13 Assessing Student Learning and Development through ePortfolios in Higher Education: A Case Study from Zimbabwe

Zacharia Ndemo, Bindura University of Science Education, Zimbabwe

Cathrine Kazunga, Bindura University of Science Education, Zimbabwe

Lytion Chiromo, Reformed Church University, Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

ePortfolios play a vital role in the assessment and evaluation of students’ work in most universities in Southern Africa. The study aims at exploring the assessment and evaluation methods used for assessing student teachers on teaching practice’s learning and development using the students’ ePortfolios. The chapter used qualitative methods using a case study of a particular public university in Zimbabwe. Data was elicited through content analysis, observations, interviews and focus group discussion with twelve participants who were selected using purposive sampling. The main findings were that the university saved lots of money and time through the assessment and evaluation of students’ learning and development using ePortfolios. The students sent their ePortfolios through the internet to the coordinator, who distributed the ePortfolios to colleagues for examination and marking. Students received timely feedback and guidance through email. However, there were some challenges including internet interruptions. The ePortfolio platforms should include review and confirmation steps before the final submission. This would allow students to double-check their uploads and avoid sending incorrect or incomplete documents. To minimise disruptions caused by unstable internet connections, ePortfolio platforms should support auto-saving and offline access. Students should receive training on how to prepare, organise, and submit ePortfolio content properly. Clear instructions and checklists can reduce errors and ensure smooth submission processes. For areas or locations with limited internet access, platforms should allow submission of text-based summaries or zipped file bundles as alternatives, ensuring that students are not disadvantaged due to connectivity issues.

Keywords: ePortfolios, Student Assessment, Student Teachers, Teaching Practice, Connectivity Challenges, Zimbabwe, Higher Education

INTRODUCTION

In contemporary higher education, there is a growing emphasis on authentic assessment methods that holistically capture student learning and development. ePortfolios have emerged as a powerful tool in this regard, offering a dynamic and learner-centred approach to assessment that aligns with constructivist and reflective pedagogies (Priyamvada, 2024; Evangelou, 2023; Morris et al., 2025; Bhardwa, Zhang et al., 2025). Unlike traditional assessment methods that often focus on summative outcomes, ePortfolios enable the documentation of learning processes over time, encouraging students to be engaged in self-reflection and critical thinking.

With ePortfolios, there is “elimination of stress developed from physical assessment, [but] introspection of one’s personal teaching, teaching in the natural setting, enhancement of one’s teaching skills and techniques” (Hahlani et al., 2024, p. 2869), and the integration of knowledge across disciplines (Barrett, 2007). The ePortfolios also provide educators with richer and more comprehensive evidence of student achievement and growth, facilitating both formative and summative evaluation. As digital technologies continue to shape educational practice, understanding effective methods for implementing and assessing student learning through ePortfolios is essential in order to promote meaningful learning experiences and foster lifelong learning skills (Butakor, 2024).

Accordingly, the research questions that are addressed in this study are:

- How do ePortfolios enhance the assessment and evaluation of students on teaching practice?

- What is the evidence of teaching practice learning outcomes provided through ePortfolios?

LITERATURE REVIEW

ePortfolios have gained increasing attention in educational research as a means of enhancing both assessment and student learning (Lam, 2021; Lam, 2020). Rooted in constructivist theories of learning, ePortfolios support the active construction of knowledge by allowing students to collect, reflect upon, and showcase their learning over time (Zeichner & Wray, 2001). The ePortfolios dominated in the era characterised by the innovation pillar of higher education in the world (Walland & Shaw, 2022). Unlike traditional testing methods, ePortfolios emphasise formative assessment and continuous development, offering educators richer insights into student progress (Tosh et al., 2005) in the universities in Zimbabwe. The use of ePortfolios for formative and summative assessment usually came as a product. That is, the ePortfolios are used after the pre-service teacher has taught.

One of the central strengths of ePortfolios lies in their ability to promote reflective learning.

Digital tools used in ePortfolio creation also align with 21st-century skills, fostering competencies such as digital literacy, communication, and critical thinking. However, successful implementation depends on institutional support, educator training, and the integration of clear assessment rubrics (Lorenzo & Ittelson, 2005). The literature suggests that ePortfolios, when thoughtfully designed and integrated, offer a robust method for assessing student learning in diverse educational contexts.

Assessment and Evaluation

The term ‘assessment’ is often confused and confounded with the term ‘evaluation’ (Yambi, 2024, p. 3722). Therefore, it is imperative to delineate the terms before grappling with them.

Evaluation refers to “judging the quality of a performance or work product against a standard.” The term “evaluation” denotes the judgmental character of the process undertaken (Yambi. 2024). There is need of a benchmark to be used as a carryout evaluation.

Yambi (2024, p. 3722) defines assessment as an appraisal of a process or product. That is, when a “mentor values helping a mentee and is willing to expend the effort to produce quality feedback that will enhance the mentee’s future performance.” Yambi (2024) views assessment as a collaborative enterprise between the mentee and mentor in order to produce quality feedback that will positively influence the mentee’s future performance. In this study the mentee refers to the pre-service student teacher and the mentor refers to the established qualified teacher helping to supervise and assess the student teacher’s professional development. Assessments are developed by a plethora of groups and individuals such as teachers, district administrators, universities, private companies, state departments of education, and other groups that include combinations of these individuals and institutions (Yambi, 2024). In this study, the assessment of pre-service teachers on teaching practice involves both the enrolling university where the student is enrolled and the host school where the student is attached. It is a collaborative assessment process where the resident mentor assesses the student on teaching practice using physical face-to-face assessment, whereas the university supervisors use the ePortfolio information as data to produce a teaching practice (TP) assessment document (crit).

