29 Teaching Practice Without Boundaries: ePortfolios as an Innovative Digital Solution to Assess Professional Development and Teaching Practice

Nageshwari Pam Moodley, Fatima Makda, and Reuben Dlamini

University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This chapter examines how ePortfolios can be used as an innovative digital solution to assess students’ teaching practice, thereby eradicating classroom boundaries for assessment. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted initial teacher education in South Africa, challenging the legislative mandate of 24 weeks of school-based teaching practice required by the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) policy. This unprecedented situation necessitated a reconceptualisation of traditional teaching practicums that intersect policy and digital innovations. Through digital equity and social justice lenses, we view ePortfolios as a potential platform to enable academic continuity and ongoing assessment of professional development activities. However, the abrupt transition highlighted existing digital disparities, including inadequate digital literacy, infrastructure limitations, and connectivity issues, that concern initial teacher education officials and pre-service teachers. This chapter used an integrative review methodology to synthesise empirical and non-empirical literature from between 2020 and 2025 to provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges of ePortfolios as a digital innovative solution to school-based teaching practice during crises. Content analysis employed to evaluate the 15 papers. The literature reviewed provided the advantages and challenges of ePortfolios; that addresses digital competencies and internet accessibility. ePortfolios are built on distributed architecture that overlooks virtual teaching placements was not an option as it risked delaying students’ entry into the profession. As a result, we argue that ePortfolios have the potential to contribute to unbounded teaching and learning, enable timely feedback, and offer flexible professional development. We also argue that remote teaching between lecturers and pre-service teachers serve as the basis for innovative teaching placement in the new normal and as a fundamental pillar in teaching practice without boundaries in the 21st century. The study helps conscientise policymakers to review and revise the MRTEQ policy to include alternate means of teaching practice without the boundaries of a classroom.

Keywords: ePortfolios, digital solution, professional development, teaching practice, teacher education, digital assessment, integrative review

INTRODUCTION

This chapter critically explores how ePortfolios can be used as an innovative digital solution to assess students’ teaching practice portfolios, thereby clearing boundaries for assessment at a public institution of higher learning. ePortfolios can be defined as a collection of teaching documents saved on a digital platform that shows evidence of work-integrated learning (WIL) in teacher education. It is a digital archive of visual texts, lesson plans, teaching resources, and learning activities: an organisation of teaching documents that demonstrate students’ learning experiences and accomplishments during WIL (Zhang & Tur, 2022).

The chapter is framed within the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) policy (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2015), the ecology of teaching practice, and the challenges students faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The MRTEQ policy serves as a regulatory framework for initial teacher education (ITE) programmes in South Africa, including the Bachelor of Education and Postgraduate Certificate in Education, and outlines guidelines for Work-Integrated Learning (WIL), also known as teaching practice (Moosa & Moodley, 2024; Van Heerden et al., 2020).

It mandates that ITE students complete 24 weeks of supervised school-based teaching practice over four years to qualify for registration with the South African Council of Educators. The policy also emphasizes the importance of inclusive education as part of both general and specialized pedagogical knowledge, requiring that prospective teachers be equipped to identify and address barriers to learning and apply curriculum differentiation to meet diverse learner needs (Rusznyak & Walton, 2019).

BACKGROUND

During the COVID-19 pandemic, ITE programmes struggled to meet their legislative responsibility as institutions were challenged to place students for WIL. Thus, the declaration of the pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) catalysed unprecedented changes to the traditional teaching approaches. As a result, WIL, as a vital component in ITE qualifications, was severely disrupted by the epidemic, and schools of education faced significant challenges. Schools of education coped with the school closures and physical isolation by reconceptualising the boundaries of WIL to meet the legislative requirements of the MRTEQ policy. As a result, it was necessary to find an intersection between policy and innovative digital solutions to virtually facilitate WIL. The lack of intersections between policy and innovative digital solutions accentuated the equity disparity in education. Hence, this transition, while innovative, created great trepidation on the part of ITE officials as pre-service teachers were expected to learn how to be a teacher, become integrated in a school environment, and get involved in the school community as a responsible member of a professional development community. Therefore, the changing landscape of education in the 21st century requires a system that can leverage classroom-based assessments using digital technologies.

With the omnipresent use of digital technologies and platforms, human interaction has transcended time and space (Egger & Yu, 2022), and the role of digital technologies and digital platforms has become a topic of discussion among academics, education practitioners, and policymakers. This is because the challenges faced by ITE seem to be increasingly related to digitalisation, which has an impact on the quality of education and, ultimately, threatens the long-term sustainability of equal education. WIL is critical in the preparation of teachers for effective classroom teaching and learner management and for responding to societal issues in general. To prepare effective teachers, teachers must acquire the required pedagogic content knowledge in their subjects of specialisation. In South Africa, teacher education programmes have been designed according to the policies of the Department of Higher Education and Training. The MRTEQ policy presents two main paths for becoming a qualified teacher in South Africa: a four-year Bachelor of Education degree or a three- or four-year bachelor’s degree followed by a one-year Postgraduate Certificate in Education. The MRTEQ policy provides a framework that ensures all teacher education programmes in South Africa meet a defined set of standards. The MRTEQ policy also ensures pre-service teachers are equipped with the skills, dispositions, pedagogical content, and knowledge of educational theory that contribute to making them effective in content delivery, learner management, and responding to societal issues.

It is recognised worldwide that ITE plays a significant role in supporting the production of effective, high-quality and competent teachers (Shiohira et al., 2022). However, the rising threat of digitalisation to equitable access to quality and inclusive education has become a pressing education sustainability concern that highlights the importance of digital equity. As the COVID-19 pandemic fades into history, higher education institutions are challenged to rethink university teaching (Laurillard, 2013). Rethinking ITE requires a dualistic epistemological approach to experiencing the theoretical components of the programme and the reality of teaching in complex school settings. Thus, our argument is for teaching practices without boundaries that align with the MRTEQ policy and Sustainable Development Goals 4 and 10. In the historically dominant ‘face-to-face’ model of teaching and learning, physical attendance at schools to practice is not negotiable, yet the new classrooms follow a hybrid model. The public higher education institutions in South Africa have not managed to meet the ever-increasing demands for teachers in both private and public schools. In response to this predicament, private higher education institutions have made great efforts to produce teachers to address the demand for teachers in South Africa.

