43 The Promise of ePortfolios for Student Agency in Distance Education and Higher Education: A Systematic Review

Mpho-Entle Puleng Modise

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

This chapter explores the educational value and role of electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) in promoting student agency, particularly in distance education (DE) and higher education (HE) contexts. Research reports the increased adoption of e-portfolios as highly flexible and interactive tools, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. ePortfolios are digital spaces facilitating evidence-based teaching and learning by encouraging students to reflect on, document, and present their learning journeys. Recognised as high-impact practice tools, ePortfolios are particularly valuable in DE and HE contexts where students benefit from autonomy, reflection, and continuous feedback. This chapter aims to deepen understanding of e-portfolio practices and their potential to enhance student agency. Drawing on a systematic review of literature published between 2015 and 2025, through rigorous inclusion/exclusion criteria, findings from ten selected peer–reviewed journal articles highlight current trends, benefits, and challenges associated with ePortfolios. The findings emphasise the importance of designing learning environments that support autonomy, structured reflection, engagement and supporting teacher and student agency through e-portfolio pedagogy. Recommended future research directions include longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impact of e-portfolios on student agency and investigations into integrating e-portfolio pedagogy in various educational contexts.

Keywords: e-assessment, ePortfolios, digital learning, higher education, reflective practice tools, student agency, systematic review, technology adoption

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, ePortfolios have emerged as transformative tools in higher education, particularly within distance education contexts. The rise in adoption of ePortfolio was reported during the COVID-19 pandemic, proving them to be flexible and digitally resilient pedagogical tools. The shift towards online and blended learning modalities, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has further highlighted the relevance of e-portfolios in facilitating meaningful educational experiences for students (Mudau & Modise, 2022). ePortfolios offer platforms for students to document learning, reflect on experiences, and showcase competencies, fostering self-directed learning and enhancing student agency (McLellan, 2021).

Empirical studies have highlighted the multifaceted benefits of ePortfolio integration. For example, ePortfolios have been shown to enhance students’ self-directed learning skills, including goal setting, task analysis, and self-evaluation (Beckers, Dolmans & Van Merriënboer, 2016; Jimoyiannis & Tsiotakis, 2016), when effectively integrated into educational routines with appropriate scaffolding and faculty support. In distance education settings, particularly in developing countries, e-portfolios have been instrumental in promoting critical thinking, lifelong learning, and meaningful feedback, despite challenges related to technological infrastructure and user familiarity (Modise & Mudau, 2022; Van Wyk, 2017).

E-portfolios serve multiple functions: showcase, learning, assessment, and professional development. They include digital artefacts such as written assignments, multimedia content, peer feedback, and reflective journals. Corley and Zubizarreta (2012) noted that e-portfolios are both a product and a process, reflecting students’ ability to organise, analyse, and communicate their work. According to Corley & Zubizarreta (2012), a good ePortfolio is both a product of a digital collection of artefacts and a process of reflecting on those artefacts and what they represent, also on organising, prioritising, analysing, and communicating one‘s work and its value.

This chapter systematically reviewed and synthesised current research on the role of ePortfolios in enhancing student agency within distance and higher education contexts. Developing robust approaches for teaching and assessing student agency is essential to help students thrive in today’s world (Brandt, 2025). The chapter provides insights for educators and institutions that leverage these tools for improved educational outcomes.

Student agency

Student agency has been an object of academic interest for decades (Klemenčič, 2015; Stenalt & Lassesen, 2022; Inouye, Lee& Oldac, 2023). The concept of student agency is rooted in the principle that students have the ability and the will to influence their own lives and the world around them positively (OECD, 2018; Zhang & Tur, 2023, Zhang & Tur, 2025; Vincent & Hynes, 2016). Agency can be exercised in every context: moral, social, economic, and creative. In their study, Ivey and Johnston (2013) identified specific dimensions of agency, including five domains: agency in reading, social agency, moral agency, agency with respect to one’s life narrative, and agency in self-regulation. Agency also overlaps with concepts such as autonomy, self-regulation, self-efficacy, motivation and self-directed learning; however, Brandt (2025) argues these remain distinct.

Student agency is closely related to human agency, which is characterised by one’s intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness, which enable a human to ensure an activity occurs (Bandura, 2001). From his social constructivism theory, Bandura (1977) identifies four interconnected components essential for human agency: intentionality (i.e. setting goals and planning purposeful actions), forethought (i.e. anticipating future events and adjusting accordingly), self-regulation (i.e. managing emotions and behaviours to achieve goals) and self-reflectiveness (i.e. evaluating one’s actions and effectiveness) (Brandt, 2025). Human agency is also related to constructs such as control (Malone & Lepper, 1987), self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2000), and self-regulated learning (Winne, 2018; Brandt, 2025).

OECD (2018) thus defines student agency as “the capacity to set a goal, reflect and act responsibly to effect change”. Closely, Brandt (2025) defines student agency as “the ability to exercise control over one’s own thought processes, motivation and action” (p.9). Bandura (1989, 2001) explained that agency is associated with an individual’s self-efficacy and striving to control their learning activities.

