25 A framework for developing ePortfolios to enhance teacher training beyond COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities

Benkosi Madlela

University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Electronic portfolios (ePortfolios) are an essential component of teacher training that provides student teachers with opportunities to reflect on the development of their teaching philosophy and put it into practice. Technological advancement in the 21st century has presented several innovative opportunities like eportfolios that enhance teacher training programmes and achievement of intended outcomes. They allow student teachers during teaching practice to document and reflect on their work. EPortfolios assisted higher education institutions to navigate through challenges caused by COVID-19 pandemic. They still remain relevant post COVID-19 pandemic as higher education institutions continue to position themselves in the 4th industrial revolution. The chapter explored challenges and opportunities of using ePortfolios in teacher training programmes and suggested a framework for effective development of ePortfolios. Data was gathered from fifty secondary sources in SCOPUS and Web of Science databases. Data analysis revealed that implementation of ePortfolios in higher education institutions faces challenges such as workload and time issues, costs of computers and internet, and technical complications. Despite these challenges, ePortfolios promote productive learning and information literacy, enable critical thinking, facilitate a learner-centred approach that stimulates learners’ desire to learn, and allows learners to share ideas and experiences through a collaborative approach. It is recommended that institutions of higher education should train lecturers and students on ePortfolio software and tools, modernise their ICT infrastructure (software and hardware), establish technological support structures for learners, promote learner collaboration during ePortfolio preparation, and adopt community of practice and community of inquiry frameworks for effective ePortfolio development.

Keywords: ePortfolios, COVID-19, productive learning, framework, teacher training, Reflective Practice, 4th Industrial Revolution

INTRODUCTION

The word “portfolio’s” etymology has its origins in the Italian word portafoglio. This was a case or folder for carrying loose papers or pictures. “Porta” means “to carry,” and “folio” means “loose sheet of paper” (Lam, 2018, Dorn, Sabol & Maoriginsindeja, 2013). In the context of art, portfolios were a means of showcasing a selection of an artist’s best work curated for a particular audience (Farrell, 2020). Farrell proceeds to assert that over time the meaning of “portfolio” evolved from its origins as a case for holding loose papers for use in other contexts such as government and finance, and during the early 1970s it crossed over to higher education. Farrell (2018) argues that the introduction of portfolios in higher education was influenced by a number of drivers, such as new research and theories of learning, increased focus on quality assurance, and a move away from standardised testing.

Ciesielkiewicz (2019) says that before education was transformed by the digital revolution, a physical portfolio was used by many educators to create collections of student output for specific purposes, such as assessment or the documentation of capabilities. To comply with the prescripts of the Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ), teacher education institutions in South Africa must send student teachers for work-integrated learning (WIL) as part of practical learning (Mollo, Thabane & Lenong, 2022). It is during Teaching Practice (TP) when students are required to prepare a portfolio of evidence to demonstrate that they have acquired major pedagogical skills in classroom management, organisation, self-criticism, leadership, teaching, testing, and assessing (Mollo et al., 2022).

Sithole (2011) notes that in the University of Botswana’s Faculty of Education, portfolio assessment of teaching practice was first introduced in May 2010. In line with this assertion, Farrell (2020) reveals that from 2010 to 2020, a shift towards an emphasis on pedagogy and the student learning experience occurred in ePortfolio research and practice. The teaching practice ePortfolio is specifically aimed at enhancing the teaching practice as a source of reflection and learning. It is further aimed at assisting student teachers to reflect on their own performance and their future as educators and to enable them to observe diverse aspects of the school reality (Mollo et al., 2022). In 2013, when the University of South Africa (UNISA) officially adopted the e-learning mode of delivery, it also introduced ePortfolios in some modules (Letseka, Letseka & Pitsoe, 2018, and Mbatha, 2013). UNISA’s transition from Open Distance Learning (ODL) to Open Distance and Electronic Learning (ODeL) brought new teaching approaches. Ngubane-Mokiwa (2017). Dunbar-Hall, Rowley, Brooks, Cotton, and Lill (2015), however, argue that ePortfolios in higher education were introduced in the 1990s, earlier than 2010, to replace paper-based portfolios.

The introduction of ePortfolios marked a migration from physical, paper-based portfolios to an electronic format. Ciesielkiewicz (2019) argues that once digital capabilities became more commonplace, the ePortfolio eclipsed its physical counterpart. It is now the platform that students can use to compile, organise, and formulate a digital presentation across various types of media. Though Cahill, Nelson, Strawhecker, and Vu (2022) argue that ePortfolios are increasingly being used in the field of teacher education. Mollo et al. (2022) reveal that at the Central University of Technology (CUT), the teaching practice portfolio has always been paper-based. CUT introduced ePortfolios because it did not have storage space for paper portfolios. The Department of Higher Education and Training required that portfolios should be kept for three years after the student had completed studies. Another reason was the COVID-19 pandemic, which restricted the physical presence of students and lecturers on campuses. This shows that CUT did not proactively introduce portfolios, but it reactively introduced them to mitigate challenges that it faced. Puleng Modise and Vaughan (2024) reveal that COVID-19 forced many higher education institutions to move their teaching to online space, and this has made ePortfolios become more relevant since they are web-based. The introduction of ePortfolios in a reactive manner due to COVID-19 carried the risk of lack of readiness, especially pertaining to required infrastructure and ways of supporting learners, especially those from disadvantaged communities.

