18 Digital ePortfolios for Aspiring Educators: Fostering Reflective Practice and Creativity in PhD Students

Irene (JC) Lubbe, University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Yurgos Politis, Abu Dhabi University, United Arab Emirates

ABSTRACT

This chapter presents a design-based case study detailing the implementation of digital ePortfolios to foster reflective practice and creativity among doctoral students aspiring to academic teaching roles. In response to the growing need for pedagogical competence among PhD candidates, particularly those navigating diverse educational systems with limited teaching experience, the authors outline a pedagogical intervention within a Certificate of Teaching in Higher Education programme. The initiative involved replacing a traditional paper-based module with a dynamic digital ePortfolio module developed on the WIX™ platform. This transition allowed students to progressively curate and align artifacts that illustrate their teaching development, pedagogical philosophies, and emerging professional identities. In doing so, the module explicitly cultivates digital resilience, such as the ability to adapt pedagogical practice to evolving technologies while maintaining accessibility, ethical data practices, and audience-aware multimodal design. The ePortfolio model integrates private reflections and public-facing narratives, encouraging multimodal expression and iterative revision through scaffolded activities, explicit instruction, and collaborative learning. The chapter draws on multiple theoretical frameworks, including Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory, Schön’s reflective practitioner model, the TPACK framework, and the ASMAR evaluative rubric, to support a pedagogical design grounded in metacognition, digital fluency, and creative identity formation. Outcomes of this approach included improved alignment of teaching artifacts, enhanced depth of reflection, and increased student confidence in presenting their academic identities to professional audiences. While challenges such as digital fluency and institutional support were acknowledged, the approach highlights the potential of thoughtfully designed digital ePortfolios to bridge the gap between doctoral training and the academic job market. The chapter contributes to broader discussions on innovative assessment, digital resilience, and identity-centred pedagogy in doctoral education.

Keywords: ePortfolios, Doctoral Student Development, Capstone Project Pedagogy, Digital Transformation of Learning, Digitalisation, Reflective Practice in Teaching

INTRODUCTION

In today’s increasingly competitive academic job market, doctoral students are expected not only to demonstrate research excellence but also to articulate a coherent and compelling teaching identity (Cassuto, 2022; Oliveira, Nada, & Magalhães, 2025; Irish Universities Association [IUA], 2021). For international PhD candidates in particular, showcasing pedagogical competence and reflective practice presents distinct challenges due to diverse educational backgrounds and often limited access to formal teaching experiences. In response to these challenges, digital teaching portfolios have emerged as valuable tools, enabling aspiring educators to curate, reflect upon, and creatively present their teaching development in ways that are both authentic and professionally relevant (Chye, 2021).

This chapter outlines the rationale and pedagogical design underpinning a digital ePortfolio approach developed within a Certificate of Teaching in Higher Education programme at a university in Central Europe. Specifically, it describes how a capstone module titled “Starting your teaching portfolio” was restructured to replace a static, paper-based assignment with a dynamic, multimodal ePortfolio (“Creating a Digital Teaching Portfolio”) hosted on the WIX™ platform. Designed to be completed over a six-week period, the module builds directly on artifacts created in earlier certificate modules, such as draft teaching philosophies, initial syllabi, and collaboratively developed lesson plans. These existing materials serve as a scaffold: students revisit each artifact, extend it with multimedia and narrative elements, and integrate it into a coherent portfolio structure that reflects both their pedagogical development and creative expression.

Scaffolding was achieved through sequenced workshops, milestone deadlines, and feedback loops that progressively deepened both technical and reflective skills. For example, an early milestone required embedding a revised teaching philosophy into the portfolio framework; a mid-point checkpoint focused on integrating at least two multimedia artifacts with accompanying reflective commentary; and the final submission involved a peer-reviewed synthesis of all components into a cohesive professional narrative.

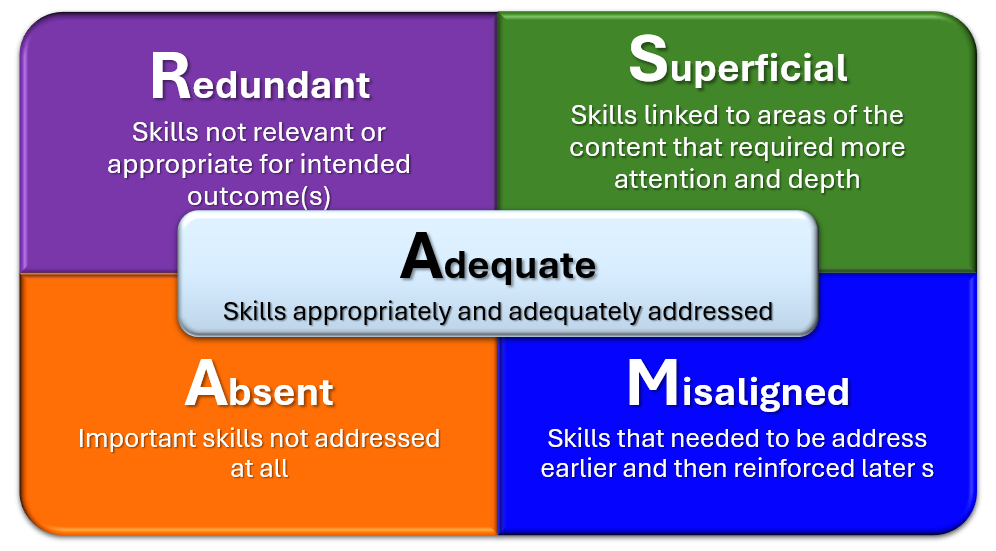

The decision to shift from a paper-based to a digital format was part of a broader curriculum renewal process. To guide this redesign, the authors employed the ASMAR framework (Lubbe & Politis, 2025), a diagnostic tool developed to assess the content and structure of academic modules during re-curriculation. ASMAR evaluates whether content is Adequate, Superficial, Misaligned in terms of placement, Absent or Missing, or Redundant. Applying this framework to the previous iteration of the portfolio module revealed areas of superficial engagement with teaching philosophy, misaligned sequencing of artifact development, and absent opportunities for iterative reflection and multimodal composition. These findings prompted the development of a redesigned module that emphasized longitudinal learning, scaffolded portfolio construction, and digital storytelling.

The ePortfolio design centres on three pedagogical imperatives: fostering reflective practice, enhancing creative expression, and supporting the formation of academic teaching identities. Reflective writing and portfolio development are well-established strategies for promoting metacognition and self-regulated learning (Yang, Wang, & Lim, 2023), and digital platforms enhance these processes by allowing for audience-aware communication, iterative feedback, and multimodal storytelling (Barrett, 2010).

