23 “An Artifact of Learning We Could Be Proud of”: Guidelines and Insights on Implementing ePortfolios in Teacher Education

Mohammed Estaiteyeh

Brock University, Canada

ABSTRACT

The teacher education program at Brock University, Canada, has recently adopted ePortfolios as a learning and assessment tool for teacher candidates (TCs). Using a case study research design, the author shares 10 principles and practical guidelines on how ePortfolios can be introduced and implemented in teacher education programs. Additionally, reflections from TCs’ surveys are presented to examine their experiences in developing ePortfolios as part of the digital technologies course. Findings showed that TCs appreciated how the ePortfolio 1) was practical and relevant, especially for job interviews and their future careers; 2) advanced their technological skills; 3) allowed for creativity, autonomy, and reflection; 4) modelled an effective teaching and assessment strategy; and 5) was an engaging task. This chapter offers practical guidance to researchers and practitioners in teacher education by highlighting implementation and adoption experiences and presenting how ePortfolios can be used for pedagogical and assessment purposes. Broader implications for institutional change and digital equity are also discussed.

Keywords: ePortfolio, teacher education, digital pedagogy, assessment, digital technologies, student reflection

INTRODUCTION

ePortfolios have emerged as powerful platforms in pre-service teacher education programs, which has led to an increase in their adoption and implementation (Feder & Cramer, 2023). ePortfolios include a purposeful collection of teacher candidates’ (TCs’) work samples (e.g., videos, infographics, lesson plans), credentials, achievements, experiences, and reflective entries (Barrett, 2007; Chung & Jeong, 2024). One of the important features of ePortfolios is the workspace in which TCs record and reflect on their day-to-day learning. Another feature is the showcase in which TCs organize and present their learning at specific points in the process. This incremental documentation allows TCs to visualize the link between educational theories and pedagogical practices (Gulzar & Barrett, 2019).

Given the documented affordances and benefits of ePortfolios (Modise & Vaughan, 2024) and the increased demand on advanced TCs’ technological and pedagogical readiness (Estaiteyeh et al., 2024, 2025), the teacher education program at Brock University, Canada has recently adopted ePortfolios as a learning and assessment tool for TCs. Each TC starts developing their ePortfolio in the digital technology course early in the program. The ePortfolio consists of multiple assignments, each designed to highlight specific skills related to technology-infused lessons. TCs use the ePortfolio to demonstrate their understanding, application, and reflection on various aspects of educational technology covered in the course. Furthermore, TCs are encouraged to add their work from other courses throughout the teacher education program and to use the ePortfolio as a digital curriculum vitae. They also share the link to their ePortfolio with colleagues to build a professional network and a community of practice.

The digital technology course introducing ePortfolios to TCs is an online course that aims to prepare TCs for a technology-enhanced classroom. The course focuses on research-based strategies and concrete suggestions for effective integration of technologies in a way that enhances learning, with special emphasis on curriculum expectations of the Ontario Ministry of Education. In addition, the course provides opportunities for enhancing TCs’ personal skills with technology tools (Estaiteyeh et al., 2025).

By developing their ePortfolios, TCs will address multiple specific learning outcomes in this course. One of these objectives is establishing a professional identity and beginning to use digital tools that will build a positive digital footprint. The second objective is developing a repertoire of technology-enhanced activities that can be adapted for lessons across the Ontario Curriculum.

This chapter provides a practical guide on how ePortfolios can be introduced and implemented in teacher education programs. It explains how ePortfolios can serve a dual role as both a pedagogical strategy and an assessment tool. Additionally, it presents TCs’ reflections to explore their experiences in developing ePortfolios and perceptions of their benefits.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The section below details both the benefits and challenges of ePortfolios in teacher education. Moreover, using the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge (TPACK) framework (Koehler & Mishra, 2009) as a guiding conceptual lens, this section presents how ePortfolios can showcase and advance TCs’ digital and pedagogical competencies.

Benefits of ePortfolios in Teacher Education

ePortfolios feature many positive aspects, including providing frequent and targeted feedback to students, monitoring study habits, offering flexibility and enhancement of students’ work, facilitating collaboration, and being cost effective (Gugino, 2018). ePortfolios are also useful tools for TCs to document and reflect on their learning and teaching journey (Chye et al., 2019; Colás-Bravo et al., 2018; Hizli Alkan et al., 2024; Lam, 2024). Further, the benefits of ePortfolios in teacher education extend beyond the reflection component and allow TCs to enrich their cognitive learning strategies (Händel et al., 2020); critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Hussain & Al Saaidi, 2019); collaborative skills (Makokotlela, 2020); and socio-emotional, technological, and metacognitive knowledge (ElSayary & Mohebi, 2025). For instance, ePortfolios showcase professional teaching qualities such as teacher agency, sense of community, and teacher efficacy (Ho Younghusband, 2021).

Händel et al. (2020) explored the effect of using ePortfolios on exam performance of 1469 TCs. The ePortfolio in this study was used as a tool for students to reflect on their learning by using a journal, a to-do list, and a discussion forum. The results showed that TCs with the ePortfolio experience outperformed TCs who were not using the ePortfolios even when controlling for prior performance. The authors concluded that the strongest influence on the exam performance was the use of cognitive learning strategies that were aided by the ePortfolios. Beyond academic gains, ePortfolios were shown to increase creative imagination scores of students through blended experiential learning (Sitthimongkolchai et al., 2022). In harmony, Hussain and Al Saaidi (2019) concluded that designing an ePortfolio was shown to develop TCs’ design thinking, critical thinking skills, higher-order thinking, and creativity. Creativity was highlighted, especially in designing the layout, the cover page, and the contents.

Crisol Moya et al. (2021) explored the emotions that 358 students experienced upon using ePortfolios to manage their learning and assessment. Those students prevalently showed positive emotions. The emotions were ranked from strongest to weakest, with freedom being the strongest emotion, followed by motivation, curiosity, and inquiry being the weakest emotion. It was also shown that negative emotions, including disorientation and waste of time, were experienced less strongly by the students. This feeling of freedom and agency that TCs experience when creating and maintaining the ePortfolio was also highlighted by Ho Younghusband (2021). Ho Younghusband maintained that when TCs had the freedom to choose their artefacts, design a website, and personalize content, they were provided with a sense of agency, ownership, and pride. Likewise, Hizli Alkan et al. (2024) found that ePortfolios could be a valuable agentic and reflective pedagogical tool to scaffold learning. Hizli Alkan et al. revealed that the more the TCs were given autonomy of learning and flexibility to be creative in the ePortfolio development process, the more they benefited from the ePortfolio.

