5 The Resilience of ePortfolios During and After COVID-19: The Past, Present, and Future

Cathrine Kazunga, Bindura University of Science Education, Zimbabwe

Lytion Chiromo, Reformed Church University, Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

ePortfolios play a vital role in the assessment and evaluation of students’ work in most universities in Southern Africa, especially Zimbabwe, during and after COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on education worldwide, especially on Africa, forcing institutions to rapidly adapt to new methods of teaching and assessment. Among the various tools that emerged as essential during this period, electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) became a cornerstone in maintaining educational continuity. This chapter examines how ePortfolios demonstrated resilience during the pandemic, their evolution in response to the crisis, and how they are likely to shape the future of education. The chapter used qualitative methods using the case of a mid-sized public university in Zimbabwe. The data was elicited through document analysis and structured interviews from twelve participants. The findings revealed that ePortfolios are inherently flexible, allowing students to document their work, reflections, and learning experiences asynchronously. This adaptability was vital during the pandemic when synchronous classes and exams were frequently replaced by independent (asynchronous), online learning. Students could continue their learning while demonstrating their progress in a centralised digital format. For example, a student’s progression in a research project, their thought process, or even a presentation video could be added to an ePortfolio, making the assessment process more holistic and transparent. The findings of the study imply that ePortfolios can serve as a sustainable and flexible assessment tool that supports continuity, transparency, and student-centred learning in both crisis and post-crisis educational contexts.

Keywords: ePortfolios, resilience, COVID-19, teaching and learning, student-centred education

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic marked a significant turning point in global education, exposing vulnerabilities in traditional teaching and assessment systems while accelerating the adoption of digital learning technologies. Among the various innovations that increased in response to these disruptions, electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) proved to be particularly resilient, offering a flexible and learner-centred alternative to conventional forms of assessment (JISC, 2020). As universities transitioned abruptly to remote learning, ePortfolios enabled both students and educators to maintain academic continuity by providing a digital space for documenting learning processes, showcasing competencies, and engaging in reflective practice.

Prior to the pandemic, ePortfolios were primarily valued as tools for performance-based assessment and professional development. There is a growing body of research that highlights the role of ePortfolios in fostering digital literacies and ethical awareness in digital environments. Scholars such as Blair (2013), Yancey (2019), and Slade et al (2019) have explored how ePortfolios serve not only as tools for assessment and reflection but also as platforms for students to develop responsible digital identities, engage critically with technology, and navigate the ethical complexities of online communication. Blair (2013) emphasised the rhetorical and ethical dimensions of composing in digital spaces, while Yancey (2019) examined how ePortfolios contribute to students’ agency in digital self-representation. Similarly, Slade et al. (2019) discussed how ePortfolios can be structured to support both technical proficiency and ethical considerations in digital learning contexts. Together, these works underscore the transformative potential of ePortfolios in cultivating informed, reflective, and ethically engaged digital citizens. However, their role evolved significantly during the crisis. Their asynchronous nature allowed students to manage their learning independently while still receiving feedback and demonstrating growth in a structured and holistic manner (Batson, 2011). This adaptability was not only crucial in navigating the uncertainties of emergency remote education but also in redefining what effective, student-centred assessment could look like in the digital age.

This chapter explores the evolution and sustained relevance of ePortfolios during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. By analysing a case study from a mid-sized public university in Zimbabwe, the study situates its findings within a higher education context marked by limited digital infrastructure, resource constraints, and the urgent need for adaptive teaching and assessment strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. The university, like many in Southern Africa, faced challenges such as inconsistent internet access, limited access to devices for both students and staff, and varying levels of digital literacy. Despite these barriers, the institution adopted ePortfolios as a pragmatic solution to support remote learning and assessment. The university context is thus characterised by resilience and innovation in the face of systemic challenges, highlighting how digital tools like ePortfolios can be leveraged to enhance educational access, engagement, and quality in under-resourced environments. By analysing such a university setting, this chapter highlights how ePortfolios supported academic resilience and reimagined assessment practices and may continue to influence the future of higher education in a post-pandemic world. Accordingly, the research questions that are addressed in this study are:

- How did ePortfolios demonstrate resilience during the pandemic?

- What was their evolution in response to the crisis, and how might they shape the future of education?

LITERATURE REVIEW

The global outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020 triggered a seismic shift in education systems, necessitating a rapid move to digital and remote learning environments. In this context, ePortfolios emerged as a key digital solution for maintaining assessment integrity, promoting student agency, and enabling flexible, asynchronous learning. Their capacity to document student learning journeys in multimodal and reflective formats offered a timely and resilient response to the educational disruptions caused by the pandemic (Zhou & Brown, 2015). To frame this discussion, the following literature review is structured to examine three key areas: first, the pedagogical foundations and evolving definitions of ePortfolios; second, their documented role and effectiveness in digital learning environments prior to and during COVID-19; and third, the specific challenges and opportunities presented by their use in under-resourced higher education contexts, such as those in Southern Africa. This structure is intended to guide the reader through the conceptual and contextual background necessary to understand the case study findings and their broader implications.

Notion of ePortfolios

ePortfolios has many definitions depending on the context in which it is used. An ePortfolio is a digitized collection of artefacts, including demonstrations, resources, and accomplishments that represent an individual’s learning journey over time, often accompanied by reflective commentary that gives context and meaning to the included work (Barrett, 2007). According to Lorenzo and Ittelson (2005), ePortfolios are collections of student work that are stored electronically and can be used to demonstrate learning achievements and competencies over time, often serving both formative and summative assessment purposes. Yancey (2009) defines an ePortfolio as a space for students to collect, select, reflect, and connect their learning experiences, emphasising the role of ePortfolios in fostering student agency and digital identity formation. Stefani, Mason, and Pegler (2007) describe ePortfolios as a purposeful aggregation of digital items, ideas, evidence, reflections, and feedback—demonstrating learning, competence, and achievement, supported by a digital platform that allows for ongoing updates and sharing with multiple audiences. In this chapter ePortfolio is viewed as a purposeful, digital collection of a learner’s work that showcases their skills, knowledge, experiences, and reflections over time. It serves as both a learning and assessment tool, enabling students to document their academic and personal growth, engage in reflective practice, and present their competencies to various audiences in a flexible and multimodal format. It is also a structured, digital collection of pre-service or in-service teachers’ work that documents their professional learning, teaching competencies, and reflective practices over time. It serves as both a formative and summative tool, allowing teacher candidates to demonstrate their development across key areas such as lesson planning, classroom management, assessment literacy, and pedagogical reflection, while fostering a habit of continuous professional growth and self-evaluation.

ePortfolios in Digital Assessment

Prior to the pandemic, ePortfolios were gaining increasing attention for their value in authentic, learner-centred assessment, particularly in higher education and professional training contexts (Barrett, 2010; Eynon, Gambino, & Török, 2014; Cambridge, 2010). The Catalyst for Learning project (Eynon et al., 2014) demonstrated how ePortfolios support integrative learning, reflective practice, and institutional improvement across diverse university settings. Additionally, the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) formally recognised ePortfolios as a High-Impact Practice (HIP), citing their capacity to promote deep learning, student engagement, and evidence-based assessment (Watson, Kuh, Rhodes, Light, & Chen, 2016). These developments positioned ePortfolios as essential tools for bridging academic learning with professional readiness even before the shift to online learning prompted by COVID-19. Unlike traditional tests, ePortfolios allow students to compile evidence of learning, such as project drafts, reflections, presentations, and peer feedback. This performance-based approach to assessment provides a holistic view of student development over time (Chen, 2010). During the pandemic, when proctored exams were often unfeasible, many institutions adopted ePortfolios to evaluate learning outcomes more flexibly and fairly (Nguyen & Habók, 2021).