Drawing on theoretical frameworks such as Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT), Schön’s reflective practitioner model, and the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, the course is intentionally structured to support identity work, scaffolded reflection, and digital fluency. The integration of these frameworks reflects a broader commitment to preparing doctoral students for the communicative, pedagogical, and technological demands of contemporary higher education.

Rather than providing a summative evaluation of implementation outcomes, this chapter focuses on the pedagogical rationale for the redesign, the structure of the digital ePortfolio module, and the strategies used to support students’ reflective and creative engagement. In doing so, it contributes to the ongoing discourse on doctoral education reform, innovative assessment practices, and the role of digital ePortfolios in bridging the gap between scholarly preparation and professional practice.

METHODOLOGY

Context and Participants

This chapter reports a design-based case study situated in a capstone module within a Certificate of Teaching in Higher Education at a university in Central Europe. The module replaced a paper-based portfolio with a digital ePortfolio built on the WIX™ platform and was completed over six weeks. Participants were doctoral students enrolled in the program and engaged in scaffolded portfolio construction aligned to earlier coursework artifacts (e.g., teaching philosophies, syllabi, lesson plans).

Engagement With Participants (Students)

Participants met in one facilitated session per week over the six-week module. Sessions were designed to be interactive rather than lecture based. Each meeting opened with a brief demonstration or mini workshop focused on the week’s portfolio task, followed by structured, hands-on building time in which participants worked on their ePortfolios with real-time instructor support.

Peer learning was built into every session. Participants periodically shared works-in-progress, used prompt-based discussion to articulate design decisions, and engaged in guided peer feedback on content, structure, accessibility, and reflective depth. Instructor circulation and brief one-to-one consultations supported troubleshooting and helped students connect portfolio choices to prior coursework (e.g., teaching philosophy, syllabus, and lesson planning).

Between sessions, participants continued developing their ePortfolios asynchronously. We provided concise written prompts and milestone checklists to scaffold reflection and artefact selection; formative comments were returned within the subsequent session to sustain momentum. This combination of weekly synchronous interaction and supported independent work was intended to cultivate technical fluency with the platform and progressively more sophisticated reflective writing while preserving participants’ control over audience settings and individual pages’ public/private status.

Data Sources and Analysis

Because the primary aim was pedagogical design and implementation rather than formal hypothesis testing, evidence reported here derives from routine educational sources: formative feedback cycles, facilitator observations during the six-week sequence, and students’ own reflective writing within the portfolios. Analysis was interpretive and practice-oriented: the authors reviewed reflections, feedback, and artefacts to identify recurring patterns (e.g., increased alignment between artefacts and stated philosophies; deeper metacognitive articulation) and used these insights to refine prompts, scaffolds, and support iteratively. Thus, this work is presented as a design-based account of curriculum improvement, not a summative empirical evaluation.

Ethical Considerations

All materials referenced were generated as part of credit-bearing coursework. No demographic or sensitive personal data is reported. Student quotations, where used, are anonymized; no identifying details are included. The chosen platform permits private and public-facing pages, and students retained control over audience settings for their portfolios. The chapter focuses on curriculum design and pedagogical practice; accordingly, claims are descriptive and illustrative rather than generalizable.

THEORETICAL AND PEDAGOGICAL FOUNDATIONS

Across the global higher education landscape, increasing emphasis is being placed on preparing future academics not only as researchers but as capable educators. To this end, universities are expanding faculty development offerings through both formal (e.g., certificates, diplomas, master’s degrees) and informal (e.g., workshops, micro-credentials) pathways (Lubbe & Politis, 2025). Despite these developments, many higher education institutions (HEIs) continue to neglect structured pedagogical training for doctoral candidates, even as national-level policies recognize its necessity (IUA, 2021; Rifkin et al., 2023). In response to this gap, the authors co-developed a redesigned Certificate of Teaching in Higher Education tailored specifically for PhD students, with core modules in pedagogy and didactics, classroom observation, and a capstone module focused on the creation of a digital teaching portfolio (Politis & Lubbe, 2025).

The teaching portfolio serves as more than a repository of documents. It functions as a curated narrative of an educator’s development, typically including a teaching philosophy, instructional artifacts, reflections, and evidence of pedagogical competence (Ashwin et al., 2015; Davis & Fitzpatrick, 2019; Sebolao, 2019). As a reflective artifact, it allows individuals to critically engage with their teaching identity, values, and professional growth.

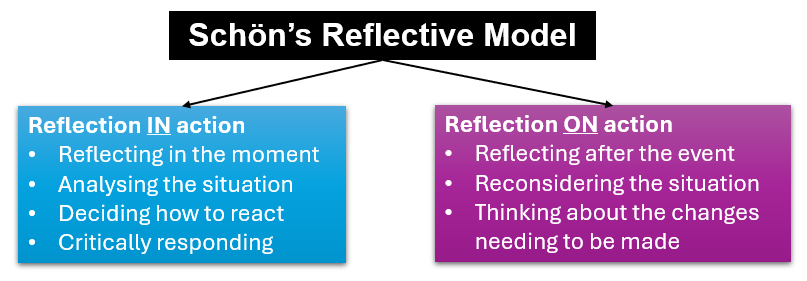

Central to the portfolio’s conceptual foundation is Donald Schön’s (1983) notion of the “reflective practitioner,” which frames teaching as a process of inquiry grounded in reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. By challenging the dominance of technical rationality in professional education, Schön emphasized the role of educators as self-directed learners navigating complex, uncertain environments. This model informs the reflective structure of the ePortfolio, which prompts doctoral students to examine not only what they teach, but also why and how they teach.

Figure 1

Schön‘s Reflective Model

Building on Schön’s work, contemporary scholarship advocates for a deeper, critical reflection that interrogates identity, power, and positionality within teaching practice (Chye, 2021). For international PhD students, this form of reflection is especially important as they navigate differing institutional cultures and pedagogical expectations. Digital ePortfolios, when designed with this complexity in mind, can function as spaces for both critical engagement and professional articulation.