Stenalt and Lassesen (2022, p. 653) found that a student agency perspective “is integrated into research focused on assessment and feedback, globalisation and internationalisation, knowledge production, learning analytics, learning connections and transfer, real-life learning situations, and student-focussed teaching and learning”.

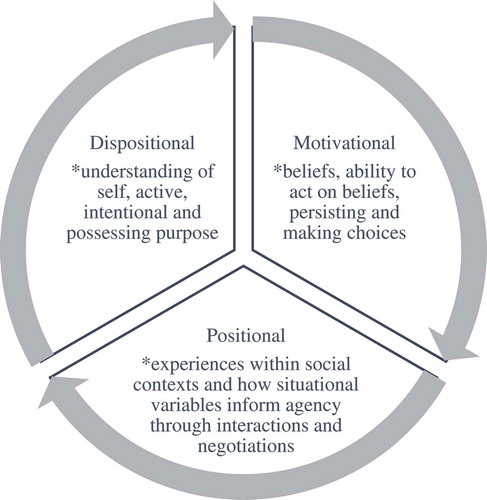

Vaughn (2020) developed a model of agency in learning contexts with dispositional, motivational, and positional dimensions to facilitate critical thinking on student agency within recent educational reforms. Figure 1 outlines the interplay of the agency dimensions.

Figure 1

Model of agency in learning contexts

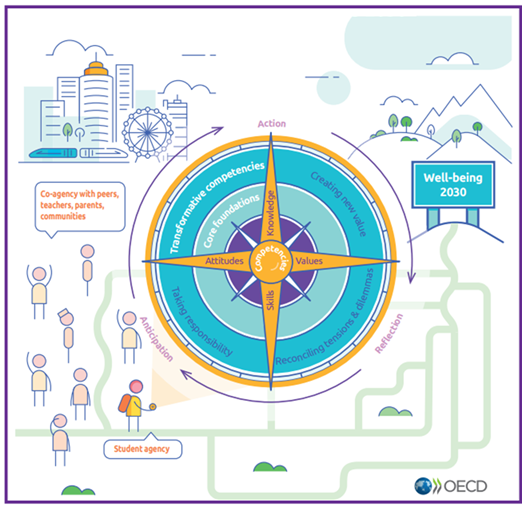

According to OECD (2018), when students are agents in their learning, playing an active role and deciding what and how they will learn, they generally show greater motivation to learn and define objectives for their learning. Figure 2 shows the OECD Learning Compass 2030 framework’s multidimensional nature of educational agency. Accordingly, the OECD Learning Compass 2030 (OECD, 2018, p. 2) include four key points, namely:

- Agency implies the ability and the will to positively influence one’s life and the world around them.

- Students need to build foundation skills to exercise agency to their full potential.

- The concept of student agency varies across cultures and develops over a lifetime.

- Co-agency is defined as interactive, mutually supportive relationships–with parents, teachers, the community, and each other– that help students progress towards their shared goals.

Research shows that self-directed learners are self-regulated and highly motivated individuals who act independently and take responsibility for their actions (Beckers, Dolmans & Van Merriënboer, 2016; Brandt & Buckley, 2020), with the ability to choose aspects of their learning, which ushers deeper learning. Brandt and Buckley (2020) further argue that 21st Century learning represents skills such as problem solving, collaboration, self-direction, creativity, critical thinking, and complex communication that can be universally applied to enhance ways of learning, working and living.

Figure 2

OECD Learning Compass 2030

This chapter highlights the aspects of educational agency that are relevant and evident in e-portfolio use in higher education and distance education. These are reported extensively in research; thus, the following section presents the dynamic educational technology tool making waves in higher and distance education environments, e-portfolios.

Electronic portfolios in higher education and distance education

Electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) have become a popular pedagogical approach in various professional and educational disciplines within higher education and distance education (Green, Wyllie & Jackson, 2014; Lu, 2021; Modise, 2021). Rahayua et al. (2016, p. 1) define a portfolio as “a document describing skills, experience, interest or knowledge of a person”, and argue that portfolios can no longer keep pace with times, and that e-portfolios can overcome this weakness. Therefore, the static nature of the portfolio promoted e-portfolios as a dynamic educational tool that is digitally resilient and can keep up with the constant technological changes. This promotion highlighted the digital resilience of e-portfolio during COVID-19, as pedagogical tools that promoted continuity during the disruptive pandemic. Also, it is highly effective in maintaining student engagement (Mudau & Modise, 2022).

Many definitions of an ePortfolio exist in the literature (Rezgui, Mhiri & Ghédira, 2018). For example, Abrami and Barrett (2005) define ePortfolio as an instrument to capture, compare and develop the skills and competencies of human resources and lifelong learning, by gathering qualitative data from digital professional profiles of individuals. Balaban, Divjak, and Mu (2011) define it as a digital record containing evidence of achievement and self-evaluation that can be shared on a limited basis to support the learning process of formal, informal and non-formal.