It has been indicated that normal activities of teaching and learning in educational institutions, including schools, colleges, and universities worldwide, have been significantly impacted by the long-lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Aristovnik et al., 2020; Bozkurt et al., 2022; Sohrabi et al., 2021). Therefore, educational institutions are responding to the changing dynamics by adopting technology to aid teaching and learning. In this regard, educational affordances have continuously been adopted by educational institutions to reinforce teaching and learning activities and to support learners remotely. Education affordances are defined as opportunities for an educational activity that are determined and supported by perceived and actual features of an object or an environment (Xue & Churchill, 2019). Dlamini and Ndzinisa (2020) also observed that the quality of various combinations of interactions on digital platforms depends on digital capital, digital equity, and institutional capacity. Previous studies indicated that educational affordances have brought significant gains to classrooms. For example, John and Sutherland (2005, p. 406) argued that “the emergence of new digital technologies offered the possibility of extending and deepening classroom learning in ways hitherto unimagined.” In addition, Wassef and Elkhamisy (2020) argued that Google Classroom is effective in performing formative assessments and providing ongoing, timely feedback, which motivates learners and promotes their engagement. Wassef and Elkhamisy reiterated that online educational platforms boost the critical thinking skills of learners as they provide more communication networks for learners with introverted personalities. Furthermore, Dlamini (2023) stated that there is a significant transition to digital education by educational institutions, in which various digital platforms and technologies have been implemented to enable remote teaching and learning. In addition, Dlamini and Ndzinisa (2020) argued that digital education supports ubiquitous teaching and learning by creating a unique and valuable online distributed learning environment for learners. This unprecedented shift to remote teaching and digital learning raises multiple questions for ITE programmes. Hence, this integrative review research looked at the multifaceted challenges of instructional activities and teaching practices in preparation for the new schooling context. To contextualise this research through digital innovation and social justice lenses, this chapter explores the following main research question:

- How can ePortfolios contribute towards a digitally innovative solution for the professional development of student teachers without boundaries?

This main question was guided by the following two sub-questions:

- How does the MRTEQ policy address or fail to address the integration of digital tools like ePortfolios in ITE?

- What are the affordances of ePortfolios that can assist with teaching practicums?

In South Africa, the MRTEQ policy requires that students in ITE programmes complete a total of 24 weeks of school-based teaching practice under supervision over a four-year period (cite, is this the DHET source?). The teaching profession has become competitive and requires individuals to participate in extracurricular activities beyond the MRTEQ policy to develop new pedagogical skills and the right kinds of characteristics to succeed in the technology-enhanced education environment. This was more clearly recognised during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Problem Statement

During the COVID-19 pandemic, ITE programmes struggled to meet their legislative responsibility as institutions were challenged to place students for WIL (Moosa & Moodley,2024). WIL integrates disciplinary knowledge and an on-site real work environment to prepare students for professional work settings. However, the declaration of the pandemic by the WHO (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020) meant shifting to working remotely, and as a result, WIL, as a vital component of ITE qualifications, was severely disrupted by the pandemic, and schools of education faced significant challenges. As a result, it was necessary to converge the MRTEQ policy and innovative digital solutions to virtually facilitate WIL. Through digital equity and social justice lenses, ePortfolios emerged as a powerful platform to enable academic continuity, especially to assess the professional development of teachers. However, it came with complexities and challenges, such as digital inequalities, inadequate digital pedagogical knowledge, infrastructure limitations, unstable connectivity, and unstable power connectivity. Against this backdrop, there remained the legislative responsibility to produce qualified teachers with the ability to integrate different types of knowledge, practices and learning. Though ePortfolios became critical in advancing teaching practices beyond the confines of physical classrooms, it became apparent that it was necessary to overcome lack of digital competencies. Despite these issues, overlooking virtual teaching placement was not an option. Therefore, the present research sought to explore how ePortfolios can contribute toward an innovative solution to professionally develop student teachers without boundaries. To fully understand the potential of ePortfolios to address these challenges, it is essential to situate these challenges within the broader theoretical landscape and the evolving ecology of teaching practice.

THEORISING THE ECOLOGY OF TEACHING PRACTICE

In the past, teaching practice has been a theorised phenomenon in relation to face-to-face teaching and learning. However, there is a growing demand for educational opportunities, particularly for non-traditional students (Headden, 2014), and traditional students are also seeking out alternative modes of curriculum delivery (Hachey et al., 2022). The new reality of ITE presents a fundamental shift in student demographics (Headden, 2014). The technology-driven form of education is fast becoming an attractive alternative for students. Digital learning platforms, also known as learning management systems, are the bedrocks of hybrid education offerings (Dlamini & Ndzinisa, 2020). The MRTEQ policy needs to emphasise the pedagogical integration of digital technologies into the ITE institutional culture. With a new emphasis on digitalisation and a multi-disciplinary perspective on teaching methods (Dlamini & Ndzinisa, 2022), the practice of teaching must change. Paradoxically, the current ITE ‘curriculum’ favours traditional approaches to education, despite the emphasis on lifelong learning.

The digital age emphasises the significance of autonomous learning abilities, or self-regulated learning (Johnson & Davies, 2014; Kharroubi & ElMediouni, 2024; Mohanraj, 2024; Sahin Kizil & Savran, 2016); hence, our argument for ePortfolios as an innovative digital solution to assess professional development and teaching practices. The rise of lifelong learning and emphasis on self-regulated learning are disrupting the school culture, making teaching a profession in transition because of the escalating need for responsive education. Pintrich (2000) described self-regulated learning as “an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behaviour, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features of the environment” (p. 453). Technology-enhanced learning environments have provided a springboard for integrating digital learning tools to enrich both formal and informal instructional contexts (Dlamini, 2023; La Fleur & Dlamini, 2022; Pietersen, 2024).

