28 Building Digital Resilience Through ePortfolios in Mathematics Teacher Education

Zaheera Jina-Asvat and Lawan Abdulhamid

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This chapter explores how ePortfolios reconceptualised in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, support the development of digital resilience and deepen conceptual understanding among pre-service mathematics teachers (PSTs) within hybrid learning environments. Specifically, the chapter focuses on how ePortfolios can support PSTs in confronting and addressing persistent misconceptions about the equal sign as a relational construct. By engaging in iterative reflection, video-based lecturer critique, and collaborative lesson redesign, PSTs used the ePortfolio not only as a digital tool but as a dynamic mediational tool that provides reflective space to deepen their mathematical understanding, regulate emotional responses, and track pedagogical growth. Drawing on cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) and employing a change laboratory (CL) methodology, the study involves 115 second-year PSTs at a South African university who participated in a five-phase intervention involving lesson design, lecturer video critique, reflection, revision, and ePortfolio documentation. The findings revealed significant shifts in participants’ conceptual understanding of the equal sign as equivalence, enhanced capacity to engage in dialogic feedback, and the emergence of more reflective professional identities. The study concludes that when integrated into structured interventions, ePortfolios can foster expansive learning and digital resilience by enabling PSTs to navigate critique, correct misconceptions, and curate their own developmental trajectories. This research contributes to reimagining teacher education for uncertain futures, positioning ePortfolios as a powerful tool for resilience, transformation, and professional becoming in a digitally mediated environment.

Keywords: Digital Resilience, ePortfolio, Mathematics, Pre-service Teacher Education

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly disrupted teacher education, catalysing an urgent shift toward hybrid and remote instructional models. This transformation compelled institutions to reassess not only the delivery of content but also how to support PSTs in developing critical competencies, such as effective teaching, reflective practice, and professional identity, within a digitally mediated environment. One of the most significant yet underexplored outcomes of this disruption has been the rise of ePortfolios as a mediational tool for digital resilience—enabling PSTs to reflect, adapt, and thrive in a digital world (Ciolacu, Rachbauer & Hansen, 2022).

Prior to the pandemic, ePortfolios were primarily used for assessment or presentation. However, in the post-COVID context, these tools have been reimagined as dynamic learning environments that support asynchronous reflection, multimodal engagement, and identity development (Foreman-Brown, Fitzpatrick & Twyford, 2023). Within hybrid learning environments, ePortfolios offer an essential structure for continuity, supporting pre-service teachers in pacing their learning, archiving critique, and tracing conceptual growth. In particular, ePortfolios provide space for iterative engagement with complex content, such as the equal sign or mathematical equivalence—a foundational mathematical concept that remains widely misunderstood by learners and under-addressed in teacher education (Alibali, Sidney & Knuth, 2017; Knuth et al., 2006).

This study focuses on how ePortfolios can support PSTs in confronting and addressing persistent misconceptions about the role of the equal sign as a relational construct. These challenges are exacerbated by gaps in conceptual understanding and limited opportunities for structured reflection on content and pedagogy (Spaull & Kotze, 2015). The ePortfolios were used as an intervention mechanism to help pre-service teachers design lessons to promote learners’ understanding of the relational concept of the equal sign or mathematical equivalence. Embedded within a CL methodology and grounded in CHAT, the intervention positioned ePortfolios as more than just a means of documenting progress. They became central mediating artefacts through which PSTs navigated post-pandemic disruptions, regulated their own learning, and reshaped their emerging professional identities. Through the integration of video-recorded lecturer critiques, PSTs were able to confront and deepen their conceptual understanding of the equal sign as a relational symbol. The iterative cycles of feedback and revision encouraged PSTs to reflect critically on their practice, revise their pedagogical choices, and, in the process, reframe their emerging professional identities in response to post-pandemic challenges and opportunities. The study, therefore, aims to address the following research questions:

- How did the ePortfolio support pre-service teachers’ reflection and adaptation in a hybrid learning environment?

- In what ways did the video-recorded lecturer’s critique influence pre-service teachers’ conceptual understanding of the equal sign?

- How did pre-service teachers use iterative feedback and revision to reframe their professional identities?

To address these research questions, the chapter is organised as follows. It begins with the theoretical framework that underpins the study, drawing on CHAT and CL methodology. This is followed by a review of relevant literature, focusing on four key areas: digital resilience and hybrid learning in teacher education; the role of ePortfolios as mediational and resilience-building tools; conceptual challenges associated with the equal sign; and the significance of reflection, feedback, and professional identity formation in pre-service teacher development. The next section outlines the methodology, detailing the research design, participants and context, data sources, and the structure of the reflective feedback cycles, alongside ethical considerations. The findings are then presented in relation to each of the three research questions. The chapter concludes by discussing the implications of the findings for theory and practice, particularly regarding the integration of ePortfolios in teacher education.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This study is grounded in Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), a socio-cultural framework that conceptualises human learning as deeply embedded in collective activity systems mediated by tools, community norms, division of labour, and evolving goals (Engeström, 1987; Vygotsky, 1978). Developed from Vygotsky’s foundational insights, CHAT posits that learning is not an individual cognitive process isolated from context, but a socially situated, tool-mediated activity where contradictions and tensions drive development. Within the context of this study, the ePortfolio served as a mediating artefact—a digital tool through which PSTs externalised their thinking, engaged with feedback, and documented their professional learning. CHAT allows us to examine how PSTs navigated the complex interplay between tools (e.g. ePortfolios, critique videos), community (lecturers and peers), rules (e.g. feedback protocols), and evolving professional identities (subjects) while working toward an educational goal (object): conceptualising and teaching the equal sign as a relational construct.

