12 Investigating the Paradigm Shift of Replacing Traditional School Report Cards with Developmental, Learner-Centred ePortfolios in South African Primary Schools

Amber Clarke

Two Oceans Graduate Institution, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This chapter explores the limitations of traditional South African primary school report cards, which reduce academic performance to static grades without accounting for learners’ lived contexts. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which left many learners with unresolved trauma and widened educational inequalities, there is a growing need for more inclusive reporting methods. Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, which underscores the influence of contextual factors on development, this study critiques the current reporting system and proposes a developmental learner ePortfolio as an alternative. The ePortfolio, a digital collection of learner artefacts and reflections, allows for the integration of academic, emotional, and environmental factors while maintaining data privacy. An exploratory case study was conducted through structured interviews with selected professionals, using purposive sampling aligned to Bronfenbrenner’s systems. Eighteen factors emerged as essential to designing a holistic learner ePortfolio. The chapter concludes that post-pandemic academic potential should not be judged solely by grades but by a comprehensive view of the learner’s journey, as captured through a contextualised learner ePortfolio.

Keywords: Academic Performance; Bronfenbrenner Ecological Systems Theory; COVID-19 Pandemic; Learner ePortfolio; Scholastic Report Card

INTRODUCTION

Grades recorded on a school report card carry significant weight, having short- and long-term consequences for learners (Butler, 2025; Costa et al., 2024; Paramole & Adeoye, 2024). Considered a “determinant of future success,” the report card serves as the primary verdict during the admissions process for schools, universities, and future employers (Schneider & Hutt, 2014, p. 201). It highlights each learner’s academic performance and capabilities; their performance is then judged according to their school report card (Costa et al., 2024). Research has advocated that this reporting method of using grades as a representation of learner achievement is an outdated, poor, and ineffective approach (Anderson, 2018; Butler, 2025; Kingsbury et al., 2025; Neuhaus & Jacobsen, 2022; Paramole & Adeoye, 2024).

With the closing of schools and an increase in dropout rates, there was a significant drop in school results during the COVID-19 era (Statistics South Africa, 2020). The school report card reflected this prolific drop in grades. However, it failed to capture the learners’ lived experiences, including the social, emotional, and environmental factors that shaped their academic performance during this disruptive period.

This chapter addresses the limitations of the traditional school report card with its inability to holistically capture learner development and its failure to provide educators and parents with true insights into a learner’s academic journey. Moreover, this chapter aims to uniquely identify specific contextual design characteristics for a developmental ePortfolio, grounded in Bronfenbrenner’s theory. The research contributes to the advancement of educational reporting models and fosters a more inclusive and developmentally supportive approach through the exploration of learner ePortfolios (electronic portfolios).

Learner ePortfolios, which are seen as an emerging technology, have slowly been recognised as useful electronic tools to reflect on learning progress (Yang & Wong, 2024; Hsieh et al., 2024). The description of an ePortfolio has varied across researchers and tends to differ depending on the need, topic, and purpose of the investigation (Callens & Elen, 2007). For this chapter, the following definition of a learner ePortfolio by Pallitt et al. (2015) is adopted. Pallitt et al. (2015, p. 2) classify a learner ePortfolio as a “purposeful collection of information and digital artefacts that demonstrates development or evidences learning outcomes, skills, or competencies.” These digital artefacts include digital resources (personal artefacts and facilitators’ comments), demonstration of growth and development, flexible expression (customised folders and sections that meet the skill requirements of particular tasks and areas of development), and input by multiple role players (Kok & Blignaut, 2009, p. 2).

APPROACH

To decide what should be included to create a holistic ePortfolio, a thorough literature review was conducted, and an exploratory case study consisting of structured interviews with education professionals was employed. Purposive non-probability sampling was used to select the participants within the microsystem of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, being the educator, educational psychologist, inclusive educational specialist, occupational therapist, and a parent (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Furthermore, an ePortfolio was motivated as an appropriate technological tool due to its digital benefits, such as the enforcement of cybersecurity protocols to ensure confidentiality and data protection (Hsieh et al., 2024; Yang & Wong, 2024). Ultimately, a learner ePortfolio adopts a developmental approach, redefining how academic progress is recorded, reported, and interpreted.

With the predominant argument being for a shift from the traditional school report card to a holistic, learner-centred ePortfolio, this chapter is guided by the following research questions:

- In what ways does the current school report card represent learners’ development when examined through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977)?

- Which contextual factors across these ecological systems constitute essential design characteristics that should be embedded in a learner’s ePortfolio to align with a holistic, ecological view of learner development (Bronfenbrenner, 1977)?

- How can a learner’s ePortfolio, structured by Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977), generate a holistic representation of that learner’s achievement?

LITERATURE REVIEW

This section examines relevant scholarly literature and key studies to establish a foundation for the chapter and gain a comprehensive understanding of three main areas: the current critiques of the school report card, the dominant contextual factors influencing academic performance, and existing studies on learners’ ePortfolios.

