33 ePortfolio as a strategy to enhance self-directed learning skills for personal and professional development: A policy perspective

Aloysius Claudian Seherrie

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this chapter is to explore how ePortfolios are a strategy to enhance self-directed learning skills for personal and professional development in higher education institutions (HEIs). In the South African education context, ePortfolios are increasingly being considered in teacher training programmes, not only at higher education institutions but also at primary and secondary teaching levels. Since students do not value ePortfolios and simply want to “get done” with the task, no learning can occur due to the disconnect between the vision for ePortfolio use and reality. The aim of ePortfolio use is for students to acquire the ability to both self-regulate/direct and critically reflect to shift from surface to deep learning, whereby they demonstrate their growth and development as professionals. The transformative self-directed learning theory proposes policy strategies to promote ePortfolios as a transformative strategy to enhance self-directed learning skills. Policy stipulations in the three education policies were analysed by means of thematic analysis. This chapter provides an integrative theory of Kolb’s active experiential learning and Knowles’ self-directed learning theory to put forward suggestions to use ePortfolios to promote SDL skills leading to personal and professional development in South Africa’s higher education institutions. This paper contributes to the growing interest in South African literature regarding the use of ePortfolios for teacher training by highlighting self-directed learning skills, independent learning, responsibility awareness, and learner autonomy for their own learning context. Further research should be conducted to address existing strategies that require training and policy support for the successful implementation of ePortfolios.

Keywords: ePortfolios, policy, professional development, self-directed learning, transformative strategy

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, ePortfolios have been one of the major interesting research subjects due to an increase in technology-based network communities. Professionals in various fields, such as design, writing, and photography, have also kept portfolios to document personal development and showcase their work. Ciesielkiewicz (2019) is of the view that when digital capabilities became more commonplace, the ePortfolio eclipsed its counterpart while increasing the capabilities, functions, and portability of these collections. Prior to ePortfolios and decades before the digital age, assessors and facilitators used paper-based portfolio systems, which were voluminous and tedious (Mapundu & Musara, 2019). ePortfolios are specifically used by students to display their efforts, progress, and achievements in various modules at higher education institutions (HEIs).

Scholars refer to ePortfolios as a record of documentation articulating students’ progress, skills, competencies, experiences, analysis of feedback, and achievements over time (Součková, 2024; Lu, 2021). A study by Zhang and Tur (2023) reported that ePortfolios allow students to gather evidence of learning, collaborate with peers on designing, reflect and revise, and document ePortfolios, while teachers have supervision over the process, provide continuous support and guidance, and boost students’ collaboration. An important aspect is the strengthening of technological skills, which has to be user-friendly for students to navigate self-directed learning, and, as stated by Butt (2023), the role of Industry 4.0 is enabling technologies to support digital transformation. Importantly, digital transformation includes technology integration, which involves implementing new technologies such as cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and ePortfolios to improve efficiency and innovation (Gulmira, 2024). Therefore, the ePortfolio is an important tool that is currently being used to support and document the personal, professional, and intellectual development of student teachers into self-directed learning. With the emergence of suitable advancements in technology, ePortfolios have become an important part of students’ academic life to exhibit the nature of their work and the quality of learning. They provide a personal space where students can collect their digital artefacts and creations that offer evidence of their experience, achievements, and actual learning (Jimoyiannis & Tsiotakis, 2016). In addition, students are able to enhance their educational experiences through self-directed learning (SDL) reflection, which promotes metacognition, self-observation, self-evaluation, and motivation.

This study provides an exciting opportunity to advance our knowledge of ePortfolios to enhance self-directed learning skills for personal and professional development. Many studies have investigated students’ performance and learning presence as SDL in ePortfolios (Jimoyiannis & Tsiotakis, 2016); ePortfolios as an alternative assessment strategy in an open distance learning environment (Mudau & Van Wyk, 2022); ePortfolios as a tool to enhance entrepreneurial skills (Mapundu & Musara, 2019); and exploring the effectiveness of ePortfolios (Chisango, 2024), to mention a few. This study sought to explore how ePortfolios can enhance self-directed learning skills for personal and professional development by means of a policy directive.