Engeström (2001; 2015) extended CHAT into a framework for understanding organisational transformation by introducing the concept of activity systems, which can expand and change through iterative resolution of internal contradictions. Central to this is the expansive learning cycle, a non-linear process in which learners move beyond rote reproduction of knowledge to reconstruct the object of their activity—often prompted by disturbances or contradictions in practice. In this case, the persistent misunderstanding of the equal sign—seen by many PSTs as merely an operational signal (Knuth et al., 2006; Alibali et al., 2017)—served as the primary epistemological contradiction. Addressing this required PSTs to reconceptualise both mathematical content and pedagogical strategies, a process enabled by iterative critique, reflection, and redesign cycles housed within their ePortfolios.

To operationalise expansive learning in practice, this study employed the CL methodology, a structured intervention approach developed by Engeström and colleagues (Engeström, 2007; Virkkunen & Newnham, 2013). Change Laboratories are formative interventions in which participants collectively analyse and transform their work practices through cycles of questioning, historical analysis, modelling new solutions, examining their feasibility, and consolidating innovations. Importantly, CL is not merely a professional development tool, but a transformative learning environment that fosters agency, reflection, and conceptual innovation (Hopwood, 2024).

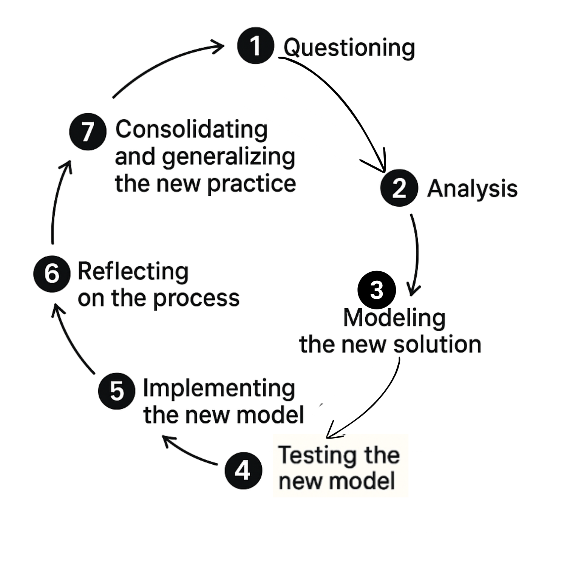

In the study, the CL was adapted into a five-phase process—initial lesson design, peer video review, lecturer video critique, lesson revision, and ePortfolio reflection—each corresponding to key stages of Engeström’s (2007) expansive learning cycle (see Figure 1). For example, the lecturers’ video-recorded critiques functioned as mirror data—a CL tool designed to provoke reflection by surfacing problematic practices or unexamined assumptions. These critiques exposed the procedural understanding many PSTs held regarding the equal sign, creating a tension between the object and current practice, and prompting deeper conceptual engagement.

Figure 1

The Expansive Learning Cycle

The ePortfolio became a dynamic platform for what Engeström (2001) calls double stimulation, where students are provided with a problematic situation (first stimulus) and a mediating tool (second stimulus) to resolve it. Here, the misunderstanding of equivalence was the first stimulus, and the ePortfolio—with its affordances for asynchronous annotation, feedback tracking, and iterative design—was the second. By documenting feedback responses, lesson revisions, and personal reflections, PSTs engaged in dialogic self-confrontation, a key mechanism of identity development in CL (Virkkunen & Newnham, 2013).

Moreover, this framework is sensitive to the digital and emotional dimensions of learning in post-COVID hybrid environments. Drawing on Bozkurt and Sharma’s (2020) concept of digital resilience, the ePortfolio scaffolded not only cognitive processing but also emotional regulation by allowing PSTs to control the pace and timing of their engagement with feedback. Recent empirical work (Babaee, Swabey & Prosser, 2021; Almendingen et al., 2021) has confirmed that when structured properly, ePortfolios enable PSTs to manage critique, trace their growth, and develop feedback literacy (Winstone & Boud, 2020)—an understanding of feedback as dialogic, actionable, and integral to identity development.

Finally, CHAT’s recognition of identity as a dynamic and evolving element within activity systems aligns with Beauchamp and Thomas’s (2009) conceptualisation of professional identity formation in teacher education. As PSTs revised their lessons, responded to critique, and curated their learning trajectories within the ePortfolio, they engaged in narrative identity construction (McAdams, 2019). This process marked a shift from passive recipients of knowledge to agentic, reflective practitioners. In sum, this study’s theoretical framework integrates CHAT, CL, and expansive learning theory to illuminate how ePortfolios operated both as tools of mediation and transformation. It reveals how PSTs, working through conceptual and pedagogical contradictions, undertook expansive learning—reshaping their understanding of mathematical equivalence and reconstituting their professional identities within a digitally mediated, post-pandemic context.

LITERATURE REVIEW

To situate this study within the broader landscape of post-COVID teacher education, the following review synthesises recent scholarship (2020–2025) across four key areas: (1) digital resilience and hybrid learning in teacher preparation, (2) the evolving role of ePortfolios as mediational tools, (3) pre-service teachers’ conceptual challenges with the equal sign in mathematics, and (4) professional identity formation through reflective practice. Each theme is grounded in relevant empirical or theoretical literature.