Flexibility and Continuity During COVID-19

One of the most cited advantages of ePortfolios during the COVID-19 era was their asynchronous flexibility. Students were able to continue their learning independently, using ePortfolios to document progress without being bound to scheduled class times or synchronous exams (Trust & Whalen, 2020). This flexibility was critical in contexts where students faced challenges such as limited internet access, time zone differences, or increased personal responsibilities at home.

Moreover, the resilience of ePortfolios lies in their adaptability across disciplines and learning contexts. Studies show that ePortfolios were used effectively in teacher education (López-Pastor et al., 2020), health sciences (Garrett & Jackson, 2006), and the arts, reflecting their interdisciplinary potential and particular relevance during emergency remote teaching. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, ePortfolios provided a flexible and student-centred alternative to traditional assessment across multiple disciplines, supporting continuity of learning and reflection in disrupted educational contexts (Torres-Hernández & Gil-Fernández, 2021).

Fostering Reflection and Student Agency

Another key dimension of ePortfolios is their emphasis on reflection, which enhances metacognition and deep learning. Reflective practices embedded in ePortfolios help students internalize learning goals, assess their own progress, and develop self-regulatory skills (Yancey, 2009). These attributes were particularly important during the pandemic, when students had to take greater ownership of their learning due to reduced face-to-face interaction with instructors.

Furthermore, ePortfolios promote student voice and agency by enabling students to choose how to present their work, set personal learning goals, and curate digital artefacts that reflect their unique learning trajectories (Buzzetto-More, 2010). This learner autonomy was essential during COVID-19, as students navigated increased uncertainty and educational isolation.

Challenges and Considerations

Despite their strengths, the literature acknowledges several challenges in implementing ePortfolios effectively. These include technological barriers, lack of institutional infrastructure, limited digital literacy among educators and students, time constraints, and inconsistent feedback practices (Hallam & Creagh, 2010; Hallam & Creagh, 2010a; Bennett, Rowley, Dunbar-Hall, Hitchcock, & Blom, 2012; Buyarski & Landis, 2014; LaMagna, 2017; Slade, Murfin, & Readman, 2019). These challenges have been particularly pronounced in contexts where ePortfolio adoption was accelerated by crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, without adequate professional development or systemic support. During the pandemic, these challenges were often amplified by limited digital infrastructure and the urgent need for training and support. Institutions that had pre-existing ePortfolio systems in place were generally more successful in transitioning to online assessment models (Nguyen & Habók, 2021).

The Future of ePortfolios in Post-COVID Education

Post-pandemic, there is growing consensus that ePortfolios will remain a critical tool in reimagining assessment and pedagogy. Researchers and institutions alike have recognised the enduring value of ePortfolios in supporting authentic, student-centred, and flexible approaches to teaching and learning (Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Nguyen & Ikeda, 2021; Reese & Levy, 2009). As higher education shifts toward more holistic and integrative models of assessment, ePortfolios are being positioned not only as repositories of student work but also as platforms for reflective practice, lifelong learning, and professional development (Rowley & Munday, 2018; Slade et al., 2019). Furthermore, the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) continued to promote ePortfolios as a High-Impact Practice (HIP) that advances equity, engagement, and academic success in diverse learning environments (Watson et al., 2016). This convergence of scholarship and policy signals that ePortfolios are not just a temporary response to emergency remote learning but a lasting component of post-pandemic educational transformation. They align well with calls for more personalised, competency-based, and student-driven education (JISC, 2020). As universities seek to build more resilient and equitable education systems, ePortfolios offer a model that integrates academic learning with digital skills, reflection, and real-world relevance.

The literature strongly supports the idea that ePortfolios served as a resilient and effective tool during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering flexible, reflective, and authentic alternatives to traditional assessments. Their adaptability across contexts and alignment with student-centred pedagogy position them as valuable tools not only in times of crisis but also in the ongoing evolution of digital education.

THE E-TEACHING PRACTICE MODEL

The E-Teaching practice Model is being used to assess students during teaching practice at a mid-sized public university in Zimbabwe. “ The E-Teaching Practice is a smart learning systems that communicate and cooperate with student teachers during their work-related practicum period” (Gwizangwe, Mhishi, Zezekwa, Mpofu, Sunzum, Mudzamiri, Manyeredzi, Munakandafa, Chagwiza, Ndemo, Kazunga & Mutambara, 2019, p. 2).