Therefore, it is critical to make the most out of hybrid teaching or digital platforms when there is an alignment between policies and classroom practices in a variety of contexts. Zhang and Tur (2024) concluded that “e-portfolio was a crucial instrument in online education, aligning well with self-regulated learning processes” (p. 429). Up to this point, our experience in the ITE curriculum has been informed more by the perspectives of academic staff and less by the perspectives of students, especially the under-represented socio-economic group. Given the historical background of South Africa, ITE programmes should consider the diversity of the population, especially those who are concurrently studying and working. In this study, we aimed to explore and analyse the affordances of ePortfolios that can assist with teaching practicums.

In conjunction with the MRTEQ policy, ITE should close the gap between practice-based knowledge and the functional imperatives of the digital world because aligning professional development policies with the ever-changing times is crucial for achieving sustainable education growth (Moodley, 2024). In South Africa, achieving sustainable education growth is important given the substantial socio-economic disparities. Badaru and Adu (2022) stated,

In South Africa … educational institutions were confronted with the urgent need to improve their modes of online curriculums and course navigation, online examinations, increase student inclusion for remote learning, and strengthen their capacity for ICT [information and communication technology] solutions in the time of crises (p. 67).

Given the rise of hybrid teaching and digital platforms, the responsibility to offer alternative WIL should be driven by a new revised national policy. In response to these challenges and the growing demand for flexible, digitally supported teacher education, national policy shifts, such as the revision of the MRTEQ policy, have become increasingly significant.

THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS FOR TEACHER EDUCATION QUALIFICATIONS POLICY

The Department of Higher Education and Training in South Africa has adopted policy interventions through the revision of the MRTEQ policy (Shiohira et al., 2022). In South Africa, reviews of ITE programmes revealed inconsistent tendencies, challenges with less pedagogical content knowledge, and some programmes lacking the required subject content knowledge for teachers. The number of higher educational institutions that continue to strengthen the production of highly qualified teachers has significantly reduced. In South Africa, studies indicated that for previously disadvantaged universities, the entry requirements for ITE have remained below those of other professions at higher education institutions for more than a decade (Cloete, 2014; Van Broekhuizen, 2016; Gumede, 2020). Moreover, research also indicated that there is consistently poor delivery of practical teaching components of ITE (Shiohira et al., 2022). Shiohira et al. (2022) stated that there is a high demand for high-quality teachers in South Africa because of the changing dynamics in the demographic profiles of teachers, teacher retention, and the throughput rate of teacher graduates from universities.

In contrast to Shiohire et al. (2022), Green et al. (2014) argued that the demand for teachers in the public sector in South Africa continues to increase and that it is a challenge to meet this demand. In addition, universities require financial resources to enhance the production of qualified teachers to meet the school demands. Shiohira et al. (2022) argued that fewer teacher internship programmes operate in rural provinces of South Africa. Therefore, there is a critical need to match the ever-increasing demands for teachers in South Africa, which only produces half of the required teachers for schools. Therefore, this paper argues that it is necessary to address this increased demand for teachers by adopting technology-enabled approaches, which include ePortfolios in teacher training at universities. While ITE programmes continue to maintain the traditional approaches to shape student teachers and prepare them for actual teaching in schools, it is critical to acknowledge the heterogeneity of learners and socio-economic status to usher in strategic changes in teaching and learning. This is despite numerous emerging technological changes that must be adopted in educational institutions. In addition, there is an increasing number of newly trained teachers who are joining the labour market, which is evolving with technological changes and new shifts in teaching methodologies.

Ndebele et al. (2024) stated that new teachers struggle with adjustment challenges in schools, including the behavioural, societal, and global issues they face in their work environments. In Africa, there is approximately a 20% growth per annum in the public higher education sector. To address the ever-increasing demands for high-quality teachers, private higher education institutions play a significant role by providing teacher training opportunities for potential teachers and by providing job opportunities (Mboyonga, 2025). In South Africa, there remains an increasing demand for teachers for public schools. In 2022, approximately 1.1 million students were enrolled in South Africa’s public universities, while 219 000 placement spaces were available in private higher education institutions (Singh & Tustin, 2022). Singh and Tustin (2022) argued that several challenges affect the higher education sector in South Africa, including an increase in student enrolments, budget constraints, assessment practices, and the effective delivery of teaching and learning. To address these challenges, universities are increasingly adopting the use of various technologies to enable learning and teaching.

Other research also indicated that ePortfolios promote “personal,” lived, and self-directed learning with 21st-century skills because they are evidence-based and flexible (Arnold-Garza, 2014). In addition, ePortfolios are regarded as useful to empower learners to lead to more and intensive reflection, collaboration, and active engagement in the teaching and learning process (van Wyk, 2017). Furthermore, Arnold-Garza (2014) argued that ePortfolios is useful for supporting formative and summative assessments for learners in educational institutions. However, there seems to be a dearth of literature on bringing the advantages of technology into the classrooms. Therefore, the present research sought to explore how ePortfolios can contribute to an innovative solution to professionally develop student teachers without boundaries. Integrating ePortfolios as an alternative to assessing WIL is critical to achieving social justice by avoiding further delaying students from entering professional spaces to practice as teachers.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Through digital equity and social justice lenses, we viewed ePortfolios as powerful platforms to enable academic continuity and assess ongoing professional development activities.