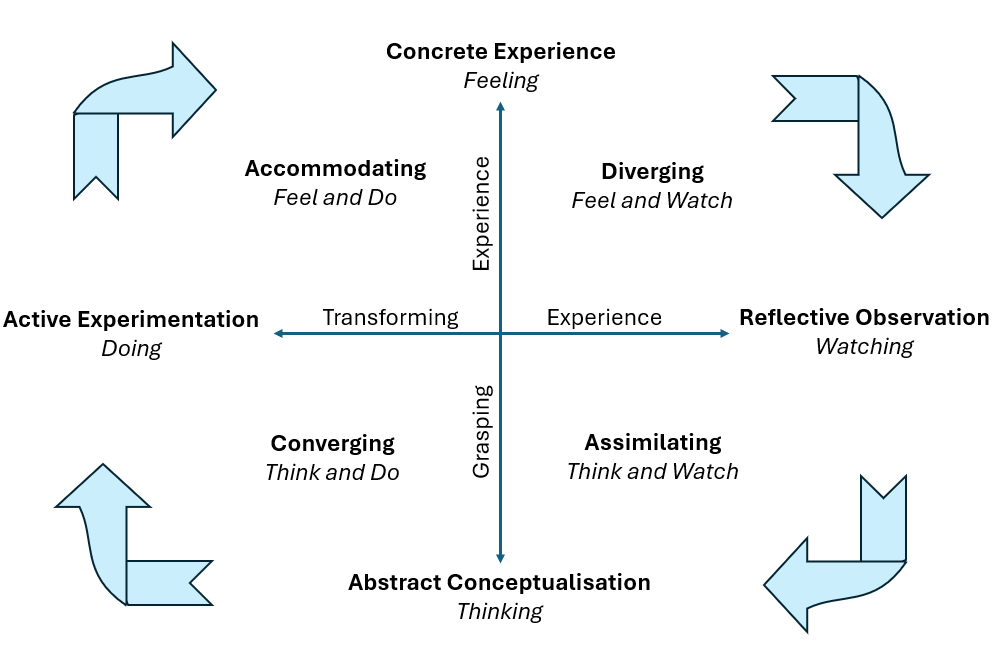

To further support reflective learning, the course design draws on Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Theory (ELT), which describes learning as a cyclical process of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. This model aligns with the iterative nature of portfolio development, wherein students generate, analyze, revise, and reapply pedagogical insights across different teaching contexts.

Figure 2

Kolb‘s Learning Styles

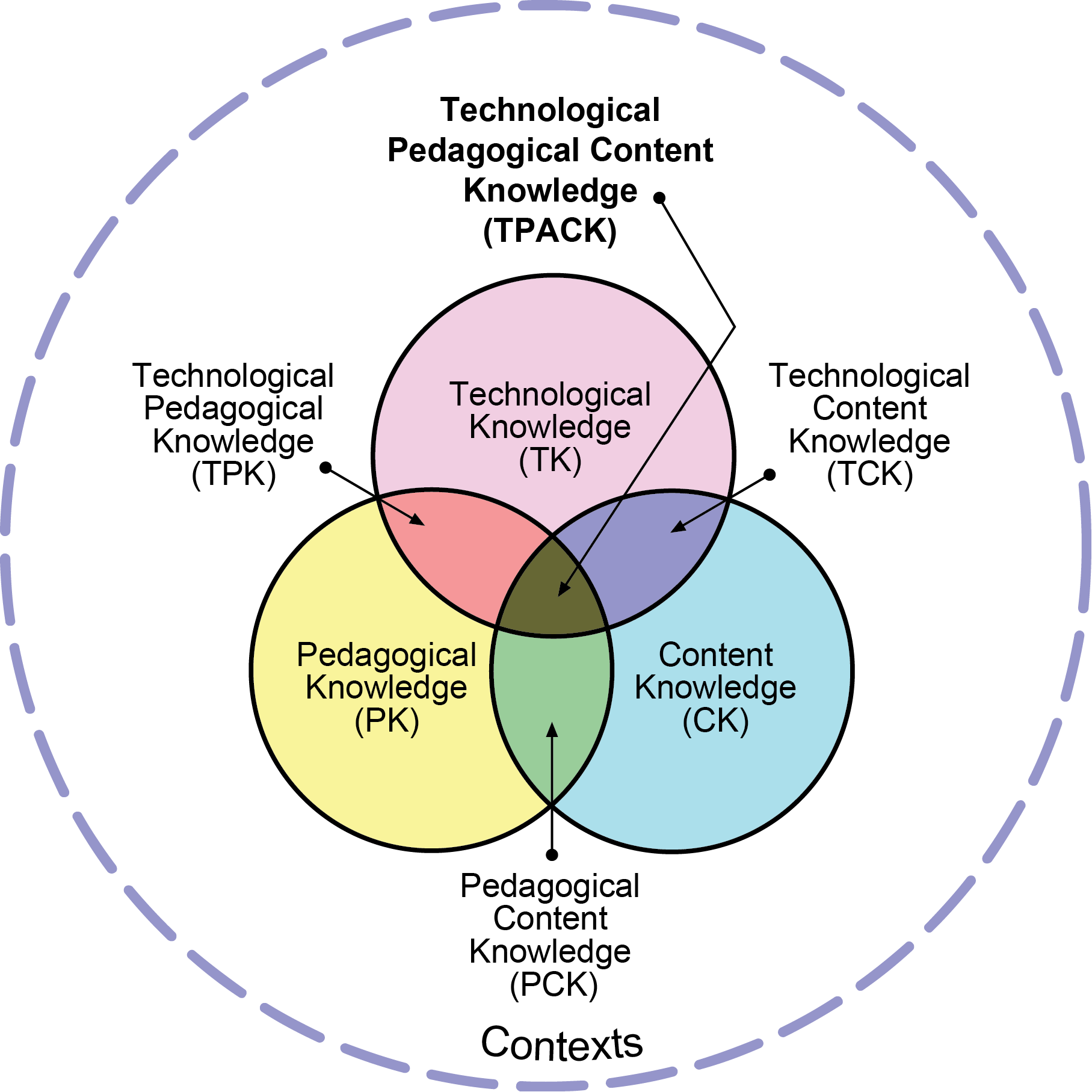

Complementing these reflection-based models is the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, which articulates the intersection of three essential domains: content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and technological knowledge (Mishra & Koehler, 2006). As students construct digital ePortfolios, they are required to engage simultaneously with all three, producing teaching artifacts that are pedagogically sound, technologically fluent, and content appropriate. This process fosters the development of digitally resilient educators equipped for contemporary academic environments.

Figure 3

TPACK framework

Another design framework guiding the course redesign (distinct from the portfolio assessment itself) was the ASMAR framework (Lubbe & Politis, 2025). ASMAR is an acronym for five diagnostic categories used in curriculum review: Adequate, Superficial, Misaligned, Absent or Missing, and Redundant. In simple terms, it helps curriculum designers identify what is working well, what is underdeveloped, what is out of sequence, what is missing entirely, and what is unnecessarily duplicated.