Studies on the Critique of the School Report Card

Traditional report cards have long been criticised for their narrow focus on academic achievement, often represented by static grades that fail to account for a learner’s broader developmental context. Anderson (2018) argues that grades can become internalised by learners as fixed labels, becoming part of their identity and limiting their self-perception. This view is echoed by Butler (2025), who warns that traditional grading systems often foster competition, pressure, and dissatisfaction amongst students who associate academic results with self-worth. Paramole and Adeoya (2024) further critique this standardised grading practice, asserting that they offer no explanatory insight into how or why a learner achieved a particular result. Taken together, these scholars suggest that the report card not only provides an incomplete picture of a learner’s ability but also risks psychological harm when used out of context. Viewed through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977), these critiques highlight how systems, such as the microsystem (including the classroom environment) and the mesosystem (interactions between home and school), are often omitted from the report card, despite their significant influence on learning outcomes.

Post-Pandemic Studies on Factors Influencing Academic Performance

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified many of the contextual challenges faced by learners, making it urgent to reconsider the way academic performance is measured. As discussed earlier, studies have shown that learners from underprivileged communities lost nearly 60% of their contact teaching time, with many schools lacking the infrastructure for online learning (UNICEF, 2021). These disruptions not only reflect the failures of the exosystem, such as inadequate policy support and resource distribution, but also reinforce the disparities embedded in the macrosystem, including structural inequalities and socio-economic pressures. Furthermore, scholars such as Haffejee et al. (2024) and Mazrekaj and De Witte (2023) have drawn attention to the mental health consequences of school closures, including anxiety, trauma, and depression. These findings underscore the urgent need for educational tools such as learner ePortfolios that can document and respond to such influences in a way that static report cards cannot. The integration of these factors into learner evaluation represents a practical application of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977), emphasising that learning occurs within a nested set of interrelated environments. Moreover, an ePortfolio as such, designed by and grounded in theory, carries vast potential to transform the scholastic reporting process through enabling a deeper understanding of a learner, thus creating an opportunity for personalised support and timely intervention to occur.

Studies on Learner ePortfolios

Numerous authors have shown that ePortfolios can cater for input from multiple role players, allowing for feedback from teachers, parents, and learners and catering for a broader, more holistic representation of a learner’s progress (Bedel et al., 2024; Borthwick, 2021; Doğan et al., 2024). Hence, the ePortfolio at the microsystemic level allows for multiple perspectives to be incorporated, rather than being limited to teacher-generated grades.

Building on the ePortfolio’s multi-faceted input capabilities, both Doğan et al. (2024) and Ayaz and Gök (2022) found that ePortfolios enhance collaboration and communication between players in the learner’s mesosystem. This engagement allows for real-time communication between home and school, ensuring that educators and families collaborate effectively to support the learner. Scholars such as Bedel et al. (2024) and Hsieh et al. (2024) have proved that not only can ePortfolios store large volumes of information, but they can also securely store and manage this documentation for an unlimited period. This relates directly to the chronosystem, allowing for learner progress to be tracked longitudinally rather than being represented as isolated academic scores, thereby enabling educators and parents to identify developmental trends over time and providing a more accurate, adaptive approach to academic support and intervention. This indicates that through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977), the ePortfolio can widen the context of the report card, allowing for multifaceted input of various components and characteristics that influence a child’s learning.

Gaps in ePortfolio Studies Related to Holistic Reporting

While these studies have highlighted the beneficial uses of the ePortfolio, none have examined and included the contextual factors that influence academic performance. Some studies mention that personalised academic artefacts are embedded in ePortfolios, for example, the storage and display of learners’ progress and scholastic achievements, as in Doğan et al.’s (2024) investigation, in which they serve as a collection of school artefacts in the form of a digital and cost-effective storage base; in Majola’s (2025) study; even serving as a unique storage system of a learner’s work, fostering student autonomy, as in Ayaz and Gök’s (2022) case study. However, no ePortfolio studies have included contextual information about the lived experiences or occurrences of the learner. This reveals that qualitative information about the learner was not included or considered in these ePortfolios.

This chapter provides specific contextual design characteristics that are anchored in Bronfenbrenner’s theory for an ePortfolio that serves as a developmental and holistic report card. The chapter reveals how Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory was practically applied to the design of an ePortfolio, indicating how theory informed this practical, innovative intervention. It therefore bridges the gap of static report cards identified in the literature, challenges the existing research, and advocates for the integration of contextual factors into traditional grading practices.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977), a comprehensive model of the data, explaining how multiple environmental layers (systems) interact to influence a child’s development and learning, is provided. Moreover, this section explores the integration between the five theoretical systems and their practical application in the design of an ePortfolio. This approach emphasises the need for school report cards to incorporate the various factors influencing academic performance, thereby ensuring a more inclusive and developmentally supportive reporting approach.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model

