7 Challenges and Solutions: Addressing Obstacles to the Effective Use of ePortfolios

Chantelle Melanie August-Mowers and Samantha Melissa Hoffman

Two Oceans Graduate Institute, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The chapter explores the complex dynamics of ePortfolios post-COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on their transformative nature in education and professional development. It is no secret that the COVID-19 pandemic forced all sectors, including education, to rethink their traditional approach to teaching, learning, and assessment. The rise of the fourth industrial revolution in the early 2000s was the cornerstone of the inevitable reality of the fast-approaching digital era. However, the unexpected shockwave caused by the COVID-19 pandemic undeniably fast-tracked the digital era and has catalysed unprecedented change. The disruption of the norm came with many challenges, but at the same time, it presented the education sphere with innovative and digital solutions such as the incorporation of ePortfolios. These challenges can be attributed to many factors, such as personal diversity, spatial inequalities, freedoms, and particular needs, interests, and desires at a particular time, as posited by Sen’s Capability Approach and Capability Sets. The chapter is grounded in the Capability Approach (CA), which explores the constructs of Capabilities, Functionings and Conversion, emphasising human development. The chapter extends the CA into the scope of education, using the above Capability Sets as criteria to assess teachers’ and students’ capabilities in educational settings. In this chapter, ePortfolios are viewed as a tool that can considerably enhance the teaching, learning, and assessment processes in a variety of ways (Borthwich, 2021). The study adopted a qualitative research method through a theoretical-conceptual review by exploring the potential of ePortfolios to address challenges and obstacles in assessment that condition academic performance. The chapter highlights the need to rethink the transformative nature of ePortfolios and find effective ways to harness ePortfolios to their full potential. The chapter further highlights the need to approach ePortfolios through the lens of reflexivity, as it allows participants to navigate between the past, present, and future.

Keywords: capability approach, freedoms, personal diversity, reflexivity, spatial inequalities, transformative agency, work-based learning

INTRODUCTION

The concept of assessment has gained momentum in the last decade as an important reform for promoting quality education that will advance student academic achievement, which will ultimately lead to better opportunities for life after school. It resulted in critiques of traditional approaches to assessment that hold a narrow view of testing, as it seldom considers the social, cultural, historical, and linguistic backgrounds of the students. The problem of low achievements and high dropouts was attributed to the students’ ability and not the education system’s approach to assessment and testing. The Industrial Revolution fast-tracked digital learning and at the same time forced people to rethink the perceptions of assessment practices. The chapter focuses on ePortfolios as a medium of assessment in schools to create fair opportunities for all learners, taking the holistic development of the learner into account. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss strategies to address the obstacles to the effective use of ePortfolios as a transformative tool in education that will enable students to achieve academic functions important to them. This discussion starts with the conceptualisation of ePortfolios, the Capability Approach to frame ePortfolios, obstacles for the effective use of ePortfolios via the Capability sets, addressing the obstacles to the effective use of ePortfolios relating to the role and functions of assessment, and ePortfolios as a vehicle of transformation.

Socio-political perspective of assessment

Learner performance and output are closely linked to assessment tasks and examinations. Assessment is a widespread phenomenon and is often misunderstood in current educational practice (August, 2023). Assessment forms the systematic basis to interpret the learning, development, and academic performance of the students (Bisai & Singh, 2018). In other words, assessment can be viewed as a “controlled social practice because it influences student learning and education in general” (Taras, 2008, p. 289). Different tools are used in assessment to promote children’s literate behaviour, and these tools are powerful because of their technical role to ‘develop accurate measuring instruments’ (Johnston & Costello, 2005). Schools use these “almost always standardised measurement devices or accountability assessments” to ascertain the effectiveness of educational endeavours, such as academic performance (Popham, 2009, p. 6). The danger of using such measurement devices is that they adopt a one-size-fits-all approach and often disregard the holistic performance of a child.

The bifurcation of South African society and the schooling system is not only reflected in classroom monolingual practice but is evident in student achievement. The focus of pupil performance assessments in the past was results-driven and was seen as a major educational issue (Marshall, 2017). For the past two decades, views on tests have changed to a socio-political perspective due to their scientific and technical nature in which they operate, i.e., the social, political, and economic context. The change in view came because tests are seen as a determining, powerful device rather than a measuring tool (Shohamy, 2011). In many instances, this socio-political perspective gives rise to the apartheid ideologies that were geared at non-whites to receive an inferior education that does not prepare them for technological, engineering, and scientific advancement (Makoelle, 2009). In South African schools today, the Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement models the view of the constitution that aims to rectify the inequalities of the past (DBE, 2011). The Assessment of the National Curriculum Statement Grades R-12 highlights the importance of assessment (DBE, 2011) and stipulates that:

- Assessment is a process of collecting, analysing and interpreting information to assist teachers, parents, and other stakeholders in making decisions about the progress of learners.