The definitions are clearly evolving, from a mere collection of artefacts to including reflection and multimedia. However, most definitions look at the individualised approach of e-portfolio, not including the collaborative nature of ePortfolios. This chapter adopts the following definition by Modise (2023, p. 4): “an e-portfolio is a digital teaching and learning space that supports reflective, personalised, and collaborative learning”. Modise (2023) argues that this virtual environment allows the purposeful presentation and reflection on evidence of learning through various multimedia artefacts linked to the learning outcomes.

An e-portfolio is a dynamic digital learning space where learners co-create and share knowledge; assess each other’s work, reflect, and help each other. It is a space where they interact with content, technology, other learners and instructors. This is more than collecting and showcasing marked assignments/artefacts and storing them on whatever platform they use. An e-portfolio is about a community. Various stakeholders form part of students’ learning environment, which promotes co-agency in ePortfolios. According to OECD (2018), “co-agency implies relationships with others: parents, peers, teachers and the community” (p.7), each playing a key role in a learning environment that promotes the development of a student’s identity and a sense of belonging.

Mudau and Modise (2022, p. 434) advocated for a clear institutional definition and a shared understanding of ePortfolio within the university and in similar contexts. Consequently, they suggested a definition of an e-portfolio within the ODL and e-learning environment: “an e-portfolio is a purposeful development and compilation of academic work that is presented as evidence of a student’s academic achievement and learning journey through various digital artifacts in an online or web-based system.”

However, Modise’s (2023) definition and approach highlight the personalised and collaborative nature of ePortfolios, the interaction between content, teacher, students and technology. The definition highlights the presences outlined by Garrison, Anderson, and Archer‘s (2000) Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework. The definition also acknowledges the mediating role of technology in distance education, addressing Moore’s transactional distance – ‘the psychological and communicative space’ between the teacher and learner (1980), which assumes that strategies and services are put in place to support students adequately. Relevant assessment tools are employed to assess the learning that has happened appropriately.

Therefore, understanding the foundation of ePortfolios is important in understanding its role for education in the digital 21st Century. The use of digital portfolios has been associated with increased student autonomy and digital competence. Studies indicate that students engaging with ePortfolios develop greater self-awareness of their learning strategies and exhibit improved self-regulation and reflective capacities (Vincent & Hynes, 2016).

Benefits of ePortfolios

Among other recorded benefits of e-portfolios (Lam, 2023; Banks, 2004; Ciesielkiewicz, 2019; Walland & Shaw, 2022) is assessment, which enables students to integrate their learning and make connections between subjects in an authentic and meaningful way (Buente et. al., 2015; Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Morreale et. al. 2017) self-regulated learning, development of critical thinking skills, and active engagement, reflection (Nguyen, 2015; Farrell, 2018; Farrell & Seery; 2018; Modise & Mudau, 2022).

Research also shows that learning with an e-portfolio can foster a sense of belonging to a community and collaboration with peers (Barbera, 2009; Bolliger & Shepherd, 2010) and promote innovative life-long learning (Kwok & Hui, 2018). Marinho, Fernandes and Pimentel (2021) further argue that e-portfolios also serve as effective assessment strategies, mediating learning processes and fostering collaboration in blended learning environments.

Despite these promising outcomes, the implementation of e-portfolios is not without challenges. Issues such as technical difficulties, lack of guidance, and concerns over privacy and plagiarism have been identified as barriers to effective adoption. Furthermore, the impact of e-portfolios on student well-being and engagement requires careful consideration, as their design and integration into curricula can influence students’ motivation and perception of value (Zhang & Tur, 2024a, 2024b; McCarthy, Mitchell & McNally, 2024). Overall, the records of benefits of e-portfolios far surpass the recorded challenges.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This chapter explored the educational value of e-portfolios in promoting student agency, particularly in distance education and higher education contexts. Using a narrative systematic review (Felix, 2024; Siddaway et al., 2019), the research followed a qualitative approach. The research question guiding the research was “How do ePortfolios support the development of student agency in distance and higher education contexts?”

Following ethical research procedures and guided by the 2020 PRISMA framework (Page et al. 2021), the review targeted peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between 2015 and 2025. The main inclusion criteria (Table 1) focused on studies that addressed the educational use and impact of e-portfolios, excluding articles that focused solely on assessment through e-portfolios. The private institutions were purposively excluded as they often have adequate technology resources to adopt e-portfolios and other online learning related approaches, whereas public educational institutions (Chomunorwa & Mugobo, 2023).

Table 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (created by Author)

|

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

|

Published 2015 – 2025 |

Published before 2015 or after March 2025 |

|

English language only |

Not in English |

|

Distance education / Higher education |

Not Basic Education (primary and secondary/middle school education) Not Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Not Community Education and Training (CET) |

|

Public institutions |

Not private education |

|

Peer-reviewed journal articles |

Books, Book chapters, conference proceedings, grey literature, dissertations, and theses, |

|

Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar |

Not other databases |

|

e-portfolios |

traditional paper-based portfolio |

The PICOTS framework (Boland, Cherry & Dickson, 2017) was used to identify the key search terms applied across Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Due to the limitation of resources, only these three databases were selected. The search string used across the databases was: e-portfolios OR (electronic portfolios) AND (student agency OR learner agency) AND (higher education OR distance education).

