41 Personalising ePortfolio Design through Reflexive Learning Analytics Practices

Mashite Tshidi

University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The expansion of digital learning has positioned ePortfolios as vital for fostering 21st-century competencies, including digital literacy, adaptability, reflexivity, and personalised learning in higher education. Simultaneously, learning analytics, encompassing the measurement, collection, analysis, and reporting of student data, offer new avenues for optimising learning experiences and supporting personalised learning environments. However, integrating learning analytics into ePortfolio design remains underexplored, particularly in addressing the diverse and evolving needs of students. This chapter explores how learning designers engage reflexively with learning analytics and how such engagements inform the creation of student-centred ePortfolios. Anchored in the Community of Inquiry framework, which foregrounds the interrelationship among cognitive, social, and teaching presences, the study employs a multiple case study design using qualitative methods. Six learning designers across three higher education institutions, recognised for their expertise in ePortfolio development, participated in video-stimulated recall interviews to surface the decision-making processes that shape their designs. Through thematic analysis, key patterns emerged illustrating how learning analytics enhanced personalisation strategies, with data-driven insights informing the design of adaptive, authentic, and student-directed ePortfolios. Cognitive presence was strengthened through the early identification of at-risk students and the monitoring of engagement indicators, such as task completion and login activity. Social presence was nurtured by incorporating student voices into design decisions and fostering global collaborations around learning analytics. Teaching presence was reinforced through data-informed learning refinements and responsive feedback mechanisms. These findings underscore the role of reflexive, evidence-based practices in advancing scalable, localised, and commercially viable ePortfolio designs.

Keywords: ePortfolios, Learning Analytics, Personalised Learning, Reflexivity, Community of Inquiry, Learning Design

INTRODUCTION

The increasing digitalisation of higher education has reshaped how teaching, learning, and assessment are conceptualised. Amid these shifts, ePortfolios have emerged as dynamic digital platforms that support reflective, personalised, and collaborative learning (Korhonen et al., 2020). Typically, an ePortfolio is a self-curated electronic collection of evidence demonstrating a student’s knowledge, skills, and abilities. Beyond storing artefacts, ePortfolios encourage critical reflection, showcase achievements, and support ongoing professional development (Modise & Vaughan, 2024), allowing students to weave academic content and personal growth into a cohesive learning narrative.

Situated within the broader development of personalised learning environments (PLEs). ePortfolios represent a contemporary approach to organising learning in digital spaces. PLEs are characterised by students’ capacity to select the online resources, networks, and formal and informal learning processes required to develop abilities for the modern workforce (Korhonen et al., 2020). By integrating learning objectives with individual autonomy and reflection, ePortfolios offer a concrete expression of personalised, self-directed learning within these environments (Carroll et al., 2023).

While the pedagogical benefits of ePortfolios are well recognised, their implementation is not without difficulty. Students often struggle with the breadth of tasks, the required timelines, making clear links to learning outcomes, engaging in deep reflection, and effectively demonstrating their skills (Korhonen et al., 2020). De Ruyck et al. (2024) observe that while technological advances have transformed ePortfolio platforms, feedback practices have not evolved simultaneously. Feedback has largely remained text-based, a legacy of paper-based traditions, which limits opportunities for more dynamic, multimedia-driven feedback experiences. Moreover, a notable gap remains in research on the effective use of feedback formats within ePortfolios, which constrains how these platforms can be optimally designed to support iterative learning and development.

These challenges are significant in light of the broader shift towards data-driven decision-making in education. Learning analytics, which refers to the systematic measurement, collection, analysis, and reporting of data about students and their contexts, offers promising avenues to optimise learning environments (Mougiakou et al., 2023). By organising and interpreting student data, learning analytics provide actionable insights that support the tracking of student actions, integration with external data sources, and identification of meaningful learning patterns (Hooda & Rana, 2020). Empirical research has demonstrated the benefits of learning analytics in monitoring student progress, modelling learning behaviours, detecting affective states, predicting outcomes such as performance and retention, and delivering personalised recommendations (Hooda & Rana, 2020; Mougiakou et al., 2023). When applied to ePortfolio-based learning, these capabilities can foster critical reflection, promote self-regulated learning, and provide timely and responsive feedback (Pospíšilová & Rohlíková, 2023).

Within this ecosystem, learning design, as the systematic planning and structuring of learning experiences to achieve specific educational goals (Mangaroska & Giannakos, 2018), emerges as an enabler of personalised and adaptive learning. Integrating learning analytics into learning design processes offers opportunities for data-informed pedagogical strategies. However, research in this area has focused on the course or institutional level, with limited attention to how learning designers interpret and apply analytics when shaping personalised learning experiences, such as ePortfolios (Drugova et al., 2024). This presents a critical gap, particularly as higher education institutions strive to foster culturally responsive, student-centred learning environments (Rizvi et al., 2024).

Against this backdrop, this study aims to investigate how learning designers utilise learning analytics to inform reflexive and adaptive practices in the design of ePortfolios. Anchored in the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework, which emphasises cognitive, social, and teaching presences as foundational to meaningful online learning experiences, this study explores the intersection of data-informed insights and pedagogical innovation. To achieve this aim, the following research questions were developed to guide the inquiry:

- How do learning designers use learning analytics to inform the design of ePortfolios?