Modise (2021) notes that though ePortfolios have been used for decades in education, they are still a new trend in some developing countries as they continue to adopt e-learning practices. The study explored opportunities and challenges that are associated with the implementation of ePortfolios in teacher training programmes. An analysis of secondary data helped to recommend strategies and a framework for the effective use of ePortfolios in teacher training programmes. Modise (2021) argues that despite the chosen technology to deliver education, it is necessary to design support strategies that will ensure student success in attaining intended academic standards. The chapter begins by conceptualising ePortfolios and proceeds to discuss benefits and challenges of using ePortfolios in teacher training programmes. At the end a framework for effective use of ePortfolios was presented, followed by conclusions and recommendations.

Research Methodology

Data was gathered from secondary sources such as journal articles, theses, and dissertations from databases such as SCOPUS and Web of Science. Li, Rollins and Yan (2018) argue that Clarivate Analytics’s Web of Science is the world’s leading scientific citation search and analytical information platform. It can be argued that rich information was extracted from Web of Science database complemented by SCOPUS database. Fifty sources that had relevant information for the study were analysed (Kitchenham, Budgen, & Brereton, 2015).

ePortfolios Conceptualised

Jimoyiannis (2013) asserts that an ePortfolio is a dynamic space created by a learner, a group of learners, a community, or an institution in the context of a particular formal or informal educational initiative. It is an organised, aggregated, and purposeful collection of digital artifacts on the Web, for example, content material, ideas, evidence, reflections, and feedback, which are compilations of personal and professional work for documenting abilities, skills, learning, growth, and development. Jimoyiannis further states that an ePortfolio includes demonstrations, resources, accomplishments, articulated experiences, peer and collaborative feedback, and assessment tools, which structure and display an overall view of the participants’ knowledge, skills, interests, learning achievements, and outcomes.

In Walland and Shaw’s (2022) view, an academic ePortfolio is a digital collection of a student’s course-related work that documents learning. It may include essays, photographs, videos, and artwork. It may also capture other aspects of a student’s life, such as volunteer experiences, employment history, and extracurricular activities. Beckers, Dolmans, and Merrienboer (2016) argue that ePortfolios have been defined as integrated electronic compilations of multimodal artifacts that serve as learning evidence, supporting teaching, learning, assessment, and showcasing, focusing on skills development through self-regulation, self-reflection, and self-evaluation. In teacher education during Teaching Practice (TP), student teachers can compile ePortfolios detailing and reflecting on their experiences. ePortfolios would provide them with a versatile platform to showcase their varied and personalised forms of work and reflections (Dave & Mitchell 2014).