Social justice is recognised as a fundamental value (United Nations, 2006) “to a state of fairness, moderation, and equality in the distribution of rights and resources in society” (Aanestad et al., 2021, p. 1). Davis et al. (2007) defined digital equity as “equal access and opportunity to digital tools, resources, and services to increase digital knowledge, awareness, and skills” (p. 152), which demonstrates the state of fairness to which the United Nations refers. The integration of ePortfolios in WIL is complex and multifaceted and requires the following:

A multidimensional approach that could engage the different realms of the phenomena, such as the economic, socio-cultural, and political spheres of adult learners’ lives, mediated by factors such as access, motivation, skills, and usage in the context of the lived experiences of the learners. (Chundur, 2017, p. 1387)

However, ePortfolios come with complexities and challenges, such as digital inequalities, inadequate digital pedagogical knowledge, infrastructure limitations, unstable connectivity, and unstable power connectivity. Against this backdrop, there remains the legislative responsibility to produce qualified teachers with the ability to integrate different types of knowledge, practices, and learning. Two principles of social justice guided our argument, namely digital social justice (Rawls, 1999) and social and economic inequalities (Chundur, 2017). In 2020, digital, social and economic inequalities derailed those who were already disadvantaged and could have been easily excluded from completing the MRTEQ WIL requirement because of the unequal distribution of resources. Therefore, the intersection of policy and digitalisation must be addressed because “unaddressed digital inequality would progressively worsen structural inequalities that exist” (Chundur, 2017, p. 1387). The intersection of policy and digitalisation is critical to revolutionise traditional educational hierarchical structures and paradigms (Dlamini, 2025). To put this into perspective, the extent to which ITE programmes adopt digitalisation depends on national policies.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

This chapter used an integrative review methodology, as outlined by Souza et al. (2010), to synthesise available literature and provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and affordances of ePortfolios as a digital innovative solution for school-based teaching practice during crises. This approach was chosen because it allows for the inclusion and synthesis of diverse methodologies, including empirical and non-empirical studies, to address the complexity of the phenomenon under investigation (Souza et al., 2010). The review was structured following the six phases of the integrative review process to ensure a systematic and rigorous approach to knowledge synthesis.

Phase 1: Preparing the Guiding Question(s)

The research questions discussed in the Introduction and Background section of the chapter guided the search.

Phase 2: Searching or Sampling Literature

The literature search was conducted systematically across multiple electronic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Our primary literature search was conducted using the Scopus database due to its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed literature, strong indexing, and citation analysis tools, which are crucial for ensuring the quality and relevance of the sources. We supplemented our search with the search strings on Google Scholar to identify highly cited works, emerging research, and additional peer-reviewed sources. Furthermore, we reviewed relevant policy documents to provide a well-rounded and practical perspective on the subject matter, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of both academic discourse and real-world implications.

The search strategy involved a combination of keywords related to ePortfolios as an innovative digital solution. These keywords included ‘initial teacher education’, ‘teaching practice’, ‘school-based practicum’, ‘COVID-19’, ‘pandemic’, ‘digital solutions’, ‘affordances’, ‘ePortfolios’, ‘virtual learning’, and ‘South Africa’, and we used variations and combinations of Boolean operators (AND/OR). A preliminary search was conducted to refine keywords and identify relevant indexing terms.

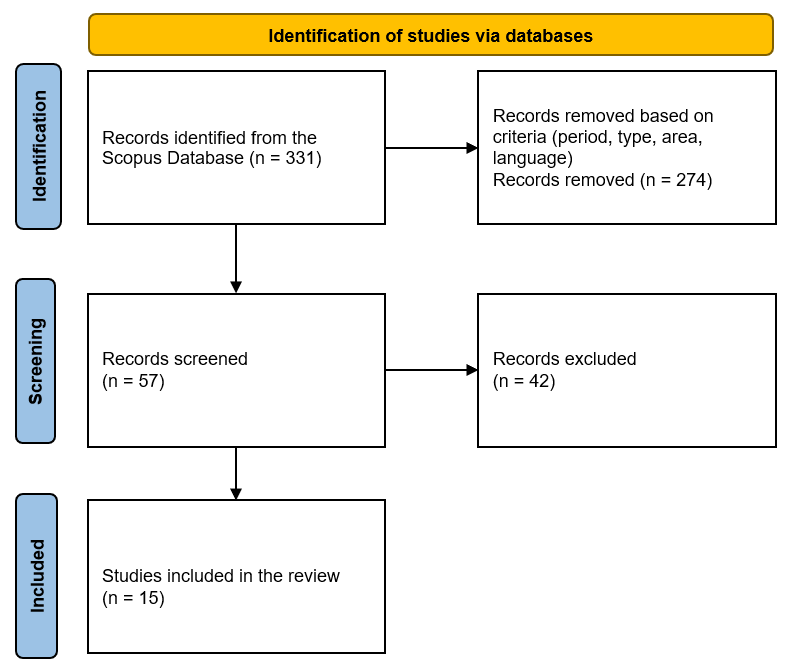

The search and selection process strictly adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021) to ensure transparency and replicability. A PRISMA flow diagram detailing the entire search and screening process is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram showing the literature search and screening process

The process began with an initial search that yielded 331 publications. Criteria were applied on the year, document type, area and language to refine the records. The criteria included the period under review of 2020-2025, the document type of journal articles, the area of social sciences and humanities and the language limited to English. 274 records were excluded. The initial screening of the remaining 57 articles was done in Scopus, based on the titles and abstracts of the articles. 42 articles were excluded based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria described in Table 1. The full-text articles of the remaining 15 studies were then downloaded and assessed.

Table 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (created by Authors)

|

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Studies published between 2020 and 2025 |

Studies published before 2020 |

|

Peer-reviewed articles |

Literature reviews, grey literature, book chapters |

|

Studies published in English |

Studies published in a non-English language |

|

Studies about ePortfolios, ITE, professional development, teaching practice, e-portfolio for assessment and reflective practice |

Studies not directly addressing the research questions |

|

Studies published in South Africa or within the South African Context |

Outside the context of South Africa |

The authors independently conducted the screening and full-text assessment, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Phase 3: Data Collection and Evaluation

A data extraction form was developed to systematically gather relevant data from each of the 15 included studies. The information extracted included the authors, year of publication, country/context of the study, methodology, and key findings relevant to the research questions.