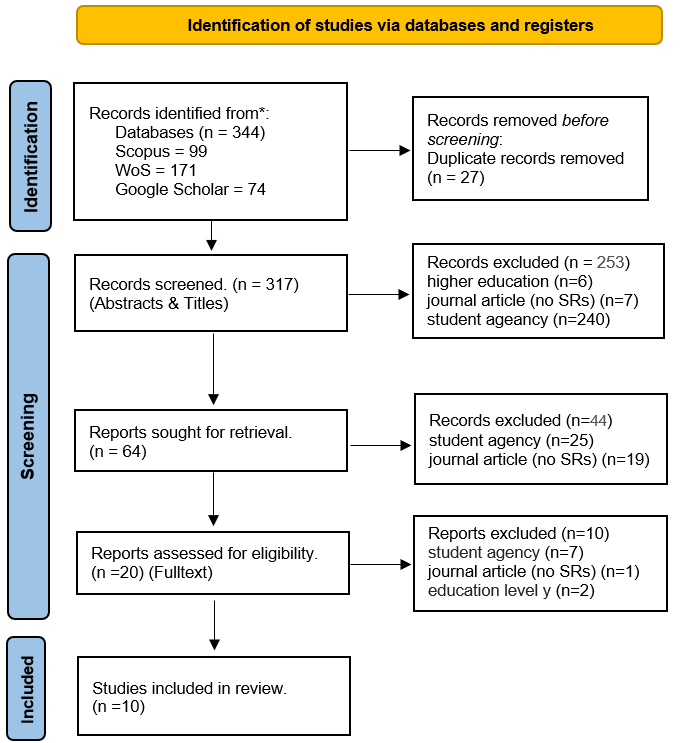

The sources (344) were uploaded to Rayyan, an artificial intelligence (AI) powered application designed to streamline the systematic review process (Rayyan Systems Inc., n.d.) for screening and organising the review process, and Zotero for managing the references. After this systematic screening process, ten items were included for data extraction. Due to the lack of funding, the free version of Rayyan was used. Therefore, only the screening was done in Rayyan, and data extraction and analysis were done manually. The screening process is presented in the following PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021) in Figure 3.

Most items were excluded based on their relevance to student agency, and some were not primary research. Although some of these studies emphasised learner agency, self-directed learning and self-efficacy, or other constructs related to student agency, most followed a literature review approach, disqualifying them for inclusion in this research.

Figure 3

PRISMA flow diagram (created by Author)

The ten items that were selected are also listed in Table 2 below.

Tabel 2

Included items (n=10) (created by Author)

|

Item |

Authors, Year of Publication |

Title of study |

|

1 |

Beckers, Dolmans & van Merriënboer (2022) |

Student, direct thyself! Facilitating self-directed learning skills and motivation with an electronic development portfolio. |

|

2 |

Bennett, Rowley, Dunbar-Hall, Hitchcock & Blom (2016) |

Electronic portfolios and learner identity: An e-portfolio case study in music and writing |

|

3 |

Gámiz-Sánchez, Gallego-Arrufat & Crisol-Moya (2016) |

Impact of electronic portfolios on prospective teachers’ participation, motivation, and autonomous learning. |

|

4 |

Kusum & Waluyo (2023) |

Enacting e-portfolios in online English-speaking courses: Speaking performance and self-efficacy, |

|

5 |

Mogas, Cea Álvarez & Pazos-Justo (2023) |

The Contribution of Digital Portfolios to Higher Education Students’ Autonomy and Digital Competence. Education Sciences, |

|

6 |

Mudau & Modise (2022) |

Using E-Portfolios For Active Student Engagement In The ODEL Environment. |

|

7 |

Sultana, Lim & Liang (2020) |

E-portfolios and the development of students’ reflective thinking at a Hong Kong University. |

|

8 |

van Wyk (2018) |

E-portfolio as an empowering tool in the teaching methodology of economics at an open distance e-learning university. |

|

9 |

Yang, Tai & Lim (2016) |

The role of e-portfolios in supporting productive learning. |

|

10 |

Younghusband (2021) |

E-portfolios and exploring one’s identity in teacher education |

Limitations

Torres Castro and Pineda-Báez (2023) argue that although Scopus is a highly valued academic database, it may not include all relevant documents produced in specific fields, as WoS and Google Scholar. This study focused only on peer-reviewed journal articles, excluding other sources. Other sources not included in this study may include research on e-portfolios that address student agency.

The study also only focused on research published between 2015 and 2025. However, the items included in this study, supported by literature, are enough to present the student agency and many educational benefits, as the promise of e-portfolios in higher education and distance education. The following section presents the results from the selected peer-reviewed journal articles concerning the research question.

RESULTS

Studies Characteristics

The included studies include solo-authored and co-authored works, mostly intra-institutional collaborations (Table 3). This trend is mainly due to case study research designs using participants within these HEIs. The studies also reflect diverse geographical contexts, showcasing research conducted across various countries.