Yambi (2024) identify four components of the assessment process, which are measuring improvement over time, motivating students to study, evaluating the teaching methods, and ranking the capabilities in relation to set targets. It is important to note that the instruments used to assess the ePortfolios of the pre-service Science and Mathematics teachers on teaching practice depict all four key components.

Assessment is an important component of teacher training. The student teachers tend to focus on their teaching practice best because they want to pass the level (Yambi, 2024). There seems to be limited literature that addresses the issue of assessment ePortfolio for students on teaching practice, in particular on undergraduate pre-service student teachers in Zimbabwean universities. Usually the ePortfolio is submitted after students have finished or returned from teaching practice. In the Zimbabwean context the ePortfolio is a product presented for assessment and evaluation. The pre-service student teacher prepares the ePortfolios without proper guidance from the mentors.

Huckle et al. (2021) observe that there were some assessment approaches that were used in Maine’s Department of Educationsuch as competency-based assessment was used in New Hampshire, proficiency-based assessment was used in Vermont’s Agency of Education, authentic assessment was used in Maine’s Department of Education, and formative assessment was used. These approaches were implemented mainly at the primary and secondary school education levels. The authentic assessment implies the students apply their learning in the real-world context. The mathematics students and the pre-service mathematics student teachers apply their learning in the real world. For example, in the Zimbabwean context there are challenges with regard to public transport scheduling around the cities. The students and the student teacher will create a public transportation schedule “that accounts for hourly fluctuations in ridership, number of buses/trains [taxis/ kombi/ tsviriyo/ private cars] available, and relevance targets.” (Huckle, et al., 2021, p. 5). The mathematical concepts that can be applied in real-world situations are linear and integer programming for determining the number of buses needed per hour. This can also be used on how to schedule buses so costs (i.e. fuel, labour) are minimized while meeting service requirements.

The scheduling algorithm helps to plan bus/driver schedules to minimize overlaps and ensure efficient rest periods. Simulation modelling is used to model real-life systems such as passenger flow, impact of schedule changes, and delay recovery. Lastly, the network optimization/ graph theory is useful in route planning, such as determining the shortest paths and designing efficient bus routes. However, we could find limited literature that indicated how the assessment approaches were used in the assessment of university pre-service Mathematics and Science student teachers on teaching practice in the form of ePortfolios. The assessment approaches were applied in the school education context. There is limited literature on how ePortfolios can be used as assessment approaches in universities.

Huckle et al. (2020) note that in the 2020-2021 academic period, several schools relied on alternative measures to assess students, including thoughtful approaches designed to fit the educational realities of remote and hybrid learning (Therriacult, 2020). For example, use of student capstones, reflections, or portfolios served as meaningful demonstrations of learning, allowing educators to evaluate not only content mastery but also critical thinking, creativity, and personal thinking in a more flexible and context-sensitive manner (Martinez, 2020; Weingarten, 2020). Previous studies (Butakor, 2025; Sanusi et al., 2025; Modise & Vaughan, 2024;) have reported the use of alternative measures to assess students, especially those on remote and hybrid learning, yet there is limited literature that focuses on ePortfolios as assessment and evaluation methods for pre-service teachers on teaching practice. This study sought to add literature to the under-researched area of assessment and evaluation methods for ePortfolios in higher education and in a third-world context.

Huckle et al. (2021) suggests the use of competency- and proficiency-inspired assessment approaches and methods. Competency and proficiency assessment methods prioritise the substance of student work over seat time. This also complements remote learning by providing flexibility to students who face electricity load shedding and technological hurdles (Greene, Kaapp & Quick, 2020). The current studies do not explicitly refer to assessment of pre-service student teachers on teaching practice who were assessed using ePortfolios.

Teaching Practice in Zimbabwean Context

Gujjar et al. (2011) argue that teaching practice has an important place in teacher training. It is the period when the student teacher marries the theoretical and practical aspects of teacher training. Hahlani et al. (2024)’s study focused on teaching practice assessment by video, whereby the scholars grapple with the issue of challenges associated with using videos during teaching practice. The literature available rarely addresses the issue of assessment and evaluation methods employed when using ePortfolio in the assessment of pre-service student teachers on teaching practice.

For this study the term “teaching practice” is going to be used. Teaching practice refers to a period of twelve months wherein a student teacher is attached to a school and a mentor who assists the student teacher to learn teaching and professional skills.

The terms ‘practice teaching’ and ‘teaching practice’ seem to be confused and confounded such that one cannot easily distinguish them. The term “practice teaching” embraces the practicing of teaching skills and acquisition of the role of a teacher, that is, the whole range of experiences that students go through in schools as well as the practical aspects of the course as distinct from theoretical studies (Gujjar et al., 2011). On the other hand, teaching practice refers to the preparation of student teachers for teaching by practical training. It is the practical implementation of “teaching methods, teaching strategies, teaching principles, teaching techniques, and practical training and practice/exercise of different activities of daily school life” (Gujjar et al., 2011, p. 303). Traditionally, supervisors or lecturers usually made physical visits and used formative and summative assessment tools to assess and evaluate the student teachers on teaching practice, and they still run concurrently with online assessment. It was a total procedure where both the lecturers and mentors visited the classes and observed the student teacher practicing. However, with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic and the post-COVID-19 adoption and adaptations of ePortfolios’ advantages, the mentors in schools now have physical face-to-face assessment and evaluation of the students. Currently, the lecturers, or university supervisors, mostly rely on ePortfolios to assess their students on TP. The scholars who studied ePortfolio as a new dimension in the assessment and evaluation of student teachers on teaching practice focused mainly on challenges at the expense of the assessment and evaluation methods in ePortfolios. This study focuses on the ePortfolios’ assessment and evaluation methods used on pre-service student teachers on teaching practice.