- What reflexive practices do learning designers use when integrating learning analytics into their ePortfolio design processes?

LITERATURE REVIEW

ePortfolios in Higher Education

In higher education, ePortfolios have grown prevalent as a student-centred strategy to promote digital literacy, reflective practice, and lifelong learning. As a learning process, ePortfolios contain digital artefacts, individual reflections on both formal and informal learning experiences, collaborative tasks, research projects, and academic achievements (Modise & Vaughan, 2024). By providing students with opportunities to curate multimodal information, such as text, audio, video, and graphics, they develop both academic and digital skills that are essential to contemporary learning. As a result, ePortfolios facilitate reflective engagement, authentic assessment, and knowledge co-construction using recursive peer and learning content interaction (Modise & Mudau, 2023).

Despite their pedagogical value, the integration of ePortfolios in online and resource-constrained environments remains uneven. Research identifies tensions related to the time required to complete tasks, the need for technical support, and difficulty making links between artefacts and learning outcomes (Modise & Mudau, 2023). There is also uncertainty about how students interpret feedback and how this shapes their learning process. These issues have prompted a broader discourse about the effectiveness of current ePortfolio practices in terms of student agency and engagement.

Learning Analytics and the Feedback Dilemma

To support the efficacy of ePortfolios, recent scholarship emphasises the relevance of learning analytics in improving feedback and supporting student agency. Defined as the collection, analysis, and reporting of data about students and their contexts to comprehend and optimise learning and the environments in which it occurs (Mougiakou et al., 2023), learning analytics presents opportunities for timely, personalised, and actionable feedback. In ePortfolio contexts, feedback can be informed by data patterns related to engagement, progression, and peer interaction, rather than relying solely on subjective interpretation.

However, there are tensions in how feedback is designed and interpreted in data-informed environments. While analytics can generate detailed insights, they do not inherently translate into meaningful or motivational feedback. Hooda and Rana (2020) argue that analytics-driven feedback must be consistent with students’ goals, values, and interpretations to be practical. However, most studies focus on how students receive feedback, rather than how they give it or co-construct meaning in peer interactions. This highlights a gap in understanding how feedback operates dialogically within ePortfolios and how learning analytics can support participatory feedback loops, rather than relying solely on top-down approaches (De Ruyck et al., 2024).

Furthermore, despite technological advances in ePortfolio platforms, feedback practices remain primarily text-based and teacher-centred. De Ruyck et al. (2024) note that feedback formats have not kept pace with platform innovations, thereby limiting the potential for multimodal, dynamic feedback experiences. Hunt et al. (2021) argue that reconceptualising feedback as a complex interaction between students, systems, and artefacts could provide potential opportunities for analytics-informed design.

Learning Design, Reflexivity, and Systemic Integration

The design of ePortfolio tasks is often guided by learning design principles that promote coherence between pedagogical intent, assessment practices, and analytics. Learning design provides a blueprint for creating meaningful learning experiences and facilitates the integration of learning analytics to support both teaching and learning (Mangaroska & Giannakos, 2018). Conceptual frameworks such as Law and Liang’s (2020) multi-level model and Learning Analytics for Learning Design (LA4LD) (Mangaroska & Giannakos, 2018) demonstrate how analytics can inform course quality, scaffold metacognitive development, and support design decisions. The complexity of learning design is often reflected in these frameworks’ multilevel structure, explicit guidance for decisions at various levels, integration of learning analytics taxonomy and design choices into the design process, aid in the development of cohesive technological-pedagogical content patterns for reuse, and procedural recommendations to assist teachers in concentrating on essential pedagogical factors.

However, despite the promise of integrating analytics into learning design, these two domains often remain siloed in practice. A key tension is that learning design is grounded in pedagogical reasoning, whereas technical considerations typically drive analytics. According to Drugova et al. (2024), analytics may be misused or underused in the absence of interpretive, pedagogically informed reflection. Learning designers must draw inferences from analytics in ways that align with learning objectives; however, there is limited research on how they achieve this in ePortfolio contexts.

This raises the importance of reflexive practice in learning design. Reflexivity enables designers to question assumptions, interpret analytics through pedagogical lenses, and adapt designs responsively (Dlamini & Makda, 2024). In ePortfolio settings, reflexivity may inform decisions about feedback loops, task scaffolding, and student autonomy. However, few studies explore how learning designers engage in reflexive practices when designing data-informed ePortfolios. Moreover, the role of reflexivity in navigating tensions between standardised data and personalised learning experiences remains under-theorised (Drugova et al., 2024).