The notion of self-directed learning (SDL) is rooted in the theory of andragogy for adult learning (Knowles, 1975). The scholar defines self-directed learning as “a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes” (Knowles, 1975, p. 15). By linking online learning to the principles of self-directed learning, Garrison (1997) viewed self-directed learning as both a personal attribute and a learning process. SDL as a model includes three mutually interacting dimensions: self-management, self-monitoring, and motivation, which by implication means the dynamic interaction between SDL and the context within learning occurs. Portfolio management systems allow students to record the learning outcomes achieved, to determine the “positions” of the student on their own map of development and personal progress, to understand and evaluate the achievement of individual and general goals, and to learn ways of working. Educators’ willingness to use ePortfolios for self-evaluation of their own professional experience and continuous professional development remains beyond the researchers’ attention.

Emanating from this context, the following main research question was formulated for the purpose of this study: How are ePortfolios being used to enhance student teachers’ self-directed learning skills for personal and professional development through a policy directive?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Conceptualising and Contextualising Electronic Portfolios (ePortfolios)

ePortfolios are described in the literature as digital teaching portfolios (DTPs), or electronic portfolios (ePortfolios), or online teaching portfolios (OTP), but the term “ePortfolios” is used in this paper. What is evident from the literature is that ePortfolios are increasingly using innovative ways, particularly within higher education, where they have the potential to transform teaching, learning, and assessment (Elliott & Adachi, 2020; Saeed et al., 2020). With assessments to be more authentic and engaging, student learning occurs in a more hypertextual, digitalised, and multimedia world. A key element of the definition of ePortfolios is the distinction between portfolios as process and as product (Walland & Shaw, 2022).

Definitions such as these highlight the potential of portfolios to surpass their role as mere ‘collections of artefacts’, attempting instead to capture invaluable aspects of the learning process. On a generic level, electronic portfolios are part of a personal online space with a repository function and an organising function supporting collaboration and feedback (DfES, 2005). Scholars are also looking at ePortfolios for various reasons, such as assessments and course evaluations. In particular, Bates (2010) alluded to the fact that “ePortfolios enable faculty to see firsthand not only what student teachers are learning, but how they are learning” and that they play a role in assessing the effectiveness of the courses, curricula, and even institutions (pp. 15-16).

Again, ePortfolios are widely used to achieve multiple purposes in the context of teacher education, which include assessment (Chye et al., 2021; Michos et al., 2022), increased student engagement in extending and integrating knowledge, motivation, self-reflection, self-learning, and self-evaluation (Beckers et al., 2016; De Jager, 2019), and, consequently, improved learning outcomes (Marinho et al., 2021). Since this study is also looking at ePortfolios as a tool for enhancing learning, the focus is on students while studying, for graduates who prepare to move into the workforce, and for institutions for programme assessment or accreditation purposes, and ePortfolios provide a structured approach that integrates synchronous and asynchronous communication functions.

In a case study of eight South African higher education institutions, it was indicated that ePortfolios are used as an empowerment tool in teacher education programmes and as a reflection tool to enhance the professional learning of academics as teachers (van Schalkwyk et al., 2015). It can be deduced that ePortfolios play an important role in managing the performance and progress of students and the entire education system, and can be regarded as a valuable instrument in managing the academic progress of students.

Self-Directed Learning (SDL) as a Conceptual Framework

Literature has documented various principles and theories in relation to the development and use of ePortfolios as a tool for enhancing curriculum, instruction, and assessment. In this paper, two important theories will be discussed thoroughly. They are the self-directed learning theory and David Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning theory.

Self-directed learning theory

The notion of self-directed learning is rooted in the theory of andragogy for adult learning (Knowles, 1975; Means et al., 2010). According to Knowles (1975, p. 18), self-directed learning is “a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, to diagnose their learning needs, formulate learning goals, identify resources for learning, select and implement learning strategies, and evaluate learning outcomes.” By linking online learning to the principles of self-directed learning, Garrison viewed self-directed learning as both a personal attribute and a learning process. In addition, his approach put emphasis on learners’ use of resources, their motivation to learn, the learning strategies they follow, and, particularly, on collaboration with other people within a given educational context to reach their learning objectives (Garrison, 1997). Morris (2020), on the other hand, asserted that self-directed learning is a critical workplace competence that needs to be fostered in formal educational settings. ePortfolios are supported by constructivist and self-directed learning principles in that learning activities are designed to support students in constructing knowledge and understanding, both individually and collaboratively. Song (2021) is of the view that the benefits of the use of ePortfolios can facilitate the acquisition of students’ SDL skills. This view is supported by Britland (2019), who found that students who were involved in an ePortfolio peer mentoring group that focused on an extracurricular programme developed the capacity for greater self-directed learning, were willing to take charge of their own learning, and provided peer support with the assistance of the ePortfolios tool.