Finally, ElSayary and Mohebi (2025) showed that ePortfolios could positively influence TCs’ socio-emotional, technological, and metacognitive knowledge. For the socioemotional knowledge, TCs were interacting, collaborating, and working with their peers in different digital environments. With respect to metacognitive knowledge, TCs were planning and managing activities, evaluating and using information from various resources, collecting and analyzing data, identifying problems, and exploring alternative solutions. As for technological knowledge, TCs demonstrated responsibility and digital citizenship in selecting, using, and troubleshooting the appropriate technological applications to create their ePortfolios (ElSayary & Mohebi, 2025). This specific finding will be highlighted further in the next section.

ePortfolios, Teacher Candidates’ Digital Competence, and TPACK

Much of the literature on ePortfolios acknowledges their role in fostering TCs’ technological skills and digital competence (Hopper et al., 2018; Pegrum & Oakley, 2017; Stables, 2018). This lies in ePortfolios’ ability to familiarize TCs with effective technology integration strategies that they can use in their future classrooms (Gugino, 2018). The use of ePortfolios naturally entails much-needed technological skills, including hyperlinking, digitizing, embedding, digital storytelling, visually presenting, and publishing (Gulzar & Barrett, 2019). Therefore, using ePortfolios was shown to positively improve TCs’ technology integration ability (Chung & Jeong, 2024). ePortfolios also allow TCs to reflect on their current technology skills while learning to navigate new ones. In Chung and Jeong’s (2024) study, TCs showed increased confidence and proficiency in learning new technology applications and effectively integrating new technologies in their lessons. Also, using ePortfolios, TCs were able to strengthen their digital narratives with enhanced considerations and understanding of digital citizenship, digital footprint, and FIPPA guidelines (Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act), which are all important digital literacy skills (Ho Younghusband, 2021). In accordance, Gugino (2018) maintains that when TCs learn advanced technological skills, they are able to create more accessible text and collaborate with other teachers to support students with disabilities.

In addition to promoting TCs’ digital/technological competence, it is important to frame the use of ePortfolios within the broader skillset that future teachers must acquire. Specifically, ePortfolios must also showcase and contribute to TCs’ pedagogical and content knowledge. To align with this goal, the TPACK framework (Koehler & Mishra, 2009) is utilized as a guiding conceptual lens in this research. The TPACK framework highlights three core knowledge domains: technological knowledge, which is knowledge about software and hardware; pedagogical knowledge, which concerns how to manage, instruct, and guide students; and content knowledge, which is knowledge about the specific discipline or subject matter. The framework also emphasizes the intersections between these domains to enhance technology integration in teaching and learning (Rosenberg & Koehler, 2015; Wang et al., 2018).

Overall, the literature has shown that ePortfolios are promising tools in teacher education. However, it is important to consider some challenges that accompany the use of ePortfolios as well as recommended practices to mitigate those challenges.

Challenges and Recommended Practices

Identifying and understanding challenges to adopting ePortfolios is crucial to guide future research and improve implementation. First, Chye et al. (2019) highlighted that ePortfolios may be limited in advancing TCs’ reflective practice. For instance, TCs felt that showcasing their work was contradictory to the intrinsic value of reflection, as it was forcing TCs to cherry-pick their best work rather than authentically including both their strengths and weaknesses. However, mitigating this challenge can be supported by effective communication of the ePortfolio rationale as well as using purposeful and practical tasks instead of only presenting the best work (Hizli Alkan et al., 2024).

Another challenge to implementing ePortfolios is when the process is viewed as superficial scrapbooking rather than a meaningful learning experience (Vaughan et al., 2017). In this scenario, TCs would view the ePortfolio as merely a storage space for their assignments (Chye et al., 2019). Babaee et al. (2021) demonstrated that TCs who showed higher-level conceptions of ePortfolios reported higher quality of teaching, clarity of goals, and understanding of workloads and assessment. Thus, students must understand the role of the ePortfolios in reflecting, revising their ideas, and conceptual change to improve their understanding.

Third, Lam (2024) emphasized the importance of not taking for granted students’ skills in creating digital artefacts. Students need to know how to compile, select, and validate their artefacts to improve their learning. Similarly, Totter and Wyss (2019) concluded that it takes students time and training to get used to working with ePortfolios. This element must be taken into consideration, and the software must be chosen carefully to align with the planned activities. Thus, it is important to use the ePortfolios over a longer time and across different subject areas in the teacher education program (Vaughan et al., 2017).

Walland and Shaw (2022) distinguish between the use of ePortfolios as formative and summative assessment tools. As formative assessment tools, ePortfolios are process-oriented and can capture a learner’s journey. This use gives flexibility for ideas and skills to develop over time. Importantly, the instructor must explicitly communicate with TCs what skills are being addressed and monitored in each task, such as creativity and technological literacy. On the other hand, when ePortfolios are used as summative assessment tools, it is recommended that TCs are given a highly prescribed task to accomplish. This can be done using detailed assignment rubrics, task exemplars, and teachers’ support and scaffolding.

Finally, regarding successful institutional implementation of ePortfolios, Gulzar and Barrett (2019) recommend useful strategies, including 1) ensuring access to computers and software; 2) incentivizing both teachers and students; 3) setting a clear vision and rationale for the ePortfolios from the beginning; and 4) training and skill development, such as basic technology skills, collecting, digitizing, selecting, organizing, reflecting, goal setting, and presenting. For instructors, helpful strategies include facilitating the portfolio processes, providing feedback, providing information on formative and summative assessments, identifying useful technology resources, and offering support.

METHODOLOGY

This research adopts a case study design (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Yin, 2014). Case studies answer the “how” and “why” questions and portray the characteristics of real-life events and organizational processes (Yin, 2014). This is used to document the process of introducing ePortfolios in teacher education programs and implementing them within the digital technology course. This method also allows for exploring the different uses of ePortfolios and how TCs perceive their benefits.

Data Sources

This chapter includes data from three different sources. First, the author adopts a narrative approach (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015) to detail the steps of introducing and implementing ePortfolios in the teacher education program. Second, samples of TCs’ ePortfolios are presented to highlight their significant work. Third, the author presents findings of an online Qualtrics survey administered to TCs following the completion of the digital technology course in which the ePortfolio was implemented. The survey included 43 Likert scale items and five open ended questions, which were adapted from Estaiteyeh et al.’s (2024) survey on TCs’ TPACK development. However, only the questions relevant to the ePortfolio task are reported on in this chapter, specifically two Likert scale item questions and one open-ended question. These questions were revised based on the nature of the ePortfolio assignment and the literature. The Likert scale questions are

- Rate your familiarity with and competence in website creation in your teaching (1-unfamiliar with & incompetent in using; 2-familiar with but incompetent in using; 3-familiar with & competent in using).

- Indicate the value or the benefit of the ePortfolio in terms of preparing you to use educational technologies (1-inadequate; 2-average; 3-excellent)

Additionally, the open-ended question is: Reflect on your experiences creating your ePortfolio. How effective and beneficial has this task been?