Gaps in the Literature

Although substantial research has been conducted on ePortfolios, learning analytics, and learning design, their integration is fragmented. Much of the literature treats each component in isolation: ePortfolios as reflective tools, analytics as dashboards or predictive models, and learning design as structured plans. What is missing is an exploration of how these components work together through the lens of reflexive and adaptive learning design. There is limited empirical evidence showing how learning analytics enhances feedback quality, student agency, or adaptive design in ePortfolio-based learning (Pospíšilová & Rohlíková, 2023). Frameworks such as the CoI model provide a structure for embedding reflexive practice, focusing on the interplay of cognitive, social, and teaching presence in online learning environments (Garrison et al., 2000). However, few studies apply such frameworks to the intersection of learning analytics and ePortfolio design. This leaves a conceptual and practical gap in understanding how reflexive learning designers use analytics to inform feedback, foster engagement, and adapt ePortfolio practices in response to student data. This study aims to address these gaps by examining how learning designers utilise learning analytics to inform reflexive, adaptive learning design in ePortfolio contexts.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

A conceptual framework provides a theoretical basis for a study’s design, analysis, and interpretation. This study draws on Garrison et al.’s (2000) CoI framework, which has become the cornerstone for examining learning in online and blended environments. The CoI framework comprises three interdependent elements: cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence, each of which is essential for creating a meaningful educational experience in digital learning spaces, such as ePortfolios. While initially conceptualised to understand student learning, this study recontextualises the CoI to examine how learning designers integrate these presences into ePortfolio-based learning environments that support reflexive practices and are enhanced by learning analytics.

Cognitive presence emphasises the use of critical thinking and sustained reflection to construct and reinforce meaning. Since it enables students to integrate previously learned content with newly acquired knowledge, this process is essential to the CoI as it fosters cognitive engagement and skill development (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007). This development manifests through three stages of cognitive presence, including triggering events (identifying challenges or problems that prompt inquiry), exploration (conducting brainstorming sessions and knowledge discovery), and integration (combining information to create understanding and apply knowledge in meaningful ways) (Garrison et al., 2000). Learning designers should consider the latter factor when choosing digital resources and scaffolding tasks that encourage critical reflection, iterative meaning-making, and linking ePortfolio artefacts to learning objectives.

A sense of connection and cooperation is fostered by social presence, which can be characterised as an individual’s capacity to demonstrate both social and emotional attributes in a learning community. Among its hallmarks are group cohesion, which creates trust and a shared objective, subsequently bringing participants together to create a collaborative community; open communication, which fosters meaningful dialogue and mutual understanding; and emotional expression, which promotes the sharing of personal values and perspectives to build interpersonal bonds (Garrison et al., 2000). To foster a sense of community despite the digital modalities in which ePortfolios are situated, provide opportunities for peer interaction, feedback, and discussions (Korhonen et al., 2020).

The social and cognitive aspects of learning are supported and integrated by teaching presence, which includes direct instruction, facilitation, and learning design (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007). Garrison et al. (2000) emphasised the interplay between social and teaching presences, arguing that encouraging meaningful interactions is essential to developing both social and teaching presences. Fundamentally, teaching presence is about organising, directing, and assisting the learning process while making sure it is meaningful and results-oriented. This is delivered through three key elements: design and organisation, facilitating discourse, and direct instruction. Design and organisation entail structuring the curriculum, configuring the digital environment, and corresponding assessment procedures with reflective goals. These aspects set the foundation for direct instruction, broadening learning by promoting inquiry, outlining expectations, synthesising feedback, and incorporating various subject sources. Facilitation also entails using feedback tools, such as learning analytics reports, to guide students’ progress, promote engagement, and support sustained reflection over time.

Engaging with an ePortfolio as a learning tool requires a certain level of digital competence, enabling students to interact productively with the content, the teacher, their peers, and the technological interface to achieve specific learning outcomes. Garrison et al. (2000) assert that a CoI is created when people actively and cooperatively participate in discourse and reflection to create shared meaning and personal understanding. In digital environments, including ePortfolio platforms, teachers must retain a visible presence while also encouraging learners to interact actively. This presence is demonstrated through intentional participation, preparation, efficient use of digital technologies, peer collaboration, and ongoing self-monitoring through reflective practices. For this reason, to ensure that learning occurs, the technologies chosen for online learning should make it feasible for students to interact meaningfully with peers, the teacher, and the content (Modise, 2021). In light of this understanding, the study draws on the CoI framework to examine the situated use of learning analytics tools by learning designers in shaping ePortfolio-based learning environments that promote reflexivity and collaborative engagement.

METHODOLOGY

Research Design

This study employed a qualitative multiple-case study design to explore how learning designers utilise learning analytics to inform reflexive and adaptive practices in the design of ePortfolios in higher education. Such a design was well-suited to capturing the complexity and diversity of individual experiences, as each learning designer represented a bounded case within their institutional context. Building on this approach, the case study design enabled a context-sensitive examination of the phenomenon across multiple institutional settings. The interpretivist paradigm was deemed appropriate due to its emphasis on understanding individuals’ experiences and the meanings they ascribe to their actions (Lim, 2024). This stance was consistent with the study’s aim, as it foregrounded participants’ perspectives and the socially constructed nature of their practices (Merriam & Grenier, 2019). By privileging these subjective accounts, the interpretivist lens provided a means to identify participants whose experiences could inform contextually grounded practices and situated insights that emerge from engagement with learning analytics in ePortfolio-based learning environments.

Sampling

Purposive sampling was used to identify participants who met specific inclusion criteria relevant to the study’s objective. These criteria specified that participants must: (1) hold a position as a learning designer within a South African higher education institution, (2) have a minimum of three years’ experience in learning design, and (3) demonstrate practical engagement with learning analytics in the design or support of ePortfolio-based learning. To extend the reach of this recruitment process, snowball sampling was additionally implemented, enabling the identification of further suitable candidates through professional referrals where direct access was constrained. Through these integrated strategies, a total of six learning designers, each from a distinct institutional context, were selected. This group constituted a diverse yet focused sample, deemed adequate to generate context-specific insights while supporting meaningful cross-case analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2016).