- Classroom assessment should indicate learner achievement most effectively and efficiently by ensuring that adequate evidence of achievement is collected using various forms of assessment.

The role and purpose of assessment is thus important because of “its potential to influence the entire reform process,” which is aimed at improving knowledge, skills, and attitudes. In doing so, formative and summative assessments were introduced (DBE, 2011). The assessment policy in the General Education and Training (GET) Phase (DBE, 2011) states that assessment has multiple purposes and is aimed at:

- Helping learners select learning programmes or careers;

- An educator trying to place a learner in an appropriate grade/level; and

- A parent wants to know how the learner is progressing.

From a language perspective, historically, assessment was linked to an overarching context that restricted choices around languages, which favoured monolingualism as the standard language (Schissel, De Korne & López-Gopar, 2018). Shohamy (2011, p. 418) outright claims that “all assessment policies and practices are based on monolingual constructs whereby test-takers are expected to demonstrate their language proficiency in one language at a time. Thus, the construct underlying these assessment approaches and/or scales is of language as a closed and finite system that does not enable other languages to be “smuggled in.” The narrow nature of these assessment activities often generalises because it is mostly used in the traditional assessment system, which focuses on producing facts. Engaging in the traditional practices is exclusive in nature, as it often disregards or fails to measure holistic learning outcomes (Bisai & Singh, 2018, p. 308). Moreover, the perception is often that testing and assessing are the same, but they are not. Brown distinguishes between test and assessment in the following way.

Tests are prepared administrative procedures that occur at identifiable times in a curriculum when learners muster all their faculties to offer peak performance, knowing that their responses are being measured and evaluated. Assessment, on the other hand, is an ongoing process that encompasses a much wider domain, such as whenever a student responds to a question, offers a comment, or tries out a new word or structure, the teacher subconsciously assesses the student’s performance (Brown, 2016, p. 15).

While assessment practices are viewed as an integral part of academic progress and achievement by scholars (Aboulsoud, 2011; August, 2023), it is crucial to understand that assessment should be developed to recognise the holistic nature of a child and support them in the assessment context. As such, the nature of ePortfolios is to facilitate collaboration and input from both teachers and learners, strengthening feedback on the side of the teacher and development on the side of the learner (Borthwich, 2021). If assessment is deemed effective, it should be balanced, comprehensive, time-efficient, manageable, varied, valid, and fair (DBE, 2011). By approaching assessments with the above-mentioned principles, we can validate students’ competencies at different levels.

Assessment for learning vehicle for ePortfolios

ePortfolios seem to be a promising avenue to address the challenges of assessments that often disregard the holistic development of students. Moss (2008) contends that assessment for learning is linked to socio-constructivist theories of learning because it is seen as a socially situated activity. Naturally, assessment for learning extends beyond the confined boundaries of the classroom because of its nature to observe a wide variety of contexts (Jordan & Putz, 2004). The early 1990s saw a rise in interest in assessment of learning as over-assessment of learners was heavily debated. Cambridge Assessment International Education (2019) highlighted that learners were exposed to too much testing to ascertain learners’ academic performances and ability to make comparisons between rank order.

Assessment for learning can take on many forms because it is associated with different forms of assessment, including formative assessment, classroom assessment, continuous assessment, and informal assessment. In addition, assessment for learning is viewed as tasks that “are carried out by teachers and students as part of day-to-day activity” (Browne, 2016, p. 1). Scholars supporting assessment for learning view it as a critical component of effective instructional practice (Ruiz-Primo, 2011, p. 15). To add, it highlights AFL as an informal, informative assessment due to its nature that allows teachers and students to reflect on what they do in the classroom. This “can be described as potential assessments that can provide evidence about the student’s level of understanding” (p. 15).

ePortfolios align with the concept of assessment for learning, as this is an approach that integrates various activities in teaching and learning, which create fundamental opportunities for feedback to students for improvement in their learning (Cambridge Assessment International Education, 2019).

Similar to the concept of ePortfolios, assessment for learning, with its informal formative assessment nature, focuses on the daily learning activities as potential assessments that provide evidence of students’ learning in different modes” (Ruiz-Primo, 2011, p. 15).

The list below is illustrated by Ruiz-Primo (2011, p. 15). demonstrates the different learning methods, which can be included in assessments and ePortfolios.