Benefits of ePortfolios in Teacher Training Programmes

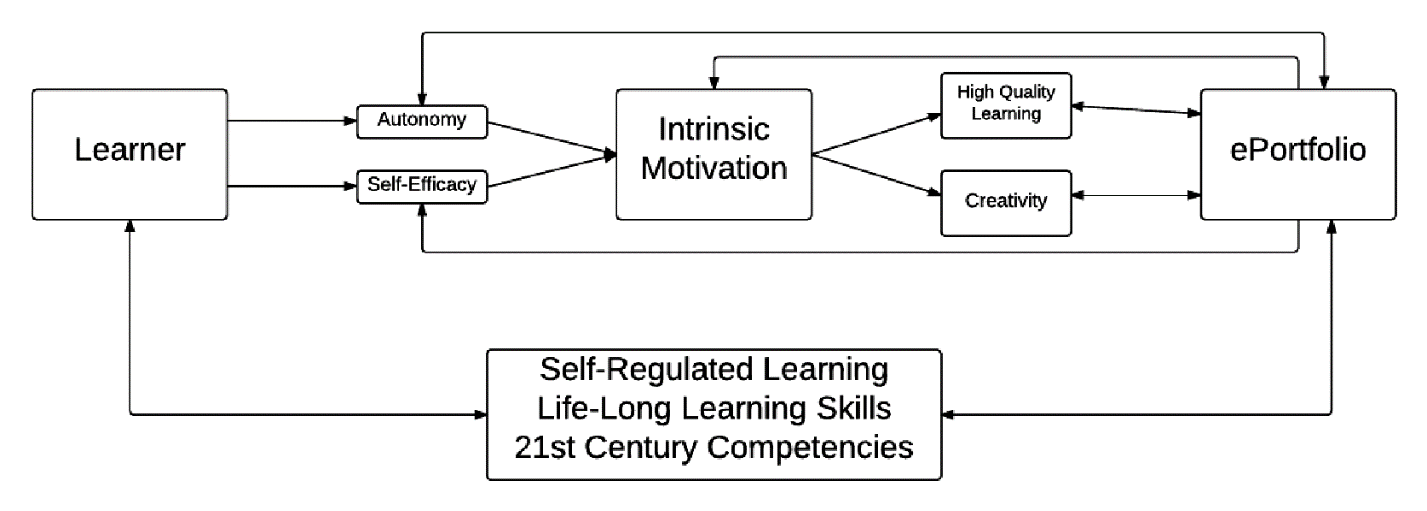

Schutz-Pitan, Seidl, and Hense (2020) say that although ePortfolios are rarely found at German universities, they offer a lot of benefits to lecturers and students. Miller and Morgaine (2009) argue that a well-executed ePortfolio programme is an incredible tool for higher education that promotes deeper learning needed for students. Mei (2022) asserts that research conducted at Northwest University in China about students’ experiences with ePortfolios revealed that ePortfolios promote productive learning and information literacy, enable critical thinking, and stimulate students’ desire to learn. Eighty-five percent of participants in Bolliger and Shepherd’s (2010) study agreed that the ePortfolio actually increased their desire to learn. Mapundu and Musara (2019) state that a study conducted at a private university in South Africa revealed that ePortfolios develop students’ creativity, innovation, self-analysis, and communication skills. For these skills to be fully developed, students should be actively engaged in creating their ePortfolios so that they become autonomous and self-regulated learners (Ciesielkiewicz, 2019). Figure 1 below illustrates how ePortfolios enable learners to develop self-regulated learning skills.

Figure 1

Developing self-regulated learning skills through the ePortfolio

Figure 1 demonstrates that self-regulated learning promoted by ePortfolios motivates learners and equips them with 21st-century competencies such as creativity and lifelong learning skills. Welsh (2012) found that students who used ePortfolios demonstrated an increased development of metacognitive skills, motivation, and self-esteem as compared to the control group that did not use ePortfolios. The experimental group’s summative evaluations were higher than the control groups.

Miller and Morgaine (2009) argue that portfolios enable students to collect their work, reflect on strengths and weaknesses, and strive to improve. This is supported by Sharifi, Soleimani, and Jafarigohar (2016), who argue that in their study, over 85% of respondents indicated that using the ePortfolio was of benefit, noting that it helped with self-assessment and enabled them to examine their growth and to become aware of their strengths and weaknesses. In teaching practice it is essential for student teachers to reflect on their instructional methods and how they relate with learners so that they can improve for the benefit of learners. During TP, student teachers are also supposed to collaborate with their peers and share experiences and ideas. Chisango (2024) notes that group ePortfolios afford learners an opportunity to collaborate and communicate. This promotes the learner-centred approach to teaching and learning. It also builds student relationships, making it possible to share technological skills and resources that are needed in developing ePortfolios. Through collaborations learners can give their peers constructive feedback on their work. This fosters a sense of community and shared learning and growth.

ePortfolios can be accessed by students from anywhere, at any time, using a variety of devices like computers, tablets, and smartphones. The inclusion of social media components in ePortfolio platforms improves their accessibility to learners (Oh, Chan, & Kim, 2020). Ngakane and Madlela (2022) encourage institutions of higher education to use social media platforms such as WhatsApp for learning, because most students are already using these platforms and the majority of them possess mobile phones. The use of different electronic gadgets and social media platforms to share ideas and feedback improves learners’ communication skills and computer literacy. Almost all students who took part in Cheng’s (2022) study indicated that they felt empowered when they designed their Web spaces for ePortfolios. They said that they developed digital literacy skills, and they were impressed by the features on Wix, which prompted them to incorporate text, images, music, pictures, videos, and comment boxes.

In Alharbi’s (2023) study, almost all of the participants reported that preparing ePortfolios positively impacted their design skills, time management and organisational skills, and research skills. They stated that they were presented with an opportunity to solve technical issues, look for solutions, navigate content, pick the right technology, and learn new technical skills. Participants developed their ePortfolios from scratch, created web pages, and added different types of digital content (Alharbi, 2023). These hands-on experiences equip students with diverse skills compared to summative, venue-based examinations.

Challenges of ePortfolios

Ghany and Alzouebi (2019) assert that despite ePortfolios being used by the majority of participants to process documentation, 163 teachers in their study discussed possible drawbacks of their use. It is therefore essential to discuss the challenges that should be taken into consideration when adopting ePortfolios. Some of the major challenges are technical challenges, workload and time issues, and usability of technology (Ghany &Alzouebi, 2019; Cheng, 2022; Alharbi, 2023; and Totter & Wyss, 2019).

ePortfolios require the use of technological gadgets and software. Ghany and Alzouebi (2019) view a lack of technological skills and competencies as a challenge in the implementation of ePortfolios. Some lecturers and students, especially those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds, are not proficient in operating technological systems. Tyroller, Walter, Riess, and Altieri (2023) and Alharbi (2023) state that at the beginning students found it difficult to design ePortfolios since it was their first time to do so. Although the instructor provided the students with supporting materials on how to use different design websites, many students noted the need for further support in terms of choosing the right website for designing the ePortfolio and the need for training. In Cheng’s (2022) study, students reported technological difficulties during the implementation of Wix-based ePortfolio. Most challenges revolved around unfamiliarity with Wix features regarding how to get the post published or how to add a comment box below the journal post. Students also faced editing and typesetting challenges.