Data collection

The primary data collection method was video-stimulated recall interviews, which were used to elicit reflective insights into design practices. Participants were first invited to create short screen-capture recordings that illustrated how they interacted with learning analytics data when making ePortfolio-related design decisions. These self-recorded videos served as contextual anchors for the subsequent semi-structured interviews, helping to prompt recall and deepen reflection during the discussion (Nicholas et al., 2018). Therefore, by linking observed actions to underlying reasoning, this method illuminated the procedural and cognitive dimensions of learning design.

All interviews were conducted virtually, using either Microsoft Teams or Zoom, according to the participant’s preference. Each session was recorded and transcribed verbatim, with transcription supported by ATLAS.ti and cross-checked for accuracy by the researcher. The interview protocol was developed based on a synthesis of relevant literature and the study’s core research questions. To enhance clarity and relevance, a pilot interview was conducted, and the protocol was subsequently refined. This revision process ensured that the final questions captured the reflexive deliberations and adaptive strategies that would support a rigorous analysis of design practices (Stefaniak et al., 2025).

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted using Braun and Clarke’s (2020) reflexive six-phase framework, which provided a structured approach to identifying, analysing, and interpreting patterns across the dataset. The process commenced with a detailed familiarisation with the transcribed interviews, allowing the researcher to immerse themselves in the data and begin recognising preliminary meanings. Subsequently, initial codes were developed systematically to capture salient features relevant to the research questions. A combination of deductive and inductive coding strategies was employed to maintain analytical depth and openness. Deductive codes were informed by the interview protocol and the study’s conceptual framing. In contrast, inductive codes were allowed to emerge organically from the data itself, enabling the discovery of unexpected insights and participant-driven themes. This integrative approach supported a balanced interpretation of the data (Byrne, 2022). ATLAS.ti software was used to manage, retrieve, and analyse the data to support the coding process and enhance data traceability. Following the coding phase, emergent themes were refined, reviewed, and situated within the dimensions of the Community of Inquiry framework to maintain conceptual coherence. Each theme was subsequently defined and named to reflect its meaning, and representative quotes were selected to illustrate participants’ lived experiences.

Ethical considerations

This study complied with ethical requirements for research involving human participants, guided by the Belmont Report’s principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979). Clearance was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand’s Human Research Ethics Committee before data collection. Participants received an information sheet and consent form, and were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained by removing identifying details from transcripts and advising participants not to disclose sensitive information during screen recordings. A further challenge arose when video data revealed institutional names and branding, creating risks to anonymity; accordingly, screenshots were excluded from reporting. Interview data were stored in password-protected folders accessible only to the researcher, ensuring participants could engage openly and reflectively.

FINDINGS

The study’s findings are presented thematically to demonstrate how learning designers use learning analytics to inform the creation of student ePortfolios in higher education contexts. Rather than being predetermined at the outset of the study, the topics were produced deductively and inductively through a thorough thematic analysis of interview transcripts. This emergent approach facilitated the development of connections with the conceptual basis of the CoI framework while preserving the research’s groundedness in participant experiences. As advised by Lim (2024), the findings are presented narratively to uphold the truth value of the participants’ viewpoints and to preserve authenticity. Drawing on the viewpoints of six carefully selected learning designers working on the design of learning analytics-informed curricula, the discussion explores how data-driven decisions are used to scaffold student engagement, promote reflection, and support the creation of meaningful ePortfolios.

Theme 1: Enhancing cognitive presence through analytics-driven backwards design

The strategic integration of learning analytics and backwards design to improve ePortfolio-based learning experiences iteratively is a central theme that emerged from the interviews. In all of the interviews, participants explained how learning activities, assessments, and outcomes were developed using backwards design principles. Participant A explained, “So, at the beginning, teachers have to map their planned learning design. And then working with a lot of people, we try to optimise the learning design before the module goes live into what we call presentation mode.”

This methodical planning procedure facilitates the creation of ePortfolios as tools for reflection and as evidence of learning. With this method, ePortfolios are integrated into the learning process from the beginning, rather than being reflective add-ons. Participant B stated, “We encourage lecturers to make the ePortfolio tasks part of the initial design; they should be integrated with outcomes and assessment criteria.” This is consistent with Chun-Burbank et al. (2023), who implemented an ePortfolio capstone in a bachelor’s program using a constructivist, backwards design approach. Learning outcomes guided the design of the course assignments, enabling their applicability to the ePortfolio. The ePortfolio was used for program review and student learning assessment. Before submitting their final portfolios, students received formative feedback on their output, which encouraged iterative learning and helped them achieve the intended outcomes.