MODELS OF TEACHING PRACTICE IN THE ZIMBABWEAN CONTEXT

In the Zimbabwean context, several models of teacher training are used depending on the qualifications to be obtained. Initially, the Zimbabwe Integrated National Teacher Education (ZINTEC) (Maguraushe, 2015) there was the 2-5-2 programme (2 Zimbabwean terms on college campus, 5 Zimbabwean school terms on teaching practice and the finally 2) Zimbabwean school terms on campus), which was introduced by the Zimbabwe government in 2002 as a merger of the Zimbabwe Integrated Teachers’ Education Course programme (ZINTEC) and the conventional model of training 3-3-3 (3 Zimbabwean terms on college campus, 3 Zimbabwean school terms on teaching practice, and finally, 3 Zimbabwean school terms on campus). This programme runs concurrently with the 2-1-3 programme (2 Zimbabwean terms on college campus, 1 Zimbabwean school term on teaching practice, and then finally, 3 Zimbabwean school terms on campus) (Chinengundu et al., 2022). These were for diploma programmes.

There are also teaching practice models for Zimbabwe universities that offer degrees and diplomas to pre-service student teachers. Universities in Zimbabwe use semesters. The semesters are six months long each. Such universities use the 3-2-1 model for diploma programmes, which means the first three (3) semesters are on campus, two (2) semesters are out on teaching practice, and one (1) final semester is back on campus. For the degree programme it is a 4-2-2 model, which entails starting with four (4) semesters on campus and two semesters of teaching practice, but these two semesters in a Zimbabwean university translate to three school terms and the other two back on campus.

THE E-TEACHING MODEL

The E-Teaching practice model was used as a theoretical framework. “The E-Teaching Practice is a smart learning system that communicates and cooperates with student teachers during their work-related practicum period” (Gwizangwe et al., 2019, p. 2).

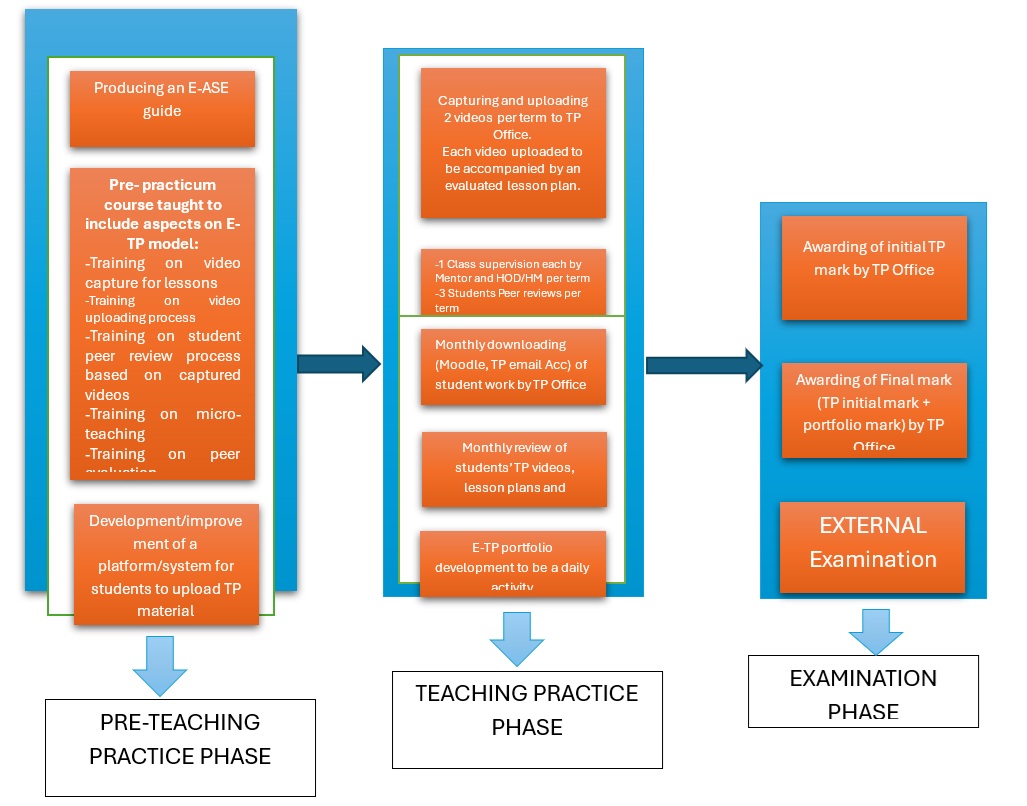

Figure 1

The E-Teaching Practice Model (adopted from Gwizangwe et al., 2019, p. 2)

The E-Teaching Practice model was used in this study to understand the use of ePortfolios in the assessment and evaluation of pre-service Science and Mathematics student teachers’ learning and teaching while on teaching practice. The E-Teaching theoretical framework assumes that the pre-service Science and Mathematics student teachers receive pre-teaching practice preparations. The students are taught aspects of the E-teaching practice model, such as training on video capturing, peer review process based on videos captured, micro-teaching, and peer evaluation (Gwizangwe et al., 2019). The students are introduced to the assessment methods and evaluation methods, such as peer evaluations.