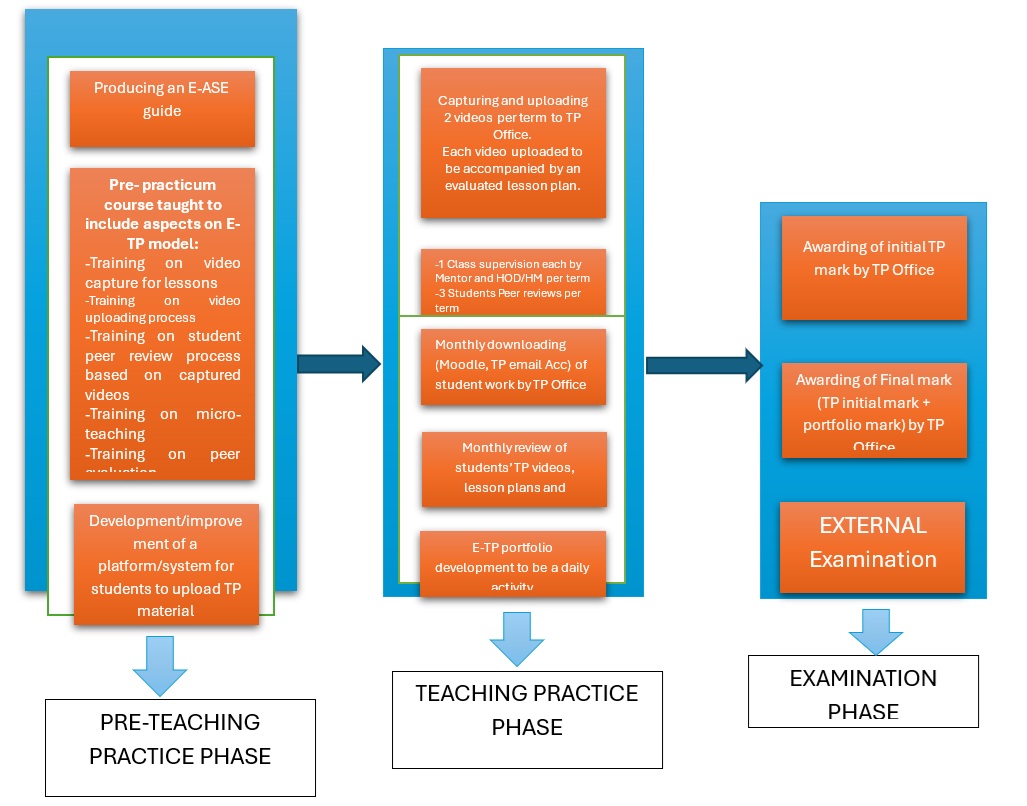

Figure 1

The E-Teaching Practice Model (adopted from Gwizangwe et al., 2019, p. 2)

The E-Teaching Practice model was used in this study to understand the use of ePortfolio in the assessment and evaluation of pre-service science and mathematics student teachers’ learning and teaching while on teaching practice. The E-Teaching Practice model assumes that the pre-service science and mathematics student teachers receive pre-teaching practice preparations. The students are taught aspects of the E-teaching practice model, such as training on video capturing, peer review process based on videos captured, micro-teaching, and peer evaluation (Gwizangwe et al., 2019). The students are introduced to the assessment methods and evaluation methods, such as peer evaluations.

The E-teaching practice model assumes that during teaching practice the pre-service science and mathematics student teachers will upload a video to the teaching practice office accompanied by a peer review assessment and evaluation report. (Gwizangwe et al., 2019). The assessment and evaluation method suggested is the peer review assessment method. In this case the peer assessments and evaluations will be done by the student teacher and the head of department, mentor, and headmaster/mistress of the host school. The student teacher will create an ePortfolio that is going to be submitted to the teaching practice office.

Lastly, the university supervisors and/or teaching practice coordinator will use summative assessment and evaluation as an examination process. Gwizangwe et al. (2019) argued that the examination phase involves a continuous and cumulative process. The school-based and faculty assessments are done and captured on the students’ profiles each term. These contributed to the initial mark. “The initial mark and the ePortfolio mark are combined to give the final mark” (Gwizangwe et al., 2019, p. 4).

Gwizangwe et al. (2019) defined ePortfolio as “the electronic version of the teaching practice file; the ePortfolio has additional components such as lesson videos, electronic reference materials, and cloud backup, among others.” The ePortfolio profiles the student teacher’s teaching and professional development.

The E-teaching practice model assumes that a typical ePortfolio would contain the following generic sections: “timetable, lesson plan, schemes of work, lesson videos, school syllabi, national syllabi, test dossiers, record of marks, practicum assessment records/profile, and practicum hand-outs” (Gwizangwe et al., 2019).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This chapter is grounded in a combination of key educational theories that help explain the role and potential of ePortfolios in assessment and learning, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The selected theories include constructivism, experiential learning, the technology acceptance model (TAM), and the Community of Inquiry Framework (CoI), which offer valuable insights into the resilience, adaptability, and educational value of ePortfolios in the context of higher education.

Constructivism (Vygotsky, 1978; Piaget, 1970)

Constructivist theory, as articulated by Piaget (1970) and Vygotsky (1978), posits that knowledge is actively constructed by students through interaction with their environment, experiences, and social interactions. In the context of ePortfolios, this theory emphasizes that learning is an active, dynamic process where students construct meaning through reflection on their experiences, documentation of their learning process, and engagement with peers and instructors.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when traditional in-person classes were largely replaced by online and hybrid formats, ePortfolios allowed students to continue this process of knowledge construction in an asynchronous and self-directed manner. Students could engage with content, reflect on their understanding, and showcase their learning outcomes, all while maintaining a sense of autonomy over their educational journey. This aligns with Vygotsky’s notion of scaffolding: the support structures provided by ePortfolios (in the form of digital artefacts, feedback, and resources) helped students make meaning of their experiences, especially when face-to-face interactions were minimal. This aligns with Vygotsky’s notion of scaffolding the support structures provided by ePortfolios, in the form of curated digital artefacts, structured feedback, and embedded resources, helped students make meaning of their academic and practical experiences. In the absence of regular face-to-face interaction, students were primarily engaging with asynchronous materials, self-directed tasks, peer feedback, and reflective prompts housed within their ePortfolios, making the platform itself a central site of learning and interaction.

Experiential Learning Theory (Kolb, 1984)

Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) underscores the importance of learning through experience and reflection. According to Kolb (1984), effective learning involves four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation.

In the context of ePortfolios, students engage in this cyclical process by documenting their concrete experiences (e.g., projects, assignments), reflecting on their learning (through written reflections and multimedia), conceptualizing new knowledge, and experimenting with new ideas or revisions to their work. The flexibility of ePortfolios allowed students to move through these stages despite disruptions, ensuring that experiential learning continued even in virtual and remote environments.

The reflective observation and abstract conceptualization components are particularly vital during the pandemic, as students could revisit their learning progress, adapt to new learning modalities, and critically assess their own learning strategies. The ePortfolio, as a tool for documenting this process, provided a central repository for these learning stages.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989)

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) is widely used to explain the factors influencing the acceptance and use of new technologies, particularly in educational contexts. According to TAM, two primary factors influence technology adoption:Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). In the context of ePortfolios, Perceived Usefulness refers to the degree to which students and educators believe ePortfolios enhance learning and assessment. During the pandemic, ePortfolios proved useful for continuing learning activities when face-to-face teaching was not feasible. Their role in facilitating asynchronous assessments, documenting learning, and fostering reflection was considered highly beneficial. Their role in facilitating asynchronous assessments, documenting learning, and fostering reflection was considered highly beneficial (Chen et al., 2021; Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Batson, 2010). ePortfolios have been shown to support independent, self-paced learning while encouraging students to engage in deeper reflection and meaning-making, especially in contexts where real-time interaction is limited.

Perceived Ease of Use, on the other hand, refers to how easy and user-friendly the ePortfolio platform is for both students and educators. This factor becomes especially critical in times of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, when there was little opportunity for extensive training or technical support. The ability of users to quickly navigate and make effective use of ePortfolio tools significantly influenced adoption and sustained engagement. As Eynon and Gambino (2017) emphasize in High-Impact ePortfolio Practice, technical infrastructure and platform usability are foundational to successful implementation; without them, even the most pedagogically sound ePortfolio initiatives can falter. Similarly, contributors to the ePortfolios@EDU collection (Thanos & Nagelhout, 2023) highlight that inconsistent or poorly supported platforms can lead to frustration, diminished reflection, and unequal learning experiences. Thus, technology is not a neutral background but an active factor in shaping the success of ePortfolio practices, particularly in emergency remote teaching environments. TAM provides a lens through which the adoption and success of ePortfolios during and after the COVID-19 pandemic can be understood, considering both their educational value and user-friendliness.