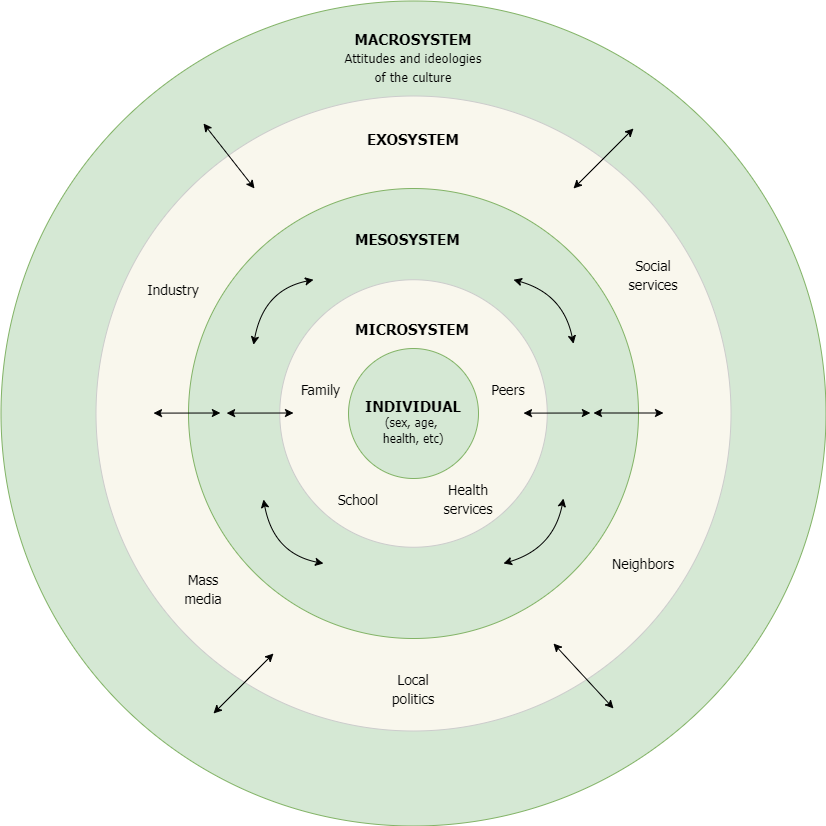

Bronfenbrenner (1977–2005) (Figure 1) is considered one of the major developmental theorists in the role of environmental context on child development and learning (Woolfolk, 2014). Sekhothe (2024) reports that although the idea had been acknowledged that contextual factors influence a child’s development and learning, Bronfenbrenner was the first person to generate an inclusive theoretical model that focuses on the child’s surrounding environment. His model captures all the factors located within a child’s context which influence their development and learning (Crawford, 2020; Sekhothe, 2024).

Figure 1

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model

In this research, “context” refers to the “internal and external circumstances and situations that interact with the individual’s thoughts, feelings, and actions to shape development and learning” (Woolfolk, 2014, p. 89). Bronfenbrenner divides a child’s context into five different systems, namely the microsystem, mesosystem, macrosystem, exosystem, and chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner, 1977), each with a complex relationship to the child and each other. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977) provides a robust framework to enhance understanding and guide the design of a developmental ePortfolio.

Microsystem: This inner system includes those influences that are closest to the learner and have an immediate relationship with them (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Sekhothe (2024) states that these direct relationships include family, peers, teachers, and neighbours. As these relationships are the most important component of all the systems (Bronfenbrenner, 1977), embedding this system and the factors that fall within it into the ePortfolio is essential. Based on its digital capabilities, an ePortfolio has the potential to integrate input from multiple role players, allowing parent and learner contributions, reflections, and feedback to be recorded, thus ensuring holistic microsystem integration.

Mesosystem: This system includes the different relationships between the components of the microsystem, also known as “relations between settings” (Bronfenbrenner, 1977, p. 10). Bronfenbrenner (1977) explains that the mesosystem is created or extended when the individual enters a new setting and an interconnection takes place, for example, in the relationship between the parent and the teacher of that child (Perera, 2023). This interrelationship could be augmented through the ePortfolio, allowing for all communication and collaboration records to be stored and enabling this documentation to be referred to and reflected on at any time.

Exosystem: The third system speaks to one or more settings that do not involve the learner actively, but in which events occur that affect the setting containing the learner (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). The components in this system influence the learner’s development by interacting with a component from their microsystem (Paquette & Ryan, 2001; Perera, 2023). For example, the parents’ working schedule would influence the child (Perera, 2023). Paquette and Ryan (2001) elaborate by explaining that even though the learner is not directly involved with the parents’ workplace, they will feel the negative effects of their parents working late through reduced time for family interaction and less availability to assist with schoolwork. This exosystemic category, consisting of sensitive information, could form part of a separate component on the ePortfolio, with access granted to certain role players. This would allow for contextual factors, such as the parents’ employment status or access to technological support resources at home, to be included in the ePortfolio, moving beyond mere classroom observations and static grades.

