultures/spaces and critically challenging educator’s own assumptions, practices and beliefs. A teacher’s disposition and aligned teaching philosophies, as well as time available to build relevant cultures, may therefore have a central role to play. A mismatch between an educator’s philosophy and the model’s may mean an inability to successfully build environments where critical reflection (and by extension, transformative learning) can successfully occur in the classroom.

CONCLUSION

This model aims to support educators with concrete ideas about how to structure learning activities using ePortfolios that might better move students toward deeper, critically reflective practice, which in turn will improve both their ePortfolios and holistic identity. We recognise that as a theoretical framework, it requires validation and welcome educators and other researchers to utilise, test, and extend our model, thus furthering the literature on critical reflection, ePortfolios, and transformative learning theory in practice.

REFERENCES

Australian Dental Council. (2022). Professional competencies of the newly qualified dental practitioner.

https://www.adc.org.au/files/accreditation/competencies/ADC_Professional_Competencies_of_the_Newly_Qualified_Dental_Practitioner.pdf

Australian Nursing & Midwifery Federation. (2014). National Practice Standards for Nurses in General Practice. https://www.anmf.org.au/media/ouzgnqft/anmf_national_practice_standards_for_nurses_in_general_practice.pdf

Arend, B., Archer-Kuhn, B., Hiramatsu, K., Ostrowdun, C., Seeley, J., & Jones, A. (2021). Minding the Gap: Comparing Student and Instructor Experiences with Critical Reflection. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 9(1), 317-332. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.9.1.21

Bearman, M., Tai, J., Dawson, P., Boud, D., & Ajjawi, R. (2024). Developing evaluative judgement for a time of generative artificial intelligence. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(6), 893-905. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2335321

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=c805ae06-373a-34d8-b57a-536ad36440f9

Cambridge, D. (2008). Layering networked and symphonic selves. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 25(4), 244-262. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650740810900685

Centre for Teaching Excellence. (2021, 2 November). The impact of reflection on student learning: A learner’s perspective [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/28OK5dStJI8?si=H-yoGSidYKghn4ge

Clinical Excellence Commission. (2022). CEC Reflective practice workbook. Retrieved 23 April 2025 from https://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/750529/reflective-practice

Clarke, J. L., & Boud, D. (2016). Refocusing portfolio assessment: Curating for feedback and portrayal. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(4), 479-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1250664

Coleman, K. (2017). Down the rabbit hole: Lessons learned curating, presenting and submitting a digital research portfolio as PhD thesis. Owning, supporting and sharing the journey: ePortfolios Australia Forum 2017 [conference presentation]. 20–21 September, 2017. https://eportfoliosaustralia.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/ebook_eportfolioforum_2017_papers_v1_20170907.pdf\

Dave, K., & Mitchell, K. (2025). Enhancing Flexible Assessment Through ePortfolios: A Scholarly Examination. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice,22(3). https://doi.org/10.53761/wearsf41

Engeström, Y. (2000). Activity theory as a framework for analyzing and redesigning work. Ergonomics, 43(7), 960-974. https://doi.org/10.1080/001401300409143

Fonseka, T. M., & Béres, L. (2024). Professional power in social work education and practice: a process of critical reflection and learning. Social Work Education, 43(5), 1336-1353. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2023.2181329

Fook, J. (2021). Practicing Critical Reflection in Social Care Organisations (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429351501

Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2007). Practising critical reflection: a resource handbook. McGraw-Hill Education.

Harvey, M., Walkerden, G., Semple, A., McLachlan, K., Lloyd, K., & Bosanquet, A. (2025). Reflecting on reflective practice: issues, possibilities and guidance principles. Higher Education Research & Development, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2025.2463517

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress : Education As the Practice of Freedom. Taylor & Francis Group.