Author’s Positionality and Study Participants

The author is the team lead for the digital technology course presented in this research. As part of the course development, the team lead developed the ePortfolio assignment. As for the survey, participants are 214 TCs (79 TCs in the Intermediate/Senior division and 135 TCs in the Primary/Junior/Intermediate division). Those TCs were enrolled in multiple sections of the digital technology course during the academic year 2024-2025. Ethical approval was obtained from the Brock University Ethics Board, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data from the Likert scale items were analyzed using descriptive statistics on MS Excel. Qualitative data obtained from the open-ended question were analyzed through manual thematic coding to provide an in-depth analysis of the responses of TCs. The analysis was performed as an inductive process in which initial codes were developed based on the frequency of words in students’ responses. Thereafter, the researcher grouped similar codes into themes, finalized them, and interpreted the themes to draw conclusions (Gall et al., 2005). Afterwards, the researcher calculated the frequency of responses in relation to each theme.

Limitations

Despite the triangulation of data sources (author’s narrative, TCs’ work, and survey data), a few limitations exist. First, the author reports on survey responses following one course, which limits the duration of interaction with participants. Additionally, the author relies on self-reported data by TCs in the survey to explore their reflections and experiences. These limitations may impact the validity and generalizability of the findings. Hence, further longitudinal research is recommended to explore TCs’ use of the ePortfolios beyond the digital technology course and the value of the ePortfolio after the completion of the teacher education program.

RESULTS

Implementation Details

The digital technology course in the teacher education program addresses both TCs’ technological and pedagogical skills. It is also offered early in the two-year program. Accordingly, this course is the most suitable to incorporate the task of developing the ePortfolio.

In the first week of the course, TCs are provided with a document that details the ePortfolio assignment (the document is available for sharing upon request from the author). This document provides TCs with the rationale behind developing ePortfolios and presents the technical steps and resources that TCs will need to start their work. The first two weeks in the course provide TCs with foundational and technical skills to create their website (creating pages and subpages, inserting multimedia, hyperlinking, etc.). TCs also get introduced to digital design and publishing skills in reference to Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) guidelines. As part of building the ePortfolio, TCs are asked to create an introductory page, a resume page, a teaching philosophy page, and a page to describe their ongoing professional development. While these pages are not directly related to the course content, creating these pages highlights the usage of the ePortfolio beyond this course and makes it easier for TCs to continue working on the ePortfolio after the course ends.

As TCs progress in the course content, they use the ePortfolio as a platform to incorporate their coursework on a weekly basis. As such, TCs use the ePortfolio as a learning and assessment tool. By the end of the course, TCs will have all their coursework in one place, showcasing their experiences, skills, and growth. To support scaffolding, TCs are given the opportunity to revise their submissions after they receive the instructor’s feedback. The availability of each TC’s work in one place also facilitates peer feedback and sharing of resources among TCs. This exemplifies how the ePortfolio is used for learning and as learning takes place.

The choice of Google Sites as the platform for the ePortfolio is mainly due to the fact that it is an open-access and user-friendly tool. TCs can make use of easy accessibility, sharing, and updating content. Additionally, Google Sites provides different access options. TCs may choose to restrict access to certain documents to the instructor only or a few colleagues who have the URL link. Otherwise, they may also have their website publicly available on search engines. It is also important to note that unifying the platform is helpful as instructors provide technical instructions to TCs during class time, which is relatively limited. Once TCs master the basic skills, they can shift to another platform if they wish to.

Following the introduction of ePortfolios and their implementation in the digital technology course, the author tried to promote their adoption at the level of the teacher education program. The author encouraged other team leads to use the ePortfolio in their courses by presenting the rationale and the details of this assignment at one of the program meetings. The author also presented a few sample TCs’ ePortfolios and explained how TCs could add more pages for other courses. The objective behind such adoption was to maximize TCs’ use of this platform in showcasing their work, ensure variety in represented materials, and increase their familiarity with available tools and features of the ePortfolio. Several team leads expressed interest in hosting their assignments on the ePortfolio and encouraging their students to use it to showcase their respective coursework. One advantage is that TCs will have already been introduced to the technicalities of creating the website and would require minimal technical support.

TCs’ Sample Work

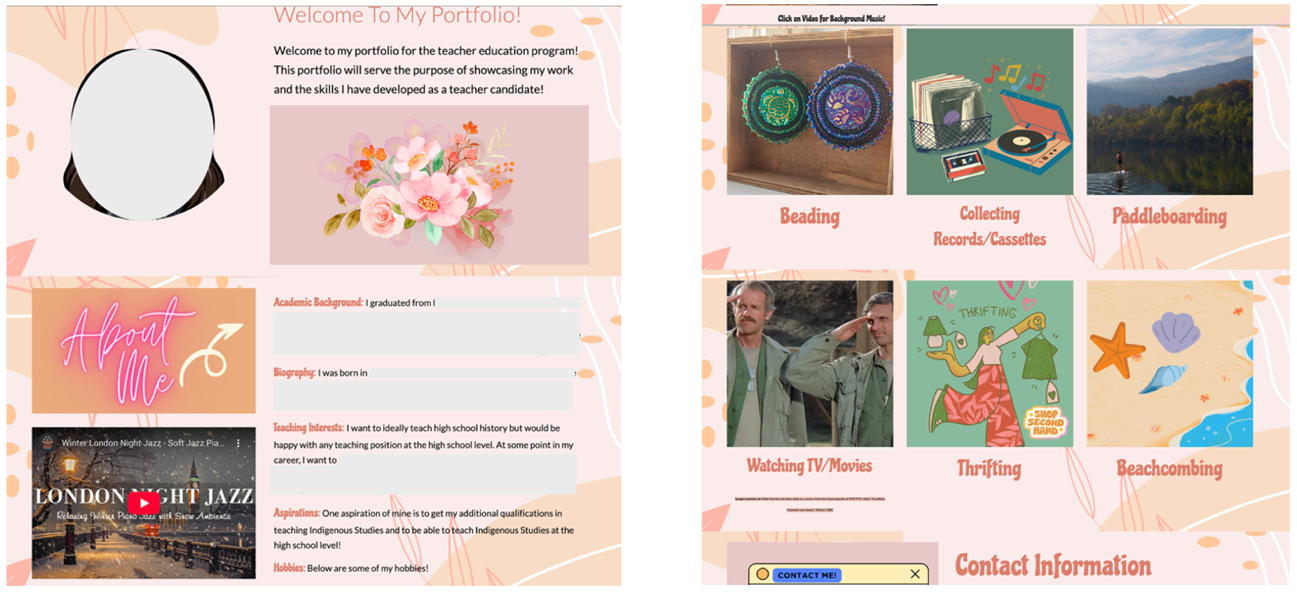

This section presents sample work created by the TCs as included in their ePortfolios. Figure 1 shows a portion of the ePortfolio Homepage used to introduce each TC and present their academic background, interests, hobbies, aspirations, and contact information. This sample shows a high level of creativity in the page design and the use of multimedia (pictures and videos) to enhance multimodal representation and increase viewer engagement. The TC personal photograph/bitmoji is blurred for anonymity.