Phase 4: Critical Analysis of the Studies Included

Each selected study underwent a critical, expert-based appraisal conducted independently by two of the authors to assess its methodological rigour and relevance. The appraisal was guided by a set of criteria based on the authors’ collective expertise, which included assessing the clarity of the research design, the direct relevance of the findings to the chapter’s guiding questions, and the overall trustworthiness of the study’s claims. For empirical studies, we evaluated the evidence supporting their claims; for theoretical papers, we assessed the logical construction of the arguments. Any discrepancies between the independent appraisals were resolved through discussion with the third author until a consensus was reached. The extracted data were synthesised using a qualitative approach. This phase involved thematic analysis to identify common themes and patterns across the selected studies.

Phase 5: Discussion of Results

The discussion of the analysis specifically focused on identifying the challenges and affordances of ePortfolios, as well as the gaps in existing literature. The findings were then grounded theoretically by relating them to the MRTEQ policy.

Phase 6: Presentation of the Integrative Review

The presentation aligns with the reporting standards of the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021) to ensure that all essential components of the review process and its findings are reported transparently. The findings and their implications are discussed across the various sections of this chapter.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

This section presents the discussion of findings that are based on the integrative literature review process.

The Profile for Initial Teacher Education in South Africa

ITE in South Africa outlines the essential knowledge, skills, and dispositions required for newly qualified teachers (Geduld & Sathorar, 2016). It is guided by the MRTEQ policy, which defines the standards for all ITE programmes. ITE programmes in South Africa are designed to ensure pre-service teachers are prepared to deliver effective instruction across diverse classrooms (Moosa, 2018; Moosa & Moodley, 2024). The programmes focus on equipping pre-service teachers with essential pedagogical content knowledge specific to their subjects and on integrating disciplinary knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, practical knowledge, fundamental knowledge, and situational knowledge (Geduld & Sathorar, 2016; Department of Higher Education and Training, 2015). This aims to ensure teachers are well-prepared for effective classroom instructional delivery, classroom management, assessment, and learner management and to address broader societal issues in order to promote a coherent and high-quality teaching profession.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Teaching Practice

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted ITE programmes and teaching practicums in South Africa, particularly the crucial component of teaching practice for pre-service teachers. The national lockdown and school closures directly challenged the legislative requirement, as mandated by the MRTEQ policy, for extensive supervised school-based practicums. Traditional models of physical placement, direct supervision, and in-person assessment became largely unfeasible, forcing rapid, widespread adaptations, which were often digital solutions to virtually facilitate WIL. A significant shift to remote learning occurred across universities that necessitated the adoption of online platforms to continue ITE activities (Williams et al., 2022). Some higher education institutions adopted ePortfolios and online platforms to maintain academic continuity and assess professional development. This transition exposed and exacerbated existing digital inequalities, highlighting both the potential and limitations of technology as socio-economic disparities, unreliable internet, and load shedding presented considerable barriers for many educators and students (Theodorio et al., 2024). Teaching practicums, fundamental for hands-on experience, were severely disrupted by school closures (Williams et al., 2022). The implementation of rotational attendance further limited teaching time and continuity for pre-service teachers (Mtande & Ross, 2024). Despite these challenges, educators demonstrated remarkable resilience and innovation by using various online tools to maintain engagement (Naidoo, 2024). It was imperative to produce qualified teachers, and therefore, making virtual placements and adopting other digital solutions like ePortfolios became necessary.

Affordances of ePortfolios for Teaching Practice Without Boundaries

ePortfolios can enhance teaching practice in ITE by providing tools for reflection (Carl & Strydom, 2017; Hizli et al., 2024), self-representation (Oakley et al., 2014), and collaborative learning (Michos & Petko, 2024). They also foster continuous professional development by promoting self-directed learning, lifelong learning, critical thinking, and reflective practices, which are all essential for ongoing teacher growth (Mawela et al., 2023; Modise & Mudau, 2023). Their digital nature ensures accessibility that is independent of time and place, making them flexible for students and lecturers (Michos & Petko, 2024). Reflective practice enables pre-service teachers to document, analyse, and learn from their teaching experiences and strategies. This cultivates the critical thinking and self-assessment skills necessary for continuous professional growth (Carl & Strydom, 2017).

Beyond reflection, ePortfolios assist with documentation and evidence collection. They enable pre-service teachers to compile and present tangible evidence of their developing teaching competencies and achievements, effectively acting as dynamic digital CVs that improve their marketability to possible employers because their skills and achievements are easily shareable in a digital format (Mawela et al., 2023; Oakley et al., 2014). This structured approach to documenting progress is invaluable for both personal self-evaluation and formal assessment processes (Kabilan & Khan, 2012). Their accessibility and flexibility are further demonstrated by being digital, which means they can be accessed anywhere and anytime with mobile devices, even facilitating real-time documentation during teaching practicums (Michos & Petko, 2024). Moreover, ePortfolios foster collaboration and feedback by enabling peer and mentor interaction to enrich the learning experience and promote the development of personal learning networks for lifelong learning (Michos & Petko, 2024; Oakley et al., 2014).

ePortfolios demonstrably lead to enhanced learning outcomes by promoting self-monitoring and the sharing of learning experiences to help students identify their strengths and areas that need development (Yang et al., 2023). They also increase engagement and participation through multimedia integration to make learning more dynamic (Michos & Petko, 2024). For pre-service teachers, ePortfolios support professional development by providing a mechanism to reflect on and improve teaching strategies (Lygo-Baker & Hatzipanagos, 2014), while also developing crucial information and communication technology and pedagogical skills. Within higher education institutions, ePortfolios can streamline processes for accreditation by providing comprehensive documentation of teaching quality and student outcomes, thereby aligning teaching, learning, and assessment practices (Yang et al., 2023).