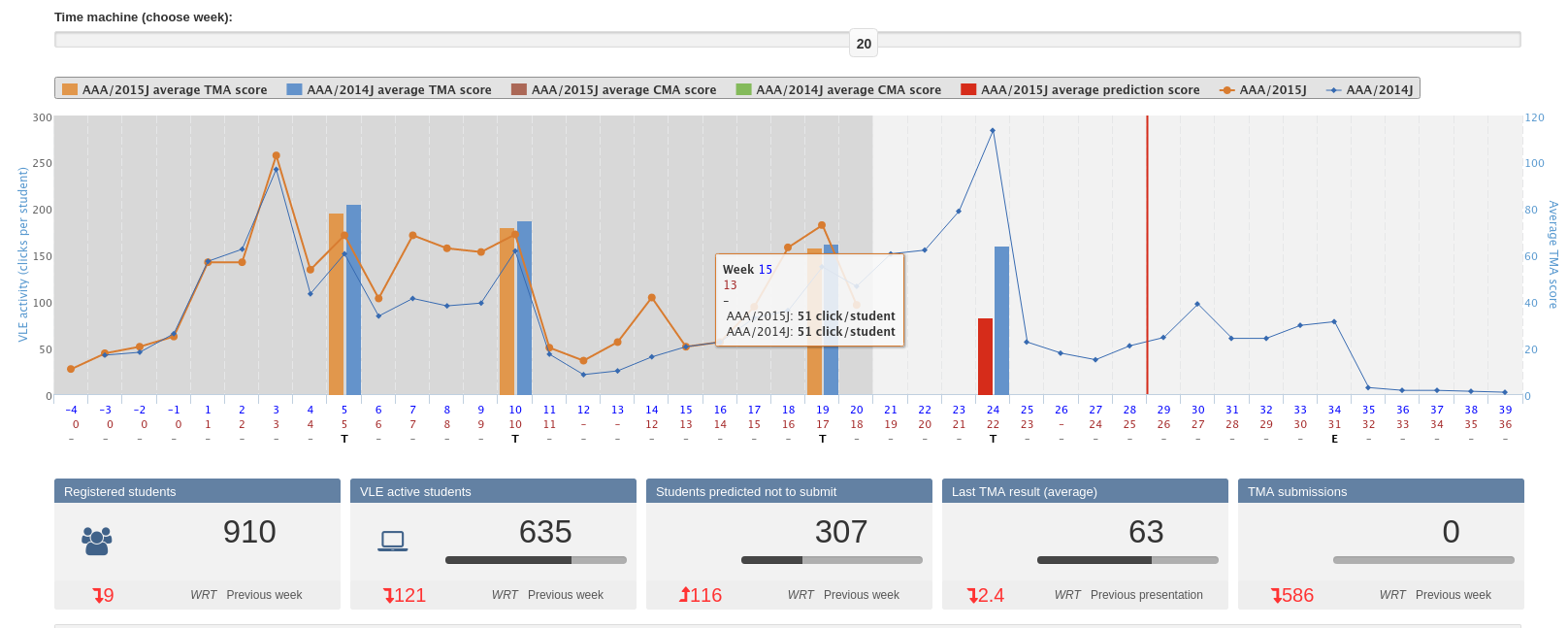

Once modules transition to presentation mode, lecturers can start tracking student engagement using learning analytics dashboards, which display trends in how students interact with ePortfolio activities and other components, as seen in Figure 1. Participant A provided that “these dashboards give us a clear view of how students are engaging, week-by-week or even day-by-day.”

Figure 1

An Instance of a Module in the Learning Analytics Dashboard

Such dashboards help teachers track task progression, submission patterns, and the quality of reflections. Participants noted that when students fail to engage with early scaffolded reflections or multimodal artefacts, this can trigger immediate pedagogical responses. For example, the absence of weekly reflection entries suggests that the final integrated ePortfolio could be underdeveloped. This is consistent with the capabilities of checkpoint analytics, which can help determine when student engagement aligns with or deviates from the intended pedagogical direction (Mougiakou et al., 2023).

Participants further explained that institutional meeting opportunities offered structured reflection points throughout the academic year, enabling educators to refine instructional strategies and ePortfolio activities in response to observed engagement trends. Participant A stated, “With Analytics for Action, teachers have the opportunity two or three times a year to discuss what’s going well, what’s not going so well, and what changes could be made during or after the presentation.” This iterative feedback cycle reflects Mangaroska and Giannakos’s (2018) assertion that learning analytics can only improve learning when grounded in sound pedagogical design. When ePortfolios are constructed to allow students to select areas for feedback and reflection, they promote ownership of learning. When used in this way, resources such as ePortfolios transform from static repositories into dynamic assessment contexts that are shaped by ongoing interactions between teachers and students (Hunt et al., 2021). According to Lim et al. (2021), analytics-supported feedback is effective when it aligns with students’ interests and values, thereby supporting their self-regulation. In a similar vein, Pospíšilová and Rohlíková (2023) emphasise that resources intended to encourage reflection must give teachers ownership of the procedure, leading to feedback that is pertinent, timely, and useful.