Ghany and Alzouebi (2019) argue that it is time-consuming to document teachers’ work and design the portfolio. Participants in Alharbi’s (2023) study reported that the workload was high and it was time-consuming, especially as they needed to keep adding elements and artifacts and writing up their reflections in the ePortfolios for the whole year. Participants who worked full-time noted that work and family requirements and adding achievements to the ePortfolio in a certain format were taking a lot of time. Cheng (2022) notes that learning how to use functions to achieve standard effects and editing processes is time-consuming, and they require a lot of effort. Alharbi (2023) says that participants stated that they faced challenges when it came to writing the reflection piece for the ePortfolio. They argued that writing reflections required them to dig deeper into the learning and make connections between topics. This needed mental effort and consumed more time. Ghany and Alzouebi (2019) believe that it is better to use this time for teaching or preparing student-learning activities.

Tyroller, Walter, Riess, and Altieri (2023) assert that the use of technology presents challenges to some learners. Learners require a lot of effort to come to terms with the new tools and usability of ePortfolio software. Totter and Wyss (2019) argue that in their study all students perceived the software Mahara as too complex. It had a number of confusing features and settings. This made the software a complicated system for learners to work with. In addition to software complications, ePortfolio gadgets are costly. Ghany and Alzouebi (2019) state that computers, the internet, maintenance, upkeep, and upgrading are costly. Learners who come from remote areas without internet and those who come from poor backgrounds might find using technology to prepare ePortfolios very difficult.

A FRAMEWORK FOR THE EFFECTIVE USE OF EPORTFOLIOS

Since the use of ePortfolios in teacher education programmes has both benefits and challenges, it is essential to generate strategies that would mitigate challenges and promote effective use of ePortfolios. The chapter achieved this by adopting a Community of Practice (CoP) framework and a Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework. These were considered appropriate for the chapter because Zhang and Tur (2023) argue that though ePortfolio use is commonly regarded as an individual and self-regulated learning approach, collaboration in the implementation process is essential. Collaboration is regarded as one of the most fundamental processes in ePortfolio construction. Effective collaboration in ePortfolio practice can maximise its advantages, facilitate teaching and learning, and optimise students’ knowledge construction (Tur & Urbina, 2016, and Zhang & Tur, 2022).

Community of Practice (CoP)

Communities of practice are formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning in a shared domain of human endeavor. Examples include a tribe learning to survive, a band of artists seeking new forms of expression, a group of engineers working on similar problems, a group of learners defining their identity at school, a network of surgeons exploring novel techniques, and a gathering of first-time managers helping each other to cope (Wenger, Wenger-Trayner, Reid, and Bruderlein, 2023). Grunspan, Holt, and Keenan (2021) argue that scholars in the field of higher education are focusing on the concept of CoP to adapt to the shifting educational environment caused by COVID-19. A CoP is a group of individuals who share similar concerns and are interested in or enthusiastic about what they are doing and learn how to do it better by frequently interacting (Wenger, 2010). Students and lecturers share similar interests in the development of ePortfolios. To succeed, they need to frequently interact. Wenger (2010) highlights essential elements of CoP as domain, community, and practice.

Domain

Wenger (2010) and Wenger et al. (2023) assert that a domain pertains to people in a community who share an area of interest, expertise, and commitment that members identify with and care about. The first thing to consider is the area of capability that brings the community together, gives it its identity, and defines the key issues that members address together. This shared domain gives everyone a place to start, encourages them to get involved, helps them learn, and gives their activities value. In the context of ePortfolio use, Zhang and Tur (2023) argue that the CoP’s goal is to give students and educators a way to collaborate, interact, share best practices, and improve in using ePortfolios in the classroom or in the institution.

Community

The ability of a community of practice to make progress depends on the composition of the group of people who need to be involved. In the community, individuals talk to each other, try to solve problems, share information, and make new connections. Community as a concept generates the social fabric necessary for collective learning. A strong community stimulates interaction and encourages the sharing of ideas (Wenger 2010 and Wenger et al., 2023). The complexities associated with the development of ePortfolios require a collective approach. Students and lecturers need to work as a team and share ideas, as advocated by Lev Vygotsky’s social constructivist learning theory, which believes that students learn better through collaborating and interacting with each other and adults like teachers at school (Akpan, Igwe, Mpamah, & Okoro, 2020).

Practice

Wenger (2010) says that the practice is the particular emphasis around which the community creates, distributes, and maintains its core of collective knowledge, while the domain represents the community’s broad area of interest. In this sense, practising together to learn from one another, whether face-to-face or remotely in a small or big group, might be regarded as an additional foundation of CoP. Wenger et al. (2023) argue that members of the group can learn with each other by combining their collective wisdom to understand a challenge or devise an innovative solution.