Community of Inquiry Framework (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000)

The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework underpins meaningful learning in online environments by identifying three essential presences—cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence—that jointly foster deep and collaborative learning experiences (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000a). Cognitive presence refers to learners’ ability to construct meaning through reflection and critical thinking. ePortfolios visibly support this presence by enabling students to document their learning journeys, reflect thoughtfully, and engage in sustained inquiry (Zhang & Tur, 2023). Social presence speaks to learners’ capacity to project their personal identities, emotions, and intentions into a shared learning space. Collaborative ePortfolios where students exchange feedback, co-create artefacts, and engage in group tasks strengthen this presence, helping to maintain a sense of community even in remote contexts (Zhang & Tur, 2023). Teaching presence encompasses the design, facilitation, and guidance provided by educators to orchestrate both cognitive and social processes toward learning outcomes. In ePortfolio-based learning, instructors scaffold the experience by offering structured prompts, timely and constructive feedback, clear rubrics, and guidance thus shaping and sustaining meaningful learner engagement (Zhang & Tur, 2023)

Drawing on Constructivism, Experiential Learning, Technology Acceptance, and Community of Inquiry, this study establishes a comprehensive theoretical foundation for understanding how ePortfolios contributed to educational resilience during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. These frameworks illustrate how ePortfolios function as tools of reflection, student agency, and collaborative learning, enabling learning to persist even amid disruption. Additionally, the flexible and multimodal nature of ePortfolios aligns with these theoretical perspectives, supporting a wide range of learning activities and outcomes across both synchronous and asynchronous modalities (Zhang & Tur, 2023)

METHODOLOGY

This chapter employed a qualitative case study approach to explore the use and adaptability of ePortfolios during and after the COVID-19 pandemic in a higher education context. The qualitative paradigm was chosen for its ability to provide rich, in-depth insights into participants’ lived experiences, perceptions, and practices in relation to ePortfolio use (Creswell, 2013).

Research Design

This study employs a single-case study design, focusing on a single university that had implemented ePortfolios before, during, and after the COVID‑19 pandemic. This approach allows for an in-depth exploration of how the institution adapted its assessment and teaching practices using ePortfolios within its unique real-life context, illustrating the continuity and evolution of digital assessment practices over time (Yin, 2018). Drawing on Yin’s methodology for case study research, the study leverages qualitative methods to investigate the institution’s adaptation process. Structured interviews were conducted to gather data from key stakeholders—students, educators, and administrators on their experiences and perceptions of ePortfolio usage during these distinct periods. The interviews were done during students’ free time. The students were doing their final year after one year of teaching practice. They all had diplomas in science education. Ethical approval was obtained from the university’s research ethics board. All participants were provided with informed consent forms outlining the purpose of the study, confidentiality measures, and their right to withdraw at any point. Data were anonymised, and all digital files were securely stored. Participants provided informed consent, and confidentiality protocols were upheld, mirroring standard practice in reflective portfolio research. The students were labelled S1, S2 to S10 for anonymity; S1 means student 1, and the lecturers were labelled L1 and L2; L1 means lecturer 1.

Participants

The participants include two lecturers and ten students. The two lecturers are faculty members from Science and Mathematics department, responsible for guiding the final year teaching practice. One lecturer specialised in Mathematics Education, while the other specialised in Geography Education. Both have experience supervising student teachers and evaluating ePortfolios.The ten students are all final-year Diploma in Science Education candidates following a one-year teaching practice placement.The discipline areas for students were placed in local secondary schools teaching subjects such as, Agriculture, Mathematic, Combine Science, and Mathematics. All students compiled similar ePortfolios structured around their teaching practice using the E-Teaching Practice model requirement (see Figure 1). This included lesson plans, schemes of work, videos captured for the lesson, and reflective journals from the mentor or head of department or head or school. All housed within a shared template or platform across one cohort. From the ten students, six were female students and four were male students. With ages ranging from 21 to 25 years. All had completed core science teaching coursework prior to their teaching practice. The students were teaching Mathematics, Science and Agriculture offering insight into the content and challenges reflected in their ePortfolios. All students completed the same kind of ePortfolio in the same context. The 12 participants, including 2 lecturers and 10 students from the same faculty, used ePortfolios as part of their academic activities. Academic activities encompass all teaching and learning-related engagements that students undertake both inside and outside the classroom as part of their formal education. These activities are often initiated by educators and may include classroom interactions and participation, assignments, reading, and projects. work, seminars, discussions, study groups, and exam preparation, engagement with learning platforms, fieldwork, work placements, and experiential learning settings. The students were doing their final year after one year of teaching practice. They all had diplomas in Science Education. The students complete the same kind of ePortfolios with teaching practice materials. Purposive sampling was used to select participants with direct experience of ePortfolio use during the pandemic. This ensured that the data collected was relevant and informed by first-hand engagement with the technology and its pedagogical application (Patton, 2002).

Data Collection and Data Analysis

The chapter used two main methods to gather data: document analysis and structured interviews. During document analysis, institutional policy, module outline, assessment rubric, and assessment guides were reviewed to understand how ePortfolios were structured and applied before and during the pandemic. We collected multiple types of institutional documents to understand the intended structure, implementation, and evolution of ePortfolios. The institutional policies and governing documents include the E-Teaching Practice Model Administration Manual, assessment regulations, and platform guidelines that structure expectations and constraints around ePortfolio use. The module outlines indicating how and when ePortfolios are integrated, including intended learning outcomes and alignment with pedagogical goals. Assessment guides and rubrics have the criteria for evaluation, feedback structures, and reflection expectations key in revealing how ePortfolios were envisaged as assessment tools. Student ePortfolios as artefacts are primary data sources for reflections and outcomes; these artefacts also function as “documents” reflecting how policy and design were enacted in practice. These artefacts shaped our research framing by highlighting the intended pedagogical scaffolds, enabling comparisons with how ePortfolio usage actually unfolded. Analysing these documents allowed us to identify institutional affordances, expectations, and gaps, serving as a foundation for triangulating with interview data. Data were analysed using thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase process: (1) familiarisation with data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. Codes were generated inductively, allowing themes to emerge from the data rather than being predefined. Emergent themes focused on adaptability, reflection, continuity of learning, digital competence, and institutional support mechanisms.