Figure 1

A portion of the ePortfolio homepage

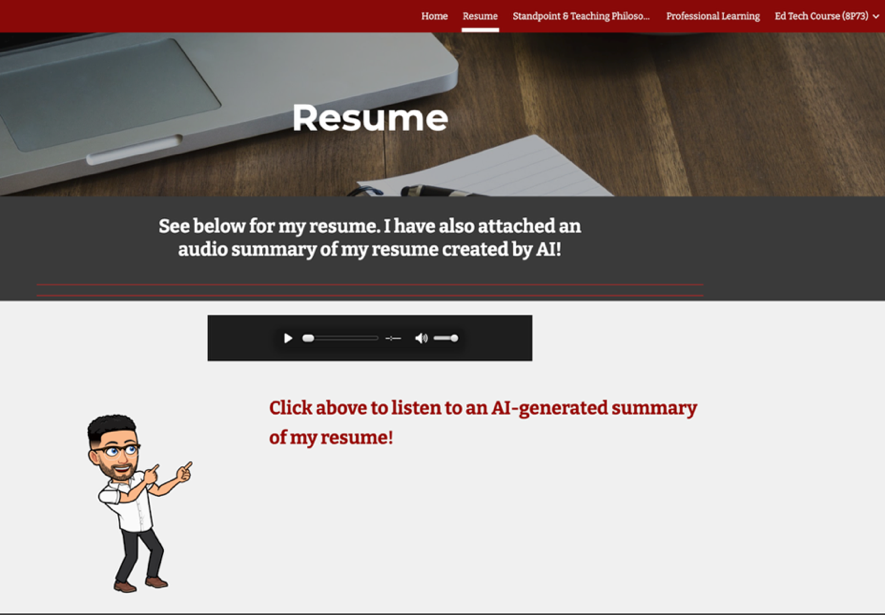

Figure 2 shows the Resume section in which TCs include their CV, detailing their academic background, work experience, and major achievements. As shown in Figure 2, some TCs incorporated creative ideas such as AI-generated podcasts to present their resume in addition to the text-based document (retracted for anonymity). Additionally, Figure 3 shows a sample Teaching Philosophy/Standpoint section in which TCs explained their teaching principles and approaches.