The E-teaching practice model assumes that during teaching practice the pre-service Science and Mathematics student teachers will upload a video to the Teaching Practice office accompanied by a peer review assessment and evaluation report (Gwizangwe et al., 2019). The assessment and evaluation method suggested is the peer review assessment method. In this case, the peer assessments and evaluations will be done by the student teacher and the head of department, mentor, and headmaster/mistress of the host school. The student teacher will create an ePortfolio that is going to be submitted to the Teaching Practice office.

Lastly, the university supervisors and/or teaching practice coordinator will use summative assessment and evaluation as an examination process. Gwizangwe et al. (2019) argue that the examination phase involves a continuous and cumulative process. The school-based and faculty assessments are done and captured on the students’ profiles each term. These contribute to the initial mark. According to Gwizangwe et al. (2019, p. 4), “The initial mark and the ePortfolio mark are combined to give a final mark.”

The ePortfolio

The term “ePortfolio” is elusive to define. It is a multifaceted term in the academic field. While a variety of definitions of the term “ePortfolio” have been suggested, this chapter will use the definition suggested by Modise and Mudau (2021) that saw it as both a process and product. ePortfolio as a process allows students to move beyond learning for the sake of learning and apply the knowledge, skills, and values to the real world. The implication is that ePortfolio refers to a space where “more flexible forms of computer-based assessment are aligned with measuring knowledge skills that students need to function in an evolving digital age” (Modise et al., 2021, p. 2). This understanding of ePortfolio indicated that “ePortfolio” refers to the whole process, documented and undocumented electronically, of what transpired in the classroom setup. In these cases some of the proxy and events, such as the hidden curriculum, should be captured in the electronic file. In this study the term denotes another dimension. Gwizangwe et al. (2019) define the ePortfolio as “the electronic version of the teaching practice file; the ePortfolio has additional components such as lesson videos, electronic reference materials, and cloud backup, among others.” The ePortfolio actually profiles the student teacher’s teaching and professional development. In the Zimbabwean context, the term “ePortfolio” is viewed as a product of learning and teaching. It is a product of the work done by the novice pre-service student teacher who is on teaching practicum. The scholars seem not to agree on a common definition; therefore, a working definition is suggested for this study carried out in the Zimbabwean context. ePortfolio refers to a product of the teaching and learning activities carried out by the student during teaching practice and is presented as an electronic file with different folders assigned by the institution or university.

METHODOLOGY

This study employed a qualitative case study design (Creswell & Poth, 2023) to explore how ePortfolios were used to assess student learning and development in a higher education context. The study involved ten undergraduate students, one lecturer from the Faculty of Education at a Zimbabwean university and one Head of Department from a particular school see Table 1. The ten participants were the only students available who used ePortfolio at the selected university. Generally, there are few students who major in Science and Mathematics education courses in Zimbabwean universities. Participants were purposively selected based on their use of ePortfolio as part of the two semester-long Teaching Practice courses. One university lecturer directly involved with Teaching Practice coordination was purposely selected for a semi-structured interview.

Table 1

Participants selected for the study (created by Authors)

|

Participants |

Number |

|

Student teachers |

10 |

|

Lecturer |

1 |

|

Head of Department |

1 |

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, observation, focus group discussion, and content analysis of students’ ePortfolios. Interviews explored assessment and evaluation methods used for assessing student learning and development through ePortfolio during teaching practice. The interviews were also used to find the evidence of learning outcomes through ePortfolio during teaching practice.

Thematic analysis was used to code and interpret the qualitative data. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework guided the analysis process. Trustworthiness was ensured through triangulation, member checking, and detailed audit trails by the researcher. Here, triangulation involved using multiple sources and methods and cross-checking and validating the findings. For example, the researcher combined and compared data gathered through interviews, observations, and document analysis on the TP phenomenon. The main purpose was to reduce bias and increase the credibility of the results, as argued by Smith and Noble (2025). Member checking included involving participants in the verification of the data and interpretations. After data was analysed, the researcher asked the participants to review the theme summaries and confirm accuracy. The purpose was to ensure that the findings accurately reflected the participants’ perspectives and experiences.

Detailed audit trails involved keeping comprehensive documentation of all research steps, decisions, and data. The researchers had recorded how codes had been developed and how decisions had been made during analysis, as well as how themes were formed. This would allow other researchers to trace the research process, thus enhancing dependability and confirmability. By using triangulation, member checking, and audit trails, the researchers increased confidence that the data had been accurately interpreted, the process had been transparent and consistent, and the findings were unbiased.

Ethical approval was obtained from the university’s research ethics committee. Informed consent was secured from all participants, and anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The analysis of data collected from only ten participants selected for this study to gain access to ePortfolios through semi-structured interviews, content analysis, and focus groups revealed several key findings regarding how ePortfolios contributed to the assessment of student learning and development. The results are presented according to emerging themes:(1) Evidence of learning progression from content analysis, (2) Development of reflective practice from content analysis and semi-structured interviews, (3) Enhanced student engagement from observation and content analysis, and (4) Challenges in implementation from semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions.

Assessment and evaluation methods for ePortfolios

1.Peer assessment and evaluation methods

The findings revealed that there were peer assessment and evaluation methods used to assess and evaluate the ePortfolios of pre-service Science and Mathematics student teachers. The peer assessment and evaluation methods were effectively used in the assessment and evaluation of ePortfolios and even during the time of creating ePortfolios in the schools during teaching practice. The evidence from the study indicated that all the participants had some peer-reviewed assessment critiques that indicated that the peer assessment and evaluation method was being used to assess and evaluate the ePortfolios. It was mandatory for the ePortfolios to have a critique from peers. In this case, the peers were the heads of department (HODs), mentors, and headmasters (HMs). Participant A’s peer review critic reads, “The teacher linked the lesson to pupils’ knowledge very well and was also appropriate.”