Macrosystem: This is the outer layer of the learner’s environment (Berk, 2000), which includes the “larger society,” consisting of cultural beliefs, politics, law, and societal standards (Woolfolk, 2014, p. 91). Despite these components not directly affecting the learner, an indirect influence still takes place. Perera (2023) provides an example by stating that if societal norms dictate that the parents are expected to provide for their child, it is less likely that support and free resources will be provided to the parents by the government. Reflecting on the current social and economic conditions that indirectly affect the learner, in a similar manner to the exosystem, these can be confidentially embedded into the ePortfolio. For example, indicating the parents’ ability to provide and care for their child will ultimately affect that child’s academic results, either enhancing or hindering their performance, and should, therefore, be reflected in a developmental ePortfolio (Paquette & Ryan, 2001).

Chronosystem: This system is centred around the time that passes as the child ages and develops and “focuses around a life transition” (Bronfenbrenner, 1986, p. 724). This includes events such as the death of a parent, the physiological changes that transpire as the learner ages, or the birth of a sibling (Crawford, 2020). The ePortfolio is suited to the chronosystem in its ability to chronologically store information and capture all forms of data entries, allowing for the learner’s school journey to be tracked over time. In this regard, the COVID-19 pandemic serves as a historical event, but more importantly, the ePortfolio would indicate when in the learner’s school career this event took place and how this event impacted their performance and social and emotional well-being. This allows for a deeper and more holistic understanding of the learner by developmentally capturing their scholastic journey over time.

As depicted in Figure 1, the developing person (learner) is at the centre of the diagram, surrounded by an expanding set of systems (Grace et al., 2017). Bronfenbrenner’s theoretical approach declares that factors located within each of these different systems have a direct or indirect effect on a learner’s learning and, ultimately, on their academic performance (Alias et al., 2024; Mtonjeni, 2020; Sekhothe, 2024). The ePortfolio has the potential to embed Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977) into its design and structure, allowing for its contents to developmentally and holistically reflect a learner’s performance and learning. This speaks to the title of the chapter, arguing for a shift from traditional school report cards to developmental and learner-centred ePortfolios using the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977).

Relevance of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

The contradiction must be highlighted that despite the many complex factors that influence academic performance and Bronfenbrenner’s theory arguing that contextual factors affect academic performance, the current school report card provides only a surface-level reflection that comments on academic achievement and takes no written cognisance of these significant factors (Department of Basic Education, 2012). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977) highlights the essential requirement for a developmental method that evaluates learners’ academic progress. The theory posits that a genuinely developmental report card should not only depict static scores but also take into account the complex interactions between the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. Therefore, this framework is not only suited in theoretically confirming the identified limitation of the school report card, but in its ability to practically contribute toward the proposed intervention, being an ePortfolio, by embedding the five systems and factors within as its core design characteristics.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

An exploratory case study approach was employed, which identified the qualitative characteristics of a learner that should be included to generate a holistic learner ePortfolio according to Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977). The case study method is beneficial when detailed knowledge and opinions are required from the selected participants, as in this case study, to develop an understanding of what needs to be included in a holistic ePortfolio (Hofstee, 2011).

Purposive non-probability sampling was used. Babbie and Mouton (2001) explain that in non-probability sampling, the participants are selected based on their relevance and potential contribution to the research topic to gain an in-depth and thorough understanding. For this research, the participants were experts by qualification and were knowingly selected based on their knowledge, experience, and expertise. Furthermore, the participants were chosen based on their location within Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model (1977). The five participants identified for this investigation included an educator, an educational psychologist, an occupational therapist, an inclusive education specialist, and a parent (mother).

Data collection

The structured interview was the chosen data collection tool, based on its ability to gather an individual’s opinion, thoughts, and experiences (Alamri, 2019).

The ultimate purpose of educational research is to improve the lives of human beings (Hostetler, 2005), and thus ethics have become a core component of this research (Ramrathan et al., 2017). Ramrathan et al. (2017) argue that it is the researcher’s responsibility to ensure full confidentiality and protection of all of their participants. In this research, ethical precautions were taken to ensure the protection and safety of the participants. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Cape Town’s Ethics Committee. A consent form was then printed and signed by each participant. It included a description and the purpose of the study and a request to have the audio of their interviews recorded, and it informed the participants of their ability to withdraw from the study at any time. To ensure confidentiality, all the participants were given pseudonyms to guard against their identities being recognised. Only the authorised researchers had access to view the data in its raw form. A date and time were set with each participant to conduct the interview. Lastly, once the interviews were conducted, the recordings were stored on a password-protected hard drive.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis is often open to interpretation while keeping in mind the intention to understand the participants’ world through their perspective and experiences (Babbie & Mouton, 2001). In this research, both a deductive and inductive analysis were used for the identification of common themes across the raw data (Creswell, 2013). Creswell (2013:65) explains that researchers in qualitative research “collect data in natural settings with a sensitivity to the people under study, and they analyse their data both inductively and deductively to establish patterns or themes.” This approach was deemed relevant and appropriate, as not only were common themes identified across the raw data, but these themes were then systematically structured and analysed further into the different systems of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model. The interviews were directly transcribed from the recordings. The transcription of each participant’s interview was grouped and analysed through the lens of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977) by extracting themes and organising them within the five different systems, namely the microsystem, mesosystem, macrosystem, exosystem, and chronosystem.