Digital Resilience and Hybrid Learning in Teacher Education

The sudden shift to emergency remote teaching in early 2020 highlighted significant gaps in pre-service teachers’ preparedness to navigate digital learning environments (Whalen, 2020). In response, digital resilience has emerged as a critical competency—defined as the capacity to persist, self-regulate, and adapt in the face of technological disruptions and uncertainty (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2020). Whalen (2020) observed that teacher candidates who demonstrated greater resilience were more effective at managing both cognitive load and emotional stress during online practicum. Expanding on this, Bozkurt et al. (2021) conceptualise digital resilience as encompassing both affective dimensions (e.g. coping with uncertainty) and cognitive strategies (e.g. troubleshooting and platform navigation), emphasising that such resilience is best cultivated through structured, reflective practices rather than ad hoc technical support. Giles, Baker, and Willis (2020) demonstrated that targeted interventions—such as scaffolded technology training coupled with peer mentoring—significantly improved PSTs’ self-efficacy in hybrid teaching settings.

ePortfolios as Mediational and Resilience-Building Tools

Initially designed as tools for static assessment, ePortfolios have since evolved into dynamic, interactive spaces that support ongoing professional learning—particularly when thoughtfully embedded within teacher education curricula (Modise & Mudau, 2023). Recent research underscores the role of digital tools in fostering resilience in teacher education, especially post-pandemic. E-portfolios help pre-service teachers (PSTs) articulate their teaching philosophy and meet professional standards (Babaee et al., 2021). Similarly, Lam (2024) frames e-portfolios as mediational artefacts that bridge theory and practice by externalising thinking and enabling double stimulation (Engeström, 2015). Winstone and Boud (2020) propose that ePortfolios enhance feedback literacy by making the evolution of ideas visible, thus empowering learners to track their own progress and adapt their strategies. A systematic review by Almendingen et al. (2021) confirms that ePortfolios, when coupled with structured reflection prompts and peer review mechanisms, significantly enhance PSTs’ capacity for self-regulated learning and resilience in hybrid contexts.

Conceptual Challenges with the Equal Sign

Although the equal sign is a fundamental component of mathematical understanding, it is frequently misunderstood by both learners and pre-service teachers (PSTs). Seminal research by Knuth et al. (2006) and Alibali, Sidney, and Knuth (2017) revealed that many learners interpret the symbol “=” as an operational prompt—signalling “write the answer” rather than a relational symbol of equivalence. Recent studies confirm the persistence of this misconception: Fitzmaurice et al. (2019) found that pre-service teachers could solve linear equations correctly despite lacking deep conceptual understanding, reflecting a procedural view of the equal sign.Spaull and Kotze (2015) demonstrated that if PSTs do not first reconceptualise concepts like the equal sign, they inadvertently perpetuate misunderstandings in K–12 classrooms, contributing to “silent exclusion” of struggling learners. Addressing this requires explicit conceptual interventions: Tsimane and Jina-Asvat (2026) show that when PSTs engaged with variation-based lesson activities highlighting equivalence, their ability to design conceptually robust instruction improved.

Reflection, Feedback, and Professional Identity Formation

Professional identity formation in PSTs is tightly linked to reflective practice and authentic feedback (Schön, 1983; Beauchamp & Thomas, 2009). The CL methodology, grounded in CHAT (Engeström, 2007), engages participants in cycles of critique, modelling, and redesign—catalysing expansive learning and identity transformation (Hopwood, 2024). Recent research indicates that ePortfolios create dialogic spaces that support critical reflection and transformative learning among prospective teachers, although systematic observation and follow-up dialogue are crucial for maximizing their potential (Liu, 2017). Drawing on Winstone and Boud’s (2020) concept of feedback literacy, PSTs develop an understanding of feedback as a dialogic, rather than transmissive, process—crucial for their emerging professional selves.

While the literature affirms the potential of ePortfolios to foster reflection, feedback literacy, and conceptual clarity, there remains a paucity of research explicitly linking ePortfolios to digital resilience in hybrid mathematics teacher education, particularly in interventions targeting persistent misconceptions like the equal sign. This chapter addresses this gap by examining how an ePortfolio-anchored CL intervention supports PSTs in adapting to feedback, reconstructing conceptions of the equal sign, and developing resilient, reflective professional identities in a post-COVID hybrid learning context.

METHODOLOGY

This study employed a qualitative case study design, which is well-suited for exploring complex learning processes within authentic educational contexts (Creswell & Poth, 2017). The case was bounded by a specific group of pre-service mathematics teachers participating in a structured intervention that integrated ePortfolios within a CL framework. It focused on how these participants engaged in iterative cycles of lesson design, video-based lecturer critique, and reflective practice in a hybrid learning environment. The boundaries of the case were defined by the duration of the intervention, the use of ePortfolios as the primary mediating tool, and the conceptual focus on teaching the equal sign as a relational construct.

The study unfolded over six phases, as summarised below:

- Initial Lesson Design in Change Laboratories – PSTs in triads designed and voice-recorded PowerPoint presentations of their Grade 7 introductory mathematics lessons focused on the equal sign as a relational concept. They wrote weekly reflections.

- PST triads uploaded voice-recorded PowerPoint presentations of their Grade 7 introductory mathematics lessons for peer review.

- Lecturer Video Critique – One presentation received a detailed, recorded critique from lecturers.

- Individually, PSTs reflected on the feedback from the Lecturer Video Critique and explained how they would use the feedback to improve their lessons.

- Lesson Revision – Based on all feedback, PSTs revised their lessons collaboratively.

- ePortfolio Compilation – Each PST uploaded final lessons, reflections, and feedback responses to the LMS-hosted ePortfolio.

This structure reflected the expansive learning cycle—questioning, analysis, modelling, implementation, and consolidation—adapted from Engeström (2007).

Participants and Context

The participants comprised 115 second-year pre-service mathematics teachers enrolled in a hybrid methodology course at a South African university. The course combined face-to-face tutorials and asynchronous online components, including video critique, peer feedback, and ePortfolio submissions. The cohort was predominantly female and multilingual, aligning with the broader demographic trends in South African teacher education.