The peer review had been done by the Head of Department (HOD), whose report was part of the assessment and evaluation of the ePortfolios. The HOD further critiqued that “The learners’ level of participation was very good, but the teacher needs to have more classroom pupil-to-pupil interaction. This is because learners also enjoy and are interested in learning by themselves.” (Participant A ePortfolio). The comments on Participant A’s critique confirmed Cabello and Topping’s (2020, p. 122) observations, where they say peer assessment is a “form of evaluation that is designed for enhancing learning.” The comments on the critique, which encouraged the student teacher to improve on the group work method, revealed that the peer assessment and evaluation method of ePortfolio enhanced teaching and learning for the pupils and the pre-service student teacher.

The peer assessment for participant B was carried out by the Head of Department in the school because he is the one who focused on the documentation. The reports on Participant B’s critique state that “the scheme aims and objectives are well stated with lessons clearly specified. A variety of teaching resources were given. A total of 3 tests have been given and marked to date, and a record of learners’ marks is available.” The peer review assessment and evaluation method for ePortfolio helped the student teachers to grow professionally by giving remarks on the documentations. The findings confirm Cabello and Topping’s (2020) assertion that peer assessment provides the teacher with an opportunity to critically reflect on their conceptions about teaching, their practices and documentations, and peer practice. Peer assessment (Topping, 2009) and the evaluation method for ePortfolio are strategies that helped the student teachers to examine their progress in their teacher training.

2. Formative assessment and evaluation methods

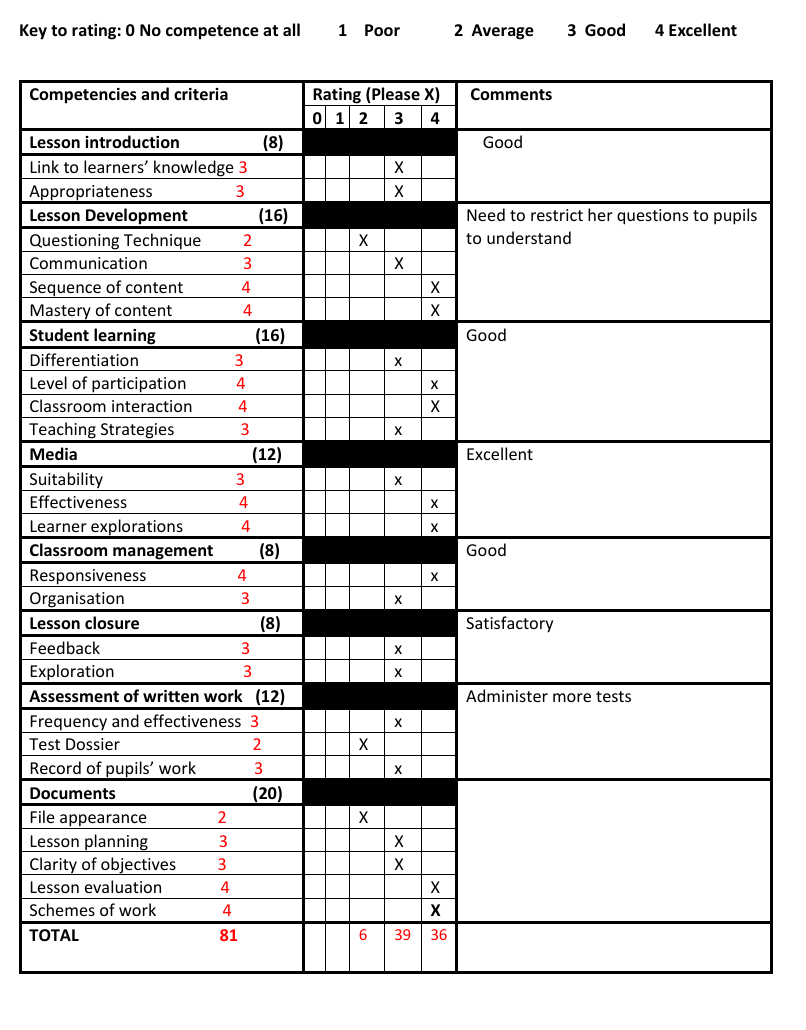

The formative assessment and evaluation method for ePortfolio is one of the methods widely used in the assessment and evaluation of ePortfolio in higher education contexts. The student teacher will have a task to deliver as a lesson. The mentor or head of department will complete a form in order to give an assessment of the lesson. The findings reveal that there was a form that was completed after a lesson delivery, and the form would have the ratings from poor, average, good, and excellent.” Yang, Tai and Lim (2015, p. 1) state that “ePortfolios are a form of authentic assessment with formative functions that include showcasing and sharing learning artefacts, documenting reflective learning processes, connecting learning across various stages, and enabling frequent feedback for improvement.” This confirms Yang et al. (2015) buttressed that the formative assessment and evaluation as a method aims at informing and assisting student teachers’ ongoing learning progress. The evidence from Figure 2 confirmed that the formative assessment method is used to help the “learning process by providing feedback to the learner, which can be used to identify strengths and weaknesses and hence improve future performance” (Wong & Yang 2017, p. 3). The assessment instrument in Figure 2 indicated that the formative assessment method was used as an assessment and evaluation method for ePortfolio in the educational context.