According to Wenger et al. (2023), over time, when the three aspects are well aligned, a community of practice can make a big difference to members’ ability to accomplish what they want individually and collectively. Learning in a community of practice is not merely the transfer or sharing of knowledge from someone who knows to someone who doesn’t know, but it is an ongoing cycle by which community members generate ideas that they try in practice. They learn further by reflecting on how well their ideas worked or did not work. The stories they tell each other about how they tried something out and what happened as a result are a key learning resource for other members of the community. In social constructivism, learning occurs through learner interaction and sharing of ideas (Akpan et al., 2020). If the CoP framework is adopted by higher education institutions in the preparation of ePortfolios, students can collaborate and share ideas, challenges, resources, experiences, and reflections. This would motivate them and enable them to participate productively in the development of their ePortfolios.

Community of Inquiry (CoI)

Garrison (2016) asserts that CoI is a hypothetical framework for creating ideal internet learning environments that stimulate fundamental thinking, inquiries, and conversation among learners and educators. Garrison (2007) views CoI as a collaborative constructivist process model that specifies the critical aspects of a successful online higher education learning experience. It is the process of creating a rich and meaningful learning experience via the development of three presences: social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence. Shea and Bidjerano (2010) updated the CoI and added the learner presence as the fourth presence.

Social Presence

Social presence is the participants’ capacity to connect with the learning community, interact meaningfully in a trustworthy setting, and create interpersonal relationships by projecting their different characteristics. Social presence promotes a collaborative atmosphere for online learning. Learners construct collaboration channels using the capabilities of the existing technology to facilitate effective learning (Garrison, 2007, and Castellanos-Reyes, 2020). Since ePortfolios are prepared using technological gadgets and software, learners can effectively prepare them if they collaborate and share knowledge, ideas, digital expertise and resources. This can benefit all learners, especially those who come from disadvantaged communities that do not have adequate resources and technological infrastructure.

Cognitive Presence

Garrison (2007) argues that cognitive presence entails the ability of ePortfolio users to develop and sustain knowledge via ongoing thinking and collaborative discussion during the ePortfolio practice. This requires the ePortfolio learners to actively reflect and think critically on their work and their peers’ work. Though it is not always the case, critical thinking and collaboration occur naturally. Garrison (2007) proceeds to argue that cognitive presence emphasises that critical thinking is the purpose of all educational endeavours. To successfully prepare the ePortfolio, learners need to think critically and reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of their work.

Teaching Presence

Castellanos-Reyes (2020) asserts that the teaching presence is required to enable and accept managerial functions. In Garrison’s (2007) view, teaching presence is the creation, development, and guidance of cognitive and social processes throughout the implementation of ePortfolios by the teacher. It includes the teachers’ evaluation, feedback, and ongoing support; teacher-facilitated peer collaboration, including peer feedback; and peer assistance throughout the ePortfolio journey. Peer collaboration and peer assistance are essential in constructivism because they enable learners to create their own knowledge and solve encountered problems (Akpan, Igwe, Mpamah, & Okoro, 2020). Since ePortfolio preparation has challenges such as software complications and high costs of ePortfolio gadgets, Totter and Wyss (2019) argue that if learners collaborate, they will assist each other with necessary gadgets and navigation of complicated features of the ePortfolio software. It is therefore essential for lecturers to encourage and promote learner collaborations during ePortfolio preparation. Social media platforms like WhatsApp can be used to foster learner collaboration (Ngakane & Madlela, 2022, and Madlela & Umesh, 2025).

Learner Presence

Shea and Bidjerano (2010) state that learner presence includes aspects such as self-efficacy and behavioural, cognitive, and motivational constructs supportive of online learner self-regulation. It involves active participation, planning, strategic selection of learning evidence, using appropriate technological tools to create ePortfolios, cooperation with others, self-evaluation, and self-reflection. Modise (2021) views the presence of the instructor and learners in an online learning environment in the context of using ePortfolios as essential in higher education practice. Modise says that learner presence is characterised by planning, strategic selection, active engagement, and use of technology to facilitate collaborative learning, self-monitoring, self-assessment, and self-monitoring through reflective practice. The application of the presence constructs is summarised in Table 1 under the participant, content, and tools headings.

Table 1

Community of Inquiry (adapted from Biccard, 2025, p.144)

|

|

Participants

|

Content

|

Tools

|

|

Teaching presence |

Analyse course participants. Refer to demographical background information regarding the participants. Reflect on which aspects of teaching can be devolved to them. |

Find or create content that can provide a teaching presence. Consider the content that students can find/design/produce for the course. |

Harness tools that can provide teaching presence e.g. editing software, etc. Consider the use of a course app that can send reminders and notifications. |

|

Cognitive presence |

Interaction of participants with content, ideas, and concepts. Cognitive equity among course participants must be encouraged and stimulated. |

The content selected or shared during the course sets the tone for the cognitive presence of the course. Resource sharing should be encouraged. |