Furthermore, the conceptual model for understanding self-directed learning in online environments is used for contextualising the study (Song & Hill, 2007). Scholars generally argue that online learning creates many possibilities for student teachers (Zimmerman, 2000; Paris & Paris, 2001). In fact, scholars posit the SDL approach as an important endeavour in advancing distance education environments because of the unique characteristics of online environments as a physically and socially separated phenomenon (Long, 1998). “SDL” is an overarching concept related to an approach that is oriented to learning and performance achievement. Several theories focus on numerous learning processes related to outcomes-driven, self-controlled learning behaviour (Zimmerman, 2000; Paris & Paris, 2001).

Experiential learning theory

Experiential learning can be portrayed as a pedagogical practice engaging students’ active participation in their own learning journey (Farrelly & Kaplin, 2019; Mechouat, 2024). Kolb’s experiential learning theory is represented by a four-stage cycle of learning and has a more holistic approach. These four individual learning styles include concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. These four stages are an integrated learning process, and each stage is mutually supportive of and feeds into the next (Yeo & Rowley, 2020). This four-stage cycle of learning also explains how personal experience is translated through reflection into concepts, which are used as guides for new experiences. The first and second stages, concrete experience and abstract conceptualization, are two methods of comprehending experience, while the third and fourth stages, reflective observation and active experimentation, are two means of transforming experience (Kolb, 1984). Both grasping and transforming experience result in knowledge. Kolb (1984) defined this type of learning as “a process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (p. 38). The experiential learning theory advocated by Kolb asserts that experiences, cognition, emotions, and environmental factors all impact the learning process. Scholars who contributed to experiential learning are Dewey (1983), who alluded to experiential learning meaning a cycle of “trying” and “undergoing”; Freire (2000), who stressed the role of education in promoting the critical consciousness of learners; and Mezirow (2000), who believes in transformational learning and perceives it as a means to personal development. These experiential learning experiences continue to evolve, enabling us to respond and adapt to the changes that require more commitment and incorporation of innovative experiential approaches to ensure relevance and to respond to the needs of diverse groups (Mechouat, 2024).

Education Policy as Directives to Teacher Development

Education policy texts require a discussion about arguments, inscriptions, and achievements, as well as discourse for policy text as enactment, along with what is intended in such a discourse. Ball (1993) highlighted that policy text is complemented by a deliberation of policy as a discourse, mainly to elucidate what policy text comprises with regard to what can be said and thought, but also who can speak and with what authority. It is promising to find a different way of looking, a different tone, and a different way of thinking about teacher development in education (Ball, 1993; Smith & De Klerk, 2022) that allows for new perspectives and perceptions. Critically looking at the regulations of the South African education policy documents, the researcher argues that they should be understood as words of information, thoughts, and meanings about the discourse of teacher development. Policy directives contained in the National Policy Framework for South African Teacher Education and Development in South Africa (NPFTED) (RSA, 2007) aimed to achieve a community of competent teachers dedicated to providing education of high quality, with high levels of performance and ethical and professional standards and conduct. The professional education and development of teachers work best when teachers are involved in it, reflecting on their own practice, and when activities are well coordinated (RSA, 2007). The South African Council for Educators (SACE) (RSA, 2013) has the duty to implement and manage the continuous professional teacher development system in South Africa. SACE keeps a record of all professional teachers, guarantees that all teachers conduct themselves professionally, and manages a structure for the advancement of continuing professional development of South African teachers (RSA, 2013). Since teachers must take charge of their self-development and grow professionally, this emphasises greater professional autonomy and requires teachers to have new knowledge and applied competencies, which serve as a fertile ground for self-directed learning.