Figure 2

A formative assessment instrument

This form was part of the ePortfolio. The supervisor assessed lesson delivery. A dominant theme across interviews was the development of reflective thinking. Students used their ePortfolio not just to document tasks but to critically analyse their teaching experiences. One student remarked:

“The ePortfolio made me think deeply about what went wrong in a lesson and how I could improve next time.”

Lecturers confirmed that the level of reflection improved significantly over time, with more nuanced and personal insights in later entries compared to initial submissions. This reflective process aligned with learning outcomes related to professional growth and self-assessment.

3. Summative assessment and evaluation methods for ePortfolios

The results revealed that a summative assessment and evaluation method was used to assess and evaluate the ePortfolio for teaching practice. From the E-teaching practice model, the examination of teaching practice was done through assessing and evaluating the submitted ePortfolios. In this case, the ePortfolio tool contained the timetables, lesson plans, schemes of work, lesson videos, school syllabi, national syllabi, test dossiers, records of marks, practicum assessment records/profiles, practicum hand-outs, and resource materials (Gwizangwe et al., 2019, p. 5). The ePortfolio is a collection of what happened during the entire period when the student teacher was attached to teaching practice. The university supervisors/lecturers or coordinators assessed and evaluated the ePortfolio for grading to come up with the final teaching practice grade. In this case the summative assessment and evaluation methods were used. Wong and Yang (2017) argue that summative assessment is used solely for grading or determining readiness for progression.

All student ePortfolios demonstrated a clear trajectory of learning over the course of the academic year. Students included multiple artefacts such as lesson plans, video reflections, feedback from supervisors, and self-evaluations. These artefacts showed growth in both content knowledge and pedagogical skills. Lecturers noted that the ePortfolio provided “comprehensive snapshots” of how students applied theoretical concepts in practice. This was especially evident in how students adapted their teaching strategies based on classroom experiences and feedback.

Students reported feelings of a greater sense of ownership over their learning. The flexibility of choosing artefacts and writing reflections in their own voices allowed student teachers to express individuality and creativity. Several students mentioned that ePortfolios encouraged them to take their work more seriously because they were building a record of personal and professional development. Lecturers also found that students who actively engaged with their ePortfolios demonstrated increased participation in class discussions and mentoring sessions.

4. Collaborative assessment and evaluation method

The collaborative assessment and evaluation method for ePortfolios was used during teaching practice in Zimbabwe. Participant F said that sometimes the mentor assisted her in the assessment and evaluation of her ePortfolio. She added that the mentor also helped her to edit videos.

The findings revealed that some mentors collaborated with the student teachers in the assessment and evaluation of ePortfolios. It was a collaborative assessment process where the resident mentor assessed the pre-service student teacher on teaching practice (Yambi, 2024; Fine & Pryiomka, 2020). The mentor used the physical face-to-face assessment through observation and the portfolios, whereas the university lecturers relied more on ePortfolios to assess the students. In this case, the mentor used a collaborative model of supervision.

Challenges in Implementation

Despite the benefits, both students and lecturers encountered challenges. The most common issues were technical difficulties, inconsistent feedback, and time constraints. Some students struggled with organising content or using the digital platform effectively. Lecturers reported encountering similar challenges during document analysis. Lecturers noted that providing detailed, timely feedback through the ePortfolio system was demanding, especially with large class sizes. Lecturer A stated:

“It’s a valuable tool, but we need more structured support and training to implement it efficiently. The videos sent by students are also very artificial; they show part of the classroom, and we would want blended supervision and maybe visit the student teacher once for face-to-face interaction. You know we are from the old school. The other thing is that there are network challenges and technical difficulties when some videos are formatted in such a way that you cannot open them for assessment, and others are not audible and clear, just dark. Giving timely feedback through the ePortfolio is demanding, and you need internet and electricity.”

The ten videos analysed and sent for assessment were showing parts of the class; it was not a full view of the classroom. The whole class was not being shown. This was because the participants used cameras from phones instead of using drone cameras. The phone camera does not capture every student nor every part of the classroom. The phone camera just captured where the person holding the camera focused on. This will not show what was really taking place in every part of the classroom, which could be seen when the assessor is physically in the classroom. As an electronic assessor, you just assess part of the class and not the whole class, unlike what is seen during a face-to-face situation. Other videos could not be viewed easily, which became a challenge for the assessors.

From the ten videos analysed, only two videos were showing the captured parts clearly. The other six were dark and of poor quality. There was too much darkness in the classroom, to the extent that you could rarely see the student teacher and the students. Hence, you cannot see what they are doing during group discussion activity. The videos were also not audible. You could hardly hear the student teacher’s voice and the student teacher’s presentation and the feedback during class discussion.

Moreover, even if the lessons were 35 minutes each, one hour, or 70 minutes, the videos sent were of a length less than 26 minutes. This means that some parts of the lessons were not captured. Some videos did not have an introduction or even a conclusion.

The students filmed during the lessons appeared too artificial. In most videos every student seemed to know the answers even before the student teacher had finished asking the questions. All the students required definitions in the lesson for that particular topic. It seemed most student teachers used revision lessons for their assessment. Observations of the videos suggested that student teachers video-recorded a repeat of the lessons they had previously taught since all the students seemed to have grasped most of the concepts being taught. It would appear the learners would have discussed while referring to their notebooks and then present the correct answers without any difficulty.