The technological tools used contribute to the cognitive presence, e.g. the use of referencing software or map software. |

|

Social presence |

Distribution of communication and interaction must be a design feature. Higher order engagement e.g. creating joint artifacts and collaboration must be factored into the course design. |

Provision of interesting, conflicting or authentic content may allow an increased social presence. Students may be motivated by the content to become socially present in the course. Designing a course in which students need to share their own resources and content may increase social presence in the course. |

A decision needs to be made in terms of the type of tools used for communication and interaction e.g. emails, discussion forums, mobile chat apps that can contribute to the social presence of the course. |

|

|

|

|

|

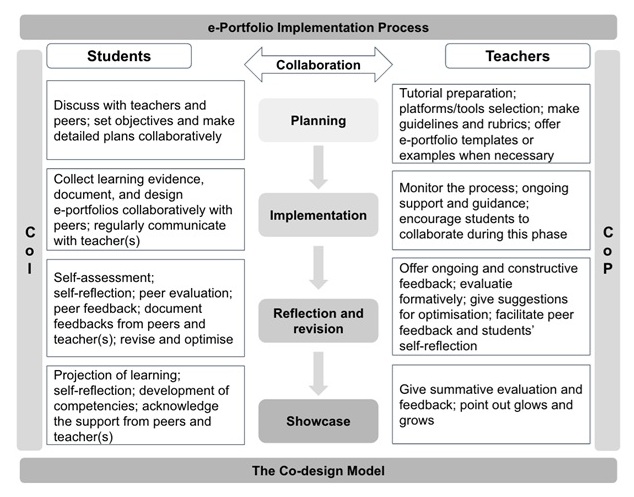

The CoP and CoI frameworks are vital in creating collaborative and engaging learning environments, especially when learners are preparing ePortfolios. These two frameworks can be applied synergistically to promote learning and information sharing during the ePortfolio preparation process. Figure 2 highlights how the CoP and the CoI could be used in synergy in the ePortfolio implementation process.

Figure 2

ePortfolio implementation process

Figure 2 demonstrates how learners and their lecturers/educators can work collaboratively in the ePortfolio implementation under the auspices of the CoP framework and CoI framework right from planning up to showcasing outputs. Zhang and Tur (2023) argue that at the ePortfolio planning phase, teachers, learners, and peers should work together to select objectives, conduct tutorials, select e-platforms, and share guidelines, rubrics, and ePortfolio templates. Doing so would assist learners in knowing what is expected of them and the kind of support that is available during their ePortfolio journey. At the implementation phase, learners collect and document ePortfolio evidence in collaboration with their peers while maintaining constant communication with their educators. Educators give guidance and support to learners and encourage them to collaborate with each other. Madlela and Umesh (2024) encourage educators to use Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) to collect and document information collaboratively with their peers. Since learners stay in different geographic areas, the use of technology is essential. Madlela (2022) asserts that educational institutions, including those in rural areas, should invest in technology that is available in their contexts to bridge time and distance constraints.

Zhang and Tur (2023) assert that at the reflection and revision phase, educators give formative constructive feedback and suggestions and encourage learners to self-reflect and give each other peer feedback. Based on educator feedback and guidance, peer feedback, and self-reflection, learners revise their ePortfolios. This keeps learners busy and actively involved in their learning. Application of constructivism teaching and learning principles Bada and Olusegun (2015) motivate students and give them ownership of what they learn, since learning is based on students’ questions and explorations, and often the students have a hand in designing the assessments.

Constructivism promotes social and communication skills by creating a classroom environment that emphasises collaboration and exchange of ideas. Students learn how to articulate their ideas clearly as well as to collaborate on tasks effectively. At the showcase phase, according to Zhang and Tur (2023), educators give learners summative evaluation and feedback. Learners develop competencies, self-reflect, and acknowledge the support from their peers and educators. ePortfolios could be effectively prepared in institutions of higher education if the CoI and CoP frameworks could be used with the support of a constructivist teaching and learning theory.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

From the analysis of secondary data, it can be concluded that institutions of higher education in South Africa have adopted ePortfolios in teacher training programmes. ePortfolios have proven to have the following benefits: promoting productive learning and information literacy and developing students’ creativity, innovation, self-analysis, collaboration, and communication skills. In constructivism, learner collaboration is essential as it enables learners to share ideas and resources. This makes it possible for learners who have resources to share with those who do not have them. It was also concluded that most institutions of higher education did not proactively introduce ePortfolios. They reactively introduced them during COVID-19 when lecturers and learners could not physically access university campuses. This means that institutions were not yet ready to implement the ePortfolio project. In addition to the challenge of lack of readiness, ePortfolios pose the following challenges: technical challenges, workload and time issues, costs of computers and internet, and usability of technology. It was further concluded that for successful implementation of ePortfolios, educators should simultaneously use the CoP framework and the CoI framework together with the principles of a constructivist teaching and learning theory. As illustrated in Table 1 and Figure 2, the CoP framework and the CoI framework enable educators, learners, and their peers to co-design ePortfolios. This results in the effective development of ePortfolios by learners as they share ideas and resources with each other and also benefit from guidance from educators and feedback from both educators and peers. Co-designing of ePortfolios also makes it possible for educators, learners, and peers to share ideas on how to use electronic gadgets and how to navigate complex features of ePortfolio software and tools.