- Oral evidence (e.g., students’ questions and responses, listening to what they say in small groups, having conversations with students);

- Written evidence (e.g., notes in science notebooks);

- Graphic evidence (e.g., drawing, graphs, concept maps);

- Practical evidence (e.g., observation of students experimenting to measure the mass of an object); and

- Non-verbal evidence (e.g., body language, body orientation). Moreover, assessment for learning also involves collaborative learning activities, which include peer and self-assessment activities, and it guides learners with their aims and their understanding of what needs to be done to achieve those aims.

Assessment for learning and ePortfolios focuses on both the teacher’s and the learners’ understanding, inculcating a culture for accepting alternative authentic displays of learners’ learning journeys, taking into account the holistic development of the learner. It is important to note that feedback is essential to the growth and development of the learner, as it places continuous improvement at the centre of the learner’s learning journey. The nature of AFL expands the opportunity of ePortfolios as it focuses on the continuous development of the student. The following section conceptualises the effective use of ePortfolios as a tool to enhance academic performance.

CONCEPTUALIZE EPORTFOLIOS

The proliferation of digital technologies gave rise to significant transformations in a global context, especially in education, particularly in response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The abrupt effects of the virus have underscored the deficiencies in traditional approaches to measuring academic performance, specifically highlighting the lack of digital skills and preparedness across the education sphere (Ndebele et al., 2024). Questions arose regarding the compatibility of the current approaches to assessment to respond to the needs of today’s learners in South African schools.

The use of ePortfolios has become a topic of interest in recent years, especially in academic spaces. The COVID-19 pandemic forced many institutions of learning to revisit their approaches to teaching, learning, and assessment. Though the Covid-19 pandemic caused havoc amongst many, it gave rise to innovative alternatives such as the ePortfolio. Electronic portfolios are classified by Pallitt, Strydom, and Ivala (2015) as “Purposeful collection of information and digital artefacts that demonstrates development or evidence of learning outcomes, skills, or competencies” (p. 2). Kok and Blignaut (2009, p. 2) explain that the nature of ePortfolios includes digital artifacts that:

- Demonstrates growth and development;

- Flexibility with expression and

- Involvement by multiple role-players

Noakes (2018) elucidates that digital and electronic learning portfolios (ePortfolios) are playing a growing role in supporting admission to tertiary studies and employment by visual representation of personal and professional development and work compiled over time. These digital resources allow users to add personal artifacts to strengthen the facilitators’ comments and customize folders and sections that address the skill requirements for certain tasks and developmental areas (Kok & Blignaut, 2009:2). The key element of ePortfolios is that they can store large volumes of information and secure confidential information and at the same time serve as a dynamic tool to enhance teaching and learning (Borthwick, 2021).

However, the usefulness of ePortfolios in a post-COVID era is still debatable and needs to be reconceptualised in professional development spaces to eliminate confusion and problematic implementation. The digital era and industrial revolution are inescapable and can no longer be seen as a “far-fetched reality.” This scenario advocates for actions that complement the digital era and support the education fraternity in a meaningful way. It is therefore imperative that practice-oriented research based on innovative digital solutions is intensified.

CAPABILITY APPROACH TO FRAME EPORTFOLIOS

The Capability Approach (CA), developed by economist Amartya Sen (1992), was used as the theoretical lens to frame this chapter to address the obstacles and solutions for the effective use of ePortfolios. CA is a central constituent of the writings of Amartya Sen and is underpinned by the following constructs: capabilities, functioning, conversion, freedoms, and unfreedoms (Sen, 1992). The capability approach, developed by Amartya Sen, asserts that people should be afforded the freedom to achieve well-being and develop their capabilities, that is, “their real opportunities to do and be what they have reason to value” (Robeyns, 2011, p. 1). Freedoms relate to people’s ability to be able to make choices that allow them to help themselves and others (Hoffman & Maarman, 2024). As such, the use of ePortfolios in education is a transformative tool. According to the CA, individuals should have certain basic capabilities that enable them to function fully as human beings. Alexander (2016) singles out the following as basic capabilities: being healthy, having access to education and employment opportunities, and having social and political freedoms. This study will specifically use the capability sets in the work of Sen to explore the obstacles and solutions to the effective use of ePortfolios.

Sen (1992) states that capability sets are sets of criteria used to assess and determine the real opportunities available to achieve valuable functionings, what a person or an institution can do or be. The capability sets include “freedoms and unfreedoms, interpersonal and inter-social variations, personal diversities, systemic contrasts between groups, the relationship between primary goods and well-being, spatial inequalities, particular needs, interests, and desires at a particular time, individual variations (abilities, predispositions, physical differences, etc.), individually valued objectives, and group-valued objectives” (Sen, 1992, pp. 27-28).