Tabel 3

Overview of Studies by University/Country, Academic Field, Level of Education, and Number of Participants (created by Author)

|

Item |

University, Country |

Academic Field |

Level of Education |

No of Participants |

|

1 |

Netherlands |

Educational Technology, Vocational Education |

Senior vocational education |

54 students (25 PERFLECT group, 29 REGULAR group) |

|

2 |

Sydney |

Arts (Music: performance, creative and professional writing) |

Undergraduate |

220 students (186 music, 34 writing); 5 educators |

|

3 |

University of Granada, Spain |

Education |

Undergraduate (Teacher Education) |

104 undergraduate students |

|

4 |

Public University, Indonesia |

Education, English Language Teaching (ELT) |

Higher Education (University-level EFL students) |

55 university students (28 experimental, 27 control) |

|

5 |

Six universities across Spain, Portugal, Norway, Poland, and France |

Education Sciences, |

Higher Education (Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctoral students) |

355 university students |

|

6 |

University of South Africa |

Education |

Higher Education |

25 university students |

|

7 |

Hong Kong University |

Education |

University |

One teacher and six undergraduate students |

|

8 |

University of South Africa |

Education, Curriculum Studies, Economics |

Postgraduate (PGCE and BEd in Senior Phase and Further Education and Training) |

368 university students |

|

9 |

Hong Kong |

Education, Curriculum Studies |

First-year Undergraduate Students |

6 first-year undergraduate students |

|

10 |

University of Northern British Columbia, Canada |

Teacher Education |

Post-baccalaureate Bachelor of Education (Teacher Education Program) |

Six cohorts, approx. 10–30 students per cohort |

Two studies from Hong Kong (Sultana et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2016), and two from South Africa (Mudau & Modise, 2022; Van Wyk, 2018), and one from the following countries: the Netherlands, Sydney, Indonesia, Canada, and Spain. One study involved six universities across Spain, Portugal, Norway, Poland, and France (Mogas et al., 2023).

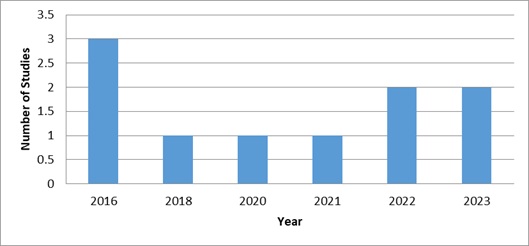

As shown in Table 3, most studies involved student participants in higher education, including vocational education, with a mix of undergraduate and postgraduate studies, ranging from six to 368 participants. All the studies selected were within the education field. The items included in this study were published between 2016 and 2023; the inclusion/exclusion criteria searched for peer-reviewed articles published between January 2015 and March 2025. Three studies were published in 2016, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Number of studies published by year

Overview of studies‘ research designs and theoretical framework

A clear trend across the studies is the dominance of mixed methods research, appearing in nearly half of the designs (Table 4).

Table 4

Overview of Studies by Methodology (created by Author)

Studies’ Research Designs

The studies reviewed demonstrate a rich diversity in research approaches, with a strong emphasis on mixed methods designs (Yang et al., 2016; Kusum & Waluyo, 2023; Gámiz-Sánchez et al., 2016; Beckers et al., 2022). These often combine quantitative tools like surveys, questionnaires, and statistical tests with qualitative techniques such as interviews, reflections, and open-ended responses. For example, several studies used validated instruments like the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire or IELTS-based speaking tests (Beckers, Dolmans & van Merriënboer, 2022), alongside qualitative interviews and self-assessments, to capture performance data and personal experiences.

Analytical methods were equally varied, ranging from descriptive statistics, MANCOVA, and regression analysis to thematic coding and content analysis (Kusum & Waluyo, 2023), showing a commitment to numerical rigour and narrative depth. Tools like SPSS, NVivo, and Voyant (Younghusband, 2021; Gámiz-Sánchez et al., 2016; Bennett et al., 2016) were used to process and visualise data, especially in studies that explored sentiment and reflection. As indicated, one study of Yang et al. (2016) applied action research principles over three years, using observations, social media posts, and reflective notes to evaluate a program’s impact. Integrating multiple data sources and analytical techniques reflects a thoughtful effort to understand educational phenomena from various angles, balancing structure with nuance, and evidence with experience.

Theoretical Frameworks in the selected studies

Seven of the ten studies in the list use Self-Directed Learning (SDL) and/or Self-Regulated Learning (SRL), with only one study explicitly mentioning SDL (Beckers et al., 2022) as its underpinning theoretical framework. Two studies expressly reference SRL (Yang et al., 2016; Younghusband, 2021), and five studies explicitly indicate reflection frameworks/theories. Reflection and experiential learning are central, informed by Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle, Schön’s Reflective Practice, Boud et al.’s reflective learning model, and Kember et al.’s coding scheme (Yang et al., 2016).