In ePortfolio-based learning, where tasks accumulate over time, participants reflected on the use of learning analytics in identifying and assisting at-risk students, particularly those who fall behind on reflective tasks or miss deadlines. As reflected by Participant B: “Our clients are the lecturers, and we support them by teaching them how to identify at-risk students. However, it doesn’t stop there. It’s crucial to determine how to intervene once a pattern of risk is identified.” This suggests that a missing reflection or artefact can affect the end product at any phase. Participant C underlined this risk: “If 50% of students do not submit an assignment, it’s not enough to just report that. We need to intervene by asking, “What can we do to make sure they submit?” The notion that learning analytics functions optimally when linked to pedagogical action is reinforced by the focus on timely intervention (Mougiakou et al., 2023). In ePortfolios, this commences with collecting data, including submission timestamps, access frequency, and reflection depth. These data are analysed to identify patterns related to the performance and engagement of the students. These patterns are subsequently presented by reporting tools in summaries or dashboards, which help educators make informed decisions. Action is the last and most important stage. This could entail revising reflective prompts, adjusting assignment schedules, or reaching out to students to encourage their engagement in ePortfolio practice (Pospíšilová & Rohlíková, 2023). Thus, learning analytics serves as a descriptive tool and a mechanism for pedagogical recalibration.

On a broader scale, some participants described how learning analytics data from ePortfolio components is assembled for program-level review. Participant C explained, “We use a pyramid analysis to view data at different levels—subject, program, and institutional. This gives us an understanding and allows for scalable interventions.” In this way, individual unit findings contribute to strategic discussions regarding graduate attribute development and curricular coherence, where ePortfolios are used to assess traversing skills such as critical thinking, digital literacy, and identity development (De Ruyck et al., 2024; Modise & Mudau, 2023). This pertains to the CoI framework, primarily in terms of cognitive and teaching presence, because the participants outlined that lecturers employ analytics to assist students in generating meaning across time through reflection and integration, both of which constitute essential aspects of ePortfolio activity. Analytics dashboards support lecturers in guiding students through extended periods of reflection by supporting both triggering events and integration stages (Sun et al., 2021). As a result, by identifying moments where reflection was superficial or progress stagnated, lecturers were better equipped to re-engage students.

It emphasises immediate pedagogical responsiveness, which sets this approach apart from traditional post-hoc discourse analysis, which often examines completed reflective artefacts to infer learning. This study found that learning analytics were used not only for retrospective evaluation but also to enable timely instructional interventions while ePortfolios were being constructed. With this shift, learning designers and lecturers can identify areas where students lack reflective depth or are disengaged and provide targeted support that promotes formative engagement. This strategy supports the contention made by Çakiroğlu and Kahyar (2022) that learning analytics should actively support sustaining cognitive presence during the learning process rather than merely measuring engagement after the fact. Consequently, the study’s findings demonstrate how analytics can function as integrated feedback mechanisms in ePortfolio-based learning design.

Theme 2: Reinforcing social presence through multidisciplinary collaboration and feedback loops

Multidisciplinary collaboration evolved as a critical design element that fostered the creation of responsive and inclusive ePortfolio environments. Participants remarked how design teams integrated various expertise to co-construct learning paths that considered student realities and institutional priorities. This collaborative approach promoted flexibility and early intervention, especially for distance students whose participation could not be tracked face-to-face. Participant A explained:

We brought people from IT who are running the virtual learning environment and people running a student services system. We brought people in from the library, programmers, teachers, and student support. We brought these people together because they provide unique perspectives on the student journey. And I think that is key, that it’s interdisciplinary.

This design culture mirrored Rienties et al.’s (2017) process-oriented model, in which educational decisions are made through discourse and collaborative interpretation of student data. Similar to earlier research, this process-oriented model acknowledges that cooperative methods promote social presence by fostering mutual understanding, trust, and responsiveness between teachers and students. However, this study builds on these insights by applying them in the context of ePortfolio design, where reflection and structured student input are central to success. Integrating learning analytics tools enabled teams to monitor student progress, collectively understand behavioural patterns, and alter instructional components as needed.

Unlike prior work, which has primarily concentrated on the instructional benefits of collaboration (Korhonen et al., 2020), this study foregrounds the role of feedback loops as mechanisms for social presence within analytics-enhanced ePortfolio pedagogy. Participants described how their teams employed an iterative approach to ePortfolio structure, allowing for continual refinement based on student feedback and usage data. For example, they incorporated LMS tools such as Google Forms to gather student feedback on workload, task clarity, and pacing. Participant F described that “the feedback revealed that students felt overwhelmed. Adjusting the pacing and workload based on their input led to increased satisfaction and retention.” These micro-feedback loops provided timely adjustments to prompt sequencing, guidance granularity, and level of tutor support. In this instance, social presence was regarded as a structural aspect of the design process, embedded through shared institutional accountability and iterative data use, rather than merely a relational or communicative construct.

A key distinction from much of the current literature is that previous research frequently views students as beneficiaries of design decisions (Drugova et al., 2024); this study included their voices through post-implementation data collection and analytics interpretation. Considering their omission from the initial co-design phase, students’ feedback shaped subsequent refinements. Though it falls short of its necessity for early-stage co-creation, this is partly consistent with the participatory design ethos (Dollinger et al., 2019). This reactive rather than proactive style of student involvement is both a limitation and a starting point for future research to investigate the impact of integrating student viewpoints earlier in the design process.