Despite the affordances of ePortfolios, challenges do exist. Technical issues like unreliable internet connections and load shedding, a pertinent concern in the context of South Africa, can hinder its effective use (Chisango, 2024; Majola & Mudau, 2022). Furthermore, the time commitment for creating and maintaining ePortfolios can be substantial for both students and teachers. To maximise the effective use of ePortfolios, several strategies must be considered, and there must be a constructive alignment between learning, teaching, and assessment practices to fully integrate ePortfolios (Biggs, 1996; Yang et al., 2023). Designing tasks that scaffold student learning progress and provide sustained support is also important (Yang et al., 2023). Finally, investment in technical support and professional development and training for both students and lecturers is essential to ensure they have the necessary competencies to effectively integrate ePortfolios into teaching and learning (Mudau & Modise, 2022). The affordances of ePortfolios and structural support present a compelling nexus for exploring alternative teaching practices.

Reforming Teaching Practice

There is evidence that structural support, the longstanding belief that face-to-face and on-site teaching practices are the only options, is flawed, given the characteristics of digital learning environments. The distinct characteristics of digital learning environments include “accessibility, flexibility, interactivity, and multimedia integration” (Sreejana et al., 2024, p. 114), and these characteristics enable multimodal teaching and learning. Importantly, digital learning environments leverage digital technologies to support remote teaching and enhance learners’ learning experiences. Remote teaching and engagement between lecturers and pre-service teachers serve as the basis for innovative teaching placement in the new normal and are a fundamental pillar in teaching practice without boundaries.

The balance between innovation and digitalisation is the impetus behind the transition to alternative teaching experiences, or WIL. The alternative teaching practice is an interaction between pre-service teachers, digital innovation, schools, ITE lecturers and policy that is aimed at advancing inclusion. While these interactions are critical, policy should enable digital inclusion and inclusive frameworks to provide structure and advance equity. Pre-service teachers should be prepared for the vast landscape of digital resources to unlock multimodal teaching and learning in order to cultivate digital pedagogies, which are the skills needed in the contemporary classroom. There have been unprecedented alterations to every aspect of our lives, and recirculation is not an option in these times of change. However, for the most part, those with the loudest voices in the room continue to stifle the transformation of ITE, and ‘brick and mortar’ classrooms continue to dominate the professional development and practice of teaching.

Having experienced the pandemic and service delivery protests that limit face-to-face and on-site teaching practices, it must be acknowledged that there is a need for alternative approaches that guarantee intellectual rigour. After the pandemic, it was clear that there is a need to relook at how teachers are prepared, and as such, there is a need for a fundamental shift to the new realities of schooling. The growing population of non-traditional students in schools, overcrowding, academically unprepared students, and diversity in classrooms indicate the need for new approaches to ITE to improve access, unlock lifelong learners, and improve learners’ attainment. As knowledge work becomes globally ubiquitous and education is implemented for academically unprepared students, we ought to explore alternative formats and inform policies through empirical evidence. In recognition of the special needs of different groups and the era we live in, we provided a comprehensive argument for alternative teaching experiences without boundaries.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the significance of technical support, professional development opportunities, and digital competencies cannot be overlooked. Our research started with a systematic review of the scholarly literature related to MRTEQ policy, school-based teaching practice during crises, ePortfolios as a digital innovative solution for alternative teaching practice, and lastly, the affordances of ePortfolios. ePortfolios are invaluable tools for enhancing student learning and professional development in teaching practice. They serve as dynamic repositories for authentic evidence of teaching, learning, and professional development, allowing pre-service teachers to collect teaching materials like lesson plans, teaching videos, reflective journals, and feedback from lecturers and mentoring in-service teachers. The digital compilation of ePortfolios goes beyond a static paper portfolio by offering multimodal documentation. ePortfolios can also act as effective assessment tools, as they enable comprehensive, standards-based evaluation of competencies required for the Bachelor of Education qualification, such as those outlined by the MRTEQ policy.

However, their successful integration requires careful consideration of the inherent structural and systemic barriers in the context of South Africa. Digital equity requires special attention to ensure no pre-service teachers are excluded. Although the challenge of digital inequalities exists, the affordances of ePortfolios, such as facilitating unbounded teaching and learning, offering flexible assessment, enabling timely feedback, supporting deep reflection, and providing evidence-based assessment, make them invaluable for teaching practice without boundaries and the professional development of pre-service teachers. Regardless of the affordances of ePortfolios, ITE programmes must recognise the critical link between technology professional development and classroom practice, and therefore, they must create opportunities for future teachers to access and apply digital technologies in their professional learning communities.

REFERENCES

Aanestad, M., Kankanhalli, A., Maruping, L., Pang, M. S., & Ram, S. (2021). Digital technologies and social justice. MIS Quarterly, 17(3), 515–536.

Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 8438.

Arnold-Garza, S. (2014). The flipped classroom teaching model and its use for information literacy instruction. Communications in Information Literacy, 8(10), 7–22.

Badaru, K. A., & Adu, E. O. (2022). Platformisation of education: An analysis of South African universities’ learning management systems. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 7(2), 66–86.

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364.

Bozkurt, A., Karakaya, K., Turk, M., Karakaya, Ö., & Castellanos-Reyes, D. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on education: A meta-narrative review. TechTrends, 66(5), 883–896.

Carl, A., & Strydom, S. (2017). e-Portfolio as reflection tool during teaching practice: The interplay between contextual and dispositional variables. South African Journal of Education, 37(1), 1–10.

Chisango, G. (2024). Exploring the effectiveness of ePortfolios in a first-year undergraduate Project Management course. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 8(3), 25–43.

Chundur, S. (2017, March). Digital equity through a social justice lens: A theoretical framework. In Society for information technology & teacher education international conference (pp. 1385–1393). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. (2020) WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. Mar 19;91(1):157-160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. PMID: 32191675; PMCID: PMC7569573.