We first applied ASMAR to the original paper-based version of the teaching portfolio module as part of a broader curriculum renewal. This initial scan highlighted both strengths to retain and gaps to address in the redesign, as detailed in the examples that follow.

Figure 4

ASMAR-framework

This framework enables a structured analysis of a module’s content and learning design across five diagnostic categories: Adequate, Superficial, Misaligned (in terms of content sequencing), Absent or Missing, and Redundant. In applying the ASMAR framework to the original paper-based version of the teaching portfolio module, the authors identified several design limitations, including superficial engagement with teaching philosophy, misalignment in the sequencing of artifacts, and missing opportunities for iterative development. These findings directly informed the pedagogical shift to a digital portfolio model that emphasizes longitudinal learning, scaffolded reflection, and multimodal expression.

Applying ASMAR to the earlier paper-based portfolio revealed category-specific design issues that guided the redesign:

Table 1

Application of the ASMAR Framework to the Original Paper-Based Portfolio Module (created by Authors)

|

ASMAR Category

|

Example from Old Paper-Based Module

|

Impact on Learning

|

|

Adequate |

Inclusion of a draft teaching philosophy aligned with assessment criteria. |

Provided a starting point for reflection but lacked depth and iterative development. |

|

Superficial |

Students listed teaching methods without linking them to theory or context. |

Limited critical reflection; portfolio read as a checklist rather than a narrative. |

|

Misaligned |

Introduction of lesson plan and syllabus tasks in the final two weeks. |

Prevented iterative refinement and meaningful integration into the philosophy. |

|

Absent/Missing |

No requirement for multimodal artifacts or explicit audience awareness. |

Omitted opportunities to develop digital fluency and public-facing professional identity. |

|

Redundant |

Duplication of content between syllabus and lesson plan sections. |

Reduced focus on synthesis and originality; contributed to student disengagement. |

|

|

|

|

These diagnostic findings informed the pivot toward a scaffolded, multimodal, and iterative digital ePortfolio model, ensuring that each category of the ASMAR framework was addressed in the redesign.

Together, these frameworks provide a robust theoretical and pedagogical foundation for the digital ePortfolio module. They support a curriculum that is not only academically rigorous but also responsive to the diverse developmental needs of doctoral students preparing for teaching roles in higher education.

Digital Resilience as an Intended Learning Outcome

Digital resilience, as used in this chapter, refers to the capacity to sustain effective, ethical, and inclusive teaching practice amid continuous technological change. Within the module, resilience is developed through repeated cycles of tool selection, multimodal authoring, accessibility checks, and revision, making technological agility a deliberate outcome rather than an incidental by-product of ePortfolio work (Mishra & Koehler, 2006; Walland & Shaw, 2022; Bećirović, 2023).

Link to teaching philosophy: Students iteratively articulate a digitally situated teaching philosophy that names values such as openness, inclusivity, academic integrity, and data ethics, and then demonstrates how these values inform platform choice, media selection, and accessibility decisions (e.g., structure, alt text, captioning). This positions the philosophy as a living document that can be updated as tools and institutional contexts change (Lam, 2023; Pegrum & Oakley, 2017).

Link to teaching practice: Through artifact design and re-design, students operationalize their philosophy: they prototype lessons with different media, implement universal design decisions, and use feedback/analytics to refine clarity and engagement while attending to privacy and consent. This practice-proximal iteration builds habits of adaptive decision-making that transfer beyond a single platform (Mishra & Koehler, 2006; Walland & Shaw, 2022).

Link to academic training: Framing the ePortfolio as a professional dossier normalizes evidence-informed reflection on digital choices (why this tool, for whom, with what trade-offs?), a competency increasingly expected in academic hiring and teaching-development pathways. In this sense, the module treats digital resilience as a core graduate attribute for future academics, aligning reflective identity work with pedagogical and technological judgement (Pegrum & Oakley, 2017; Bećirović, 2023).

FROM PAPER TO PLATFORM: RATIONALE FOR DIGITAL EPORTFOLIOS

The previous iteration of the capstone module within the Certificate of Teaching in Higher Education programme required students to submit a paper-based teaching portfolio. Typically, this included a draft teaching philosophy, a rudimentary syllabus, and a collaboratively developed lesson plan. While this structure offered a starting point for reflective engagement, it lacked the flexibility, interactivity, and authenticity needed to fully capture doctoral students’ pedagogical development.

Paper-based portfolios inherently constrain expression. They tend to promote static documentation over dynamic learning, limit opportunities for iterative feedback, and restrict the use of multimodal or audience-aware communication. As Walland and Shaw (2022) observe, such formats often fail to engage students in the reflective and creative processes essential for developing professional identities in digital academic contexts.

Recognizing these limitations, the authors undertook a comprehensive redesign of the module, guided by the ASMAR framework (Lubbe & Politis, 2025). This diagnostic tool enabled a systematic analysis of the module’s content and structure, revealing multiple deficiencies: the teaching philosophy component was treated superficially; key artifacts were introduced too late in the process to allow meaningful development; and opportunities for reflection were inconsistently scaffolded. Additionally, the absence of digital literacy integration was notable, especially given the increasing relevance of such competencies in higher education. The resulting shift to a digital ePortfolio model was not a simple platform upgrade, but a pedagogical transformation. By leveraging the capabilities of the WIX™ platform, the redesigned module supports multimodal storytelling, iterative revision, and a more authentic representation of teaching identity. Students are empowered to present their pedagogical narratives through multimedia artifacts, including narrated presentations, video reflections, and interactive content, that extend beyond what is possible in print-based formats.

Importantly, the WIX™ platform allows for both private and public-facing content, enabling students to strategically control how they present their professional identities to different audiences. This dual functionality aligns with the module’s aim to balance introspective reflection with outward-facing professional articulation. Moreover, the use of digital ePortfolios facilitates constructive alignment between teaching, learning, and assessment. Students curate and narrate artifacts that demonstrate their pedagogical growth across dimensions such as instructional design, inclusivity, and assessment practice. These components are not merely collected but contextualized through reflective commentary, reinforcing the idea of the portfolio as a living document that evolves in response to feedback, practice, and self-inquiry.

The move to a digital format also fosters the development of transversal skills such as digital communication, visual design, and audience awareness, that are increasingly valued in academic and professional contexts (Bećirović, 2023). By engaging with the technological affordances of WIX™, students refine their ability to communicate complex ideas clearly, creatively, and professionally. Ultimately, the transition from paper to platform represents a deliberate alignment of pedagogical purpose with digital possibility. It supports not only the documentation of teaching development, but also the formation of adaptable, digitally literate, and reflective educators prepared to meet the evolving demands of academic work.