FINDINGS

The findings from this analysis indicated that 18 factors could be extracted from the transcriptions of the five participants and were able to be located in each of the systems of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977). Each factor has been presented and discussed below in relation to their relevant system.

The Microsystem

Based on the analysis of the participants’ answers, six predominant factors were highlighted in the microsystem: parental divorce, learner-parent relationship, peer relationships, mental health, learning barriers, and soft skills. It was noted that not only were the majority of these factors emphasised by more than one participant, but many of these factors overlapped one another, as seen in Extract 1.1.

Extract 1.1

Educator: Um, because a kid that is struggling with mental health issues is not going to be focusing on what’s actually being taught in class … what they feeling and the emotional state of mind definitely affects the learning in class.

Educational Psychologist: Hugely. I think if a child is emotionally not in a good space, it’s impossible for them to focus on any schoolwork … And that just shows you that’s emotionally when someone is not okay, they actually can’t function in the classroom, and they actually zone out.

In another example, the educational psychologist spoke about how the relationship between the child and their parents and the parents’ academic expectations of their child caused the child to develop an emotional barrier. It could, therefore, be suggested that the factors within the microsystem cannot be holistically analysed and understood in isolation.

The Mesosystem

One can identify this type of interconnection as multi-setting participation, as the child participates in both the school and the home setting (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). An indication of how these two settings have connected is in Extract 1.2, in which the Educator explains that gaining an understanding of the supervision and assistance a learner receives at home creates an opportunity for more empathy, encouragement, and support to occur at school.

Extract 1.2

Educator: I think that understanding where the child comes from is going to assist you in your way that you approach your teaching towards them … So that’s the one thing is having a, having an understanding of what the support base is at home can definitely affect your learning, so teaching styles … I, for example, kids that I know have don’t have assistance at home. I ended up taking on a role of a teacher and a mother, and I’d try and assist in both ways.

Based on the analysis, two factors in the mesosystem were identified as crucial components to a holistic ePortfolio. The first was a communication platform which advocated for the importance of collaboration and communication. The second was parental involvement in schoolwork. It can be suggested that these two factors illustrate the interconnections between a learner’s various settings (contexts).

The Exosystem

Two factors were identified in the exosystem, that is, parental working hours and the socio-economic status of the family. The significance of the exosystem can be seen in how the factors identified in this system had a substantial effect on a learner and their academic performance, as seen in Extract 1.3.

Extract 1.3

Inclusive Education Specialist: Both parents are working nowadays, it’s often the scenario, the mom is not at home anymore. So basically, mom’s coming home from work [saying], “Have you done your homework? Do your homework.” There’s a fight about homework.

Occupational Therapist: “Yeah, huge because if they don’t have, um, the, the resources to do it, it’s, two-fold. One, they don’t provide the opportunities. So, they’re more at risk for, for getting developmental difficulties or having developmental difficulties or challenges or barriers to learning. And two, then when they do have those barriers to learning, they, they can’t access. And then the, the is, you know, there is government routes they can go, but usually the waiting lists for those places are really, really long… Um, and if they’re lower socio-economic status, then the parents aren’t going to be able to dedicate enough time because they’re probably working themselves. So yeah, definitely has a huge impact.

Educator: If you really have struggled not to do your homework because your electricity ran out and mom wasn’t there and there wasn’t light…

Furthermore, this significance occurs to such an extent that these factors could have served as either an advantage or disadvantage to the learner’s scholastic journey and academic performance, demonstrating the importance of the exosystem. It can thus be seen that factors in the exosystem could have influenced not only the learner’s learning and academic performance, but also hindered or promoted their academic success.

The Macrosystem

The significance of the macrosystem lies in people’s shared common identity (Rosa & Tudge, 2013). The family’s value system in the macrosystem identifies the expected values, beliefs, and practices to be followed by members of the family, including the learner. The inclusive education specialist, educator, and educational psychologist were asked whether they believed that a learner’s culture and religion could influence their academic performance. All three participants agreed that a learner’s cultural beliefs do have an influence on academic performance. The educator mentioned that it was not necessarily their belief system, but rather their family morals and values that could provide a child with a strong, stable family foundation. An unforeseen response was given by the inclusive education specialist, who stated that high family morals could serve as either a negative or positive influence, depending on the academic expectations set by the family, as seen in Extract 1.4.

Extract 1.4

Inclusive Education Specialist: It could, but it could definitely work both ways, and it could influence a child negatively because they always trying to live up to something or achieve something or be who the family wants them to be. And they’re not that person. So, if it’s a very religious or culturally-based family, it could have a negative impact. And in our family, we all, um, this is the culture of the family, and we all high achievers … And also, children who have been brought up in a, almost like a very narrow parameters, could struggle to adapt socially in a classroom because they don’t accept other people’s views, [there is a] lack of empathy from the child about other children, you know, um, they different to the other children. So, it could work like that.

The Chronosystem

The analysis of the participants’ transcriptions indicated seven factors that fell within the chronosystem: transition from primary to high school, school profile (Learner Profile), prior parental divorce, prior trauma, relocation, bullying, and COVID-19. These events, particularly COVID-19, had consequences that penetrated through all systems of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977) and have, therefore, been placed within the chronosystem, as seen in Extract 1.5.