Data Sources

Three primary data sources were analysed to capture PSTs’ engagement with the intervention and their evolving thinking throughout the process:

Set A: Weekly Reflections – These were collaboratively written group reflections submitted at the end of each week, documenting challenges encountered, and breakthroughs achieved during lesson planning. They provided insight into collective sense-making, emerging pedagogical reasoning, and the negotiation of conceptual understanding among peers.

Set B: Structured Responses to Critique – After viewing video-recorded lecturer critiques of their initial lesson designs, individual PSTs responded to a set of four structured questions. These responses were designed to elicit their interpretations of the feedback, clarify their understanding of the equal sign, and outline intended areas for improvement.

Set C: Lesson Revision Rationales – Following the critique sessions, individuals or groups submitted written rationales explaining the specific changes made to their lesson plans. These documents offered direct evidence of how feedback was interpreted and translated into pedagogical action, revealing the depth of reflection and conceptual shifts.

All data were collected through the university’s learning management system (LMS) over the duration of the intervention. Submissions were exported and organised within NVivo qualitative analysis software to support coding, thematic categorisation, and the identification of patterns across the data sets.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance was granted by the university’s ethics committee, and all procedures adhered to strict ethical guidelines. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the data collection and analysis process.

Data Analysis

Guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) inductive thematic coding approach and framed within CHAT and the CL methodology, we conducted a two‐cycle coding of all three data sets—A (weekly change laboratory reflections), B (written responses to four structured critique questions), and C (revision rationales for six lesson designs). Throughout, we treated the ePortfolio as the central mediational tool fostering digital resilience in post-COVID hybrid environments.

1. Data Preparation and Case Definition

Cases were defined per group per data source: each group’s Week 1–4 reflections (Set A), each individual’s four-question response (Set B), and each revised lesson rationale (Set C) constituted discrete cases in NVivo.

We imported all artefacts into NVivo and linked them to the corresponding participant ID and group.

2. First Cycle (Open) Coding

We conducted line-by-line, in vivo coding on each data set separately, generating over 600 initial codes that captured participants’ language and emergent insights.

Set A (Weekly Reflections)

Identifying Misconceptions: “Some learners may think that the equal sign always means ‘makes’…”

Conflict & Resolution: “We had many disagreements and arguments about learners’ misconceptions, but…”

Scaffolding Strategies: “We decided to deal with these misconceptions by…visual aids.”

Process Reflections: “The significance of overcoming misconceptions…ongoing assessment.”

Set B (Structured Critique Responses)

Critique Agreement: “I agree with the lecturers’ critiques because they highlight key issues…”

Influence on Planning: “The critique made me see how examples should move from simple to complex…”

Focus for Revision: “I would like to explore the lesson outcomes…they were too much for the time allocated.”

Mode Comparison: “The recorded feedback allows you quick and easy access…rewind if you did not understand.”

Set C (Revision Rationales)

Procedural→Conceptual Shift: “We changed our first example because it was…not an equation.”

Explicit Definition: “In my revision, I define ‘balanced statement’ before showing examples.”

Link to Video Critique: “I linked the video clip timestamp to the slide we revised…”

Tool Use Reflection: “Using the ePortfolio, I could track each iteration across versions.”

3. Second Cycle (Axial) Coding & Theme Development

We clustered these initial codes across all data sets into four interrelated themes, each corresponding to a CHAT component and collectively illustrating how the ePortfolio scaffolded digital resilience in a disrupted, hybrid post-COVID context:

Table 1

Four interrelated themes (created by Authors)

|

Theme |

Representative Codes |

CHAT Component |

Digital Resilience Lens |

|

1. Iterative Reflection & Revision |

“Weekly reflections helped us track progress”; “I used video feedback to pinpoint and fix specific errors”; “Each draft in the ePortfolio shows my learning arc.” |

Tools (Mediating Artefacts) |

ePortfolio enabled self-paced, asynchronous engagement across all three data sets, allowing PSTs to regulate emotional responses and pacing. |

|

2. Transformative Conceptual Shift |

“I learned the equal sign is a balance, not just an answer”; “We restructured examples to foreground equivalence”; “Defining ‘balanced statement’ before exercises.” |

Object (Learning Object) |

ePortfolio entries surfaced and corrected deep-seated misconceptions about the equal sign, a critical conceptual shift in mathematics teaching. |

|

3. Feedback as Mediational Input |

“Critique influenced my planning choices”; “Video’s rewind feature enriched my understanding”; “Linking feedback timestamps to slide revisions.” |

Rules & Division of Labour |

Multi-lecturer video critiques, stored and accessed via ePortfolio, standardised norms and roles, enabling collaborative sense-making in hybrid mode. |

|

4. Identity Formation through Narrative |

“I feel like a real teacher now”; “Documenting my story in ePortfolio made me own my professional growth”; “Seeing expert critique shifted my self-image.” |

Subject (Learner Identity) |

Curating multimedia artefacts and reflections in ePortfolio nurtured PSTs’ emerging professional identities, building confidence in digital spaces. |

|

|

|

|

|

4. Integrating Across Data Sets

Set A reflections trace the process of identifying challenges and planning strategies, illustrating early digital resilience work as PSTs negotiated hybrid collaboration norms.

Set B responses capture the immediate impact of video critique on conceptual and pedagogical stances, showing how asynchronous feedback—archived in the ePortfolio—became a go-to resource for pause-replay reflection.

Set C rationales demonstrate the sustained transformation: each lesson revision explicitly references conceptual shifts around the equal sign and ties back to critique moments, all curated in the ePortfolio.