Of the two ePortfolios assessed, one student teacher’s video included a song by a certain artist, while the other student’s had no video attached. Some fail to include lesson plans, schemes of work and assessment feedback from the mentor and the school head (principal of the school) or the head of department.

The findings of this chapter reinforce the growing consensus in the literature that ePortfolios are a valuable tool for assessing both cognitive and developmental aspects of student learning. Consistent with Barrett (2007), this study found that ePortfolios promote reflective practice, enabling students to critically engage with their learning experiences and track personal and professional growth. The findings also point to the broader pedagogical shift towards authentic and student-centred assessment models, in line with constructivist principles (Shepard, 2000). By encouraging students to document learning in real-world contexts and reflect on their evolving competencies, ePortfolios contribute to the development of lifelong learning habits and professional identity formation. Challenges identified in this study align with those reported by Buzzetto-More (2010) and Lorenzo and Ittelson (2005).

CONCLUSION

This chapter explored the use of ePortfolio as a method for assessing student learning and development in a higher education context. Some of the assessment and evaluation methods for ePortfolio were formative, summative, and collaborative and peer review methods. There is limited literature on the aspect of the method of assessment and evaluation of ePortfolios in the post-Covid-19 era. The findings highlighted that ePortfolios offer a holistic and learner-centred approach to assessment, enabling students to document their academic growth, reflect critically on their experiences, and engage more actively in their own learning journeys. The study also demonstrated that ePortfolios served as valuable tools for educators, providing rich, longitudinal data on student performance that went beyond traditional testing metrics.

Importantly, the integration of reflective practices through ePortfolio use has been shown to foster deeper learning, promote self-awareness, and support the development of key graduate attributes such as critical thinking, digital literacy, and professional accountability. However, challenges such as limited technical support, inconsistent feedback mechanisms, and time constraints underscored the need for strategic planning and institutional support to ensure effective implementation.

While ePortfolios are not a one-size-fits-all solution, they represent a meaningful shift toward more authentic, formative, and developmentally focused assessment practices. Future research should investigate scalable models for ePortfolio integration across disciplines, as well as strategies to support both students and educators in maximising their potential. The results showed that ePortfolio can serve as an effective tool for assessing student learning and professional development when used thoughtfully. They promote reflection, showcase progression, and engage learners meaningfully, though successful implementation requires addressing technical and logistical barriers.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the findings of this study, several key recommendations are proposed to enhance the effective use of ePortfolios in assessment and evaluation practices. Institutions should offer ongoing training for both students and educators on how to use ePortfolio platforms effectively. This includes technical guidance, reflective writing workshops, and best practices for selecting and curating portfolio content. To ensure consistency and fairness, assessment rubrics should be developed and communicated clearly. These rubrics should evaluate not only content knowledge but also reflection quality, progression, and creativity. Educators need support in managing workload to provide timely, meaningful feedback on ePortfolio entries. Consideration should be given to smaller feedback loops or peer-assessment opportunities to alleviate pressure and enhance engagement. Curriculum designers should embed reflective practices into course outcomes to normalise and encourage ongoing self-assessment.

REFERENCES

Barrett, H. (2007). Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: The REFLECT initiative. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(6), 436–449.

Bhardwaj, V., Zhang, S., Tan, Y.Q., & Pandey, V. (2025).Redefining learning: Student-centred strategies for academic and personal growth. Frontiers in education.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Butakor, P. (2024). Use of ePortfolios as a Teaching, Learning, and Assessment Tool in Higher Education: Differing Opinions among Ghanaian Pre-Service Teachers and Nurses. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy. 5. 35-45. 10.24018/ejedu.2024.5.6.858.

Buzzetto-More, N. A. (2010). Assessing the efficacy and effectiveness of an ePortfolio used for summative assessment. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, 6(1), 61–85Cabello, V.M. & Topping, K. (2020) Peer assessment of teacher performance: What works in teacher education? International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering, and Education, 8 (2), 121-132.

Chinengundu, T., Hondonga, J. & Mhazo, F. (2022) Teaching practicum assessment procedures adopted by primary teachers’ colleges in Zimbabwe. Teacher Education through Flexible Learning in Africa (TETFLE) 3 (1) DOI:10.35293/tetfle v3i1.3709

Creswell, J.W. & Poth, C.N. (2023). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE Publication

Evangelou, F. (2023). Teaching techniques for developing the learner-centred approach in the classroom. European Journal of Education Studies, 10 (2), 166-192.

Fine, M. & Pryiomka, K. (2020). Assessing college readiness through authentic student work: How the City University of New York and the New York Performance Standards Consortium are collaborating toward equity. Learning Policy Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606677

Greene-Knapp, L. & Quick, A. (2020). Advancing collaboration and competency-based education during COVID-19. RTI International. https://www.rti.org/insights/advancing collaboration-and-competency-based-education-during-covid-19

Gwizangwe, I., Mhishi, M., Zezekwa, N., Mpofu, V., Sunzuma, G., Mudzamiri, E., Manyeredzi, T., Munakandafa, Chagwiza, C. J., Ndemo, Z., Kazunga, C. & Mutambara, L. N. H. (2019). E-Teaching Practice Model Administration Manual. Bindura: Bindura University of Science Education.

Gujjar, A. A., Ramzan, M. & Bajwa, M. J. (2011). An evaluation of teaching practice: practicum. Pakistan. Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences. 5 (2), 302-318

Hahlani, O. S., Chipambwa, W., Sithole, A. & Moyo, M. (2024). Teaching practice assessment by video lessons: Representations of undergraduate student teachers at a selected university in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 8(9), 2869–2877. https://doi.org/10.47772/IJRISS.2024.8090240.