For this study, the researcher chose the capability sets relevant to the findings and context of the study because of the value and flexibility that the CA allows researchers to choose their own capability sets based on the individual spaces, goals, and circumstances of a particular subject of study (Hoffman, 2017; Hoffman & Maarman, 2024).

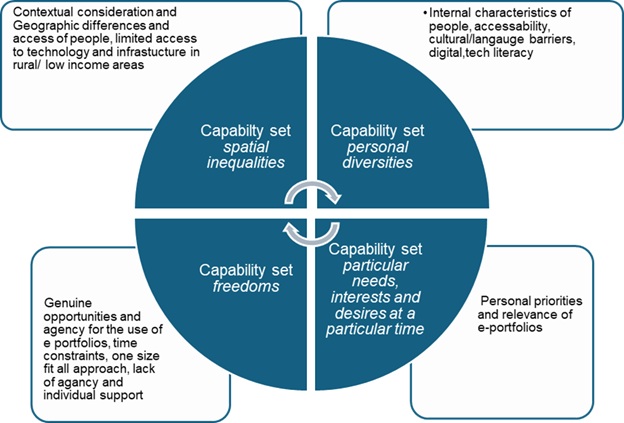

The capability sets are as follows: spatial inequality, personal diversities, particular needs, interests, and desires at a particular time, and freedoms. By using these capability sets, we can critically analyse the limitations and obstacles to the effective use of ePortfolios.

Obstacles to the effective use of ePortfolios via the Capability sets

The capacity to cater to a variety of learning styles is one of the many obstacles in epistemological access (Plüddeman et al., 2025). To mention a few obstacles: spatial inequalities, personal diversity, particular needs, interests and desires at a particular time, and freedoms. Understanding these obstacles is helpful to engage in new possibilities such as the incorporation of ePortfolios to enhance teaching, learning, and assessments in the school context. It is important to note that each obstacle is embedded within the capability sets and is discussed accordingly.

The use of ePortfolios as a vehicle for digital collections of students’ or any person’s work, learning journey, achievements, and reflections holds considerable potential in education and career development. However, when examined through the lens of the capability sets entrenched in the capability approach of Sen (1992), notable challenges and obstacles emerged, as depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Challenges and obstacles to the effective use of ePortfolios

Challenges and obstacles for ePortfolios via Capability Set: Spatial inequalities

Sen’s (1992) elucidation of Spatial inequalities suggests that some spaces are traditionally associated with claims of ‘equality’ in political, social, or economic philosophy. Further, it emphasises that we live in different natural environments – some more hostile than others. The societies and the communities to which we belong (e.g., rural and urban areas and low- and high-income areas) offer very different opportunities and access to what we can or cannot do (Sen, 1992), as in this study, access and effective use of ePortfolios. The following challenges and obstacles, as mentioned in Figure 1 but not limited to, are discussed below.

Digital inequality/gap: People in low-income communities or rural or remote regions might have limited access to reliable internet, computers, and mobile devices, which makes it difficult to create access to or maintain ePortfolios.

Infrastructure deficiency: Infrastructure remains a very tense issue in underprivileged communities. The lack of or limited access to digital platforms, lack of reliable internet connections, modern devices, and sufficient data in schools or community centres can hinder the effective implementation, use, and access to ePortfolios and ultimately the ability to engage with ePortfolio platforms meaningfully (Dlamini, 2022). In addition, Dlamini (2022) argues that students from Black working-class backgrounds frequently face challenges such as slow internet speed, shared devices, and limited access to digital tools, which impede their participation in ePortfolio activities. To add, the lack of institutional support from the government can further increase the infrastructure gap. Lack of training facilities and lack of competence can widen the gap in the successful implementation of ePortfolios.

Educational disparities: Schools in low-income or marginalised areas may lack the technological integration necessary for ePortfolio use, perpetuating existing educational inequalities.

The above limitations not only restrict access to or maintain access to ePortfolios, but they also perpetuate educational inequalities, as people without adequate resources are less able to showcase their learning and achievements digitally.

Challenges and obstacles for ePortfolios via Capability Set: Personal Diversity

According to Sen (1992), Personal Diversities acknowledge that all human beings are diverse and differ not only in external characteristics but also in personal characteristics, which will also determine their capabilities. The study revealed that people differ in terms of their external characteristics as well as personal (internal) characteristics. Individual differences can include age, gender, physical disabilities, cognitive ability, language and culture, learning styles, and tech or digital literacies.