Theme 3: Expanding teaching presence through contextual adaptation and scalability

The study found that teaching presence expanded beyond traditional instructional roles and grew into a dynamic, data-driven process of scalable learning design and contextual adaptation. Participants noted that ePortfolio tasks, resources, and reflection prompts are embedded within students’ sociocultural and institutional contexts. This personalised approach was essential for meaningfully engaging students, particularly in post-apartheid higher education settings where standardised content often fails to resonate with students’ lived experiences (Steyn, 2024). Participant D captured this emphasis succinctly: “Personalisation involves creating learning that is individualised, contextualised, and relevant to learners’ realities.” This finding is consistent with the literature on culturally responsive design, which stresses the pedagogical advantages of situating learning activities within students’ social and cultural contexts (Gay, 2018). However, this study broadens the discussion by including localisation into the ePortfolio design process through the iterative use of learning analytics.

Participants explored the use of data from LMS tools, submission patterns, and feedback to detect disengagement, refine artefact prompts, and adjust pacing or guide approaches as needed. This continuous, data-driven adjustment process reflects a shift in perspective from perceiving teaching presence as a one-time planning task to understanding it as a flexible and ongoing orchestration of instruction. Previous research frequently frames teaching presence as a function of interactions between teachers and students (Garrison et al., 2000). The findings of this study suggest that teaching presence is integrated into the ePortfolio design, responding to the evolving needs of a diverse student body.

The emphasis on contextual relevance also paved the way for discussing the expansion of ePortfolio learning into modular and commercial models. Participants noted a shift toward micro-credentials and commercial platforms for providing stackable, skill-based ePortfolio tasks that coincide with workplace objectives. Participant E explained, “The idea behind micro-credentials is to stack them up towards getting a qualification. You can do bits and pieces of mathematics or physics, and ultimately, over the years, build it up towards getting a degree.” Participant C elaborated on how ePortfolios can integrate with these platforms: “We also have a license to LinkedIn Learning, which is integrated within Blackboard… You can have three- or two-minute videos demonstrating or outlining the same concept you are teaching your students… link them back to Blackboard as support material.”

Although this focus on scalability is comparable to trends in workforce-aligned credentials and lifelong learning (Moore et al., 2025), ePortfolios are viewed as integrative spaces where skill acquisition, personal development, and institutional learning converge, rather than as standalone showcases. The study thus suggests a twofold trajectory in teaching presence: one is based on contextual responsiveness and the other on strategic modularity for broader uptake. A critical insight from this twofold trajectory is that the ePortfolio context cannot be divorced from sociocultural relevance or infrastructural foresight. The findings suggest that using analytics as a design process, rather than a monitoring tool, demonstrates how presence can be fundamentally integrated at the institutional, pedagogical, and individual levels.

CONCLUSION

This study examined how learning designers in higher education utilise learning analytics to inform the design of ePortfolio-based learning experiences. Using the CoI framework as a conceptual lens, the findings illustrated that analytics-enhanced design processes can scaffold cognitive presence through backwards design and feedback cycles, reinforce social presence via multidisciplinary collaboration and iterative refinement, and improve teaching presence through contextual adaptation and scalable practices. These findings extend prior work by demonstrating that learning analytics can support evaluation and shape pedagogical design (Drugova et al., 2024; Mangaroska & Giannakos, 2018).

This assertion is consistent with studies such as Pospíšilová and Rohlíková (2023), which suggest that learning analytics could assist with timely interventions, facilitate reflection, and integrate student engagement with learning objectives to play a formative and reflexive role in the development of ePortfolios. Analytics tools were employed by learning designers and teachers to inform instructional decision-making throughout the learning process, rather than functioning as retroactive performance monitors, as is commonly mentioned in the literature. This highlights the importance of integrating analytics into authentic learning contexts, where data and students’ lived experiences inform design decisions.

Although analytics-driven teaching presence improved lecturer interventions, the study did not specifically examine long-term student learning outcomes of their ePortfolio development. The degree to which these data-driven adjustments impacted student understanding, retention, or learning remains unknown, despite indications that lecturers revised their instructional approaches in response to performance metrics. This limitation suggests that the study’s findings may not have adequately accounted for learner presence. Future research should include longitudinal studies to measure the long-term impact of analytics-driven learning design on student ePortfolio engagement and performance.

The study’s scope was limited to six instructional designers from three higher education institutions in South Africa. Although this provided context-specific insights, the findings may not be as generalisable to broader contexts due to the small sample size. Furthermore, the emphasis placed on ePortfolios in these institutions may not accurately represent the diverse ways that learning analytics can be applied across various platforms, disciplines of study, or institutional cultures.

These limitations do not detrimentally affect the findings’ conceptual and practical value, but they suggest caution when extrapolating them. With a nuanced account of how analytics can enhance presence, responsiveness, and reflexivity in ePortfolio learning, this study contributes to the growing literature on learning analytics-informed pedagogy. As higher educational institutions increasingly turn to data to guide their decisions, it becomes desirable and essential to anchor these practices in learner-centred, participatory, and contextually grounded approaches to ensure that the ePortfolio-based learning experience is meaningful and equitable.

REFERENCES

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

Carroll, D., Uribe-Flórez, L. J., Ching, Y. H., Perkins, R., & Figus, E. (2023). Understanding learners’ experiences of using ePortfolio in a high school physics course. TechTrends, 67(6), 977–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00908-z

Chun-Burbank, S., Payne, K., & Bartlett, C. (2023). Designing and implementing an ePortfolio as a capstone project: A constructivist approach. International Journal of ePortfolio, 13(1), 11–20.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications.