ePortfolios as an Enabler to Teachers’ Personal and Professional Development

The professional development of teachers has piqued the interest of governments and researchers alike as they acknowledge the positive effect CPD has on learner performance and teacher and teaching quality. The advantages of good quality teachers and teaching cannot be overstated. Despite the various factors that may influence the objective of quality education, including school, higher education context, teaching and learning resources, working conditions, and teacher governance, it remains that teacher training is the most impactful (Beka & Kulinxha, 2021; Sayed et al., 2020; Singh & Mukeredzi, 2024). Multicultural organisations, such as UNESCO, have engaged intensively with African states as a mechanism for improving the provision of public education on the continent. UNESCO, in consultation with SADC countries, has stated the importance of improving the quality of teachers, which has led to two key priorities: teacher standards and competencies and CPD (UNESCO, 2020). South Africa’s professional development is in a good state since its policy regulation is impressive. Policy frameworks regulate the professional development of teachers and how the profession is governed by the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ), and professional development for qualified teachers is governed by the Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development (ISPFTED). As this is a continuous process, the beginning of developing a teacher does not necessarily start at the onset of initial teacher education (ITE), but teacher development starts when the teacher-to-be is still a learner at school. What teachers do or do not is in response to their early learning experiences (Allender & Allender, 2006).

It is important to note that training for teacher development is referred to as Continuous Professional Development (CPD), often interchanged in the literature as Continuous Professional Teacher Development (CPTD) or Teacher Professional Development (TPD). An interesting point is that the principal tool that countries across the income spectrum use to improve the knowledge and skills of their practicing teachers is professional development (PD), which may take several forms, like on-the-job training activities ranging from formal, lecture-style training to mentoring and coaching (Popova et al., 2022). Another definition of CPD is regarded as activities that increase the knowledge and skill base of teachers (Sayed & Bulgrin, 2020).

Self-reflection is one of the most important competencies that a teacher should possess. Reflection enables the identification of things that are not only a strong part of professional work but also need to be advanced and allows a higher level of professionalism. In terms of taking individual responsibility for thought and action processes, self-reflection is a required condition for assessment and regulation. We tend to reflect on things we accomplished, but sometimes our attention is drawn to the successes or the most challenging, and we may forget the things that may be equally important for enhancing the quality of one’s work and for continuing professional development. Through the use of portfolios, pre-service teachers can succeed in developing a professional working plan, reflect on their work, develop additional skills in the use of technology for professional development, and have a clear review of their work (Beka & Gllareva, 2016). Portfolios for self-reflection in pre-service teacher training provide vital input for trainers since they represent both the strengths and weaknesses of students (Cimermanová, 2019). Portfolios play a significant role in not only the process of preparing teachers for employment but also in their licensing as teachers and coaches and their state-level performance appraisals. Being reflective is a key aspect of any educational experience. It involves the continuous educational growth of both professional educators and students (Webster & Whelen, 2019).

ePortfolios help student teachers grow by encouraging continuous self-evaluation through reflection on their own strengths and weaknesses, identification of knowledge and competency gaps, celebration of accomplishments, assessment of future directions, and conversation with others. Student teachers’ experiences during teaching practice have a significant impact on their subsequent integration of technology upon entering the field. With the assistance of mentor teachers, student teachers become empowered to develop ePortfolios. Student teachers are assisted in technology integration. During this process, student teachers are provided with knowledge on how to utilize content and technological and pedagogical expertise effectively for the benefit of pupils’ learning (Hodges, 2018). The creation and management of an ePortfolio provides student teachers with opportunities to build digital fluency, using technologies to create, select, organise, edit, and evaluate their work. The advantage of the interactive nature of peers, students, lectures, or instructors with content during the online engagement, ePortfolios resulted in high-quality products and more effective outcomes (Mudau & Modise, 2022). Since e-learning approaches were suggested by Modise (2021), there has been a new hype of interest in ePortfolios that are more student-centred and have been found to promote self-directed learning and lifelong learning (Van Wyk, 2018). Scholars agree that teachers can share and critique information in the ePortfolio collectively by giving constructive feedback to student teachers on the quality and authenticity of evidence that is produced (Lai et al., 2016). Another educational value of an ePortfolio is that student teachers can share information, collaborate to complete group tasks, reflect critically on their writing, and critique one another’s work in a collegial manner (Oakley et al., 2014). A recent literature review by Boulton (2014) identifies several educational benefits, such as self-directed learning, professional development, assessment, job applications, and promotions, as key indicators for using ePortfolios.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