Based on the analysis of secondary data, the CoP framework, the CoI framework, and principles of a constructivist teaching and learning theory, it was recommended that institutions of higher education offering teacher training programmes should train lecturers and students and equip them with skills and knowledge of using ePortfolio software and tools, modernise their ICT infrastructure both hardware and software, and integrate social media platforms in their Learning Management Systems (LMS) to facilitate learner collaboration during ePortfolio preparation exercises, establish support structures for all students, especially those students who have no access to the internet and technological gadgets like computers, smart phones, and scanners because they come from disadvantaged communities, adopt the CoP framework and the CoI framework together with the constructivist teaching and learning theory to foster a collaborative and co-design approach by lecturers and students and their peers in the development of ePortfolios. This would promote a learner-centered approach and result in effective ePortfolio development by students in higher education teacher training programmes.

REFERENCES

Akpan, V. I., Igwe, U. A., Mpamah, I. B. I., & Okoro, C. O. (2020). Social constructivism: Implications on teaching and learning. British Journal of Education, 8 (8), 49-56.

Alharbi, H. (2023). The Impact and Challenges of the Implementation of a High-Impact ePortfolio Practice on Graduate Students’ Learning Experiences. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(10), 231-246.

Bada, S. O., & Olusegun, S. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66-70.

Beckers, J., Dolmans, D., & Merrienboer, J. V. (2016). ePortfolios enhancing students’ self-directed learning: a systematic review of influencing factors. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2528

Biccard, P. (2025). A distributed perspective to the community-of-inquiry framework for distance education. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 40(2), 136-151.

Bolliger, D. U. & Shepherd, C. E. (2010). Student perceptions of ePortfolio integration in online courses. Distance Education, 31(3), 295-314. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2010.513955

Cahill, A. S., Nelson, R. M, Strawhecker, J., & Vu, P. (2022). School administrators’ perceptions of electronic portfolios and the hiring of K-12 teachers. International Journal of ePortfolio, 12(1), 47–58. https://dgmg81phhvh63.cloudfront.net/content/user-photos/IJEP/Article-PDFs/Vol-12- 1/IJEP378_12-1_47-58.pdf

Castellanos-Reyes, D. (2020). 20 years of the community of inquiry framework. TechTrends, 64, 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00491-7

Cheng, Y. H. (2022). ePortfolios in EFL writing: Benefits and challenges. Language Education & Assessment, 5(1), 52-69. https://doi.org/10.29140/lea.v5n.815

Chisango, G. (2024). Exploring the effectiveness of ePortfolios in a first-year undergraduate Project Management course. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South, 8(3), 25-43.

Ciesielkiewicz, M. (2019). The use of ePortfolios in higher education: From the students’ perspective. Issues in Educational Research, 29(3), 649-667. http://www.iier.org.au/iier29/ciesielkiewicz.pdf

Dave, K., & Mitchell, K. (2024). Enhancing flexible assessment through ePortfolios: A scholarly examination. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.53761/wearsf41

Dorn, CM, Sabol, S.S and Madeja, F. (2013). Assessing expressive learning. London: Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410608970

Dunbar-Hall, P., Rowley, J., Brooks, W., Cotton, H., & Lill, A. (2015). ePortfolios in music and other performing arts education: History through a critique of Literature. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, (36)2, 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/153660061503600205

Farrell, O. (2020). From portafoglio to eportfolio: The evolution of portfolio in higher education. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1).

Farrell, O. (2018). Failure to launch: The unfulfilled promise of eportfolios in Irish higher education: An opinion piece. DBS Business Review, 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22375/dbr.v2i0.30

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Online Learning, 11(1), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v11i1.1737

Garrison, D. R. (2016). E-learning in the 21st century: A community of inquiry framework for research and practice. Routledge.

Ghany, S. A., & Alzouebi, K. (2019). Exploring teacher perceptions of using ePortfolios in public schools in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 7(4), 180-191.http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.7n.4p.180

Grunspan, D. Z., Holt, E. A., & Keenan, S. M. (2021). Instructional communities of practice during COVID-19: Social networks and their implications for resilience. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v22i1.2505

Jimoyiannis, A. (2013). Developing a pedagogical framework for the design and the implementation of ePortfolios in educational practice. Themes in Science and Technology Education, 5(1-2), 107-132.

Kitchenham, B. A., Budgen, D., & Brereton, P. (2015). Evidence-based software engineering and systematic reviews. CRC press.

Lam, R. (2018). Background of portfolio assessment. In: Portfolio Assessment for the Teaching and Learning of Writing. Singapore: Springer Briefs in Education. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1174-1_1

Letseka, M., Letseka, M. M., & Pitsoe, V. (2018). The challenges of e-Learning in South Africa. Trends in elearning, 121-138.