Accessibility limitation: Electronic platforms may not be designed for users with disabilities such as visual impairments and dyslexia that may limit usability for ePortfolios.

Language and cultural barriers: people from non-dominant language backgrounds might struggle to express themselves in the language required for ePortfolio entries. As indicated by Noakes (2018), ePortfolio curricula often reflect dominant cultural norms that can marginalised people whose identities and cultural expressions differ from these norms. For example, in visual arts education, students from diverse backgrounds may feel obligated to conform to mainstream artistic standards, sidelining their unique cultural perspectives and creativity, which do not allow students to be their authentic selves through their ePortfolios.

Digital or Tech literacy: Individuals with limited prior exposure to technology and digital platforms might find it challenging to navigate the use of ePortfolios.

Sen’s (1992) central argument is that there are possibilities of variations in outcome even if equal resources are provided and the seriousness of barriers and constraints to achievement is ignored. This study highlights the visible variations of people, such as age, gender, physical disabilities, cognitive ability, language and culture, learning styles, and tech or digital literacies.

That can lead to variations in the achievement of functioning for the effective use of ePortfolios if these variations are going to be ignored. Capability sets suggest that even if students are provided with access to ePortfolio systems as a resource, not all might be equally capable of turning that access into real, meaningful achievements.

Therefore, it is crucial to consider the above-mentioned personal diversities of people, especially students and teachers, in terms of their external and internal (personal) characteristics when considering the use of ePortfolios. The capability approach affords opportunity through its theory of conversions (Sen, 2001).

Challenges and obstacles for ePortfolios via Capability Set: Particular needs, interests, and desires at a particular time

The difference in focus is particularly important because of extensive human diversity (Sen, 1992). Two people can have the same primary resources, but their needs and desires may differ at a particular time. For example, a disabled person cannot function in the way an able-bodied person can, even if both have the same income. As such, people’s priorities and motivations change over time and are influenced by personal growth, socio-economic context, or career shift, and this can also pose challenges and obstacles for the effective use of ePortfolios.

Motivation at a particular time: Some people may not see the relevance or benefit of an ePortfolio if it is regarded as an administrative task rather than a personal development and growth tool.

Evolving personal goals: The ePortfolio may not be necessary for a shifting career goal or interest, which can be assumed to be irrelevant.

Privacy and ownership concerns: People may be hesitant to fully express themselves if they fear that the portfolio might be used for surveillance, assessment, or judgment rather than self-development.

Challenges and obstacles for ePortfolios via Capability Set: Freedoms

Freedoms for the effective use of ePortfolios emerged as significant in this study. The capability approach emphasises the importance of freedoms and unfreedoms (Sen, 2001) to people with the use of ePortfolios. Freedoms in terms of the CA are those real opportunities or choices available to people based on their specific circumstances, including their ability to choose different life paths that influence his/her ability to achieve certain objectives. Conversely, unfreedoms are those circumstances that hinder such abilities and efforts to achieve and may vary from person to person, as well as between spaces (Munje & Maarman, 2016).

Time constraints: People, including students and professionals with caregiving responsibilities, part-time jobs, and health conditions, may lack the time or energy to use or maintain ePortfolios.

Contextual irrelevance: ePortfolios may be designed without considering diverse needs of people, for example, alternative pathways to learning, informal or experiential learning, and project-based learning, which can limit the value for some people who may want to use ePortfolios.

Standardisation pressure: Another challenge or obstacle for people who may want to use ePortfolios is the imposed rigid templates by some institutions or the expectations that don’t accommodate individual expression or developmental stages, limiting the freedom of use of ePortfolios.

Dlamini (2022) contends that inequality is morally unjustified, as it limits people’s freedom of full participation in the development of their social and cultural capital. The above-mentioned obstacles can limit the freedom to use ePortfolios as genuine self-expression and personal development, as alluded to by McAlpine (2005). The effective use of ePortfolios should be approached with a critical understanding of the socio-economic and cultural context in which people operate. By ignoring the underlying issues of spatial inequalities, cultural marginalisation and threats to personal freedoms, ePortfolios risk of becoming instruments that reinforce existing disparities rather than tools for inclusive and equitable education.

ADDRESSING THE OBSTACLES TO THE EFFECTIVE USE OF EPORTFOLIOS

The education sector had a rude awakening with the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, forcing institutions of learning to embrace digital technology for sustainable approaches and integrate it into assessment. In addition, student profiles have evolved substantially in the twenty-first century around the globe (Plüddeman et al., 2025). For the education system to be prepared for twenty-first-century students, it is important to give attention to training and evaluation that accommodate a holistic approach; as such, restructuring evaluation tools should be prioritised and ePortfolios are a fundamental pathway (Ndebele et al., 2024).