Critical Perspectives and Limitations

While the shift to digital ePortfolios offers clear pedagogical advantages, critiques in the literature caution against assuming that technology alone guarantees deeper learning. For instance, Walland and Shaw (2022) note tensions between institutional expectations for innovation and the realities of student capacity, particularly where digital skills are unevenly distributed. Barrett (2010) warns that without robust scaffolding and feedback, portfolios can devolve into static “digital filing cabinets,” offering little more than their paper predecessors. Others point to issues of sustainability and platform dependency; portfolios built on commercial tools may be subject to changes in pricing, functionality, or data policies that compromise long-term accessibility (Bećirović, 2023). Finally, while ePortfolios can foster creativity, some critics question whether they impose additional cognitive load, diverting attention from the substance of teaching philosophy and practice to design aesthetics. Recognising these critiques emphasize the importance of intentionality – pairing digital platforms with intentional pedagogy, institutional support, and a focus on reflective depth over visual polish.

Distinctive Features of the (free) WIX™-Based Model

While ePortfolios have been implemented in a range of platforms (including institutionally hosted learning management systems and Mahara), the WIX™-based model described here offers distinctive advantages in the context of doctoral teaching development. Unlike template-driven platforms, WIX™ allows for high levels of design flexibility without requiring advanced coding skills, enabling students to experiment with layout, navigation, and multimodal integration in ways that mirror authentic professional web presence. This flexibility supports narrative coherence across diverse artifact types, from interactive lesson plans to embedded video micro-lectures, while retaining control over privacy settings for audience-specific sharing. In contrast, platforms such as Mahara, while powerful, can present steeper learning curves and may require additional institutional hosting or technical support. Moreover, integrating the platform into a scaffolded curriculum, rather than as a stand-alone digital task, ensured that design decisions were always anchored in pedagogical intent. Looking ahead, this model is adaptable to incorporate emerging features such as AI-assisted content analysis and feedback, offering new possibilities for targeted reflection and skill development.

DESIGNING THE EPORTFOLIO EXPERIENCE

The “Creating a Digital Teaching Portfolio” module was intentionally structured to guide doctoral students through a scaffolded, reflective, and creative process of constructing a professional ePortfolio. Grounded in best practices in ePortfolio pedagogy and aligned with the broader learning outcomes of the Certificate in Teaching in Higher Education, the module integrates scaffolding, collaborative learning, explicit instruction, digital fluency development, and metacognitive strategies, each aimed at fostering academic identity formation, critical reflection, and professional presentation.

Scaffolded and Iterative Portfolio Development

Scaffolding was a central design principle. Students constructed their portfolios incrementally across six weeks, beginning with foundational artifacts developed earlier in the programme, including a teaching philosophy, sample syllabi, lesson plans, as well as teaching and assessment artifacts. These were then expanded to include additional artifacts, narrations, reflections, and integrative commentaries. This phased approach ensured that learning was cumulative, not compressed, and encouraged sustained engagement.

Example Milestones and Deadlines in Practice

To provide a replicable structure for beginner practitioners, the six-week module incorporated explicit milestone dates and deliverables:

- Week 1: Create WIX™-shell and populate it with bio-statement and CV. Upload initial teaching philosophy drafted in earlier certificate modules; annotate with one area identified for further development.

- Week 2: Integrate one pre-existing artifact (e.g., syllabus) into the digital platform; add a short description or reflective paragraph linking it to stated teaching values.

- Week 3: Add at least one new multimedia artifact (e.g., narrated presentation, microteaching video, teaching artifact) accompanied by reflective commentary.

- Week 4: Peer-review exchange. Students review two peers’ portfolios focusing on logical flow, narrative coherence, artifact alignment, and accessibility.

- Week 5: Implement feedback from peers and facilitators; revise two or more artifacts for clarity, design, and accessibility.

- Week 6: Final submission and showcasing of the integrated portfolio.

Each milestone was linked to formative feedback from instructors and peers, ensuring students could iteratively refine both technical execution and reflective depth. This clear, time-bound structure also supported workload management and sustained engagement across the cohort.

This design reflects evidence that structured, iterative development fosters deeper reflection and more coherent professional narratives (Pegrum & Oakley, 2017). Clear milestones, scaffolded deadlines, and formative feedback loops enabled students to progressively align their artifacts with their evolving pedagogical values. As Ellis (2017) emphasizes, such iterative approaches enhance both the quality of student reflection and the intentionality of portfolio composition.

Digital Fluency and Technical Support

Recognizing variability in students’ digital competencies, the module incorporated early and ongoing orientation to the WIX™ platform. This included self-paced tutorials and in-class demonstrations to support diverse learning preferences and levels of confidence. Rather than assuming digital literacy, the course explicitly addressed it as a learning objective, reinforcing Walland and Shaw’s (2022) argument that digital fluency must be scaffolded, especially in international or interdisciplinary cohorts.

The technical instruction was not merely instrumental but also pedagogical, helping students understand how digital tools could enhance narrative coherence, audience engagement, and multimodal expression. Visual design, platform navigability, and content accessibility were treated as integral components of effective teaching representation. Framing these technical choices as reflective trade-offs (e.g., aesthetics vs. accessibility; interactivity vs. cognitive load; convenience vs. data privacy) made digital fluency consequential and helped students cultivate digital resilience as a repeatable judgement process rather than a one-off skill (Mishra & Koehler, 2006; Walland & Shaw, 2022).

Collaborative Learning and Peer Feedback

Collaboration was woven into the module through structured peer review and asynchronous feedback exchanges. Students shared drafts of key components, such as teaching philosophies, narrated artifacts, and layout choices, and received feedback from both peers and facilitators. These interactions promoted dialogic learning and exposed students to diverse pedagogical strategies and storytelling methods. Consistent with Walland and Shaw’s (2022) findings, peer engagement enhanced the depth of student reflection and fostered transversal competencies such as empathy, critical listening, and constructive communication.

Chang and Kabilan (2022) highlight the value of peer dialogue in deepening reflective practice and refining academic voice. Within the module, peer engagement served not only to enhance artifact quality but also to build a supportive learning community, mitigating the isolation often experienced in doctoral programmes.

Explicit Instruction, Modelling, and Exemplars

Given the dual conceptual and technical demands of digital portfolio creation, explicit instruction was essential. Facilitators modelled effective practices using platform-specific examples and faculty portfolios. These exemplars illustrated narrative coherence, multimodal integration, and design aesthetics, clarifying expectations and supporting cognitive transfer (Lam, 2023).