The studies draw on a rich combination of theories and frameworks to explore how e-portfolios support learner agency. Concepts of autonomous learning and self-regulated learning (Gámiz-Sánchez et al., 2016; Mogas et al., 2023; Sultana et al., 2020), grounded in Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (Kusum & Waluyo, 2023), highlight the importance of confidence, goal setting, and persistence. At the core are Sociocognitive Learning theory, SDL and second-order scaffolding (Beckers et al., 2022), emphasising learners’ active role in directing their learning and gradually taking control with structured support.

Possible Selves theory (Bennett et al., 2016) links learners’ identity and future goals to their motivation and agency. The framework connects identity formation with students’ ability to envision and pursue their future selves. Drawing on the Possible Selves theory (Markus & Nurius, 1986), the e-portfolio served as a reflective and developmental tool for constructing and negotiating professional identity, which is closely linked to learner agency and career trajectories.

The study by Yang et al. (2016) framed assessment in e-portfolios as a learning tool, encouraging ongoing self-evaluation and growth. Community of Inquiry framework (Mudau & Modise, 2022), Siemens’ Connectivity Theory and Social Cognitive Theory (van Wyk, 2018) emphasise online collaboration, social interaction, and network learning. Transformative Learning Theory (van Wyk, 2018) highlights the development of metacognition and personal values, while the Learner Agency Framework and Co-PIRS model (Younghusband, 2021) provide practical planning guidance, reflecting, and showcasing learning through e-portfolios. Together, these frameworks illustrate how e-portfolios can promote autonomy, self-regulation, reflection, digital competence, and ultimately, student agency.

Relevance of the selected studies to student agency

Across diverse studies selected in this research, ePortfolios consistently emerge as powerful tools for fostering student agency in higher education. Scholars such as Beckers et al. 2022) and Bennett et al. (2016) emphasise how ePortfolios promote autonomy, self-assessment, and goal-setting, enabling learners to take ownership of their educational journeys. This stance is echoed by Gámiz-Sánchez et al. (2016) and Mudau and Modise (2022), who highlight the role of ePortfolios in encouraging active participation, collaboration, and reflective practice as core components of agency.

In online learning contexts, Kusum and Waluyo (2023) demonstrate how ePortfolios enhance self-efficacy and peer-supported reflection, particularly in language learning. Similarly, Mogas, Cea Álvarez, and Pazos-Justo (2023) draw on self-regulated learning and digital competence frameworks to show how structured ePortfolio use supports agency through intentional learning design. Using the Community of Inquiry framework, Mudau and Modise (2022) illustrate how ePortfolios create interactive, student-centred spaces that nurture engagement and ownership. CoI emphasises cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence. Within e-portfolios, this framework supported active student engagement and ownership of learning (agency) by providing a collaborative, reflective, and interactive learning space (Mudau & Modise, 2022).

Sultana, Lim, and Liang (2020) further reinforce the value of structured reflection and feedback in cultivating autonomy and self-regulation. Van Wyk (2018) and Yang, Tai, and Lim (2016) highlight the role of ePortfolios in identity formation, professional growth, and self-directed learning, particularly among teacher candidates. Bennett, Rowley, Dunbar-Hall, Hitchcock and Blom (2016) argue that the Possible Selves framework supports student agency by promoting autonomy, self-assessment, and goal setting.

E-portfolios are tools for second-order scaffolding, helping students reflect, assess, and plan their learning. Finally, Younghusband (2021) introduces the Co-PIRS model, which explicitly links collaborative decision-making and reflective learning to the development of student agency. These studies affirm that ePortfolios are not merely digital repositories, but dynamic pedagogical tools that empower learners to become active, reflective, and self-directed participants in their education.

DISCUSSION

E-portfolios were initially seen as assessment tools (Marinho et al., 2021) but have since been recognised for their educational value. Accordingly, the findings in this study show that e-portfolios can make assessment more meaningful and authentic, encourage students to participate actively, and support their growth as reflective, independent learners and professionals.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many HEUs to move to online delivery of education functions and services. Mudau and Modise (2022) argue that there was no time for instructors to acquire the necessary skills for designing learning materials for online teaching and learning. However, those teaching with e-portfolios reported the smooth transition to online teaching and learning during the pandemic, proving the flexibility and resilience of e-portfolios as digital pedagogical tools in various contexts. This argument is further supported by research which shows that e-portfolios remain among the most effective, dynamic and flexible tools for teaching, learning, and supporting learners in various educational contexts (Modise, Majola & Kotoka, 2025). The evidence shows that ePortfolios are transformative tools that prepare students to succeed in education and thrive as lifelong learners.

The studies reviewed collectively affirm the transformative potential of ePortfolios in fostering student agency across diverse higher education contexts. They are not just digital folders for storing work, but living tools that help students reflect, grow, and take charge of their learning. ePortfolios are dynamic pedagogical instruments that promote reflection (Younghusband, 2021), autonomy, identity formation, and self-regulated learning (Beckers et al., 2022; Gámiz-Sánchez et al., 2016; Kusuma & Waluyo, 2023). Through ePortfolios, learners build confidence, strengthen their identity, and develop the skills to navigate their academic and professional futures. Their adaptability makes them especially valuable: across countries, disciplines, and learning contexts, ePortfolios consistently create spaces for collaboration, critical engagement, and personal development.