Extract 1.5

Educator: So the more distracted you become by these things, um, levels of depression or anxiety, anxiety amongst kids – it is excessive at the moment. It’s just, and I think it’s very, um, post-COVID related. That kids haven’t sat still in a classroom for two years. They haven’t had the discipline structure for two years.

The Department of Basic Education (2012) explains that an essential purpose of the Learner Profile is to assist the teacher in the consecutive grade to understand, assist, and respond to the learner more effectively. In this particular study, it was important to understand what the participants would find as useful information to be included on a Learner Profile for future comparison purposes. Based on the interview with the educator, the following factors could be identified as crucial elements to be included on a holistic Learner Profile: whether a child has repeated or failed a year, any form of prior diagnosis (learning and mental health), and any form of impairments. This history could potentially be interpreted as a summary of the learner’s chronosystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model because of how it consists of key events occurring throughout their life and thus relates to the learner’s development over time. It is therefore suggested that these factors filtered through all systems of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977) and often served as an event that occurred in the past but also influenced the learner’s current lived experience.

DISCUSSION

After a review of the relevant literature and detailed interviews with educational experts, according to Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1977), it has been shown that the school report card was not an accurate representation of a learner’s academic abilities and potential. ePortfolios were then explored as a potential solution to representing academic performance as more than a static grade on a report card. The ePortfolio, with its digital capabilities and practical ability to integrate the five theoretical systems of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model, was evident. Moreover, the factors collected from the data could serve as design characteristics of the ePortfolio, allowing one to capture and reflect on each factor whilst ensuring confidentiality. The data analysis based on the respondents not only corroborated the literature on ePortfolios, but exhibited a strong alignment between the theoretical framework, research design, and findings, revealing the relevance of Bronfenbrenner’s theory and affirming the choice of theoretical lens for data analysis. These 18 factors provide a template of the ePortfolio for practical use, whilst ensuring each empirical design characteristic is theoretically grounded. This confirms that what the participants believed had influenced the learner’s academic achievement could be found within the learner’s context. The findings of this investigation not only align with Bronfenbrenner’s theoretical approach also validates its choice of framework in revealing that context is the predominant factor to be considered when trying to understand a learner holistically. As revealed in the findings, a strong alignment between theory, methodology, and results is evident, further emphasising the theoretically anchored nature of this investigation.

Despite these advantageous features of the ePortfolio, integrating such a digital tool into schools in the future could be a collaborative but strenuous task for several reasons, amongst which is the lack of digital literacy skills of all the role players, including teachers, parents, and learners. Schools may also not have the necessary hardware to accommodate each teacher with a device to access and interact with the ePortfolio. Resistance from role players is also an acknowledged reality, as some parents and teachers may feel that the static mark on the report card is the only true indication of scholastic performance (Brookhart & Guskey, 2019). However, regardless of these challenges and in wakening to the consequential impact of COVID-19 on academic performance, the ePortfolio must continue to be explored as a potential post-pandemic replacement to the school report card. With its capabilities to securely include the critical qualitative factors impacting learner performance and overall development, this digital tool, founded on a theoretical basis, could serve as a transformative alternative to the current school report card.

LIMITATIONS

In using a case study design, I was the primary instrument of data collection and analysis. Reflexivity on positionality was essential, and I acknowledged the potential for bias given my prior experience as a primary school teacher. To mitigate this limitation, I employed triangulation across multiple data sources and presented findings transparently. Moreover, I asked each participant comparable questions mapped to Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model, enhancing dependability through cross-case comparison and the identification of common themes within each system. A second limitation was the small sample size, rather than generalise, I aimed for depth and rich, participant-specific insight, while noting that future research should use larger samples. A final limitation concerns the challenge of replacing the school report card with personalised ePortfolios, including issues of standardisation and implementation that may disrupt practice and invite resistance; nonetheless, this shift remains significant for transforming the traditional reporting system toward a learner-centred, holistic, and developmental approach.

CONCLUSION

The significance of this chapter lies in its outlining of an ePortfolio that can be used to adjudicate a child’s attainment in school in a more holistic manner than the current school report card. To determine what this holistic ePortfolio would consist of, structured interviews were conducted with specialists, with 18 factors emerging from the data. The analysed data advocates that all systems within Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory are critical in order to gain a holistic view of a learner. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provided an ideal theoretical basis for this research, as it closely corresponds to the fundamental notions of holistic, learner-focused educationMoreover, Bronfenbrenner’s framework anchored the practical design characteristics of the ePortfolio in explicitly integrating the five systems and the factors found within each system. Therefore, in contrast to conventional reporting models that show separate academic scores, this framework highlights the interconnected relationships between individual learners and their surrounding environments within real-world contexts. As such, the 18 factors, proposed as the design characteristics for a developmental ePortfolio, directly address the identified shortcomings of the traditional, outdated approach to scholastic reporting, in including factors located within each of the learner’s systems.