Instructors also demonstrated how to translate reflective insights into compelling teaching narratives, thereby helping students bridge the gap between personal experience and professional articulation. Modelling provided students with concrete referents for quality, tone, and structure, reducing ambiguity and building confidence.

Metacognitive Strategies and Reflective Prompts

Metacognitive engagement was embedded throughout the module via reflective prompts and self-assessment checklists. Students were asked to interrogate not only what they had done, but also why they made specific pedagogical choices and how their perspectives were evolving. Prompts such as “What did this experience reveal about your teaching values?” and “How might this artifact communicate your approach to inclusivity?” supported higher-order reflection.

This design draws on Deweyan principles of experiential learning (Simpson & Jackson, 1997; Malik & Behera, 2024) and aligns with Ellis’ (2017) findings that structured reflection fosters professional growth. Encouraging students to link experience with theory, intention, and identity helped transform the portfolio from a compliance task into a meaningful tool for academic development.

Formative Feedback and Revision Culture

Facilitators provided ongoing, individualized feedback focused on both content and design. This included commentary on the clarity of teaching philosophies, alignment of artifacts with learning outcomes, narrative coherence, and technical execution. Students were encouraged to revise and redesign components, reinforcing the portfolio’s function as a living document and promoting a culture of continuous improvement.

This feedback-rich model mirrors best practices in ePortfolio pedagogy, emphasizing revision as central to learning (Walland & Shaw, 2022). The iterative process not only strengthened the final outputs but also cultivated a reflective, agile mindset essential for navigating complex teaching environments.

Together, these pedagogical and facilitative strategies strengthen the portfolio’s role as a reflective space and a professional showcase. The module empowered doctoral students to articulate their evolving teaching identities with clarity, creativity, and confidence – positioning them as digitally fluent, pedagogically reflective, and professionally prepared educators.

OUTCOMES AND IMPACT

The shift to digital ePortfolios yielded notable enhancements in the quality of student outputs, depth of reflection, and creative expression. While this chapter does not report formal research findings, several pedagogically significant outcomes emerged through formal end-of-module feedback cycles, student reflections, and facilitator observations. Students demonstrated deeper levels of critical reflection compared to previous cohorts engaged in paper-based portfolios. This shift was most evident in their ability to articulate evolving teaching philosophies, interrogate pedagogical decisions, and draw connections between instructional theory and personal experience. The integration of reflective prompts and scaffolded revision cycles supported this growth by encouraging metacognitive engagement and continuous self-assessment.

These findings align with Pegrum and Oakley (2017), who report that digital ePortfolios enable richer, more sustained reflection by providing flexible spaces for narrative, revision, and multimedia integration. The opportunity to express ideas through visual, auditory, and textual modes also contributed to more nuanced and authentic articulations of professional identity (Ellis, 2017).

The quality and coherence of teaching artifacts improved substantially under the digital format. Students demonstrated greater intentionality in aligning artifacts (such as lesson plans, syllabi, and narrated videos) with their stated teaching philosophies and broader pedagogical commitments. This alignment was facilitated by structured peer and instructor feedback, which helped students revise artifacts for both clarity and relevance.

In contrast to the fragmented submissions typical of earlier iterations of the module, digital ePortfolios encouraged students to develop integrated teaching narratives. Each artifact was framed within a cohesive story about their development as educators, enabling assessors to trace learning trajectories across the portfolio.

Beyond academic development, digital ePortfolios positioned students to engage more effectively with the academic job market. By curating a public-facing narrative of their pedagogical expertise and values, students developed professional assets that could be shared with hiring committees, teaching centres, and peer networks.

Overall, student reception of the digital ePortfolio experience was positive. Many expressed appreciations for the opportunity to experiment with voice, tone, and design, and valued the platform’s capacity to represent their teaching competencies in dynamic and visually engaging ways. Students noted that the process of crafting their ePortfolio encouraged them to reflect more deeply on their goals as future academics and to think strategically about how to present themselves to prospective employers. While specific student quotations have been anonymized for confidentiality, feedback consistently highlighted the perceived professional utility of the portfolio. One student described the value as “… in the beginning I could not see the value of the portfolio, but I have applied for a TA position two weeks ago and used my portfolio as part of my application – and I got the job! “

As Pegrum and Oakley (2017) argue, a well-constructed ePortfolio serves not only as an assessment tool but also as a professional dossier, demonstrating a candidate’s ability to integrate theory, practice, and reflection into a coherent teaching identity. In this way, digital ePortfolios contributed to students’ professional readiness by enhancing their ability to communicate their academic narratives in multimodal, audience-aware formats.

While the observations and examples presented here provide insight into the pedagogical impact of the redesigned module, they are based primarily on formative feedback, facilitator reflections, and anonymised student self-reports. These sources offer valuable practitioner perspectives but do not constitute formal empirical evaluation. Future research could strengthen the evidence base by incorporating pre- and post-intervention measures of reflective depth, digital fluency, and teaching identity, alongside independent evaluations of portfolio quality. Such data would enable a more systematic assessment of the model’s effectiveness across different cohorts and institutional contexts.

CHALLENGES AND LESSONS LEARNED

While the implementation of digital ePortfolios demonstrated clear pedagogical value, it was not without significant challenges. These emerged across three main areas: variability in student engagement and digital fluency, resource constraints, and the need for institutional and stakeholder alignment.

Variability in Digital Fluency and Engagement

A recurring challenge was the uneven digital literacy among students. While some embraced the creative possibilities of WIX™ with confidence, others struggled with the technical aspects of designing and maintaining a digital portfolio. These disparities were not simply matters of platform familiarity; they reflected broader differences in access, prior exposure to digital tools, and self-efficacy in navigating new technologies.

To mitigate these gaps, the course included asynchronous tutorial resources and optional drop-in support. Despite these supports, some students required ongoing guidance throughout the module, suggesting the need for even earlier integration of digital skill-building into the broader certificate curriculum. As Walland and Shaw (2022) emphasize, embedding digital competencies as a developmental trajectory, not a one-off workshop, is essential for equitable engagement.

Variability was also evident in levels of student investment. While most engaged thoughtfully with the portfolio process, a minority approached it as a compliance task. This underlines the importance of framing the portfolio not merely as an assessment artifact but as a transformative tool for professional identity formation.

Time, Workload, and Resource Constraints

The iterative nature of portfolio development requires a substantial time investment, both from students, who must reflect and revise, and from instructors, who provide feedback, model exemplars, and facilitate technical troubleshooting. These demands can strain programme capacity, particularly in resource-constrained contexts or programmes serving large cohorts.