The effective use of ePortfolios aligns with the Capability approach of Sen (1992, 1999, 2001) as it considers a range of factors that should be addressed to cater for the evolving characteristics of a twenty-first-century child. We emphasise that the solution should be holistic, inclusive, and flexible to accommodate the learning needs of all learners.

The table below proposes solutions to the obstacles highlighted in Figure 1 through the lens of the capability sets.

Table 1

Solutions to the obstacles for the effective use of ePortfolios (created by Authors)

|

Capability sets |

Solutions |

||

|

Spatial inequalities |

Offline access

|

Data-free packages should be made available to schools and learners to accommodate the digital requirements of the 4th industrial revolution for all people in all areas, including rural areas. ePortfolios should be designed to function offline, especially in areas where schools have limited connectivity. |

|

|

Building equity in Technology initiatives |

The Department of Education should prioritise quality education in every school and every classroom through equal provision of resources, including technological apparatus and human capital that acquire the relevant skills to enhance digital literacy skills in all schools. |

||

|

Accessibility via mobile devices

|

Consider the effective use of smartphones as it is easily accessible. It can be more cost-effective as computers are not widely used and need infrastructure and human capital to monitor. |

||

|

Build Community hubs |

Schools should collaborate with external parties to build partnerships to fast-track digital literacy development, including libraries, schools, churches, and community centres for physical access points. |

||

|

Personal diversities |

Consider different language options

|

Acknowledge that learners come from different linguistic, cultural, historical, and educational backgrounds. ePortfolios should be tailor-made to cater for the holistic development of the learner, including language accommodations, considering a multilingual approach such as MTTBE and translation tools. |

|

|

Consider different learning styles through multimedia model submissions.

|

Diversify activities to cater to multiple intelligences that suit the needs and individual attributes and characteristics of the learners, including video, audio, text, and images. Digital and tech literacy should be incorporated from preschooling. All schools should have a tech hub to cultivate digital skills in schools. |

||

|

Special features/icons to allow smooth accessibility |

Cater to all forms of learning disabilities and impairments through making provisions for screen readers, adjustments of font sizes and friendly colour contrast, and easy navigation. |

||

|

Particular needs, desires, and interests at a particular time |

Consider individual needs |

We must be conscious that learners need accommodations for various learning disabilities, health conditions, and socio-economic challenges. Design individual learning plans that connect ePortfolios to personalised support strategies and accommodations. Effective and sufficient feedback from teachers should be encouraged. Feedback should be ongoing for both formative and summative assessments. |

|

|

Submission flexibility |

Learners should be given asynchronous options to work independently and submit tasks when it suits their schedule, learning ability, and capability, based on suitable concessions that speak to individualised support plans. Encourage regular reflections and updates. Create longitudinal views for growth and changing aspirations. Allow integration across subjects, including informal learning initiatives, hobbies, and extracurricular activities for broader, holistic development. |

||

|

Track goals and progress |

The ePortfolio structure and layout should include features that track goals and progress. Ensure that the ePortfolio is relevant and serves the intended purpose. |

||

|

Freedoms |

Encourage learner autonomy |

Create a safe space where learners feel comfortable taking ownership and agency for their learning. Learners must have a variety of options to organise their ePortfolio and who can gain access to it. |

|

|

Privacy rights must be considered carefully |

Access to ePortfolios should be guided and controlled by consent. A trusted individual should monitor privacy levels of each component of the learner’s ePortfolio, who can be a teacher, school psychologist, or parent. If the learner is age-appropriate, the institution can allow learners to have control over their data and set privacy levels. |

||

|

Provide a re-workable, structured template |

ePortfolios should not follow a learner structure. The school should use a structured template to guide the use of ePortfolios for key components but should not limit creativity; personalised options should be readily available. Learners are exposed to a variety of options, such as personal storytelling, that reflect unique learning journeys. |

||

The implementation of ePortfolios seems to be a promising avenue that acknowledges the holistic development of the learners as well as the linguistic and cultural diversity. ePortfolios are a tool that merges all elements of the performance of the individual learner, which in essence can respond to the individual learner’s learning needs. The inclusion of ePortfolios encourages social justice, as it provides learners with opportunities to increase academic achievement and, in turn, could lead to opportunities for higher education learning and job opportunities.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The chapter emphasises the need for transformative change within the education system, as current practices perpetuate social injustices, constraining learners in their respective learning contexts. ePortfolios can be acknowledged as a bridge to overcome learning barriers and signify a potential solution to create a more inclusive educational environment to enhance the capabilities of students. ePortfolios are a promising avenue that encompasses the holistic development of learners, putting their strengths and abilities at the centre. By considering the implementation of ePortfolios in the schooling context, we will narrow the gap of social exclusion based on learning barriers and linguistic and cultural differences. We accentuate that ePortfolios are linguistically and culturally responsive and are the fundamental tool that could cater to a variety of learning styles.