Figure 2

The resume section of the ePortfolio

Figure 3

A portion of the teaching philosophy section within the ePortfolio

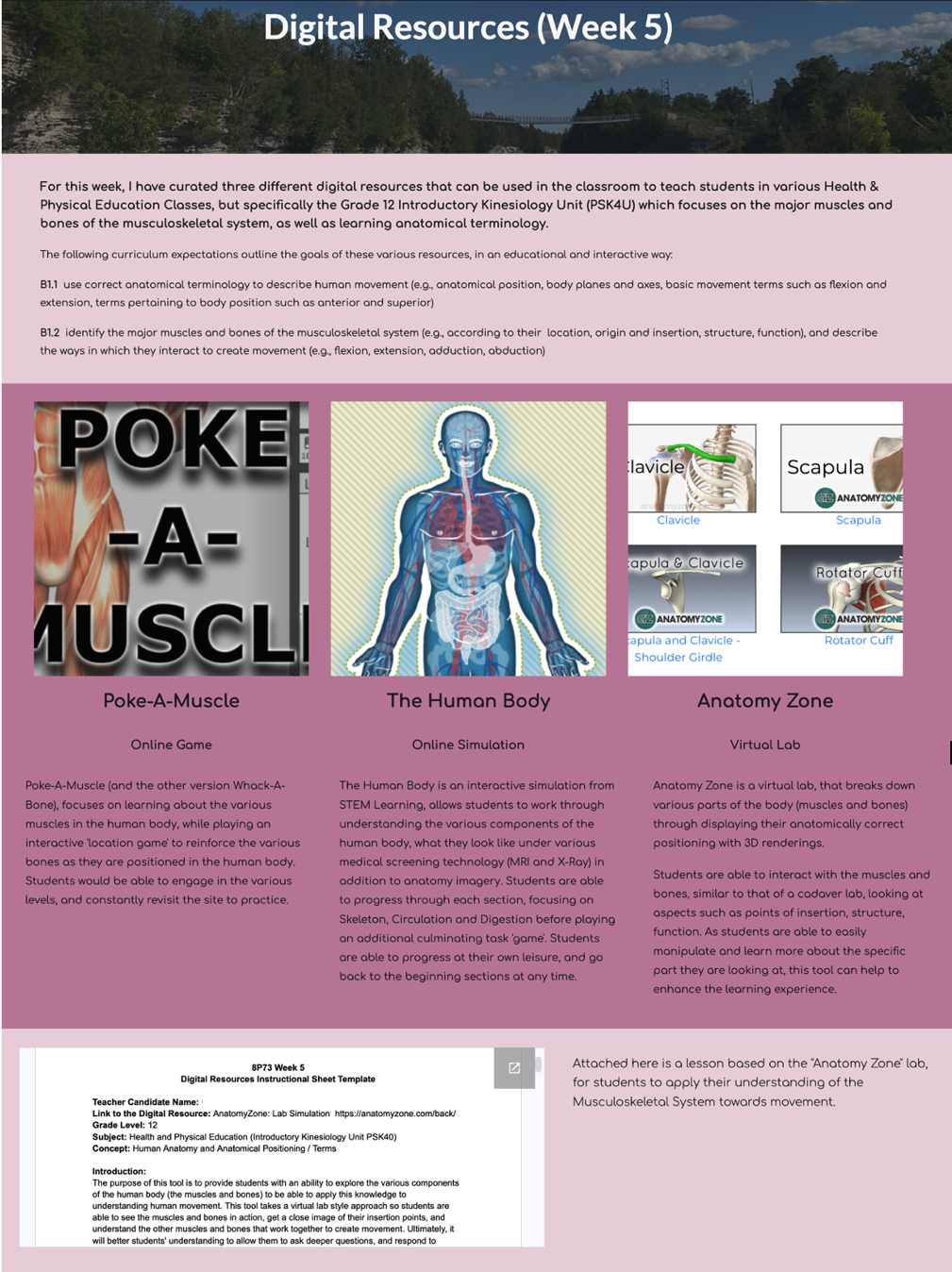

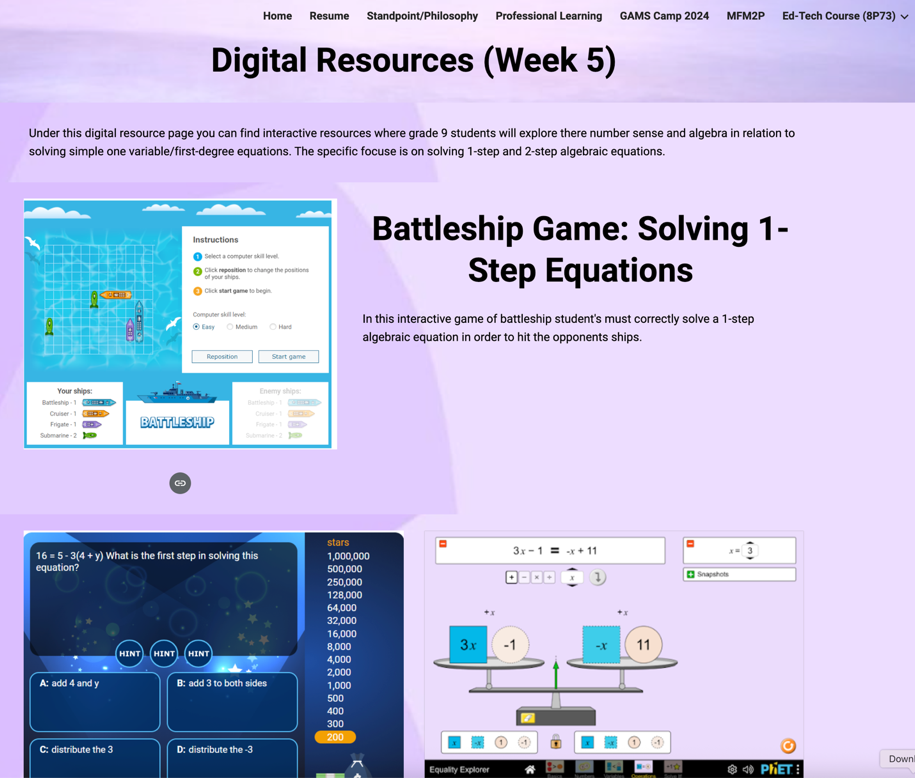

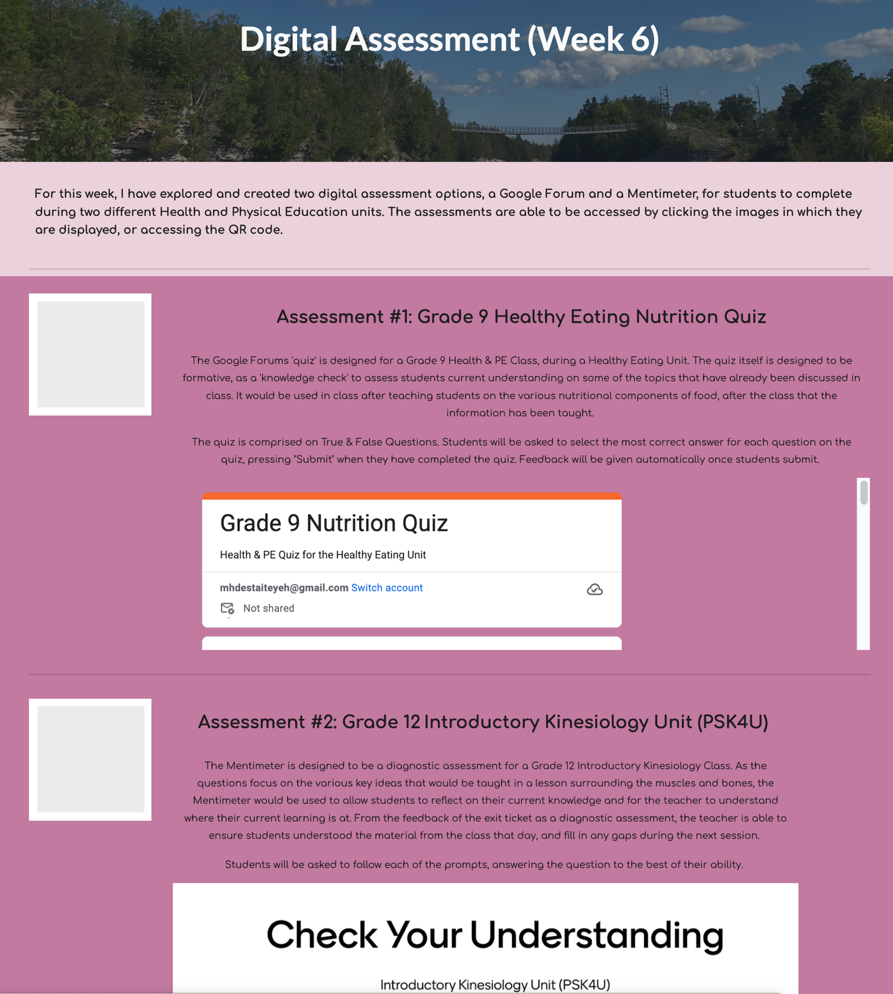

Figures 4, 5, and 6 show samples of TCs’ work on the sections related to digital teaching resources and digital assessment tools as part of their digital technology coursework. These are core lessons and assignments in this course in which TCs create and curate multimedia and virtual resources specific to their teachable subjects. TCs also justify their choices, explain their pedagogical reasoning, and provide details on how they would use these resources using an instructional sheet (template provided by the instructor).