Research Design and Paradigm

This paper employs a qualitative methodological research design that embraces the collection and analysis of non-numerical data such as texts in documents and policies (Bhandari, 2020). In this paper, texts in the Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (2014), the Open Learning Policy Framework for Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2017), and Education White Paper 3: A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education (DoE, 1997) were analysed to determine policy strategies on how ePortfolios can be used to enhance self-directed learning as an innovative, transformative, and alternative assessment strategy. In the case of conceptual papers, opinions are not resulting from facts in the conventional sense but comprise the integration and grouping of information relevant to previously developed ideas and philosophies (Hirschheim, 2008). This implies that conceptual papers are not without practical understandings but rather elaborate on concepts and theories that are advanced and verified through experimental inquiry (Jaakkola, 2020). In this paper, we regard a conceptual research design (CRD) as applicable because it is generally referred to as research related to concepts and ideas about a phenomenon under study to solve real-world problems (Hirschheim, 2008). In policy studies, an application of CRD may assist researchers to analyse policy content, enabling them to excavate possible policy solutions to address particular issues (Farrell & Coburn, 2016). In this study, a CRD was useful because it enabled us to explore how stipulations in education policies can provide innovative assessment strategies that can be applied by HEIs to equip pre-service teachers with capabilities. Furthermore, conceptual research can be useful to go beyond existing ideas in stimulating ways, connect information across fields of specialization, provide innovative understandings, and widen the space of individual thinking (Gilson & Goldberg, 2015). In so doing, we believe that knowledge of transformative learning can no longer be understood, explained, communicated, illustrated, grouped, and told in the same way (Foucault, 1973). We take this view to mean that a CRD assisted us in rejecting grand narratives and identifying potential policy options that could address issues of SDL, comparing those options, and then choosing the most effective, efficient, and feasible option to be implemented.

Ethical Considerations

In the present research, the researcher studied the policy documents and their various provisions that promote the creation, sharing, and distribution of ePortfolios and innovative assessment strategies, especially with reference to Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (2014); the Open Learning Policy Framework for Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2017); and Education White Paper 3: A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education (DoE, 1997).

Sampling

A purposive sampling method was used to select policies that are freely accessible and open to the provision of teaching resources that are already in the public domain. The search yielded 6 policies related to ePortfolios and Self-Directed Learning (SDL) relevant to higher institutions in South Africa. Of the 6 policies, three were chosen and three excluded on the basis that they do not explicitly speak to ePortfolios and SDL. The three policies chosen are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Policy distribution (created by Author)

|

Document Policy Level |

Policy Type and Document Link |

Year |

|

South African governmental and policy-level document |

Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications, 2014 |

2014 |

|

South African governmental and policy-level document |

The Open Learning Policy Framework for Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2017). |

2017 |

|

South African governmental and policy-level document |

Education White Paper 3: A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education (DoE, 1997) |

1997 |

Data Collection Process and Analysis

The researcher has collected data by consulting the following policies: Firstly, Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ), 2014; secondly, The Open Learning Policy Framework for Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2017); and lastly, Education White Paper 3: A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education (DoE, 1997). The researcher analyses stipulations from these three South African policy documents that address ePortfolios and SDL in higher education. The words of Coffey and Atkinsen (1994) remind us that “there is no single right way to analyse qualitative data.” This assertion clarifies the contention that researchers should consider alternative strategies to use data (Snyder, 2019). Indeed, borrowing from Lochmiller and Lester (2017), qualitative data analysis often aligns with a particular methodology, theoretical perspective, research tradition, or field. The researcher has selected specific stipulations from the policies that have the strongest connection to ePortfolios and SDL and were analysed employing thematic analysis (Lester, Cho & Lochmiller, 2020). There were no set rules for deciding on the sample number concerning the total stipulations that were analyzed (Patton, 2002). However, we were cognizant that the number of stipulations would be sufficient to make meaning about the enactment of ePortfolios and SDL.