Li, K., Rollins, J., & Yan, E. (2018). Web of Science use in published research and review papers 1997–2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Scientometrics, 115(1), 1-20.

Madlela, B. (2022). Exploring educational technologies used by Mthwakazi University rural satellite campuses to implement distance teacher education programmes. Interdisciplinary Journal of Education Research, 4, 75-86. https://doi.org/10.51986/ijer-2022.vol4.06

Madlela, B. & Umesh, R. (2025). Utilisation of social media to support inquiry-based learning in science. International Journal of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, 5(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.53378/ijstem.353155

Mapundu, M. & Musara, M. 2019. E‐portfolios as a tool to enhance student learning experience and entrepreneurial skills. South African Journal of Higher Education. 33(6):191‐214.

Mbatha, B. (2013). Beyond distance and time constrictions: Web 2.0 approaches in open distance learning, the case of the University of South Africa (UNISA). Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(14), 543-543.

Mei, D. 2022. What does students’ experience of e‐portfolios suggest? Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences. 7(2): 15‐20.

Miller, R., & Morgaine, W. (2009). The benefits of ePortfolios for students and faculty in their own words. Peer review, 11(1), 8-12.

Modise, M. P. (2021). Postgraduate students’ perception of the use of ePortfolios as a teaching tool to support their learning in an open and distance education institution. Journal of Learning for Development. Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 283-297

Mollo, P. P., Thabane, R. W., &Lenong, B. (2022). Reflection on the use of eportfolios during teaching practicum at a university of technology in South Africa. Education and New Developments 2022. https://doi.org/10.36315/2022v1end013

Ngakane, B., & Madlela, B. (2022). Effectiveness and policy implications of using WhatsApp to supervise research projects in open distance learning teacher training institutions in Swaziland. Indiana Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(3), 1-10.

Ngubane-Mokiwa, S. A. (2017). Implications of the University of South Africa’s (UNISA) shift to open distance elearning on teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(9), 7.

Oh, J. E., Chan, Y. K., & Kim, K. V. (2020). Social media and ePortfolios: impacting design students’ motivation through project-based learning. IAFOR Journal of Education, 8(3), 41-58. https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.8.3.03

Puleng Modise, M. E., & Vaughan, N. (2024). ePortfolios: A 360-Degree Approach to Assessment in Teacher Education. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 50(4), 1-18.

Schutz-Pitan, J., Seidl, T., &Hense, J. (2020). Effectiveness of cross-curricular and cross-modular ePortfolio use in higher education teaching. Factors influencing competency acquisition. Contributions to practice, practical research, and research, Volume 2019 , 769.

Sharifi, M., Soleimani, H. & Jafarigohar, M. (2016). ePortfolio evaluation and vocabulary learning: Moving from pedagogy to andragogy. British Journal of Educational Technology,48(6), 14411450. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12479

Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2010). Learning presence: Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the development of a communities of inquiry in online and blended learning environments. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1721–1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.07.017

Sithole, B. M. (2011). Portfolio Assessment of Teaching Practice: Views From Business Education In-Service Student Teachers in Botswana. Online Submission.

Totter, A., & Wyss, C. (2019). Opportunities and challenges of ePortfolios in teacher education. Lessons learnt. Research on Education and Media, 11(1), 69-75. DOI:10.2478/rem-2019-0010

Tur, G., & Urbina, S. (2016). La colaboracióneneportafolios con herramientas de la Web 2.0 en la formacióndocenteinicial [Collaboration in ePortfolios with Web 2.0 tools in initial teacher training]. Cultura y Educación, 28(3), 601–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2016.1203528

Tyroller, M., Walter, M. S., Riess, C., & Altieri, M. (2023). Lessons learned: futrher strategies for the implementation of eportfolios in engineering sciences. In DS 123: Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE 2023).

Walland, E., & Shaw, S. (2022). ePortfolios in teaching, learning and assessment: tensions in theory and praxis. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(3), 363-379.

Welsh, M. (2012). Student perceptions of using the Pebble Pad ePortfolio system to support self-and peer based formative assessment. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 21(1), 57-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2012.659884

Wenger, E., Wenger-Trayner, B., Reid, P., & Bruderlein, C. (2023). Communities of practice within and across organizations: a guidebook. Social Learning Lab.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179–198). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_11

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2023). Collaborative ePortfolios use in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A co-design strategy. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 9(3), 585-601. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.9.3.585

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2022). Educational ePortfolio overview: Aspiring for the future by building on the past. IAFOR Journal of Education, 10(3), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.10.3.03

AUTHOR

Dr. Benkosi Madlela is currently engaged by the University of Johannesburg (UJ) in South Africa as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow. Dr Madlela conducts research and presents papers in international conferences, publishes journal articles and book chapters and contributes solutions to the body of knowledge. He is also a peer reviewer for some journals that are accredited by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Dr Madlela believes that if Africa is to prosper economically, its organisations in the public and private sectors should invest in research, decolonised education and training. His ideology centres round the African Philosophy, education with production for self reliance and the Spirit of Ubuntu.

Email: benkosimadlela@gmail.com