Documents collected were read as complete artefacts to grasp the overall structure, intent, and pedagogical framing. Small, meaningful units like rubric descriptions, reflective prompts, or policy clauses were coded and analysed for targeted insights.We used thematic analysis, a flexible qualitative method that supports both deductive (theory-driven) and inductive (data-driven) approaches. Thematic analysis allowed the examination of patterns and meaning across data sets, whether relying on pre-existing theory or discovering new themes emerging from the data. Alongside thematic analysis, we employed qualitative content analysis to analyse document content systematically. Deductive content analysis was used to predefine categories, often derived from theory or literature, to code documents. Segments not fitting initial categories were marked for further review. This allowed us to apply theoretical lenses on constructs from CoI frameworks when we were interpreting and categorising document content. Again, inductive content analysis was used; we started with open coding, allowing categories and themes to emerge directly from the data, ideal for exploring phenomena without assuming prior structure.

Table 1

Summary: Integrated Data Analysis Process (created by Authors)

|

Step |

Methodological Approach |

Purpose |

|

Document Collection |

Policies-E-Teaching Practice Model adminstration manual, module outline, rubrics, student ePortfolios |

Capture institutional designs and enacted practices |

|

Familiarization |

Holistic reading of documents |

Understand structure, tone, and intent |

|

Coding |

Deductive (using theoretical categories) |

Map data to existing frameworks and confirm alignment |

|

Coding |

Inductive (open coding for new themes) |

Capture unexpected insights and context-driven patterns |

|

Unit of Analysis |

Segmental (clauses, prompts) and Holistic |

Balance depth and overall coherence |

|

Theme Development |

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke method) |

Identify patterns and synthesize meaning |

|

Triangulation |

Cross-comparing with interview data |

Strengthen validity and enrich findings |

These documents provided contextual information about institutional expectations and support for ePortfolio integration. Each participant took part in a structured interview conducted via WhatsApp audio conferencing. Interviews were guided by a standardized set of open-ended questions that explored the design, use, challenges, and perceived benefits of ePortfolios in the shifting educational landscape. Interviews were recorded with participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim for analysis. The open-ended questions are attached in the Appendix. The students and the educators answered different questions.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The data collected through document analysis and structured interviews revealed several key themes regarding the resilience of ePortfolios during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as their evolution in post-pandemic higher education settings. These themes underscore how ePortfolios adapted to the changing educational landscape, their impact on student learning, and the challenges faced by both university students and lecturers. The major findings are summarized under the following themes: Flexibility in Learning and Assessment, Enhanced Reflection and Self-Directed Learning, Collaborative ePortfolios, and Challenges in Implementation.

Flexibility in Learning and Assessment

A prominent finding from the study was the flexibility that ePortfolios provided in maintaining continuity of learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eight out of ten students highlighted that ePortfolios allowed them to document their learning progress asynchronously, which was particularly important during periods of emergency remote learning. Student 1 has this to say:

“During the pandemic, I could no longer attend lectures in person, but with my ePortfolio, I was able to document what I had learned, submit assignments, and even reflect on the progress I was making. It gave me the flexibility to work at my own pace while still staying on track with the course.” S1

The student emphasised how the ePortfolio supported independent learning by allowing them to document learning, reflect, and submit work asynchronously. This aligns with the idea that ePortfolios enhance self-directed learning strategies, enabling students to set goals, monitor their progress, and adapt based on self-reflection. Post-pandemic research has repeatedly identified ePortfolios as key tools in promoting learner autonomy and self-regulation, especially amid disrupted instructional environments. S1 underscored the ePortfolio’s role in providing flexible access and continuity of learning when traditional classrooms were inaccessible. Students were able to proceed at their own pace while staying aligned with course expectations. A benefit echoed in other studies examining pandemic-era challenges is the flexibility afforded by ePortfolios, which enabled students to organize and engage with their learning materials asynchronously and at their own pace (Abuzaid et al., 2021; Modise & Mudau, 2022). As one investigation into digital portfolios noted, students “had greater control and learning pace in the tasks performed for the attainment of the objectives… the use of space and time during the pandemic had more advantages than before the pandemic.” For instance, OneDrive-supported ePortfolios have been praised for enabling student control and organization of their learning during remote.

Through document analysis of module outlines and institutional policy documents, it was confirmed that ePortfolios were integrated into assessment models to replace traditional examinations, which were difficult to administer during the pandemic. The E-Teaching Practice Model Administration Manual references replacing visits by the lecturer to observe lessons by ePortfolio with lesson plans, schemes of work, video captured for the lesson, and a reflective journal from the mentor or head of department or head of school. These are sent to the institution with a stipulated time frame; see Figure 1. The module outline has instructions outlining ePortfolios as primary assessment methods, with guidance on submission formats, timelines, and criteria adapted for remote contexts. Assessment guides in The E-Teaching Practice Model Administration Manual includes evaluation criteria emphasizing reflective depth, multimodal submission, and process and product, rather than exam performance. May include language clarifying that ePortfolio artefacts substitute for exam-based evidence.

Multimedia was clearly emphasised in the document analysis, particularly in how students were required to include various digital artefacts as evidence of teaching in the E-Teaching Practice model (see Figure 1). Many ePortfolios included video presentations, written scanned reflections, and image-based documentation, for example, photos of projects, diagrams, and infographics. These were often paired with written reflections to deepen metacognitive engagement. The structure of the ePortfolio platforms themselves provided tools for embedding multimedia content directly. This suggests intentional design for multimodal expression emphasizing not just what students learned, but how they chose to represent it. In several analysed documents, such as assessment rubrics, assessment guidelines, and the E-Teaching Practice Model Administration Manual, explicitly called for multimodal submissions. Terms like “visual evidence,” “recorded explanations,” and “interactive media” in the assessment rubric indicated that multimedia was not only encouraged but embedded as a core expectation of reflective practice. Thus multimodal documentation of learning was a key feature that helped students articulate their thought processes and progress in more dynamic and authentic ways, enhancing self-directed learning (Gao et al., 2020). This capability for multifaceted expression during times of remote learning added an element of creativity and personalization to the education process, an advantage often lost in rigid traditional exams or assessments.

Enhanced Reflection and Self-Directed Learning

The ePortfolio’s role in fostering reflection was another significant theme. Both students and lecturers emphasized the importance of reflection in ePortfolios for deep learning and self-assessment. Students were able to reflect on their learning journeys, integrate feedback, and revise their work in a way that traditional assessments could not accommodate. Lecturer 1 explained:

“What I noticed was that students who were using ePortfolios regularly were more reflective about their learning. They were able to document not just their assignments, but their thought processes and how their understanding evolved. It allowed them to take ownership of their learning.” L1

Nine students stated:

“I could carry my phone everywhere. I am able to reflect on what I did in class during the teaching practice. I will take several videos and choose the one that is clear and audible.” S1

“Using the ePortfolio helped me see how my thinking changed over time. I could look back and realize how much I had grown, not just in skills, but in how I approached problems.” S5

“It wasn’t just about uploading my assignments. Writing about why I made certain choices really made me think more deeply about what I was learning.” S6

“Before, I would finish a project and move on. With the ePortfolio, I actually had to pause and think about what I learned and how I got there.” S7

“I started noticing patterns in how I learn best. Reflecting in my ePortfolio made me more aware of my own process.” S8