Cloete, N. (2014). The South African higher education system: Performance and policy. Studies in Higher Education, 39(8), 1355–1368.

Davis, T., Fuller, M., Jackson, S., Pittman, J., & Sweet, J. (2007). A national consideration of digital equity. International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE).

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2015). National Qualifications Framework Act (67/2008): Revised policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications. Government Gazette, 596(38487).

Dlamini, R. (2023). Interactivity, the heart and soul of effective learning: The interlink between internet self-efficacy and the creation of an inclusive learning experience. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.20853/37-2-5105

Dlamini, R. (2025, March). Implementation of South Africa’s Education Policy in ICT: Through an access and equity-oriented lens. In Society for information technology & teacher education international conference (pp. 1598–1606). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Dlamini, R., & Ndzinisa, N. (2020). Universities trailing behind: Unquestioned epistemological foundations constraining the transition to online instructional delivery and interactivity. South African Journal of Higher Education 34(6), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.20853/34-6-4073

Dlamini, Reuben, & Rekai, Zenda. (2022). Guest editorial: Digital education and online learning to achieve inclusivity and instructional equity (Part A). South African Computer Journal, 34(2), ix-xiii. https://doi.org/10.18489/SACJ.V34I2.1185

Egger, R., & Yu, J. (2022). A topic modeling comparison between LDA, NMF, Top2Vec, and BERTopic to demystify Twitter posts. Frontiers in Sociology, 7, 886498.

Geduld, D., & Sathorar, H. (2016). Humanising pedagogy: An alternative approach to curriculum design that enhances rigour in a B.Ed. programme. Perspectives in Education, 34(1), 40–52.

Green, W., Adendorff, M., & Mathebula, B. (2014). “Minding the gap?” A national foundation phase teacher supply and demand analysis: 2012–2020. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 4(2), 1–23

Gumede, V. (2020). Higher education in post-apartheid South Africa: Challenges and prospects. Tertiary institutional transformation in South Africa revisited, 2020. https://vusigumede.com/content/2021/AUG%202021/Academic%20Paper%201.pdf

Hachey, A. C., Conway, K. M., Wladis, C., & Karim, S. (2022). Post-secondary online learning in the US: An integrative review of the literature on undergraduate student characteristics. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 34(3), 708–768.

Headden, S. (2014). Beginners in the classroom: What the changing demographics of teaching mean for schools, students, and society. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Hizli Alkan, S., Bradfield, K., & Fraser, S. (2024). Prospective teachers’ views and experiences with ePortfolios. Reflective Practice, 25(6), 767–783.

John, P., & Sutherland, R. (2005). Affordance, opportunity and the pedagogical implications of ICT. Educational Review 57(4), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910500278256

Johnson, G., & Davies, S. (2014). Self-regulated learning in digital environments: Theory, research, praxis. British Journal of Research, 1(2), 1–14.

Kabilan, M. K., & Khan, M. A. (2012). Assessing pre-service English language teachers’ learning using ePortfolios: Benefits, challenges and competencies gained. Computers & Education, 58(4), 1007–1020.

Kharroubi, S., & ElMediouni, A. (2024). Conceptual review: Cultivating learner autonomy through self-directed learning & self-regulated learning: A socio-constructivist exploration. International Journal of Language and Literary Studies, 6(2), 276–296.

La Fleur, J., & Dlamini, R. (2022). Towards learner-centric pedagogies: Technology-enhanced teaching and learning in the 21st century classroom. Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal), (88), 4–20.

Laurillard, D. (2013). Rethinking university teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. Routledge.

Lygo-Baker, S., & Hatzipanagos, S. (2014). Creating an authentic space for a private and public self through ePortfolios. In V. Wang (Ed.), Advanced research in adult learning and professional development: Tools, trends, and methodologies (pp. 197–223). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

Majola, M. X., & Mudau, P. K. (2022). Lecturers’ experiences of administering online examinations at a South African open distance e-learning university during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 8(2), 275–283.

Mawela, A. S., Van Wyk, M. M., & Dreyer, J. (2023). The use of technology to enhance the high-quality assessment of ePortfolios in institutions of higher learning. In Z. Motsa, T. Meyiwa, & L. Lalendle (Eds.), Fostering diversity and inclusion through curriculum transformation (pp. 229–253). IGI Global.

Mboyonga, E. (2025). Widening university access and participation in the Global South. Using the Zambian context to inform other developing countries. Routledge.

Michos, K., & Petko, D. (2024). Reflection using mobile portfolios during teaching internships: Tracing the influence of mentors and peers on teacher self-efficacy. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 33(3), 291–311.

Modise, M. P., & Mudau, P. K. (2023). Using ePortfolios for meaningful teaching and learning in distance education in developing countries: A systematic review. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 71(3), 286–298.

Mohanraj, S. G. (2024). Defining the potentials of self-regulated learning through digital environments: A theoretical perspective. In S. G. Mohanraj, & B. Arokia Lawrence Vijay (Eds.), Transforming education for the 21st century-Innovative teaching approaches (pp. 110). OrangeBooks Publication.

Moodley, N. (2024). Teaching practice for resilience during Covid-19 at a higher education institution. Journal of Education Studies, Special Edition, (2), 281–304

Moosa, M. (2018). Promoting quality learning experiences in teacher education: What mentor teachers expect from pre-service teachers during teaching practice. The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning, 13(1), 57–68.

Moosa, M., & Moodley N. P. (2024). Preparing pre-service teachers for teaching practice: Insights from mentor teachers in Johannesburg. Africa Education Review, 20(1–2), 55–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2024.2347236

Mtande, N., & Ross, E. (2024). Perceived psychosocial effects of COVID-19 on the teaching realities of Foundation Phase educators in selected rural Quintiles 1 to 3 schools in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 44(3). https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v44n3a2325

Mudau, P. K., & Modise, M. P. (2022). Using ePortfolios for active student engagement in the ODeL environment. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 21, 425–438.