Strategies adopted to address this included staggered deadlines, streamlined rubrics, and collaborative peer-review processes that distributed some of the evaluative labour. Nonetheless, the workload implications of maintaining high-quality formative feedback remain significant and merit continued attention in future iterations.

Additionally, reliable access to technology (both software and hardware) cannot be assumed, particularly for international students or those working in low-resource environments. Institutions implementing ePortfolios must ensure that adequate infrastructure and support systems are in place to avoid deepening digital inequities.

Stakeholder Buy-In and Institutional Support

Sustainable integration of digital ePortfolios into doctoral education requires broad stakeholder engagement. Faculty, administrators, IT staff, and teaching and learning centres all play roles in ensuring that portfolios are valued, resourced, and aligned with institutional goals.

Engaging these stakeholders early in the redesign process was critical to securing buy-in and ensuring the module’s viability. Institutional recognition of the portfolio’s value as both a pedagogical and professional development tool, enhanced its legitimacy and helped to secure ongoing support. As Pegrum and Oakley (2017) and Lam (2023) note, embedding ePortfolios into the institutional fabric requires more than technical training; it requires a cultural shift that embraces digital storytelling as a legitimate mode of scholarly expression.

Design Responsiveness and Agile Iteration

A key lesson from the implementation process was the importance of agility. The course adopted a design-based approach, with ongoing refinements made in response to student feedback, facilitator insights, and emerging challenges. Scaffolded deadlines, targeted support sessions, and iterative prompt revision were all part of a responsive pedagogy that valued continuous improvement.

This agile stance reflects Brookfield’s (2017) call for critically reflective teaching that adapts to context, listens to learners, and evolves over time. This responsiveness mirrors the course’s own iterative design ethos, integrating reflection and re-design as central to professional education.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The redesign and implementation of digital ePortfolios within doctoral teaching development offer several critical insights for educators, curriculum designers, and institutions aiming to enhance reflective practice, digital fluency, and academic identity formation. These implications are grouped into three domains: pedagogical recommendations, cross-contextual transferability, and broader contributions to digital resilience and lifelong learning.

Recommendations for Educators and Programme Designers

To support the effective adoption of digital ePortfolios, educators and programme developers should consider the following pedagogical recommendations:

Clarify expectations through exemplars and modelling. Provide a range of portfolio examples from previous cohorts or faculty to illustrate structure, tone, and multimodal integration. This scaffolds student understanding and reduces ambiguity (Lam, 2023).

Integrate iterative feedback within a clearly sequenced activity structure. Designing for progressive complexity enables deeper engagement and supports longitudinal reflection (Pegrum & Oakley, 2017).

Embed digital literacy support. Ensure early and ongoing access to tutorials, technical guides, and support sessions. Integrating digital fluency into broader curriculum design can help reduce disparities in student readiness (Walland & Shaw, 2022).

Foster a collaborative learning culture. Encourage peer review, shared dialogue, and collective inquiry as part of the portfolio process. These practices enhance reflection and foster a sense of professional community (Ellis, 2017; Chang & Kabilan, 2022).

Transferability to Other Disciplines and Contexts

While this case study is situated within a doctoral-level teaching programme, the pedagogical principles underpinning the digital ePortfolio model are transferable across disciplines. In STEM, humanities, social sciences, and professional fields, portfolios can be adapted to showcase discipline-specific skills, learning trajectories, and reflective competencies.

Programme designers seeking to adapt this model should ensure that portfolio criteria are contextually grounded and aligned with disciplinary expectations, professional standards, and the intended audience. The flexibility of digital platforms makes them particularly suitable for tailoring across varied academic cultures.

Fostering Digital Resilience and Lifelong Learning

Beyond immediate course-based goals, digital ePortfolios contribute to a broader agenda of cultivating digitally resilient and reflective professionals. By engaging with digital tools in meaningful ways, students develop competencies in digital storytelling, self-presentation, critical reflection, and adaptive learning.

These are essential capacities in an academic landscape increasingly shaped by hybrid modalities, digital scholarship, and evolving expectations for teaching and learning. As Walland and Shaw (2022) argue, ePortfolios can serve as catalysts for lifelong learning, equipping students to continually assess, represent, and renew their professional identities.

In practical terms, we recommend making digital resilience assessable by asking students to justify platform and media choices, annotate artifacts with accessibility and privacy decisions, and document at least one redesign based on analytics or peer feedback. These moves align reflective stance with demonstrable practice, enabling novice academics to evidence readiness for technology-rich teaching contexts. Programme leaders can reinforce this by mapping ePortfolio checkpoints to institutional teaching-development frameworks and by recognising resilience-related competencies in hiring or fellowship dossiers (Pegrum & Oakley, 2017; Lam, 2023).

CONCLUSION

This chapter has examined the pedagogical rationale, design strategy, and implementation approach behind integrating digital ePortfolios into a doctoral teaching development programme. Rooted in the redesign of a capstone module within a Certificate of Teaching in Higher Education, the initiative addressed the need to equip aspiring educators with the reflective, creative, and digital competencies essential for navigating contemporary academic careers.

The shift from paper-based portfolios to digital ePortfolios was informed by the ASMAR framework and supported by a combination of experiential, reflective, and technological-pedagogical models, notably Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory, Schön’s reflective practitioner model, and the TPACK framework. These frameworks provided a conceptual basis for scaffolded learning, multimodal expression, and identity-centred reflection. Through structured peer review, iterative feedback, and technical support, students were guided in curating authentic narratives of their teaching development.

Key outcomes included enhanced reflective depth, improved alignment of pedagogical artifacts, and increased digital fluency. While challenges related to digital access, student variability, and institutional workload were encountered, they were mitigated through agile design practices and sustained facilitator engagement. The module also prompted broader conversations about stakeholder alignment and the institutional conditions required to support innovation in doctoral education.

Looking forward, digital ePortfolios offer promising avenues for integrating assessment, professional development, and identity formation in doctoral programmes. As higher education continues to evolve in response to technological change and pedagogical reform, the ability to communicate one’s academic practice – visually, narratively, and reflectively – will remain a key marker of professional readiness. Future innovations may include the integration of AI-supported feedback systems, cross-platform portfolios, and collaborative portfolio ecosystems that reflect the increasingly networked nature of academic work.

Ultimately, digital ePortfolios represent more than a change in medium; they signal a shift in pedagogy toward greater intentionality, creativity, and reflexivity in how future academics are prepared to teach, reflect, and grow.