De Ruyck, O., Embo, M., Morton, J., Andreou, V., Van Ostaeyen, S., Janssens, O., Robbrecht, M., Saldien, J., & De Marez, L. (2024). A comparison of three feedback formats in an ePortfolio to support workplace learning in healthcare education: A mixed method study. Education and Information Technologies, 29(8), 9667–9688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12062-3

Dlamini, R., & Makda, F. (2024). Sustainable interactive remote teaching and online learning: A reflexivity case study. The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning, 19(2), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.17159/x9dvf915

Drugova, E., Zhuravleva, I., Zakharova, U., & Latipov, A. (2024). Learning analytics driven improvements in learning design in higher education: A systematic literature review. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(2), 510–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12894

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2–3), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Hooda, M., & Rana, C. (2020). Learning analytics lens: Improving quality of higher education. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Engineering Research, 8(5), 1626–1646. https://doi.org/10.30534/ijeter/2020/24852020

Hunt, P., Leijen, Ä., & van der Schaaf, M. (2021). Automated feedback is nice, and human presence makes it better: Teachers’ perceptions of feedback by means of an ePortfolio enhanced with learning analytics. Education Sciences, 11(6), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060278

Korhonen, A. M., Ruhalahti, S., Lakkala, M., & Veermans, M. (2020). Vocational student teachers’ self-reported experiences in creating ePortfolios. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 7(3), 278–301. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:21231

Lim, L. A., Gentili, S., Pardo, A., Kovanović, V., Whitelock-Wainwright, A., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2021). What changes, and for whom? A study of the impact of learning analytics-based process feedback in a large course. Learning and Instruction, 72, 101202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.04.003

Lim, W. M. (2024). What is qualitative research? An overview and guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal, 33(2), 199–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/14413582241264619

Mangaroska, K., & Giannakos, M. (2018). Learning analytics for learning design: A systematic literature review of analytics-driven design to enhance learning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 12(4), 516–534. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2018.2868673

Merriam, S. B., & Grenier, R. S. (Eds.). (2019). Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Modise, M. P., & Mudau, P. K. (2023). Using ePortfolios for meaningful teaching and learning in distance education in developing countries: A systematic review. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 71(3), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2022.2067731

Modise, M. P., & Vaughan, N. (2024). ePortfolios: A 360-degree approach to assessment in teacher education. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 50(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28579

Modise, M. P. (2021). Postgraduate students’ perception of the use of ePortfolios as a teaching tool to support their learning in an open and distance education institution. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.508\

Moore, R. L., Lee, S. S., Pate, A. T., & Wilson, A. J. (2025). Systematic review of digital microcredentials: Trends in assessment and delivery. Distance Education, 46(1), 8–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2024.2441263

Mougiakou, S., Vinatsella, D., Sampson, D., Papamitsiou, Z., Giannakos, M., & Ifenthaler, D. (2023). Educational data analytics for teachers and school leaders. Springer Nature.

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research. (1979). The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html

Nicholas, M., Paatsch, L., & Nolan, A. (2018). Using video-stimulated interviews to foster reflection, agency and knowledge-building in research. In L. A. Xu (Ed.), Video-based research in education: Cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 213–226). Routledge.

Open University. (n.d.). OU Analyse [Learning analytics dashboard]. Knowledge Media Institute. https://analyse.kmi.open.ac.uk/#dashboard

Pospíšilová, L., & Rohlíková, L. (2023). Reforming higher education with ePortfolio implementation, enhanced by learning analytics. Computers in Human Behavior, 138, 107449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107449

Rienties, B., Nguyen, Q., Holmes, W., & Reedy, K. (2017). A review of ten years of implementation and research in aligning learning design with learning analytics at the Open University UK. Interaction Design and Architecture(s), 33, 134–154. http://www.mifav.uniroma2.it/inevent/events/idea2010/doc/33_7.pdf

Rizvi, S., Rienties, B., Rogaten, J., & Kizilcec, R. F. (2024). Are MOOC learning designs culturally inclusive (enough)? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(6), 2496–2512. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12883

Stefaniak, J., Xu, M., & Yang, F. (2025). A scoping review to explore how decision-making is discussed in the field of learning design. TechTrends, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-025-01053-5

Steyn, S. (2024). Currere from Apartheid to Inclusion: Building culturally responsive pedagogies in post-apartheid South Africa. Taylor & Francis.

Sun, W., Schumacher, C., Chen, L., & Pinkwart, N. (2021). What do MOOC dashboards present to learners? An analysis from a Community of Inquiry perspective. In M. I. Sahin (Ed.), Visualizations and dashboards for learning analytics. Advances in analytics for learning and teaching (pp. 117–148). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81222-5_6

AUTHOR

Mashite Tshidi is a New Generation of Academics Programme (nGAP) Lecturer in the Department of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. He is also completing his PhD in Education, where his doctoral research investigates how learning analytics and personalised teaching approaches can enhance student engagement and outcomes in South African higher education. His research interests span programming education, learning analytics, and artificial intelligence, with a focus on improving student engagement and equity in digital education. Tshidi has authored and co-authored publications on generative artificial intelligence for teacher preparation, programming education in township schools, and the use of learning analytics to support student learning. His work reflects a commitment to inclusive and contextually relevant digital pedagogies in South Africa.

Email: mashite.tshidi@up.ac.za