“It made me feel like I was in charge of my learning. Instead of just doing work for grades, I was building something that showed who I was as a learner.” S9

“I used to hate writing reflections, but the ePortfolio made it feel more personal. I could connect it to my goals and see my progress in a way that made sense to me.” S10

“I liked seeing how my thoughts evolved. What I believed at the start of the semester was really different from what I understood by the end.” S4

“It gave me a chance to explain my thinking, not just show a finished product. That made me care more about what I was doing.” S2

There is evidence that ePortfolio encouraged students to assess their own work and make adjustments in response to feedback. Students used ePortfolios to engage in deep, reflective learning and self-assessment, leading to enhanced metacognitive skills. The study also revealed that ePortfolios played a pivotal role in fostering reflection and self-regulation. Participants noted that the ePortfolio provided a space for deep reflection, where students could assess their own progress, challenges, and insights. This aligns with Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (1984), which emphasised the importance of reflective practice as part of the learning cycle. The ability to continually revisit and revise ePortfolios encouraged students to critically engage with their own learning journeys.

Additionally, ePortfolios facilitated self-directed learning, a crucial skill for lifelong education. Many students reported that they appreciated the autonomy ePortfolios provided them in managing their learning, as they were able to set their own goals, track their progress, and reflect on their achievements over time. This finding is consistent with research on self-regulated learning, which argues that when students take ownership of their learning process, they are more likely to engage meaningfully and persistently in their studies (Zimmerman, 2002).

The process of compiling evidence of learning, especially through multimedia artefacts such as videos, images, and audio reflections, has been shown to significantly enhance students’ self-regulation and critical thinking skills. According to recent educational studies, the act of curating and presenting these artefacts requires students to make intentional decisions about what learning is meaningful and why, encouraging deeper cognitive engagement (Chang, 2019; Cheng & Chau, 2016). This process fosters metacognition, as students must reflect on their learning goals, monitor their progress, and revise their understanding through feedback and iteration. The multimodal nature of digital portfolios also appeals to various learning styles, providing students with flexible ways to express understanding and critique their own work. As one student reflected,

“When I put together my portfolio using videos and voice notes, I had to explain my thinking out loud. That helped me realize what I actually understood and what I just memorized.”

This reflective practice transforms learning from passive task completion into an active, personalised process supporting long-term development of autonomous learning habits.

Three students stated:

“It just felt like another hoop to jump through. I didn’t really see how it helped me learn.”

“Most of the time, I was just uploading stuff because it was required—not because I found it useful.”

“It was confusing to use, and the platform kept glitching. That made it frustrating instead of helpful.”

“There wasn’t enough guidance on how to reflect properly. I didn’t know what I was supposed to say.”

However, it is worth noting that the ability to reflect and self-regulate effectively relies on the metacognitive skills of students. As highlighted by quotes of four participants, not all students were equally adept at using ePortfolios to engage in reflective practice, suggesting that additional guidance and training on critical reflection should be integrated into ePortfolio initiatives to maximise their impact. This indicates that when the reflective element was not meaningfully supported or differentiated from routine submissions, some students felt the process lacked depth and authenticity.

Collaborative ePortfolios

A significant shift during the pandemic was the emphasis on collaborative ePortfolios. While traditional ePortfolios often focused on individual work, several institutions encouraged collaborative projects, where students could document joint work, provide peer feedback, and engage in group reflections. Student 5 described her experience:

“I worked with my classmates on a group project through use audios and video conferencing for the first time using an ePortfolio. It was not just about submitting individual tasks; we all added to the portfolio, shared ideas, and provided feedback to each other. It felt like a community of students even though we weren’t physically together.”

Student 5 mentioned that he worked with her classmates on a group project for the first time using ePortfolio. The group member contributed to the group task. They share ideas and give feedback to each other since it was not just about handing in the individual work. She felt like a community of students even though it was virtual, not physical.

Two lecturers stated:

“Engaging in reflective conversations with peers and mentors can enhance both student learning and collective group performance.” L1

“Talking about our work with workmates and more experienced people helps us get better ourselves and work better as a team.” L2

Two lecturers who were interviewed also noted that these collaborative ePortfolios fostered teamwork and communication skills, which are crucial in professional environments. This might suggest that the collaborative aspect of ePortfolios is an area that has the potential to continue growing post-pandemic, as it encourages peer engagement and co-creation of knowledge. The pandemic encouraged the use of collaborative ePortfolios, which fostered peer interaction and teamwork.

Another interesting finding was the rise of collaborative ePortfolios, which contrasts with the traditional notion of ePortfolios as individual endeavours. The pandemic prompted institutions to encourage collaborative project-based learning, where students used ePortfolios not just to showcase their individual achievements, but also to document group projects, peer feedback, and co-creation of knowledge. Collaborative ePortfolios enabled students to continue learning and working together despite physical separation, fostering peer engagement, communication skills, and a sense of community.

The adoption of collaborative ePortfolios also aligns with the increasing emphasis on 21st-century skills, such as collaboration, critical thinking, and digital literacy, which are essential for students to thrive in the modern workforce. As indicated by Participant 5, working together on ePortfolios facilitated a peer-supported learning environment, where students could challenge each other’s ideas, provide constructive feedback, and improve their collaborative skills. This process mirrors the constructivist learning theory (Piaget, 1970), which emphasizes that knowledge construction is often enhanced through social interaction and collaborative problem-solving.

Challenges in Implementation

Despite the benefits, several challenges emerged in the implementation of ePortfolios during and after the pandemic. The technological barriers faced by students, such as limited access to reliable internet and devices, were highlighted as a significant issue. Some students found it difficult to engage with ePortfolios, particularly those without sufficient technological resources. Lecture 2 commented:

“While ePortfolios were a great tool for assessment and learning, we did see that not all students had access to the same resources. This created a digital divide that was hard to overcome in such a short period. Some students struggled to fully engage with the platform because of connectivity issues or lack of proper devices.”

Student 10 highlighted:

“I agree that ePortfolios were a great tool for assessment and learning, especially for digital projects. We did see that not all students had access to the same resources. Some have network challenges since they were living in remote rural areas where they were supposed to travel long distances to access the network to do any activity or task given.” S10

Additionally, both students and lecturers expressed concerns about the learning curve associated with using ePortfolio platforms. Most lecturers were not adequately trained in how to effectively utilize ePortfolios for assessment purposes, which led to a lack of guidance and inconsistent feedback practices. Student 7 noted:

“I had some challenges at the beginning with the ePortfolio platform. The instructions were unclear, and I wasn’t sure how to integrate all my work in a cohesive way. It took some time to figure out the best way to use it effectively. It seems like most staff members were not trained how to assist students who have challenges. It was trial and error for me.” S7

Technological issues and a lack of sufficient training were significant barriers in the widespread adoption and effective use of ePortfolios during the pandemic era.