The COVID-19 pandemic left learners with unaddressed traumas and substantial knowledge gaps, placing many at academic risk (UNICEF, 2021). To gain a true representation of these types of lived experiences and their impact on academic performance, a holistic representation of a learner is needed. This would allow for targeted interventions and the activated support structures needed by the learner to be implemented by multiple stakeholders. This chapter, therefore, justifies the urgent need for a shift from the traditional school report card to ePortfolios and also provides the first stage of an ePortfolio design on the road to full implementation. The unique contribution of this chapter lies in its provision of 18 explicit design characteristics that are theoretically grounded to be featured in an ePortfolio, as well as the systemic-structural components, such as multifaceted input. It is acknowledged that many factors influence academic performance, and this research may not have covered the exhaustive list of such themes. This presents an opportunity for future research to build upon the foundational work presented in this chapter by potentially using different methodologies or larger sample sizes. Future research also may seek to test the implementation of such an ePortfolio, where addressing the previously mentioned challenges, such as through digital literacy training and educational workshops for parents, could be considered. In summary, this chapter motivates for a shift from the traditional school report card to a holistic learner ePortfolio that has endless capabilities in assisting the transformation of scholastic reporting practices by contributing the design characteristics of a theoretically rooted, developmental ePortfolio that opens the doors to greater understanding, support, intervention, collaboration, and personalised learning.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. I would like to thank my M.Ed. supervisor, Professor Joanne Hardman, for her guidance throughout the course of my qualification. I am also deeply grateful to Professor Belqes Al-Sowaidi for her unwavering support and insightful guidance during this scholarly journey.

REFERENCES

Alamri, W. A. (2019). Effectiveness of qualitative research methods: Interviews and diaries. International Journal of English and Cultural Studies, 2(1), 65-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/ijecs.v2i1.4302

Alias, N. Z., Abdullah Kamal, S. S. L., & Ginanto, D. E. (2024). Theoretical Perspectives on Parental Involvement in Children’s ESL Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Southeast Asia Early Childhood Journal, 13(2), 132–148. https://doi.org/10.37134/saecj.vol13.2.10.2024

Anderson, L. W. (2018). A critique of grading: Policies, practices, and technical matters. Education Policy Analysis Archives. 26(49). http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3814

Ayaz, M., & Gök, B. (2022). The effect of e-portfolio application on reflective thinking and learning motivation of primary school teacher candidates. Current Psychology, 42(35), 31646–31662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04135-2

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J. (2001). The practice of social research. (South African ed.). ISBN: 0195718542, 9780195718546.

Bedel, E. F., İnce, S., & Başalev Acar, S. (2024). Voices from the field: Integrating e-portfolios in early childhood education. Education and Information Technologies, 29(14), 18181–18201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12563-9

Berk, L. (2000). Child development (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Borthwick, H. M. (2021). Curated carefully: Shifting pedagogies through e-portfolio use in elementary classrooms [Master’s dissertation, University of British Columbia]. http://hdl.handle.net/2429/79696

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Development Psychology, 22(6), 723-742. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

Brookhart, S. M. & Guskey, T. R. (2019). What we know about grading: What works, what doesn’t, and what’s next. ASCD. ISBN: 978-1-4166-2723-4.

Butler, M. (2025). Alternative grading systems and student outcomes: A comparative analysis of motivation, enjoyment, engagement, stress, and perceptions of final grades. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 50(5), 807–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2475068

Callens, J. C. & Elen, J. (2007, September 26-28). Purpose and design of an ePortfolio. Conference ICL2007, Villach, Austria. https://telearn.hal.science/hal-00257151

Costa, A., Moreira, D., Casanova, J., Azevedo, Â., Gonçalves, A., Oliveira, Í., Azevedo, R., & Dias, P. C. (2024). Determinants of academic achievement from the middle to secondary school education: A systematic review. Social Psychology of Education, 27(6), 3533–3572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-024-09941-z

Crawford, M. (2020). Ecological Systems Theory: Exploring the Development of the Theoretical Framework as Conceived by Bronfenbrenner. Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100170

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. ISBN: 9781412995313.

Department of Basic Education (DBE). (2012). National Protocol for Assessment Grades 1-12. Department of Basic Education, South Africa. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Policies/NatProtAssess.pdf

Doğan, Y., Yıldırım, N. T., & Batdı, V. (2024). Effectiveness of portfolio assessment in primary education: A multi-complementary research approach. Evaluation and Program Planning, 106, 102461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2024.102461

Grace, R., Hayes, A., & Wise, S. (2017). Children, families and communities: Child development in context. (3rd ed.). ISBN: 9780190304461.

Guy-Evans, O. (2025). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/bronfenbrenner.html

Haffejee, S., Simelane, T.M. & Mwanda, A. (2024). South African COVID-19 school closures: Impact on children and families. South African Journal of Childhood Education 14(1), a1415. https://doi.org/10.4102/ sajce.v14i1.1415

Hofstee, E. (2011). Constructing a good dissertation: A practical guide to finishing a master’s, MBA or PhD on Schedule. EPE. ISBN: 0-9585007-1-1.