Together, these cycles show how the ePortfolio functioned as the primary tool for joint sense-making, self-regulation, and identity work—key facets of digital resilience in an educational landscape still grappling with post-COVID disruptions.

By making the ePortfolio the dynamic hub of this intervention—storing weekly group reflections (Set A), individual critique responses (Set B), and revision rationales (Set C)—we enabled PSTs to adapt, self-pace, and proactively engage with feedback and peers. This afforded them the emotional and cognitive bandwidth to confront and correct their misunderstandings of the equal sign, ultimately fostering a conceptually robust, identity-conscious, and digitally resilient cohort of future mathematics teachers.

RESULTS AND FINDINGS

The results presented here illuminate the intricate process through which mathematics pre-service teachers (PSTs) engaged with lesson critique, conceptual reflection, and iterative revision during a CL intervention framed by CHAT. Drawing from three integrated data sets—weekly reflections (Set A), structured responses to video-recorded critiques (Set B), and revision rationales (Set C)—we show how the ePortfolio functioned as a central mediational tool that enabled digital resilience, conceptual reconfiguration, and identity formation in a hybrid post-COVID teacher education landscape.

Grounded in expansive learning theory (Engeström, 2007), the ePortfolio became not only a site of documentation but a space of transformation, enabling PSTs to negotiate contradictions, articulate learning, and embed feedback in ongoing pedagogical development.

Research Question 1: How did the ePortfolio support reflection and adaptation in a hybrid learning environment?

The ePortfolio served as a central hub for asynchronous reflection, iterative revision, and collaborative sense-making, particularly valuable in the disrupted and flexible modalities of post-COVID higher education. As the core technological artefact in the activity system, it enabled PSTs to mediate between critique and action and to curate their learning trajectories.

Many PSTs reported that the ePortfolio’s structure and digital affordances allowed them to pace their engagement with feedback and manage the emotional intensity of critique.

“Watching the video critique was better than receiving written feedback. I paused when it got too much and came back later,” wrote one PST in their structured reflection (Set B). Another noted, “I am not a very interactive person, so I can understand better when I listen to a video than when I am in a live discussion” (Set B).

The flexibility of the tool enabled PSTs to revisit critiques multiple times before committing to revisions.

“In my ePortfolio, I linked the timestamp of the lecturers’ comments directly to the slide we changed. That way, I could show the before and after,” one PST explained in their revision notes (Set C).

This traceable documentation of growth across time illustrates how the ePortfolio supported resilience—not merely in coping with critique but in harnessing it productively.

Weekly group reflections (Set A) often revealed how the digital structure of the ePortfolio sustained dialogue across group members even when synchronous engagement was difficult. One group reported,

“We reflected on what each of us understood the critique to mean and then divided the changes. The ePortfolio helped us keep track.”

Here, the ePortfolio scaffolded collaborative accountability, allowing groups to maintain cohesion despite hybrid time zones, illness, and load-shedding interruptions common in South Africa’s post-COVID educational landscape.

This aligns with Hascher and Sonntagbauer’s (2013) findings that digital portfolios can support self-regulated learning and professional growth, especially when structured around feedback loops and self-evaluation. As such, the ePortfolio served not only as a mirror for reflection but also as a technological anchor amidst pedagogical uncertainty.

Research Question 2: In what ways did the video-recorded lecturer critique influence PSTs’ conceptual understanding of the equal sign?

Across all data sets, participants revealed a major conceptual shift in their understanding of the equal sign—from a procedural cue (e.g. “write the answer here”) to a relational symbol of mathematical equivalence. This shift was consistently attributed to the lecturers’ multi-voiced, recorded critique, which PSTs could rewatch, annotate, and embed in their revision narratives. This mediational process speaks directly to the CL model of expansive learning, where contradictions become generative (Engeström et al., 2014).

One PST described their early misconception:

“I always saw the equal sign as the place where you put the answer. I never thought about it, meaning both sides are the same.”

Another shared how the critique made them re-evaluate their example:

“I used to say 3 + 4 = and then leave it open. But after watching the video, I realised that wasn’t teaching balance—it was just prompting an answer.”

The shift was also evident in design revisions, with one PST noting:

“I added a number sentence like 4 + 3 = 2 + 5 to show learners the equal sign doesn’t always mean ‘give the answer.’”

In early reflections (Set A), many PSTs struggled to articulate what it meant for two expressions to be equivalent.

For instance, one group wrote in Week 1: “Some learners may think the equal sign always means ‘makes’ or ‘the answer is’. We are not sure how to show otherwise.”

After watching the critique video, PSTs began re-evaluating their lesson design decisions with greater precision. One PST (Set B) wrote, “I learned that the equal sign is not just a signal for the answer; it’s a symbol that shows a relationship. That changes how I explain it to learners.” Others focused on specific examples flagged in the critique: “We had used 3 + 4 = 7 as an example, but now I see we need to also show 7 = 3 + 4 and 3 + 4 = 2 + 5 to show equality” (Set C).

The feedback prompted not just minor adjustments but a fundamental restructuring of the learning sequence. One revision note explained, “We inserted a new slide before any definitions. It uses concrete examples to show balanced and unbalanced scales. Only after that do we talk about the equal sign.” This intentional scaffolding shows a direct application of variation theory principles (Marton, 2006), adapted to support conceptual insight rather than rote correctness.

Multiple PSTs commented on how video critique helped them overcome personal blind spots. As one PST noted, “When the lecturer said we ourselves were unclear about the equal sign, I was shocked. But watching again, I saw what she meant.”

Research Question 3: In what ways did the video-recorded lecturer critique influence PSTs’ conceptual understanding of the equal sign?