Figure 4

A portion of the digital resources section within the ePortfolio

Figure 5

A portion of the digital resources section within the ePortfolio

Figure 6

A portion of the digital assessment section within the ePortfolio

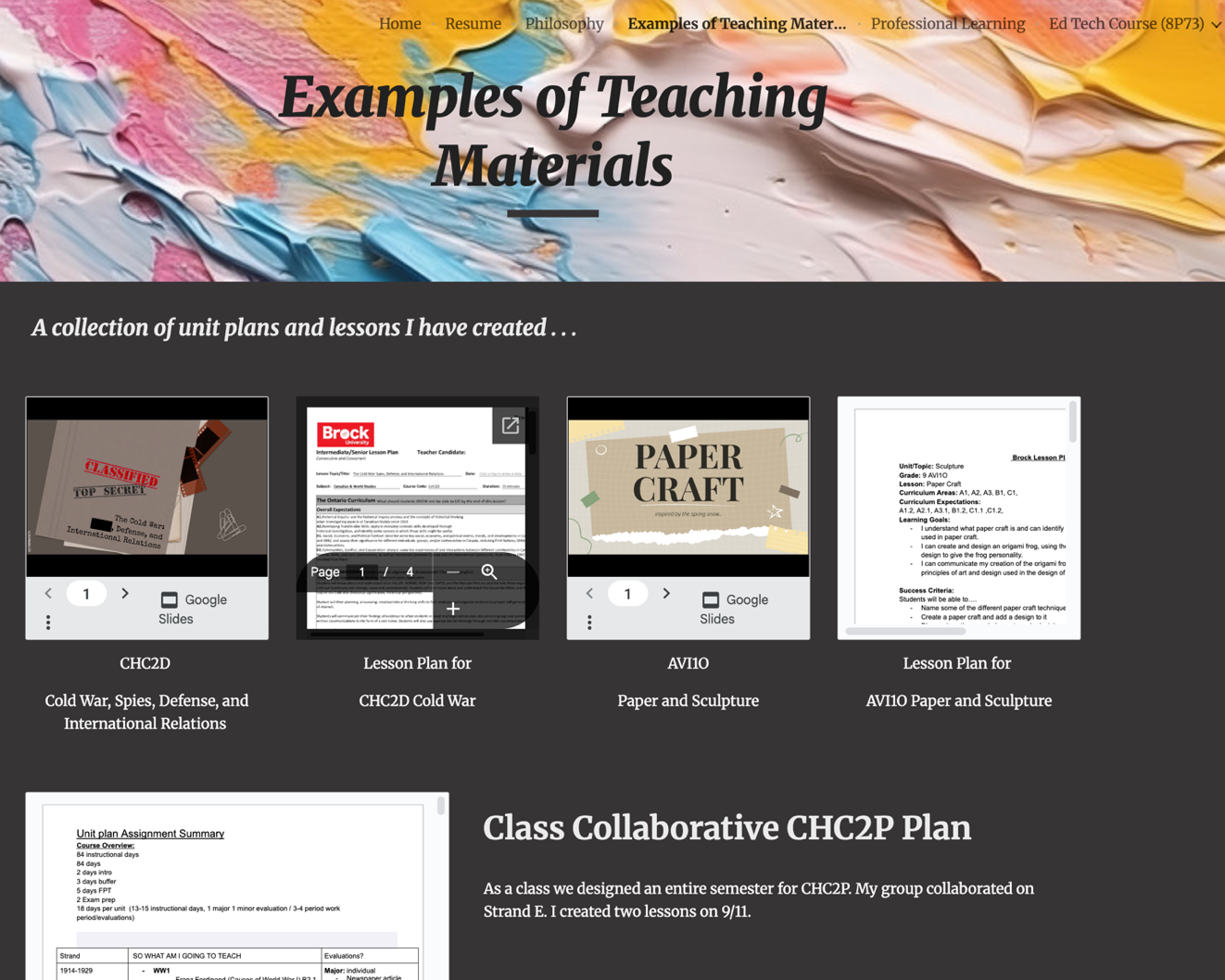

Finally, it is important to note that several TCs started using the ePortfolio throughout and after the digital technology course to showcase their work from other courses (Figure 7). Some TCs included sample lesson plans, unit plans, and presentations. Others included reflections and daily journals from their school placements.

Figure 7

A section on teaching materials within the ePortfolio based on other courses

TCs’ Insights

TCs’ survey responses showed overwhelmingly positive ratings following the ePortfolio assignment. First, on the item related to their familiarity with and competence in website creation, 85% of TCs indicated they were both familiar and competent, 13% indicated that they were familiar but incompetent, and only 2% indicated that they were still unfamiliar and incompetent in using website creation. As for the value or the benefit of the ePortfolio in preparing them to use educational technologies, 82% indicated ePortfolios had an excellent value, 17% indicated that they had an average value, and only 1% indicated that they had an inadequate value.

TCs’ open-ended responses reiterated their positive reflections on their experiences creating the ePortfolio. TCs responded to the question on how effective and beneficial this task has been. Several themes emerged as a result of the inductive data analysis. These themes were 1) the practical and relevant nature of the ePortfolio, especially for a job interview (30 TCs); 2) advancing their technological skills (24 TCs); 3) allowing for creativity, autonomy, and reflection (7 TCs); 4) the ePortfolio as a learning and assessment strategy (5 TCs); and 5) the engaging nature of this task (5 TCs).

First, most respondents mentioned that the ePortfolio was a practical and relevant assignment. For instance, some TCs pointed to the ePortfolio as a tool they can use with their future students and for themselves as teachers in the future upon using the curated resources. TCs said:

Reflecting on my experiences creating an ePortfolio, I found it to be incredibly beneficial and effective in different ways. Creating my ePortfolio provided me with a valuable opportunity to showcase my skills, experiences, and achievements in a digital format. By compiling various artifacts, including projects, papers, and presentations, I was able to demonstrate my growth and development over time.

I want to use the website to create a review page for my tutoring services. I also want to continue adding to my website when I am an educator on external resources like games and things that I believe will help my students further their learning.

TCs also highlighted its benefit in hosting their coursework and showcasing their skills. They specifically mentioned that the ePortfolio would be useful for them as job seekers in the interview phase:

I think the digital portfolio will be an excellent resource to show future employers and other educators about my skills and ability to use technology.

Some TCs stated that they were using the ePortfolio in other courses, thereby reiterating its relevance and benefit:

I decided to use my Google Site to incorporate all of my courses into the platform for this class. I found it useful to have all of my resources and information in one place.

Second, TCs highlighted the positive impact of the ePortfolio on their technological skills such as creating websites, embedding content, and digital publishing. Some of them highlighted that this familiarity with technological tools would be helpful in the future. TCs said:

I now know what it looks like to develop a classroom website. I also learned of ideas that I had not considered, such as embedding content into website rather than just adding links, etc.

I was forced to explore different tech tools and websites and learn how they can interact with one another. The ePortfolio was great because I practised changing digital layouts and organization.

After learning how to create the website, I got excited and hopeful. I loved creating and adding new links and resources that explained myself and the type of teacher I wanted to be. It gave me a skill that I will use plenty in the future.

Third, TCs discussed how the ePortfolio advanced their personal skills such as creativity, autonomy, organization, communication, and reflection. They said:

I enjoyed the task because it allowed for each of us to take our own path creatively on what we wanted to do, what topics we wanted to cover, our assessments, etc. I liked how we had the creative direction.

The process of reflecting on each artifact allowed me to gain deeper insights into my learning journey and identify areas for future growth. Presenting my ePortfolio to others also helped me refine my communication skills and articulate my strengths and accomplishments.

Fourth, some TCs concluded how the ePortfolio modeled an effective teaching and assessment strategy that promoted their learning. Some linked this work to theories in educational technology such as TPACK. They said:

The first session provided the framework and context for the scope and applicability. The instructional sheets, citations, and preambles in our ePortfolio help to ground our work in practical, instructional contexts.

The ePortfolio was good practice and a clever idea, getting us to frame our coursework in site-making software that we can also use as teachers.

TPACK is a really useful framework I had never heard of before, and it came into play with both the portfolio and the (other course) assignment.

Fifth, several TCs highlighted the engaging and creative nature of this assignment. They emphasized their pride in what they were able to achieve. TCs said:

I enjoyed creating the ePortfolio, and I am proud of the work I have done.

These tasks were really beneficial to my understanding of using Ed Tech—and they were enjoyable and creative tasks as well.

Finally, despite these reported affordances and benefits of ePortfolios, it is important to note a few challenges or mixed feelings that some TCs expressed. Some TCs did not believe they could make future use of it. Others mentioned facing technical difficulties or their need for advanced technological skills to produce better work. TCs said:

The ePortfolio was cool, but really I didn’t put enough work into it to actually use it after the course. Cool to have but not practical; I doubt ANYONE will use it professionally.

Despite the frustrations of navigating new systems, the ePortfolio proved to be practical and beneficial.

These tasks were somewhat difficult for not being familiar with them in the beginning, but as time went on, I felt much more comfortable and confident in my abilities.