Hope, V. & Henderson, M. (2014). Medical student depression, anxiety and distress outside North America: a systematic review. Medical Education 48(10), 939-1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12512

Iedema, R. (2011). Creating safety by strengthening clinicians’ capacity for reflexivity. BMJ Quality & Safety, 20, i83-i86. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046714

Kitchenham, A. (2008). The Evolution of John Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory. Journal of Transformative Education, 6(2), 104-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344608322678

Lodge, J. M., Howard, S., Bearman, M., Dawson, P., & Associates. (2023). Assessment reform for the age of Artificial Intelligence. Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. https://www.teqsa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-09/assessment-reform-age-artificial-intelligence-discussion-paper.pdf

Lundgren, H., & Poell, R. F. (2016). On Critical Reflection: A Review of Mezirow’s Theory and Its Operationalization. Human Resource Development Review, 15(1), 3-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484315622735

McCarthy, A., Mitchell, K., & McNally, C. (2025). ePortfolio practice for student well-being in higher education: A scoping review. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.53761/7xwpq305

McLellan, P. N. (2021). Collecting a Revolution: Antiracist ePortfolio Pedagogy and Student Agency That Assesses the University. International Journal of ePortfolio, 11(2), 117-130. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1339426

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective Transformation. Adult Education, 28(2), 100-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171367802800202

Mezirow J. (1981). A critical theory of adult learning and education. Adult Education Quarterly, 32, 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171368103200101

Mezirow, J. (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: a guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Myles, K. (2021) CTE Senior Online Learning Assistant portfolio. Retrieved 28 July 2025 from https://app.pebblepad.ca/spa/#/public/WdczhRzqG5ynH783y5ydGdbk4y?historyId=fpgkKqXfxE&pageId=WdczhRzqG5ynH4zxH7bkrdWbwM

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia. (2016). Registered Nurse Standards for Practice. Retrieved 23 April 2025 from https://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/codes-guidelines-statements/professional-standards/registered-nurse-standards-for-practice.aspx

Polly, P. & Coleman, K. (2024, 21 June). Can ePortfolio pedagogy be shaken by AI? UNSW Education and Student experience: News and events. https://www.education.unsw.edu.au/news-events/news/can-portfolio-pedagogy-be-shaken-ai

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. (2022, 13 September). Progressive capability profile of the general practitioner: Ethical Professional at Entry. Retrieved 23 April from https://www.racgp.org.au/profile-of-a-gp/ethical-professional/entry

Rudman, A., & Gustavsson, J. P. (2012). Burnout during nursing education predicts lower occupational preparedness and future clinical performance: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(8), 988-1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.03.010

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Jossey-Bass.

Torres, J. J., & McKinley, M. (2023). From review to practice: Implementing ePortfolio Research in professional identity formation. International Journal of ePortfolio, 13(1), 1–9. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1407254.pdf

Yessis, J. (2024). University of Waterloo SLICC Workbook: Health Apprenticeship Winter 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2025 from https://app.pebblepad.ca/spa/#/public/WdczhRwjshqkzk3qz59wk3xGfr?historyId=E0QFIpe3ER&pageId=18f2b99f-f0b4-409b-911c-ad8c50fa45f4

AUTHORS

Kate Mitchell is an experienced learning designer and past teacher across multiple educational sectors (including secondary, vocational, and higher education). She currently works at the University of Melbourne supporting teaching staff to improve their teaching and assessment design, while advocating for curriculum alignment, ePortfolio practices, accessibility and inclusion, and student experience. Her research work and interests span ePortfolios, learning design, staff development and community mentorship, equity in online learning and professional identity within third space.

Email: mitchellkm@unimelb.edu.au

Dr Kashmira Dave is an experienced academic and educational specialist with over 20 years of experience in teaching, learning design, and research within Higher Education. Her work spans learning and teaching, curriculum and learning design, professional development, third space, active learning, technology integration, inclusion and ePortfolios in higher education. As a Senior Lecturer in Academic Development at the University of New England, Kashmira leads professional development initiatives, supports curriculum innovation, and oversees projects that enhance SoTL for academic staff. Kashmira is a published researcher and reviewer, her passion is advancing educational practices through evidence-based strategies and fostering community within higher education.

Email: kdave3@une.edu.au

Dr. Aslihan McCarthy is an educator and researcher with extensive experience in the higher education sector. She teaches in the social sciences and conducts research in health professions education, with a focus on student identity formation and programmatic assessment. Her academic work combines innovative pedagogy with evidence-based assessment strategies, aiming to enhance student learning and professional development in diverse educational contexts.