CONCLUSION

The focus of this chapter highlights the essence of ePortfolios from a holistic point of view. Reconsidering alternative ways to accommodate twenty-first-century learners underscores the effective use of ePortfolios that will deeply consider equity, inclusion, and empowerment. The chapter closely examines social justice in relation to fair distribution of resources and equal access to skills development that is yet to level the playing field in practice. If one truly wants to address the obstacles of social inequality, personal diversity, particular needs, desires, interests at a particular time, and freedoms, it is imperative to note that ePortfolios can be a powerful tool for supporting learners’ holistic development and academic achievements, which will expand their real-life opportunities in educational contexts and beyond. The chapter aligns with the constituents of the Capability approach as it aims to address inequality and equity issues within schools that host a variety of students with diverse learning abilities and linguistic, cultural, and historical backgrounds.

REFERENCES

Aboulsoud, S.H. (2011). Formative versus summative assessment. Education for Health, 24(2), 651.

Alexander, J.M. (2016). Capabilities and social justice: The political philosophy of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Capabilities-and-Social-Justice-The-Political-Philosophy-of-Amartya-Sen-and-Martha-Nussbaum/Alexander/p/book/9781138257306?srsltid=AfmBOor0CIsQvd_88Qgaux0ElNYxtE6Os0MB_zbAXC429zgQm-nqzmuz

August, C. (2023). Exploring translingual assessment for learning in multilingual grade 10 Afrikaans home language classes. (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa). UWC Scholar. https://uwcscholar.uwc.ac.za/items/4786b7ef-da43-41d6-b6ce-768ed21362bf

Bisai, S., & Singh, S. (2018). Rethinking Assessment-A Multilingual Perspective. Language in India, 18(4), 308-319.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324770714_Samrat_Bisai_and_Smriti_Singh_Rethinking_Assessment-A_Multilingual_Perspective_308_Language_in_India_wwwlanguageinindia

Borthwich, H.M. (2021). Curated carefully: Shifting pedagogies through ePortfolio use in elementary classrooms. (Doctoral dissertation, The University of British Columbia, Canada). UBC Library Open Collections. https://open.library.ubc.ca/media/stream/pdf/24/1.0401970/4

Browne, E. (2016). Evidence on formative classroom assessment for learning. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b76acef40f0b64350cbf7f8/003_Classro om_Assessments_v3.pdf.

Cambridge Assessment International Education. (2019). Assessment for learning. https://www.cambridgeinternational.org/Images/271179-assessment-for-learning.pdf

Department of Basic Education. (2011). National Protocol for Assessment Grades R – 12. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Policies/NatProtAssess.pdf

Dlamini, R. S. (2022). Complex Inequalities and Inequities in Education: Expanding Socially Just Teaching and Learning through Digitalisation in South Africa. Alternation Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa, 39(1), 193-213. DOI:10.29086/2519-5476/2022/sp39a9

Hoffman, S., & Maarman, R. (2024). Teachers’ voices and quality education in the basic education discourse in South Africa. Perspectives in Education, 42(4), 333-348. DOI: https://doi.org/10.38140/pie.v42i4.8048

Hoffman, S.M. (2017). Capability sets of teachers with regards to the implementation of the curriculum and policy statement in a no-fee school community in the Western Cape. (Master’s thesis, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa). UWC Scholar. https://uwcscholar.uwc.ac.za:8443/server/api/core/bitstreams/0ff296eb-4a78-40f6-b320-13d8c47989c8/content

Johnston, P., & Costello, P. (2005). Principles for Literacy Assessment. Reading Research Quarterly, 40, 256-267. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.40.2.6

Jordan, B., & Putz, P. (2004). Assessment as practice: Notes on measures, tests, and targets. Human Organization, 63, 346–358. DOI:10.17730/humo.63.3.yj2w5y9tmblc422k

Kok, I. & Blignaut, S. 2009. Introducing developing teacher- students in a developing context to ePortfolios. [Paper]. North-West University.