TCs’ feedback was insightful, as it contributed to improving the assignment in the subsequent academic year. For instance, several TCs shed light on technical skills they lacked prior to developing their ePortfolios. This insight led the instructional team to give more time to cover the basic technological skills in the first two weeks of the course to ensure that those students are not disadvantaged. Scaffolding was also ensured by providing general feedback to all TCs in class, highlighting common mistakes and good practices, in addition to the individualized feedback they received on their assignments. Further, based on TCs’ questions and clarifications each week, the author revised the assignment description and assessment criteria to ensure that important details are provided to students in the assignment document.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This chapter provided a practical guide on how ePortfolios were introduced and implemented using a case study of the teacher education program at Brock University. It explored how ePortfolios can serve a dual role as both a pedagogical strategy and an assessment tool, especially in digital technology courses.

Guidelines for Implementing an ePortfolio Assignment in Teacher Education

Based on the presented case, the author shares a consolidated set of 10 principles and practical guidelines for educators who wish to adopt the ePortfolio assignment in their own courses or at the level of teacher education programs:

Choose the right course for implementation: Select a course that introduces foundational digital and pedagogical skills early in the program. Also ensure that the course provides both technical instruction and pedagogical context for technology integration. TCs’ reflections showed that it was the first time for many of them to create a website and that the ePortfolio assignment contributed to their digital and pedagogical competencies. Thus, digital technology courses are well-suited for initiating the implementation of ePortfolios in teacher education programs, particularly because they are designed to model the TPACK framework and develop TCs’ technological and pedagogical skills.

Clearly define and communicate the purpose and value of the ePortfolio: Position the ePortfolio as more than a course assignment. Present it as a digital CV and a tool for lifelong professional growth. Also explain to TCs how it supports documentation of learning, reflection, and community building. In fact, TCs in this study appreciated how the ePortfolio was practical, relevant, and useful for them as job seekers. This guideline is in accordance with Vaughan et al.’s (2017) framing of the ePortfolio as a comprehensive meaningful learning experience.

Use an accessible and unified platform: Adopt a user-friendly, open-access tool like Google Sites to minimize technical barriers. Standardize the platform to simplify instruction and technical support during class time. Still, allow students to personalize or migrate to another platform once foundational skills are established.

Scaffold technical and pedagogical skills: Begin with sessions on website creation, digital publishing, and accessibility (e.g., UDL, AODA). Provide hands-on support during the initial weeks to build students’ confidence. Also share curated resources and tutorials for independent learning.

Offer clear technical instructions: Provide a step-by-step guide with visuals and examples. Include instructions on publishing, privacy settings, and accessibility checks. Remind students to regularly publish updates and test all links. Principles 3, 4, and 5 are aligned with prior research recommendations on setting and communicating a clear vision and rationale for the ePortfolios from the beginning, offering training and skill development to TCs, ensuring access to computers and software, and supporting course instructors as they introduce this assignment (Gulzar & Barrett, 2019; Lam, 2024; Totter & Wyss, 2019). Clarifying, scaffolding, and pacing the required tasks can help minimize TCs’ challenges and maximize the benefits from the ePortfolios.

Design a modular, expandable structure: Require initial pages such as a homepage, resume, teaching philosophy, professional learning, and course-specific pages for weekly content. Also encourage students to add new pages for work from other courses throughout the program.

Integrate the ePortfolio throughout the course: Align weekly coursework with portfolio updates. Use the ePortfolio for both formative feedback and summative assessment. Also provide opportunities for students to revise their work after receiving the instructor’s feedback. In line with principles 6 and 7, TCs’ reflections demonstrated how the ePortfolio served a dual role as a learning and assessment strategy. These guidelines also echo Walland and Shaw’s (2022) insight that ePortfolios can be used as formative and summative assessment tools and that instructors must explicitly communicate what skills are being addressed in each task.

Foster peer collaboration and feedback: Leverage the shared access feature to encourage students to view, reflect on, and comment on each other’s work. Promote a community of practice by encouraging portfolio sharing and resource exchange. In reflecting on the ePortfolio assignment, several TCs indicated how it afforded creativity, autonomy, and reflection. This feedback reiterates the documented positive impacts of ePortfolios on students’ reflective practice, metacognitive knowledge, collaborative skills, and sense of community (ElSayary & Mohebi, 2025; Ho Younghusband, 2021; Makokotlela, 2020).

Advocate for program-wide adoption: Share the rationale and benefits of the ePortfolio with colleagues. Present successful examples to demonstrate feasibility and impact. Also encourage other instructors to align their assignments with the ePortfolio to ensure continuity and maximize value.

Encourage long-term use: Remind students that the ePortfolio is an evolving professional tool, not just a one-time task. Promote its use for job applications, reflection, and professional networking beyond the program. Consistent with the latter two principles, several TCs started using the ePortfolio throughout and after the digital technology course to showcase their work from other courses and school placements. This illustrates how program-level adoption and sustained use of ePortfolios can help TCs recognize their broader value beyond merely serving as a storage space for assignments (Babaee et al., 2021; Chye et al., 2019; Vaughan et al., 2017).

Teacher Candidates’ Experiences and Perceptions

TCs’ survey responses and reflections highlighted their overwhelmingly positive experiences in and perceptions toward the ePortfolio assignment. Reflections from TCs showed that they appreciated how the ePortfolio was practical and relevant, especially for job interviews and their future careers. TCs viewed the ePortfolios as a convenient platform to document and reflect on their learning and teaching journey (Chye et al., 2019; Colás-Bravo et al., 2018; Hizli Alkan et al., 2024; Lam, 2024). TCs also highlighted how the ePortfolios advanced their technological skills, which is in accordance with prior literature (e.g., Hopper et al., 2018; Pegrum & Oakley, 2017; Stables, 2018). Moreover, the impact of ePortfolios on TCs’ personal skills, such as creativity, autonomy, and reflective abilities, was an emerging theme in their responses. This finding is also consistent with the literature (e.g., Ho Younghusband, 2021; Sitthimongkolchai et al., 2022). TCs also reported on their high levels of engagement throughout the creation of the ePortfolio, reiterating Crisol Moya et al.’s (2021) findings on positive emotions associated with this task. Finally, it is important to highlight how TCs’ reflections and the assignment developer’s intentions were aligned in terms of using ePortfolios as both an instructional and assessment strategy. This is in accordance with the literature emphasizing the dual role of ePortfolios are both a pedagogical strategy (Hizli Alkan et al., 2024) and an assessment tool for formative and summative purposes (Walland & Shaw, 2022).

On the other hand, the benefit of TCs’ collaboration and resource sharing, although intended by the assignment developer and documented in the literature (e.g., Gugino, 2018), was not highly evident in TCs’ responses. This shortcoming requires more effort in the future to highlight this aspect for TCs and encourage them to maximize the use of their ePortfolios as a community of practice. Furthermore, the reported challenges by the TCs are in accordance with other scholars who pointed to the importance of training on digital skills and taking the time with TCs to familiarize them with ePortfolios (Lam, 2024; Totter & Wyss, 2019).

Implications

This research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the integration of digital technologies in teacher education, offering insights for program administrators, teacher educators, and educational researchers. It addresses several key themes explored in this book, including implementation and adoption experiences, the pedagogical and assessment potential of ePortfolios, and practical strategies for researchers and practitioners. Additionally, the implementation guidelines and accompanying resources provide concrete, actionable support for educators seeking to integrate ePortfolios into their courses. Collectively, these contributions aim to enhance the impact of ePortfolios within teacher education programs while fostering TCs’ professional growth, career readiness, and commitment to lifelong learning.