Across all data sets, participants revealed a major conceptual shift in their understanding of the equal sign—from a procedural cue (e.g. “write the answer here”) to a relational symbol of mathematical equivalence. This shift was consistently attributed to the lecturers’ multi-voiced, recorded critique, which PSTs could rewatch, annotate, and embed in their revision narratives. This mediational process speaks directly to the CL model of expansive learning, where contradictions become generative (Engeström et al., 2014).

One PST described their early misconception:

“I always saw the equal sign as the place where you put the answer. I never thought about it, meaning both sides are the same.”

Another shared how the critique made them re-evaluate their example:

“I used to say 3 + 4 = and then leave it open. But after watching the video, I realised that wasn’t teaching balance—it was just prompting an answer.”

The shift was also evident in design revisions, with one PST noting:

“I added a number sentence like 4 + 3 = 2 + 5 to show learners the equal sign doesn’t always mean ‘give the answer.’”

In early reflections (Set A), many PSTs struggled to articulate what it meant for two expressions to be equivalent.

For instance, one group wrote in Week 1: “Some learners may think the equal sign always means ‘makes’ or ‘the answer is’. We are not sure how to show otherwise.”

After watching the critique video, PSTs began re-evaluating their lesson design decisions with greater precision. One PST (Set B) wrote, “I learned that the equal sign is not just a signal for the answer; it’s a symbol that shows a relationship. That changes how I explain it to learners.” Others focused on specific examples flagged in the critique: “We had used 3 + 4 = 7 as an example, but now I see we need to also show 7 = 3 + 4 and 3 + 4 = 2 + 5 to show equality” (Set C).

The feedback prompted not just minor adjustments but a fundamental restructuring of the learning sequence. One revision note explained, “We inserted a new slide before any definitions. It uses concrete examples to show balanced and unbalanced scales. Only after that do we talk about the equal sign.” This intentional scaffolding shows a direct application of variation theory principles (Marton, 2006), adapted to support conceptual insight rather than rote correctness.

Multiple PSTs commented on how video critique helped them overcome personal blind spots. As one PST noted, “When the lecturer said we ourselves were unclear about the equal sign, I was shocked. But watching again, I saw what she meant.”

The video-recorded lecturer critique served as a catalyst for PSTs’ shift from viewing the equal sign as a procedural cue to recognising it as a relational symbol of equivalence. This transformation resonates with Alibali et al.’s (2017) critique that school mathematics often privileges operational over relational meanings and reflects Engeström’s (2001) notion of mirror data, where critical perspectives expose contradictions that prompt new understandings. By being revisitable through the ePortfolio, the critique became a sustained mediational tool, enabling PSTs to pause, rewatch, and annotate feedback as they restructured lesson designs. Their revisions—from using balanced and unbalanced scales to sequencing examples of non-standard equations—illustrate how conceptual clarity translated into pedagogical change, consistent with variation theory (Marton, 2006). Thus, the recorded critique acted simultaneously as a mirror for misconceptions and a scaffold for transformation, fostering deeper professional learning through iterative reflection and design.

Research Question 4: How did PSTs use iterative feedback and revision to reframe their professional identities?

As PSTs engaged repeatedly with critique, revised their lessons, and narrated their thought processes in the ePortfolio, they began to articulate a more confident, agentic professional identity. Rather than seeing feedback as correction, they began seeing themselves as teachers responsible for clarity, coherence, and conceptual integrity in learners’ experiences.

One PST wrote, “Before, I just followed the CAPS document. Now I think about what learners might misunderstand and how to prevent that. That makes me feel more like a real teacher.” This comment reflects a growing ownership over the lesson as a designed learning experience rather than a set of instructions.

Others pointed to the ePortfolio as a reflective canvas where identity work could unfold: “I looked back at my first draft and my final version and realised how much I’ve grown. The ePortfolio shows my thinking, not just the slides.” This supports research by McAdams (2019), who highlights that the narrative of the ePortfolio has the power to capture both product and process in teacher formation.

The collaborative and multi-lecturer nature of the critique further broadened PSTs’ perspectives. As one group reflected, “There were things that one lecturer didn’t mention, but another did. Together, they made us rethink our assumptions.” Rather than defensive responses, these reflections reveal a developing professional humility, a willingness to learn from multiple sources.

Another PST noted, “At first, I was annoyed that our lesson got so much critique. But watching the video again, I saw that they were trying to help us reach higher standards.” This internalisation of critique as professional discourse rather than personal attack is a crucial shift in identity, particularly for new teachers navigating high-stakes assessment cultures.

Finally, some PSTs described how the portfolio fostered long-term investment in their own growth: “I can use this portfolio to prepare for my next teaching prac. It reminds me what to focus on.” Thus, identity work was not episodic but extended and cumulative, layered into the ePortfolio through narrative, evidence, and critique response.

This study makes several novel contributions. First, it demonstrates how ePortfolios—when scaffolded through a CL process—can support PSTs in developing timestamp-linked justification practices that go beyond surface reflection. Second, the use of video critique not only surfaced misconceptions (e.g. regarding the equal sign) but also fostered metacognitive agency as PSTs revisited their lessons through new eyes. Finally, the emotional labour embedded in receiving peer feedback was productively mediated by group reflection, showing that affective resilience can be cultivated in hybrid teacher education settings through collaborative design environments.

Together, the data show that this CL intervention, supported by a well-structured ePortfolio, catalysed expansive learning cycles across cognitive, emotional, and professional dimensions. The video critique acted as a powerful mediational tool, surfacing deep-seated misconceptions about the equal sign, while the ePortfolio became a flexible, resilient site for negotiating those tensions into pedagogical insight.