From the studies reviewed, results show that e-portfolios encourage deeper learning (Mudau & Modise, 2022), promote reflective learning (Younghusband, 2021), facilitate self-assessment and goal setting (Kusuma & Waluyo, 2023; Beckers et al., 2022; Bennett et al., 2016), empower students to take ownership of their learning journeys, and support self-directed learning and lifelong learning. These and other skills afforded by these pedagogical tools promote student agency (OECD, 2018; Brandt, 2025).

By drawing on diverse theoretical frameworks, ranging from Self-Directed Learning, Sociocognitive Learning Theory and Possible Selves to experiential and reflective practice, the studies demonstrate how ePortfolios empower learners to take ownership of their educational journeys while fostering collaboration, digital competence, and resilience. The evidence across varied contexts and disciplines highlights the consistent emphasis on learner-centred practices, affirming the relevance and adaptability of ePortfolios in enabling students to engage critically with their learning, envision their futures, and build the confidence and skills necessary for lifelong growth.

Despite their benefits, e-portfolios face challenges such as adoption issues, digital accessibility and equity, data privacy concerns, and the time-consuming nature of setup. Developing countries may also struggle with the necessary infrastructure. E-portfolios are not merely technological tools; they represent personalised, human-centred and culturally sensitive learning journeys. They are also highly interactive tools of reflective teaching and learning. Their successful integration requires careful planning, inclusive practices, and digital literacy. When implemented effectively, they empower learners and educators, fostering deeper engagement and reflective practice.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that e-portfolios hold great promise as teaching and learning tools in higher education and open and distance e-learning (ODeL). Student agency is the much-needed 21st-century skill for higher education students, especially in distance education. Distance learners often experience reduced interaction, lower belonging, and less formative feedback. E-portfolios have shown prominence in fostering agency through structured reflection, visible progress, and ownership of learning among students in various educational contexts.

Student agency, capacities and dispositions that enable learners to act intentionally in their learning (autonomy, voice, choice, self-regulation, goal setting, metacognition, identity formation and authorship) are much needed in distance and higher education contexts where learners are often physically separated from instructors and peers. ePortfolios continue to compensate by providing continuity of identity, scaffolding reflection, and enabling communication and assessment at scale. This study contributes to the body of knowledge by showing the value of e-portfolios in these educational contexts and promoting student agency. The study also highlights the relevance of e-portfolios for high-impact teaching and learning experiences in the digitally educational era. Future research directions may include longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impact of e-portfolios on student agency in various educational contexts.

REFERENCES

Abrami, P., & Barrett, H. (2005). Directions for research and development on electronic portfolios. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 31(3).

Balaban, I., Divjak, B., & Mu, E. (2011). Meta-model of ePortfolio usage in different environments. Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Learning, 35–41.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Banks, B. (2004). e-Portfolios: their use and benefits. A White Paper. FD Learning Ltd. Tribal Technology, 1-13. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/51885295/eportfolios_their_use_and_benefits-libre.pdf?

Barrett, H., & Wilkerson, J. (2004). Conflicting paradigms in electronic portfolio approaches. American Journal of Educational Research, 5(2), 114-123

Beckers, J., Dolmans, D., & Van Merriënboer, J. (2016). e-Portfolios enhancing students’ self-directed learning: A systematic review of influencing factors. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2528

Boland, A., Cherry, G., & Dickson, R. (2017). Doing a systematic review: A student‘s guide (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Brandt, C. (January 29, 2025). Teaching & Assessing 21st Century Skills: A Focus on Student Agency. https://www.nciea.org/blog/student-agency-and-assessment/

Brandt, C., & Buckley, K. (Nov 18, 2020). Making the Case for Social and Emotional Learning Assessment. https://www.nciea.org/blog/the-center-is-getting-emotional-about-assessment/

Chomunorwa, S., & Mugobo, V. V. (2023). Challenges of e-Learning Adoption in South African Public Schools: Learners’ Perspectives. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 10(1), 80-85. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1381091

Ciesielkiewicz, M. (2019). The use of e-portfolios in higher education: From the students’ perspective. Issues in Educational Research, 29(3), 649–667. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.641203511753765

Farrell, O., & Seery, A. (2019). “I am not simply learning and regurgitating information, I am also learning about myself”: Learning portfolio practice and online distance students. Distance Education, 40(1), 76-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1553565

Felix, D. (Nov 6, 2024). Narrative vs. Systematic Literature Review: Understanding the Differences. Sourcely. https://www.sourcely.net/post/narrative-vs-systematic-literature-review

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Green, J., Wyllie, A., & Jackson, D. (2014). Electronic portfolios in nursing education: A review of the literature. Nurse Education in Practice, 14(1), 4-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.011

Inouye, K., Lee, S., & Oldac, Y. I. (2023). A systematic review of student agency in international higher education. Higher Education, 86(4), 891-911.