At an institutional level, successful ePortfolio adoption requires systematic change management approaches that address both technological infrastructure and cultural shifts in assessment practices. Program-wide commitment to ePortfolio integration begins with structured opportunities for TCs to develop their digital competencies and showcase their learning. Such commitment can serve as a catalyst for digital transformation and innovation in pedagogy. However, this transformation requires comprehensive support systems that include technical resources, professional development opportunities, and clear policies for ePortfolio integration across courses. The effective use of ePortfolios necessitates ongoing professional development for teacher educators themselves, who must develop new competencies in digital pedagogy, online assessment strategies, and mentoring practices, pointing to the need for institutional investment in faculty development programs that support educators’ transition to digital portfolio-based approaches. Finally, the research highlights important considerations for digital equity by accounting for varying levels of technological access and digital literacy among TCs, thereby ensuring that ePortfolios create opportunities rather than barriers for students from marginalized populations.

REFERENCES

Babaee, M., Swabey, K., & Prosser, M. (2021). The role of e-portfolios in higher education: The experience of pre-service teachers. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 37(4), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2021.1965508

Barrett, H. C. (2007). Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: The REFLECT initiative. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(6), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.50.6.2

Chung, J.-Y., & Jeong, S.-H. (2024). Korean pre-service teachers’ experiences of creating an online teaching portfolio in the teacher preparation course. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 14(2), 1. https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2024-0021

Chye, S., Zhou, M., Koh, C., & Liu, W. C. (2019). Using e-portfolios to facilitate reflection: Insights from an activity theoretical analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.06.002

Colás-Bravo, P., Magnoler, P., & Conde-Jiménez, J. (2018). Identification of levels of sustainable consciousness of teachers in training through an e-portfolio. Sustainability, 10(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103700

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

Crisol Moya, E., Gámiz Sánchez, V., & Romero López, M. A. (2021). University students’ emotions when using e-portfolios in virtual education environments. Sustainability, 13(12), Article 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126973

ElSayary, A., & Mohebi, L. (2025). Fostering preservice teachers socio-emotional, technological, and metacognitive knowledge (STM-K) using e-portfolios. Education and Information Technologies, 30(2), 2095–2122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12894-7

Estaiteyeh, M., DeCoito, I., & Takkouch, M. (2024). STEM teacher candidates’ preparation for online teaching: Promoting technological and pedagogical knowledge. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 50(4). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28594

Estaiteyeh, M., Heenan, J., & Sovegjarto, B. (2025). Listening to teacher candidates and teacher educators: Revising educational technology courses in a Canadian teacher education program. Education Sciences, 15(6), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060730

Feder, L., & and Cramer, C. (2023). Research on portfolios in teacher education: A systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2023.2212870

Gall, J. P., Gall, M. D., & Borg, W. R. (2005). Applying educational research: A practical guide (5th ed.). Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Gugino, J. (2018). Using Google Docs to enhance the teacher work sample: Building e-portfolios for learning and practice. Journal of Special Education Technology, 33(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643417729135

Gulzar, N., & Barrett, H. C. (2019). Implementing ePortfolios in teacher education: Research, issues and strategies. In S. Walsh & S. Mann (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English language teacher education (pp. 488–506). Routledge.

Händel, M., Wimmer, B., & Ziegler, A. (2020). E-portfolio use and its effects on exam performance—A field study. Studies in Higher Education, 45(2), 258–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1510388

Hizli Alkan, S., Bradfield, K., & and Fraser, S. (2024). Prospective teachers’ views and experiences with e-portfolios. Reflective Practice, 25(6), 767–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2024.2398800

Ho Younghusband, C. (2021). E-portfolios and exploring one’s identity in teacher education. The Open/Technology in Education, Society, and Scholarship Association Journal, 1(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.18357/otessaj.2021.1.2.20

Hopper, T., Fu, H., Sanford, K., & Monk, D. (2018). What is a digital electronic portfolio in teacher education? A case study of instructors’ and students’ enabling insights on the electronic portfolio process. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 44(2). https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt27634

Hussain, R. M., & Al Saadi, K. K. (2019). Students as designers of E-book for authentic assessment. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 16. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2019.16.1.2

Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9(1), 60–70. https://citejournal.org/volume-9/issue-1-09/general/what-is-technological-pedagogicalcontent-knowledge/

Lam, R. (2024). Understanding the usefulness of e-portfolios: Linking artefacts, reflection, and validation. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 62(2), 405–428. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2022-0052

Makokotlela, M. V. (2020). An e-portfolio as an assessment strategy in an open distance learning context: International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 16(4), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.2020100109

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Pegrum, M., & Oakley, G. (2017). The changing landscape of e-portfolios: Reflections on 5 years of implementing e-portfolios in pre-service teacher education. In T. Chaudhuri & B. Cabau (Eds.), E-portfolios in higher dducation: A multidisciplinary approach (pp. 21–34). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3803-7_2

Modise, M.P., & Vaughan, N. (2024). ePortfolios: A 360-degree approach to assessment in teacher education. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 50(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.21432/cjlt28579

Rosenberg, J. M., & Koehler, M. J. (2015). Context and technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): A systematic review. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 47(3), 186–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2015.1052663

Sitthimongkolchai, N., Viriyavejakul, C., & Tuntiwongwanich, S. (2022). Blended experiential learning with e-portfolios learning to enhance creative imagination. Emerging Science Journal, 6. https://doi.org/10.28991/ESJ-2022-SIED-03

Stables, K. (2018). Use of portfolios for assessment in design and technology education. In M. J. de Vries (Ed.), Handbook of technology education (pp. 749–763). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44687-5

Totter, A., & Wyss, C. (2019). Opportunities and challenges of e-portfolios in teacher education. Lessons learnt. Research on Education and Media, 11(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.2478/rem-2019-0010

Vaughan, N. D., Cool, R., MacIsaac, K., & Stogre, T. (2017). ePortfolios as over-arching high impact practices for degree programs. The AAEEBL ePortfolio Review, 1(3), 36-45.

Walland, E., & Shaw, S. (2022). E-portfolios in teaching, learning and assessment: Tensions in theory and praxis. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2022.2074087

Wang, W., Schmidt-Crawford, D., & Jin, Y. (2018). Preservice teachers’ TPACK development: A review of literature. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 34(4), 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2018.1498039

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

AUTHOR

Dr. Mohammed Estaiteyeh is an Assistant Professor of Digital Pedagogies and Technology Literacies in the Faculty of Education at Brock University, Canada. He is also the subject team leader for digital technology courses in the teacher education program. Dr. Estaiteyeh currently holds a Brock Chancellor’s Chair for Teaching Excellence. His research focuses on educational technologies, teacher education, STEM education, and differentiated instruction.

Email: mestaiteyeh@brocku.ca