While the advantages of ePortfolios are evident, the challenges associated with their widespread adoption during the pandemic must not be overlooked. Technological barriers emerged as a significant issue, particularly for students without access to reliable internet or devices. The digital divide was clearly highlighted in the findings, with some students reporting difficulties in engaging with ePortfolios due to inadequate resources. This observation supports the findings of Selwyn (2016), who emphasized that technology’s potential is not fully realised unless equitable access is provided.

Moreover, the lack of training for both students and instructors hindered the effective use of ePortfolios. As noted by several participants, the learning curve for mastering ePortfolio platforms was steep, and many educators were not well-prepared to integrate ePortfolios into their teaching practices. This finding highlights the need for comprehensive professional development and student support in the adoption of new technologies in education.

As a way to minimise the challenge mentioned, universities can adopt ePortfolio tools that are accessible on low-speed internet and optimized for mobile devices, such as Google Sites, Mahara Lite, and Seesaw for younger students. They can set up dedicated ePortfolio support centres (virtual or on-campus) to troubleshoot access, file uploads, and platform navigation. They can enable offline saving and uploading features. Allow alternative formats such as PDFs or videos shared via USB or cloud links when needed. Institutions can partner with local or national programs to distribute laptops or Wi-Fi hotspots to students who lack adequate technology at home.

The Future of ePortfolios in Post-COVID Education

Looking ahead, participants expressed optimism about the continued use of ePortfolios in post-pandemic education. Many felt that the flexibility, reflection, and self-directed learning promoted by ePortfolios were valuable components that should be integrated into future teaching and assessment strategies. Lecturer 1 shared:

“While the pandemic forced us to use ePortfolios out of necessity, I believe it’s a tool that can continue to enhance learning beyond this crisis. It provides a more holistic approach to assessment and offers students a platform to showcase their growth over time.”

The study indicates that ePortfolios are likely to remain a fixture in higher education, not just as a response to emergencies but as part of a broader shift toward more personalised and student-centred learning.

The results suggest that ePortfolios will continue to play a key role in shaping post-pandemic education by supporting personalised, flexible, and reflective learning experiences. The results of this study demonstrate that ePortfolios played a pivotal role in ensuring educational resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. They provided flexible, reflective, and collaborative learning environments that allowed students to continue their academic work despite the challenges of remote learning. However, challenges related to technology access and platform usability must be addressed to fully realise the potential of ePortfolios in future educational contexts.

Despite these challenges, eight of the 12 study participants expressed strong support for the continued use of ePortfolios in post-pandemic education. Many felt that ePortfolios had demonstrated their educational value and should remain a central component of teaching and assessment strategies moving forward. The shift toward student-centred learning and the demand for more personalised, flexible educational experiences suggest that ePortfolios will continue to thrive in the future.

Furthermore, the potential for collaborative ePortfolios to foster peer learning and engagement is an exciting development, and institutions should consider expanding this approach in their curricula. As the education sector recovers from the pandemic, ePortfolios can play a critical role in creating more adaptive, inclusive, and holistic assessment practices

CONCLUSION

This study underscores the resilience of ePortfolios during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting their flexibility, reflective capabilities, and role in fostering collaborative learning. It also underscores how ePortfolios are being used not just as assessment tools, but as authentic spaces for students to narrate their learning in their own voice, style, and medium. ePortfolios provided a powerful tool for maintaining continuity in teaching and assessment, particularly during periods of disruption caused by the pandemic. However, challenges such as technological inequities and the need for sufficient training must be addressed to maximise their impact. Looking forward, ePortfolios are poised to remain a vital tool in education, offering opportunities for self-directed learning, reflection, and collaborative engagement. As the educational landscape continues to evolve, institutions must leverage ePortfolios to support diverse learning experiences, preparing students for the increasingly digital and interconnected world. For ePortfolios to reach their full potential, institutions must invest in training, technological support, and inclusive practices that ensure all students can benefit from these transformative tools. Only then can ePortfolios continue to contribute to more personalised, flexible, and equitable learning experiences in higher education.

REFERENCES

Abuzaid, A., Miyoshi, T., Mudau, L., Modise, M., Rodríguez, R., & Tucker, G. (2022). A Systematic Review of e‑Portfolio Use During the Pandemic: Inspiration for Post‑COVID‑19 Practices. Open Praxis, 16(3), 656–672.

Barrett, H. (2007). Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: The REFLECT Initiative. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(6), 436–449.

Barrett, H. (2010). Balancing the two faces of ePortfolios. Educação, Formação & Tecnologias, 3(1), 6–14.

Batson, T. (2010). The ePortfolio as a genre of learning. Peer Review, 12(1), 4–8.

Batson, T. (2011). The ePortfolio hijack: Why ePortfolios have not taken hold and what we can do about it. Campus Technology.

Bennett, D., Rowley, J., Dunbar-Hall, P., Hitchcock, M., & Blom, D. (2012). Electronic portfolios and learner identity: An ePortfolio case study in music and writing. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 36(1), 1–12.

Blair, K. L. (2013). Rhetorical practices of digital citizenship: Digital composing and the ethical self. Computers and Composition, 30(3), 144–153.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Buyarski, C. A., & Landis, C. M. (2014). Using an ePortfolio to assess the outcomes of a first-year seminar: Student narrative and authentic assessment. International Journal of ePortfolio, 4(1), 49–60.

Buzzetto-More, N. A. (2010). Assessing the efficacy and effectiveness of an ePortfolio used for summative assessment. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, 6, 61–85.

Cambridge, D. (2010). Eportfolios for lifelong learning and assessment. Jossey-Bass.

Chen, H. (2010). Documenting learning with ePortfolios: A guide for college instructors. Wiley.

Chen, H. L., Penny Light, T., & Watson, C. E. (2021). Electronic portfolios and student success: Effectiveness, efficiency, and learning. Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Eynon, B., Gambino, L. M., & Török, J. (2014). Catalyst for Learning: ePortfolio research and practice. https://c2l.mcnrc.org

Eynon, B., & Gambino, L. M. (2017). High-impact ePortfolio practice: A catalyst for student, faculty, and institutional learning. Stylus Publishing.

Garrett, B. M., & Jackson, C. (2006). A mobile clinical e‐portfolio for nursing and medical students, using wireless personal digital assistants (PDAs). Nurse Education Today, 26(8), 647–654.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7–23.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000a). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. (Foundation of the Community of Inquiry model).

Gwizangwe, I., Mhishi, M., Zezekwa, N., Mpofu, V., Sunzuma, G., Mudzamiri, E., Manyeredzi, T. Munakandafa, Chagwiza, C. J., Ndemo, Z., Kazunga, C., Mutambara, L. N. H. (2019). E-Teaching Practice Model Administration Manual, Bindura University of Science Education, Bindura.

Hallam, G., & Creagh, T. (2010a). ePortfolio use by university students in Australia: A review of the Australian ePortfolio Project. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(2), 179–193.