Huckle, E., LeVangie, S. & Tierney-Fife, P. (2021). Region 1 Comprehensive Centre Reimagining Education Series: Approaches for assessing student learning. Region 1 Comprehensive Centre.

Lam, R. (2021). Using ePortfolios to promote assessment of, for, and as learning in EFL writing.

Lam, R. (2020). ePortfolios: What We Know, What We Don’t, and What We Need to Know. RELC Journal. 54. 003368822097410. 10.1177/0033688220974102.

Lorenzo, G. & Ittelson, J. (2005). An overview of ePortfolios. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative Paper 1:2005. https://er.educause.edu/

Maguraushe, W. (2015). Insights into the Zimbabwe integrated national teacher education course: Graduates’ music teaching competency. Muziki 12 (1): 86-102

Martinez, M. (2020). Using end-of-year assessments for learning, reflection, and celebration (Learning in the Time of COVID-19). Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/using-end-year-assessments-learning-reflection-and-celebration

Modise, M.E. & Mudau, P.K. (2021). Using ePortfolios for meaningful teaching and learning in distance education in developing countries: A systemic review.

Modise, M.P. & Vaughan, N. (2024). ePortfolios: A 360 Degree Approach to Assessment in Teacher Education. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology 50, (4).

Morris, T.H., Bremner, N. & Sakata, N. (2025) Self-directed learning and student-centred learning: a conceptual comparison. pedagogy, Culture and society, 33 (3).

Priyamvada, S. (2024). Exploring the Constructivist Approach in Education: Theory, Practice, and Implications. IJRAR, 5 (2).

Sanusi, N., Zulkifli, H., & Hamzah. (2025). Challenges, opportunities, and effects of alternative assessment approaches in teaching practices: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE). 14. 1105. 10.11591/ijere.v14i2.32283.

Smith, J. & Noble, H. (2025). Understanding sources of bias in research. Evidence-Based Nursing. 28. ebnurs-2024. 10.1136/ebnurs-2024-104231.

Therriault, B. S. (2020). Back-to-school metrics: How to assess conditions for teaching and learning and to measure student progress during the COVID-19 pandemic. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, Regional Educational Laboratory Midwest. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/midwest/blogs/back-to-school-metrics-covid.aspx

Topping, K. J. (2009). Peer assessment. Theory Into Practice, 48(1), 20-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802577569

Tosh, D., Light, T. P., Fleming, K. & Haywood, J. (2005). Engagement with electronic portfolios: Challenges from the student perspective. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 31(3).

Walland, E. & Shaw, S. (2022). E-portfolios in teaching and assessment : Tensions in theory and praxis. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31 (3), 363-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X2022.2074087

Weingarten, R. (2020). How to cap this unprecedented school year. AFT Voices. https://aftvoices.org/how-to-cap-this-unprecedented-school-year-2523445f13a6

Wong, K. W. G. & Yang, M. (2017). Using ICT to facilitate instant and asynchronous feedback for students’ learning engagement and improvements. In S. C.

Yambi, T. D. A. C. (2024). COVID-19 pandemic and the current challenges of the Angolan higher education system. Science Journal of Education, 12(4), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.sjedu.20241204.17

Yang, M., Tai, M. & Lim, C. P. (2015). The role of an e-portfolio in supporting productive learning. British Journal of Educational Technology. 47 (6). DoI: 10.1111/bjet.12316

Zeichner, K. & Wray, S. (2001). The teaching portfolio in US teacher education programs: What we know and what we need to know. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(5), 613–621.

AUTHORS

Dr. Ndemo Zacharia is a dedicated mathematics educator and chairperson of the department of Mathematics and Science Education. He holds a Ph.D. in Mathematics Education from the University of Zimbabwe. With a strong passion for teaching and research, Dr. Ndemo has spent several years in the academic field, focusing on improving mathematics instruction and promoting student-centred learning strategies.. Throughout his career, Dr. Ndemo has contributed to various academic conferences, teacher training programs, and curriculum reform initiatives aimed at raising the standards of mathematics education in Southern Africa. He is also actively involved in mentoring pre-service and in-service mathematics teachers, supporting them in developing effective teaching practices.

Email: zndemo@gmail.com

Dr. Cathrine Kazunga is a Mathematics Education expert with a strong academic background and professional experience. She holds a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Mathematics Education from the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal.. She has vast experience in teaching and training teachers and experience in primary, secondary, and tertiary mathematics. Her research interests are the teaching and learning of linear algebra, STEM education, ICT integration into mathematics teaching and curriculum interpretation, and classroom mathematics. She has the following awards from Bindura University of Science Education: best student and Vice Chancellor award (2008) and Organisation of Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD) Postgraduate Training Fellowships for Women Scientists in Sub-Saharan Africa and Least Developed Countries (2013). She had several publications and presented her work at different conferences nationally, regionally, and internationally.

Email: kathytembo@gmail.com

Dr. Lytion Chiromo is a Dean of Students at Reformed Church University. He holds a Ph.D. in Restorative Justice from the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal., He possesses a strong administrative and academic background. He has vast experience in the teaching of mathematics at primary and tertiary levels. He also has vast experience in teaching and training teachers in primary, secondary, and tertiary education. With a strong research focus, he authored articles and published papers in reputable journals. His expertise spans areas in the teaching and learning of STEM education. As a dedicated educator, he inspires students with their passion for mathematics, fostering a love for learning and academic excellence.

Email: mahunzuhunzul@gmail.com