Hostetler, K. (2005). What is ”good” education research? Educational Researcher, 34(6), 16-21. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034006016

Hsieh, Y.-H., Yan, J.-Y., Liao, C.-H., & Yuan, S.-M. (2024). Self-Sovereign Identity-Based E-Portfolio Ecosystem. Applied Sciences, 14(22), 10361. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210361

Kingsbury, I., Marshall, D. T., & Doak, C. M. (2025). Making the Grade: Parent Perceptions of A–F School Report Card Grade Accountability Regimes in the United States. Education Sciences, 15(7), 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070885

Kok, I. & Blignaut, S. (2009). Introducing developing teacher-students in a developing context to e-portfolios [Paper, North-West University]. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/introducing-developing-teacher-students-in-a-to-kok-Blignaut/ad7afa1c16b5c8950d353233ae3584c736a0298a

Majola, M. X. (2025). A Proposed Framework For E-portfolio Use to Enhance Teaching and Learning: Process E-portfolio. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 11(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.11.1.63

Mazrekaj, D., & De Witte, K. (2023). The Impact of School Closures on Learning and Mental Health of Children: Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 19(4), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231181108

Mtonjeni, M. C. (2020). An investigation into teachers’ abilities to engage parents of learners to assist their children with learning difficulties. [PhD thesis, University of the Western Cape]. https://uwcscholar.uwc.ac.za/bitstreams/6d8c5e4a-22d0-4779-a48c-df4d71216b05/download

Neuhaus, T., & Jacobsen, M. (2022). The Troubled History of Grades and Grading: A Historical Comparison of Germany and the United States. Formazione & Insegnamento, 20(3), 588–601. https://doi.org/10.7346/-fei-XX-03-22_40

Pallitt, N., Strydom, S. & Ivala, E. (2015). CILT position paper: ePortfolios. CILT, University of Cape Town. http://hdl.handle.net/11427/14039

Paquette, D., & Ryan, J. (2001). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. [Paper] https://dropoutprevention.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/07/paquetteryanwebquest_20091110.pdf

Paramole, O. C., & Adeoye, M. A. (2024). Reassessing standardized tests: Evaluating their effectiveness in school performance measurement. Curricula: Journal of Curriculum Development, 3(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.17509/curricula.v3i2.74535

Perera, K. D. R. L. J. (2023). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory and student motivation. Proceeding of the Open University Research Sessions.

Ramrathan, L., le Grange, L., & Shawa, L. B. (2017). Ethics in educational research. In L. Ramtharan, L. Le Grange, & P. Higgs (Eds.), Education studies for initial teacher development (pp. 432-443). Juta. ISBN: 9781485102663.

Rosa, E.M. & Tudge, J.R.H. (2013). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory of human development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 5(6): 243-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12022

Schneider, Y. T. & Hutt, E. (2014). Making the grade: A history of the A-F marking scheme. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(2), 201-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.790480

Sekhothe, T. C. (2024). The influence of the Ecological Systems on Grade Seven Academic Achievers at a Junior Secondary Township School [Master’s dissertation, University of South Africa]. https://hdl.handle.net/10500/31773

Statistics South Africa. (2020). COVID-19 and barriers to participation in education in South Africa, 2020. Statistics South Africa. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-92-01-08/Final_Final_COVID-19%20and%20barriers%20to%20participation%20in%20education%20in%20South%20Africa,%202020_23Feb2022.pdf

UNICEF. (2021, 22 July). Learners in South Africa up to one school year behind where they should be. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/press-releases/learners-south-africa-one-school-year-behind-where-they-should-be

Wikipedia Commons. (2022). A figure showing Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory of Development. Retrieved on October 26, 2025, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bronfenbrenner%27s_Ecological_Theory_of_Development.png

Woolfolk, A. (2014). Educational psychology (12th ed.). ISBN: 0132613166, 9780132613163.

Yang, H., & Wong, R. (2024). An In-Depth Literature Review of E-Portfolio Implementation in Higher Education: Steps, Barriers, and Strategies. Issues and Trends in Learning Technologies, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.2458/itlt.5809

AUTHOR

Ms. Amber Clarke is an emerging thought leader in Educational Technology and Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education. She is currently pursuing a PhD in Education at the University of Cape Town (UCT), building on a Master’s degree in Educational Technology from the same university. Amber is the Head of Digital Learning and Technology at Two Oceans Graduate Institute (TOGI), a private distance higher education institution in South Africa. In this leadership role, she drives strategic innovation in digital learning and technology-enhanced teaching practices. Amber has lectured in undergraduate and postgraduate teacher education programmes, covering modules such as Information Communication Technology, Coding and Robotics, and Research Methodology, as well as served as the Foundation Phase Teaching Practice Coordinator. Her research interests lie in Educational and Emerging Technologies, Artificial Intelligence, Distance Education and Digital Literacy. Amber strives to push boundaries and explore innovative, disruptive approaches to how technology can transform teaching, learning, and assessment.

Email: email4amberclarke@gmail.com