In a hybrid, post-pandemic environment, where instructional time is fragmented and feedback channels are stretched, this model demonstrates that ePortfolios can anchor professional growth, make learning visible, and sustain conceptual development when conditions are unstable. In doing so, they support digital resilience, not as a passive coping strategy but as a proactive mode of reflection, revision, and identity-building.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

This study set out to examine how ePortfolios, situated within a CL framework, supported PSTs as they adapted, reflected, and reimagined themselves professionally in a hybrid teacher education environment. Our discussion is organised around the three research questions, each aligned with central themes of the volume—resilience, identity, and reflection—to foreground how the post-pandemic context shaped learning processes.

Supporting Reflection and Adaptation Through the ePortfolio (RQ1)

In the wake of COVID-19 disruptions, teacher education programs were compelled to find new ways of engaging PSTs in deep reflection and professional development across digital and hybrid platforms (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2020; Whalen, 2020). The ePortfolio in this study acted as both a mediational and motivational artefact offering a structure to support adaptive resilience—the ability to learn, reflect, and adjust within unstable conditions (Zhang & Tur, 2025; Lam, 2024).

By enabling PSTs to document and revise lesson designs, respond to feedback, and justify pedagogical decisions, the ePortfolio promoted reflection through ongoing self-assessment (Kihwele, Mwamakula & Mtandi, 2024). For example, several PSTs shared that “seeing how others structured their equal sign examples helped me see gaps in my own.” This illustrates how shared artefacts encouraged metacognitive engagement. In hybrid conditions marked by discontinuity and isolation, the ePortfolio became a stable tool for tracking development and promoting agency (Ciolacu, Rachbauer & Hansen, 2022; Modise & Mudau, 2023).

Influence of Video Critique on Understanding the Equal Sign (RQ2)

A critical finding was the role of video-recorded lecturer critique in shifting PSTs’ conceptual understanding of the equal sign. Previously seen as an operational cue, the equal sign was increasingly understood as representing relational equivalence (Alibali et al., 2017; Knuth et al., 2006). These conceptual shifts were facilitated by opportunities for PSTs to revisit their own teaching, analyse feedback in relation to mathematical meaning-making, and engage in reflective dialogue that explicitly contrasted operational and relational interpretations.

The ability to pause, rewind, and reflect on critique asynchronously provided PSTs with a resilient mode of learning (Miller, Nelson & Phillips, 2021). One PST reflected:

“I always saw the equal sign as the place where you put the answer. I never thought about it, meaning both sides are the same.”

Another noted:

“I added a number sentence like 4 + 3 = 2 + 5 to show learners the equal sign doesn’t always mean ‘give the answer.’”

This aligns with Jina Asvat’s (2022) findings that scaffolded critique through visual and dialogic tools enhances learners’ conceptual understanding, a principle equally applicable to PSTs. Moreover, the opportunity to revisit critique in their own time allowed for emotional regulation and increased confidence—key indicators of digital resilience (Bozkurt et al., 2021).

Feedback, Revision, and Identity Construction (RQ3)

The iterative revision cycles embedded in the ePortfolio were more than opportunities for improvement—they were identity-forming practices. Requiring PSTs to explain why they made changes demanded engagement with both the content and their beliefs about teaching. As Beauchamp and Thomas (2009) note, professional identity is formed through critical reflection on practice, particularly when learners are encouraged to articulate their evolving role in relation to others.

For instance, one PST wrote:

“This time, I didn’t just fix the activity—I explained why it was wrong and how it might confuse learners.”

Another said:

“At first, I felt nervous about being ‘wrong,’ but now I feel like I’m building lessons as a teacher, not just a student.”

This transformation reflects expansive learning (Engeström, 2007, 2015), in which participants encounter contradictions and use them to construct new models of activity. The structured revision process enabled PSTs to transition from peripheral participation toward more central, agentic roles (Virkkunen & Newnham, 2013), fostering a sense of ownership over their teaching identities. The act of writing rationale in the ePortfolio functioned as a mediational artefact for identity work, reinforcing the importance of reflective practice in resilience development (Winstone & Boud, 2020; Schön, 1983).

Several PSTs also used the ePortfolio to process affective dimensions of the learning process, naming fear, uncertainty, and pride. This unexpected use of the portfolio as a space for emotional expression highlights its dual role as a cognitive and emotional scaffold—an insight supported by recent research on feedback and resilience in hybrid environments (Almendingen et al., 2021; Hopwood, 2024).

CONCLUSION

This chapter examined how an ePortfolio-based CL intervention supported the professional development of PSTs within a hybrid, post-pandemic learning environment. Guided by three research questions, the study illuminated the ways in which structured ePortfolio engagement, iterative revision, and mediated critique contributed to PSTs’ reflective practices, conceptual growth, and evolving professional identities.

First, the ePortfolio served as a structured and dialogic space that supported sustained reflection and adaptation. By documenting their evolving thinking, comparing peer perspectives, and justifying pedagogical choices, PSTs engaged in metacognitive processes that strengthened their ability to navigate the complexities of hybrid teaching. This reflective routine cultivated academic resilience and fostered adaptive instructional strategies.

Second, video-recorded lecturer critiques played a significant role in reshaping PSTs’ conceptual understanding of the equal sign. Through the asynchronous, visual format of the feedback, PSTs engaged deeply with moments of critique, identified misconceptions, and implemented revisions with conceptual clarity. This re-engagement with foundational mathematical concepts supported deeper learning and demonstrated the pedagogical power of critique embedded in reflective processes.

Third, iterative feedback and revision prompted PSTs to reframe their professional identities. The act of justifying lesson changes, interpreting critique, and reflecting on growth allowed PSTs to see themselves as emerging professionals. Through this process, they developed agency, resilience, and a stronger sense of purpose. The ePortfolio became more than a repository—it became a site of transformation, where PSTs authored their evolving roles in teaching and learning.