Naidoo, R. C. (2024). From technophobia to techno confidence: Integration of iPad software applications in teacher training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education Research. Academic Conferences and Publishing.

Ndebele, C., Marongwe, N., Ncanywa, T., Matope, S., Ginyigazi, Z., Chisango, G., Msindwana, P. N., & Garidzirai, R. (2024). Reconceptualising initial teacher education in South Africa: A quest for transformative and sustainable alternatives. Interdisciplinary Journal of Education Research, 6, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.38140/ijer-2024.vol6.07

Oakley, G., Pegrum, M., & Johnston, S. (2014). Introducing ePortfolios to pre-service teachers as tools for reflection and growth: lessons learnt. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(1), 36–50.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pietersen, D. (2024). Pedagogy of care in online teaching and learning environments at tertiary institutions through the eyes of Freire. Perspectives in Education, 42(2), 1–14.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451-502). Academic Press.

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice (rev. ed.). Harvard University Press.

Rusznyak, L., & Walton, E. (2019). Inclusive education in South African initial teacher education programmes. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355493072

Sahin Kizil, A., & Savran, Z. (2016). Self-regulated learning in the digital age: An EFL perspective. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language), 10(2), 147–158.

Shiohira, K., Lefko-Everett, K., Molokwane, P., Mabelle, T., Tracey-Temba, L., & McDonald, Z. (2022). Training better teachers: An implementation brief for improving practice-based initial teacher education. JET Education Services.

Singh, D., & Tustin, D. (2022). Stakeholder perceptions and uptake of private higher education in South Africa. International Journal of African Higher Education, 9(1), 21–52. https://doi.org/10.6017/ijahe.v9i1.15231

Sohrabi, C., Mathew, G., Franchi, T., Kerwan, A., Griffin, M., Soleil C Del Mundo, J., Ali, S. A., Agha, M., & Agha, R. (2021). Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on scientific research and implications for clinical academic training–a review. International Journal of Surgery, 86, 57–63.

Souza, M. T. D., Silva, M. D. D., & Carvalho, R. D. (2010). Integrative review: What is it? How to do it?. Einstein (São Paulo), 8, 102–106.

Sreejana, S., Mohanraj, S. G., & Hema, R. (2024). Integrating language learning and problem-based learning in engineering education: A promising approach. Journal of Engineering Education Transformations, 37(IS2), 343–347.

Theodorio, A. O., Waghid, Z., & Wambua, A. (2024). Technology integration in teacher education: Challenges and adaptations in the post-pandemic era. Discover Education, 3(1), 242.

United Nations. Division for Social Policy. (2006). Social justice in an open world: The role of the United Nations. United Nations Publications.

Van Broekhuizen, H. (2016). Graduate unemployment, Higher Education access and success, and teacher production in South Africa [Doctoral dissertation]. Stellenbosch University.

Van Heerden, S., Sayed, Y., & McDonald, Z. (2020). Student teachers’ views of their experiences in a Bachelor’s programme. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 10(1), a749. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v10i1.749

van Wyk, M. M. (2017). Exploring student teachers’ views on eportfolios as an empowering tool to enhance self-directed learning in an online teacher education course. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(6), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2017v42n6.1

Wassef, R., & Elkhamisy, F. (2020). Evaluation of a web-based learning management platform and formative assessment tools for a Medical Parasitology undergraduate course. Parasitologists United Journal, 13(2), 99–106.

Williams, T., Sayed, Y., & Singh, M. (2022). The experiences of teacher educators managing teaching and learning during times of crises at one initial teacher education provider in South Africa. Perspectives in Education, 40(2), 69–83.

Xue, S., & Churchill, D. (2019). A review of empirical studies of affordances and development of a framework for educational application of mobile social media. Educational Technology Research & Development, 67(5), 1231–1257.

Yang, M., Wang, T., & Lim, C. P. (2023). ePortfolios as digital assessment tools in higher education. In Learning, design, and technology: An international compendium of theory, research, practice, and policy (pp. 2213–2235). Springer International Publishing.

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2024). A systematic review of e-portfolio use during the pandemic: Inspiration for post-COVID-19 practices. Open Praxis, 16(3), 429–444.

AUTHORS

Dr Nageshwari Pam Moodley is a lecturer in the Curriculum division and the Academic Head for teaching practice at the Wits School of Education. She holds a PHD degree in Education Leadership and Management that focussed on curriculum decolonization and her Master’s degree focused on Professional development of teachers in ICT in rural schools. Her current research trajectory changed to suit teacher education with the incorporation of virtual reality. In her current research, she is focusing on the use of immersive virtual reality headset to train student teachers for 21st century teaching within the STEM subjects.

Email: pam.moodley1@wits.ac.za

Dr Fatima Makda is an Associate Lecturer in the Science and Technology Division at the Wits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand. She holds a PhD from Wits, focusing on building virtual teaching and learning ecosystems that promote equitable digital education. Her research interests lie at the intersection of education and technology, with a focus on digital pedagogies, transformation, and access. Her work explores how to create accessible, sustainable education in diverse contexts. Dr Makda has co-authored journal articles, book chapters, and conference papers, and is actively involved in community and educational initiatives promoting equity in education. Through her teaching and research, she contributes to the discourse on leveraging digital innovation for inclusive education systems. She describes herself as a lifelong learner and a professional committed to making a meaningful difference.

Email: Fatima.makda@wits.ac.za

Professor Reuben Dlamini is an Associate Professor in Educational Information and Engineering Technology at the University of the Witwatersrand. His research focus cuts across multiple disciplines Computer Science, IT and Education, and involves implementation and evaluation of complex digitalisation and pedagogical integration of ICT interventions in education to improve access to quality education and reduce educational inequalities in resource-constrained contexts.

Email: Reuben.Dlamini@wits.ac.za