REFERENCES

Ashwin, P., Boud, D., Calkins, S., Coate, K., Hallett, F., Light, G., Luckett, K., McArthur, J., MacLaren, I., McLean, M., & McCune, V. (2015). Reflective teaching in higher education. Bloomsbury Academic.

Barrett, H. C. (2010). Balancing the two faces of e-portfolios. Educause Quarterly, 33(4), 1–7.

Bećirović, S. (2023). Challenges and barriers for effective integration of technologies into teaching and learning. In Digital Pedagogy: The Use of Digital Technologies in Contemporary Education (pp. 123–133). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0444-0_10

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. John Wiley & Sons. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2132030275?sourcetype=Books

BusinessBalls. (2025). Kolb’s Learning Styles. https://www.businessballs.com/self-awareness/kolbs-learning-styles/

Cassuto, L. (2022) Why teaching still gets no respect in doctoral training. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 10 March 2022. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-teaching-still-gets-no-respect-in-doctoral-training. (Accessed 29 October 2024).

Chang, S. L., & Kabilan, M. K. (2022). Using social media as e-Portfolios to support learning in higher education: a literature analysis. Journal of computing in higher education, 1–28. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-022-09344-z

Chye, S. Y. L. (2021). Towards a framework for integrating digital portfolios into teacher education. TechTrends, 65, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00646-0

Davis, C.L., & Fitzpatrick, M. (2019) SEDA Special 42: Reflective Practice, London: SEDA. [online], available: https://seda.ac.uk/product/reflective-practice/

Ellis, C. (2017). The Importance of E-Portfolios for Effective Student-Facing Learning Analytics. In T. Chaudhuri & B. Cabau (Eds.), E-Portfolios in Higher Education (pp. 35–49). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3803-7_3

IUA (Irish Universities Association). (2021) Irish Universities doctoral skills statement. 3rd ed. Dublin: IUA.

Kolb, A.Y., & Kolb, D.A. (2011). The Kolb Learning Style Inventory. Experience Based Learning Systems, Inc. https://learningfromexperience.com/downloads/research-library/the-kolb-learning-style-inventory-4-0.pdf

Kolb, D.A, (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Lam, R. (2023). E-Portfolios: What We Know, What We Don’t, and What We Need to Know. RELC Journal, 54(1), 208-215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220974102

Lubbe, J.C., & Politis, Y. (2025). Strategic curriculum redesign: A triad approach with action mapping, design thinking, and change management. jeXed1(1). 33 pages. https://journals.uj.ac.za/index.php/jexed/article/download/3666/2246/13389

Malik, P., & Behera, S. (2024). The Transformative Power of Experiential Learning: Bridging Theory and Practice. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 12(2), 055-063. DIP:18.01.007.20241202, DOI:10.25215/1202.007

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Oliveira, T., Nada, C., & Magalhães, A. (2025) ‘Navigating an academic career in marketized universities: Mapping the international literature,’ Review of Educational Research, 95(2), pp.255-292. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543231226336

Pegrum, M., & Oakley, G. (2017). The Changing Landscape of E-Portfolios: Reflections on 5 Years of Implementing E-Portfolios in Pre-Service Teacher Education. In T. Chaudhuri & B. Cabau (Eds.), E-Portfolios in Higher Education (pp. 21–34). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3803-7_2

Rifkin, B., Natow, R.S., Salter, N.P., & Shorter, S. (2023) Why doctoral programs should require courses on pedagogy: The case for paying far more attention to developing teaching skills in graduate school. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 16 March 2023. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-doctoral-programs-should-require-courses-on-pedagogy?sra=true. (Accessed 29 October 2024).

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. https://raggeduniversity.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/1_x_Donald-A.-Schon-The-Reflective-Practitioner_-How-Professionals-Think-In-Action-Basic-Books-1984_redactedaa_compressed3.pdf

Sebolao, R. (2019). Enhancing the use of a teaching portfolio in higher education as a critically reflexive practice. The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(2), 20-28. [online], available: https://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2519-56702019000200003

Simpson, D.J. , & Jackson, M.J.B. (1997). Educational Reform: A Deweyan Perspective (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203825617

TPACK. (2012). Using the TPACK image. Date retrieved: Oct 24, 2025 https://tpack.org/tpack-image/

Walland, E., & Shaw, S. (2022). E-portfolios in teaching, learning and assessment: Tensions in theory and praxis. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2022.2074087

Yang, M., Wang, T., & Lim, C. P. (2023). E-portfolios as digital assessment tools in higher education. In J. M. Spector (Ed.), Learning, design, and technology (pp. 2213–2235). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17461-7_83

AUTHORS

Dr. Irene (JC) Lubbe is an experienced higher education leader and academic developer with more than two decades of international teaching, curriculum, and assessment expertise. She is currently a Curriculum and Learning Developer at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, and previously served as Director of Assessment in the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences at the University of Auckland. Irene has also held senior academic roles in South Africa and at the Central European University in Vienna, where she contributed to faculty development and doctoral teaching. Her scholarship and practice focus on curriculum transformation, innovative assessment, and playful pedagogies, with particular interest in game-based learning, digital education, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL). She has published widely on creative approaches to teaching and assessment, including the use of design thinking, co-teaching models, and gamification to foster learner engagement. Drawing on her cross-cultural experiences in Africa, Europe, and New Zealand, Irene is deeply committed to developing inclusive, future-focused educational practices that enhance student success and institutional impact. She is also a sought-after workshop facilitator, supporting colleagues in reimagining their teaching through evidence-based, learner-centred design.

Email: irene.lubbe@auckland.ac.nz

Dr. Yurgos Politis is currently an Assistant Professor at Abu Dhabi University and a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. He has a PhD in Physics Education, an MA in Education, and a BSc in Physics, which included Initial Teacher Education in year 4. His research interests since then have been diversified and cover areas such as inclusive education, adult education, lifelong learning, and higher education. Yurgos has been involved in international, interdisciplinary, and collaborative research projects, including EUROAC, UNIBILITY, COMMIT, ERSALE, and Inclusive Learning. More recently, he held a Marie Curie Fellowship, which entailed a two-year visiting scholar period at Michigan State University. That project explored the use of virtual reality for conversation skills training, initially with young autistic adults. He is currently the convenor of the World Education Research Association’s International Research network entitled “Bridging the Teaching Gap: Mapping and Enhancing Professional Development for Faculty and Early Career Researchers (TEACH-MAP).” The IRN will review the literature, conduct a survey of faculty and early-career researchers on teaching CPD, co-create CPDs with the same cohorts, & offer the training at selected events.

Email: yurgos.politis@gmail.com