Collectively, these findings suggest that an intentionally designed ePortfolio intervention—anchored in a strong theoretical framework and enriched by structured critique and reflection—can foster meaningful shifts in both conceptual understanding and professional identity. In post-COVID teacher education contexts, where flexibility, emotional regulation, and self-directed learning are increasingly critical, such interventions offer powerful models for developing reflective, resilient, and conceptually grounded educators.

REFERENCES

Alibali, M. W., Sidney, P. G., & Knuth, E. J. (2017). The equal sign. In S. R. Goldman & C. E. Snow (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology: Vol. 2. Cognition (pp. 531–546). Oxford University Press.

Almendingen, M., Wathne, M., & Grepperud, S. (2021). ePortfolio implementation for professional learning and resilience in hybrid teacher education. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 37(2), 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2020.1846962

Babaee, M., Swabey, K., & Prosser, M. (2021). The role of E-portfolios in higher education: The experience of pre-service teachers. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 37(4), 247-261.

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252

Bozkurt, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to Coronavirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), i–vi. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3778083

Bozkurt, A., Koul, R., & Dagistan, E. (2021). Measuring digital resilience in teacher preparation: A mixed-methods study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103340.

Ciolacu, M. I., Rachbauer, T., & Hansen, C. (2022, September). Education 4.0 in the new normal–higher education goes agile with E-Portfolio. In International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (pp. 289-299). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Creswell J. W., Poth C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Engeström, Y. (2007). Putting activity theory to work: The Change Laboratory as an application of double stimulation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky (pp. 363–382). Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Fitzmaurice, O., O’Meara, N., Johnson, P., & Lacey, S. (2019). ‘Crossing’ the equal’s sign: insights into pre-service teachers’ understanding of linear equations. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(4), 361-382.

Foreman-Brown, G., Fitzpatrick, E., & Twyford, K. (2023). Reimagining teacher identity in the post-Covid-19 university: becoming digitally savvy, reflective in practice, collaborative, and relational. Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 40(1), 18-26.

Giles, M., Baker, S. F., & Willis, J. M. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ peer mentoring experience and its influence on technology proficiency. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 28(5), 602-624.

Hopwood, N. (2024). Twenty-five years of change laboratories in schools: a critical and formative review. Educational Action Research, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2024.2379343

Jina Asvat, Z. (2022). Semantic waves and their affordances for teaching scaffolding to pre-service teachers. Reading & Writing – Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa, 13(1), 346.

Kihwele, J. E., Mwamakula, E. N., & Mtandi, R. (2024). Portfolio-based assessment feedback and development of pedagogical skills among instructors and pre-service teachers. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education.

Knuth, E. J., Stephens, A. C., McNeil, N. M., & Alibali, M. W. (2006). Does understanding the equal sign matter? Evidence from relational and arithmetic strategies. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 37(5), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/30034902

Lam, R. (2024). Understanding the usefulness of e-portfolios: Linking artefacts, reflection, and validation. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 62(2), 405-428.

Liu, K. (2017). Creating a dialogic space for prospective teacher critical reflection and transformative learning. Reflective Practice, 18(6), 805-820.

McAdams, D. P. (2019). “First we invented stories, then they changed us”: The evolution of narrative identity. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 3(1), 1-18.

Miller, L. R., Nelson, F. P., & Phillips, E. L. (2021). Exploring critical reflection in a virtual learning community in teacher education. Reflective Practice, 22(3), 362-380.

Modise, M. E. P., & Mudau, P. K. (2023). Using E-Portfolios for Meaningful Teaching and Learning in Distance Education in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 71(3), 286-298.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Spaull, N., & Kotze, J. (2015). Starting behind and staying behind in South Africa: The case of insurmountable learning deficits in mathematics. International Journal of Educational Development, 41, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.01.002

Tsimane, T., & Jina-Asvat, Z. (2026, January). Beyond PCK: Rethinking knowledge development in pre-service teachers through K-STEP. Paper to be presented at the Southern African Association for Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education (SAARMSTE 2026), University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Virkkunen, J., & Newnham, D. S. (2013). The Change Laboratory: A tool for collaborative development of work and education. Sense Publishers.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Whalen, J. (2020). Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 189-199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00558-y

Winstone, N., & Boud, D. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A review of feedback literacy. Routledge.

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2025). Enacting learning agency through ePortfolio implementation: An exploratory study. International Journal, 15(1), 13-31.

AUTHORS

Dr. Zaheera Jina–Asvat is a Lecturer in Mathematics Education at the Wits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. She obtained her PhD in Education, specialising in Mathematics Education, from Wits University. Her research focuses on the intersections between teacher identity, pedagogical content knowledge, and classroom practice, with particular interest in how pre-service and in-service teachers’ fluid identities influence their conceptual engagement and reflective practice. She also examines how course design can support identity development and professional growth in mathematics education. Zaheera serves as the Head of the B.Ed Programme and the Chair of the Library Committee.

Email: zaheera.jina@wits.ac.za

Dr. Lawan Abdulhamid is an NRF Rated Researcher and Senior Lecturer at the Wits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. He obtained his PhD in Mathematics Education from Wits in 2016. His research primarily focuses on supporting the development of mathematics teaching at the primary school level, with a particular interest in the use of video-stimulated recall as a reflective tool for professional learning. He also explores the use of technology in teaching and assessment as a secondary research interest. Lawan serves as Chair of the WSoE Ethics Committee and was Head of the B.Ed Honours programme from 2020 to 2024.

Email: Lawan.Abdulhamid@wits.ac.za