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/INTRODUCING-DEVELOPING-TEACHER-STUDENTS-IN-A-TO-Kok-Blignaut/ad7afa1c16b5c8950d353233ae3584c736a0298a

Makoelle, T. (2009). Outcomes-Based Education as a Curriculum for Change: A Critical Analysis. In H. Piper, J. Piper & S. Mahlomaholo (Eds), Educational research and transformation in South Africa (pp. 71-80). Potchefstroom: Platinum Press.

Marshall, B. (2017). The politics of testing. English in Education, 51(1), 27-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/eie.12110

McAlpine, M. (2005). ePortfolios and Digital Identity: Some Issues for Discussion. E-Learning and Digital Media, 2(4), 378-387. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2005.2.4.378

Moss, P.A. (2008). Sociocultural implications for the practice of assessment I: Classroom assessment. In P.A. Moss, D. Pullin, J.P. Gee, E.H. Haertel, & L.J. Young (Eds.), Assessment, equity, and opportunity to learn (pp. 76-108). Cambridge University Press: New York.

Munje, P., & Maarman, R. (2016). A capability analysis on the implementation of the school progression policy and its impact on learner performance. Journal of Education, 66, 185 206. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i66a07

Ndebele, C., Marongwe, N., Ncanywa, T., Matope, S., Ginyigazi, Z., Chisango, G., … & Garidzirai, R. (2024). Reconceptualising initial teacher education in South Africa: A quest for transformative and sustainable alternatives. Interdisciplinary Journal of Education Research, 6, 1-19. DOI:10.38140/ijer-2024.vol6.07

Noakes, T. (2018). Inequality in digital personas – ePortfolio curricula, cultural repertoires and social media. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town). OpenUCT. https://open.uct.ac.za/items/e93af306-4061-4df3-b916-35670cfd3d98

Pallitt, N., Strydom, S. & Ivala, E. 2015. CILT Position Paper: ePortfolios. CILT, University of Cape Town. http://hdl.handle.net/11427/14039

Plüddemann, P., Cutalele-Maqhude, P., Sheik, A., & Chetty, R. (2025). Language, literacy and STEAME education. In R. Govender, J. de Beer, R. Maarman & R. Chetty (Eds), Future-proofing STEAME education in South Africa (pp.93-109). Aosis

Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment Literacy for Teachers: Faddish or Fundamental? Theory Into Practice, 48, 4-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802577536

Robeyns, I. (2011). The capability approach. In: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/capability-approach/

Ruiz-Primo, M.A. (2011). Informal formative assessment: The role of instructional dialogues in assessing students’ learning. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1), 15-24. DOI:10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.04.003

Schissel, J.L., De Korne, H., & López-Gopar, M. (2018). Grappling with translanguaging for teaching and assessment in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts: Teacher perspectives from Oaxaca, Mexico. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(19), 1-17. DOI:10.1080/13670050.2018.1463965

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Random House.

https://kuangaliablog.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/amartya_kumar_sen_development_as_freedombookfi.pdf

Sen, A. (2001). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

https://oxford.co.za/shop/higher-education/economics-higher-education/9780192893307-development-as-freedom/

Sen, A. 1992. Inequality re-examined. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/2940919

Shohamy, E. (2011). Assessing multilingual competencies: Adopting construct valid assessment policies. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 418-429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01210.x

Taras, Maddalena. (2008). Summative and Formative Assessment: Perceptions and Realities. Active Learning in Higher Education, 9, 172-192. 10.1177/1469787408091655.

AUTHORS

Dr. Chantelle August-Mowers is an academic, researcher and lecturer. She is the Head of Foundation Phase and Intermediate Phase Programs at Two Oceans Graduate Institute. She holds a PHD in Language and Literacy. Her research interest includes (but not limited to) multilingualism, with specific reference to mother tongue language, translanguaging and inclusive assessment practices. Her passion for language studies is driven by underpinning social justice imperatives and believe that mother tongue language is a fundamental human right. Grounded in the Ubuntu Philosophy, August-Mowers believes that every student should be treated fairly and respected irrespective of their diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. In doing so, every student should have quality education and equal opportunities. She believes, Education is the

fundamental pathway to inclusive, linguistic and cultural responsiveness.

Email: chantyaugust@gmail.com

Dr. Samantha Hoffman, is an academic and Field Specialist Leader for Social Sciences and Languages in the BEd Intermediate Phase and PGCE Programme at Two Oceans Graduate Institute. She holds a PhD in Education and her research interest centres around the discourse of Quality Education involving interdisciplinary research to impact teacher education and basic education through the lens of the Capability approach and the Ubuntu Philosophy.

Email: samanthahoffman247@gmail.com