Ivey, G., & Johnston, P. H. (2013). Engagement with young adult literature: Outcomes and processes. Reading Research Quarterly, 48, 255–275.

Jimoyiannis, A., & Tsiotakis, P. (2016). Self-directed learning in e-portfolios: Analysing students’ performance and learning presence. EAI Endorsed Transactions on E-Learning, 3(9).

Klemenčič, M. (2015). What is student agency? An ontological exploration in the context of research on student engagement. In M. Klemenčič & S. Bergan (Eds.), Student engagement in Europe: Society, higher education and student governance (Council of Europe Higher Education Series No. 20, Vol. 20, pp. 11-29). Council of Europe.

Lam, R. (2023). E-Portfolios: What we know, what we don’t, and what we need to know. RELC Journal, 54(1), 208-215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220974102

Lu, H. (2021). Electronic portfolios in higher education: A review of the literature. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 2(3), 96-101. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejedu.2021.2.3.119

Marinho, P., Fernandes, P., & Pimentel, F. (2021). The digital portfolio as an assessment strategy for learning in higher education. Distance Education, 42(2), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1911628

McCarthy, A., Mitchell, K., & McNally, C. (2024). ePortfolio practice for student well-being in higher education: A scoping review. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice. http://hdl.handle.net/11201/164653

McLellan, P. N. (2021). Collecting a Revolution: Antiracist ePortfolio Pedagogy and Student Agency That Assesses the University. International Journal of ePortfolio, 11(2), 117-130. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1339426

Modise, M. P. (2021). Postgraduate Students’ Perception of the Use of E-Portfolios as a Teaching Tool to Support Learning in an Open and Distance Education Institution. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 283-297. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.508

Modise, M. P. (2023). Towards the integration of ICT into teaching and learning at the high school level through digital technology tools and e-portfolios (Unpublished manuscript). http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.22831.85926

Modise, M. P., & Mudau, P. K. (2022). Using E-Portfolios for Meaningful Teaching and Learning in Distance Education in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 71(3), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2022.2067731

Moore, M. G. (1980). Independent study. In R. Boyd & J. Apps (Eds.), Redefining the discipline of adult education (pp. 16–31). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mudau, P. K., & Modise, M. M. (2022). Using E-Portfolios for Active Student Engagement in the ODeL Environment. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 21, 425-438. https://doi.org/10.28945/5012

OECD. (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030 – The future we want. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/projects/edu/education-2040/concept-notes/Student_Agency_for_2030_concept_note.pdf

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Rahayu, P., Sensuse, D. I., Purwandari, B., Budi, I., & Zulkarnaim, N. (2016, October). Review on e-Portofolio definition, model, type and system. In 2016 International Conference on Information Technology Systems and Innovation (ICITSI) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

Rayyan Systems Inc. (n.d.). Rayyan: AI-powered systematic review tool. https://www.rayyan.ai

Rezgui, K., Mhiri, H., & Ghédira, K. (2018). Towards a common and semantic representation of e-portfolios. Data technologies and applications, 52(4), 520-538.

Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annual review of psychology, 70(1), 747-770. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Stenalt, M. H., & Lassesen, B. (2022). Does student agency benefit student learning? A systematic review of higher education research. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(5), 653-669. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1967874

Torres Castro, U. E., & Pineda-Báez, C. (2023). How has the conceptualisation of student agency in higher education evolved? Mapping the literature from 2000-2022. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 47(9), 1182-1195. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2023.2231358

Vaughn, M. (2020). What is student agency and why is it needed now more than ever?. Theory Into Practice, 59(2), 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1702393

Vincent, C., & Hynes, S. (2016). The Process of Integrating Student Agency into e-Portfolio Design. Journal of Transformative Learning. https://jotl.uco.edu/index.php/jotl/article/download/164/268

Walland, E., & Shaw, S. (2022). E-portfolios in teaching, learning and assessment: tensions in theory and praxis. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(3), 363-379.

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2023, November). Exploring Students’ Agency in ePortfolio Implementation: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Educational Technology Management (pp. 208-214).

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2024a). A Systematic Review of e-Portfolio Use During the Pandemic: Inspiration for Post-COVID-19 Practices. Open Praxis, 16(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.16.3.656

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2024b). An exploration of agency enactment in e-portfolio learning co-design, Digital Education Review. 45, 190–203.

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2025). Enacting Learning Agency Through ePortfolio Implementation: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of ePortfolio, 15(1), 13-31.

AUTHOR

Mpho-Entle Puleng Modise, PhD. is an Associate Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, College of Education at the University of South Africa. Her research areas include faculty and student support in higher education and distance education, open distance e-learning, academic and professional development, technology adoption, and the use of ePortfolios in teaching and learning. Prof. Modise is a member of the SAERA executive committee, advocating for Early Career Researchers in South Africa and Africa. Her commitment to research excellence has earned her several prestigious awards, including recognition for her PhD thesis from EASA and SAERA in 2022, the Women in Research Emerging Researcher Award in 2023, and the External Recognition for Research Excellence award at UNISA in 2024.

Email: modismp@unisa.ac.za