Hallam, G., & Creagh, T. (2010). ePortfolios: Research and practice in higher education. Australian Flexible Learning Framework.

JISC. (2020). The future of assessment: Five principles, five targets for 2025. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/

LaMagna, M. (2017). Faculty and student perceptions of the implementation of electronic portfolios in nursing education. Nurse Educator, 42(3), 127–131.

Lorenzo, G., & Ittelson, J. (2005). An overview of ePortfolios. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative Paper 1.

López-Pastor, V. M., Sicilia-Camacho, A., & Pérez-Pueyo, Á. (2020). Formative and shared assessment in higher education through ePortfolios during COVID-19. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 20(6), 3306–3314.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

Modise, M. P., & Mudau, P. K. (2022). Using ePortfolios for Meaningful Teaching and Learning in Distance Education in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2022.2067731

Nguyen, T., & Habók, A. (2021). Digital transformation in higher education assessment during COVID-19: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 26, 7245–7279.

Nguyen, L., & Ikeda, M. (2021). Eportfolio as a transformative tool for higher education: A systematic review. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6498

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Piaget, J. (1970). Science of education and the psychology of the child. Orion Press.

Reese, M., & Levy, R. (2009). Assessing the future: ePortfolio trends, uses, and options in higher education. EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research Bulletin, 2009(4), 1–12.

Rowley, J., & Munday, J. (2018). A ‘building block’ approach to ePortfolios: A case study of how an ePortfolio can support professional learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 34(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4116

Slade, C., Murfin, K., & Readman, K. (2019). Evaluating the ethics of ePortfolios: A literature review. International Journal of ePortfolio, 9(1), 1–10.

Stefani, L., Mason, R., & Pegler, C. (2007). The educational potential of ePortfolios: Supporting personal development and reflective learning. Routledge.

Thanos, K., & Nagelhout, E. (Eds.). (2023). ePortfolios@EDU: What we know, what we don’t know, and everything in between. The WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/practice/portfolios/

Torres-Hernández, N., & Gil-Fernández, R. (2021). Eportfolio as an assessment tool in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 22, e25408. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.25408

Trust, T., & Whalen, J. (2020). Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 189–199.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Watson, C. E., Kuh, G. D., Rhodes, T. L., Light, T. P., & Chen, H. L. (2016). ePortfolios—The eleventh High-Impact Practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 6(2), 65–69.

Yancey, K. B. (2009). Electronic portfolios a decade into the 21st century: What we know, what we need to know. Peer Review, 11(1), 28–32.

Yancey, K. B. (2019). ePortfolios and the problem of transfer: Insights from a five-year study. In ePortfolio as curriculum: Models and practices for developing students’ ePortfolio literacy (pp. 55–69). Stylus Publishing.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2023). Collaborative e‑portfolios use in higher education during the COVID‑19 pandemic: A co‑design strategy. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 9(3), 585–601.

Zhou, W., & Brown, D. (2015). Educational learning theories: 2.0 implications for online learning. Journal of Education and Learning, 4(3), 31–42.

APPENDIX: SAMPLE INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

For Students (Final-Year Diploma in Science Education)

1.ePortfolio Experience & Purpose

Can you describe the purpose of the ePortfolio in your teaching practice? What types of artifacts (lesson plans, multimedia, reflections) did you include?

2. Design & Structure

How was the ePortfolio structured or organized? Did it follow a specific template or module outline?

3. Reflective Value

In what ways did completing the ePortfolio help you reflect on your teaching practice or learning journey?

4. Ease of Use & Accessibility

How easy or difficult was it to use the ePortfolio platform? What features helped or hindered your experience?

5. Support & Guidance

What kind of support (e.g., rubrics, technical help, feedback) did you receive when creating your ePortfolio?

6. Challenges Encountered

What challenges did you face in putting together your ePortfolio—technological, time-related, or otherwise?

7. Peer Interaction & Feedback

Did you share your ePortfolio with classmates or receive peer feedback? How did that impact your learning?

8. Benefits Perceived

What do you believe were the main benefits of using an ePortfolio during your teaching practice?

9. COVID-19 Context

How did the shift to remote or blended teaching during the pandemic affect your use of the ePortfolio?

10. Suggestions for Improvement

What would you change or improve about the ePortfolio process or platform?

For Lecturers (Supervising Educators)

1. Purpose & Integration

What was the institutional purpose behind integrating ePortfolios into your students’ teaching practice?

2. Instructional Design & Support

How did you prepare your students for ePortfolio use? What resources or training were provided?

3. Usability & Platform Selection

How user-friendly was the ePortfolio platform for both you and the students? What were its strengths and weaknesses?”

4. Feedback Practices

How did you use the ePortfolio to give feedback? Were rubrics or structured prompts part of the process?

5. Student Engagement & Reflection

In what ways did the ePortfolio enhance student reflection and engagement in their teaching practice?

6. Observed Challenges

What challenges or barriers did you observe, such as technical issues or uneven digital literacy?

7. Adaptation During COVID-19

How did your approach to using ePortfolios change with the onset of the pandemic?

8. Institutional Alignment

To what extent did institutional policies or module outlines support or shape the use of ePortfolios?

9. Professional Benefits

What benefits, if any, did you observe among students in using ePortfolios—such as deeper reflection or better documentation?

10. Recommendations

What improvements or changes would you recommend for future use of ePortfolios in your context?

AUTHORS

Dr. Cathrine Kazunga is a Mathematics Education expert with a strong academic background and professional experience. She holds a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Mathematics Education from the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, a Master of Education in Science (Mathematics), and a Bachelor of Education in Mathematics (HBScEd) from Bindura University of Science Education. She has vast experience in teaching and training teachers and experience in primary, secondary, and tertiary mathematics. Her research interests are the teaching and learning of linear algebra, STEM education, ICT integration into mathematics teaching and curriculum interpretation, and classroom mathematics. She has the following awards from Bindura University of Science Education: best student and Vice Chancellor award (2008) and Organisation of Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD) Postgraduate Training Fellowships for Women Scientists in Sub-Saharan Africa and Least Developed Countries (2013). She had several publications and presented her work to different conferences nationally, regionally, and internationally.

Email: kathytembo@gmail.com

Dr. Lytion Chiromo is a Dean of Students at Reformed Church University. He holds a Ph.D. in Restorative Justice from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, a Master of Arts, a Bachelor of Arts Special Honours, a Bachelor of Arts General, a Diploma in Adult and Continuing Education, and a Diploma in Education. He possesses a strong administrative and academic background. He has vast experience in the teaching of mathematics at the primary and tertiary levels. He also has vast experience in teaching and training teachers, with experience in primary, secondary, and tertiary education. With a strong research focus, he authored articles and published papers in reputable journals. His expertise spans areas in the teaching and learning of STEM education. As a dedicated educator, he inspires students with their passion for mathematics, fostering a love for learning and academic excellence.

Email: mahunzuhunzul@gmail.com