Data Analysis

The researcher followed the following steps in analysing the data: the first step was to prepare and organise the data (selected from the policy stipulations) for thematic analysis. By doing so, the researcher became familiar with and accurately recorded any early responses to the corpus of data as well as identified any limitations and gaps in the data collected. Any gaps could be marked as areas for further research. Secondly, the researcher reviewed the data and generated memos for reflection and interpretation. During the third step, the researcher assigned codes to the data to identify important statements, experiences, and reflections. Following the fourth step, the researcher assigned additional codes to move coding to a higher level of inference. This assisted the researcher in reflecting on ideas that were linked to the focus of my study. Fifthly, the researcher developed categories to understand how the codes relate and contrast with each other, thus recognizing similarities, differences, and relationships across categories, which resulted in themes for analysis. To provide understanding, data analysis in this paper thus consisted of a process of reading through the data, applying codes to excerpts, conducting various rounds of coding, grouping codes according to themes, and then making interpretations of the policy stipulations that led to the ultimate research findings. Three themes were identified: SDL characteristics, ePortfolio as an alternative assessment, and personal and professional development.

The intention of the policy was to transform and redress past inequalities, serve a new social order, meet national needs, and respond to new realities and opportunities. The view is that policies aim to foster teacher development to ensure that teachers, and particularly in-service teachers, become self-reliant and self-knowing experts who will be able to demonstrate self-directed learning skills.

Significance for Policy Analysis

According to Brown, Coffey, Cook, Meiklejohn, and Palermo (2018), a policy is generally considered to be the interaction of resources, values, and interests directed through organisations and facilitated by the government, while policy analysis cannot be regarded as a straightforward activity due to incongruence regarding policy means and how it should be understood and analysed (Peters, 2015). De Klerk (2014) opines that any discourse on policy needs a form of analysis, and the author agrees with Olssen, Codd, and O’Neill (2004), who postulate that analysing policies is not about understanding them as the declarations of policy-makers but needs a deeper interpretation as such. A very appropriate policy analysis that suits this study is the interpretive perspective policy analysis. O’Connor (2005, pp. 4-5) argues that an interpretive perspective approach is based on “an understanding that the world is as it is and on appreciating the important nature of the social world at the level of individual experience.” This study will implement an interpretive perspective on policy analysis and, as a result, further the debate on ePortfolios and SDL in higher education. This aligns with the interpretive approach to policy analysis because it clears the way for critical consciousness-raising about policy texts (Freire, 1970; O’Connor, 2005).

FINDINGS

This concept paper decodes stipulations in the Government Policy: Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (2014); the Open Learning Policy Framework for Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2017); and Education White Paper 3: A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education (DoE, 1997).

Policy on the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications, 2014

The policy on “Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications” (Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), Republic of South Africa, 2015:12) stipulates that competent learning is always a mixture of the theoretical and the practical, the pure and the applied, the extrinsic and the intrinsic, and lastly, the potential and the actual. In effect, competent learning represents the acquisition, integration, and application of different types of knowledge. Each type of knowledge, in turn, implies the mastery of specific related skills. The types of learning associated with the acquisition, integration, and application of knowledge for teaching purposes are disciplinary learning, pedagogical learning, practical learning, fundamental learning, and situational learning (DHET, 2015:12). For the purpose of this study, the researcher will focus explicitly on practical learning since it relates to innovative teaching and learning methods. Regarding practical learning, the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) is clear, where it states:

Practical learning involves learning from and in practice. Learning from practice includes the study of practice, using discursive resources to analyse different practices across a variety of contexts, drawing from case studies, video records, lesson observations, […] Learning in practice involves teaching in authentic and simulated classroom environments. Work-integrated learning (WIL) takes place in the workplace and can include aspects of learning from practice (e.g., observing and reflecting on lessons taught by others), as well as learning in practice (e.g., preparing, teaching, and reflecting). Practical learning is an important condition for the development of tacit knowledge, which is an essential component of learning to teach (DHET, 2015:12).

Phrases like “practical learning involves learning from and in practice,” “work-integrated learning (WIL) takes place in the workplace,” and “discursive resources” will be used to demonstrate how ePortfolios as a strategy can be used to enhance self-directed learning skills for personal and professional development.

Looking at Section 3.10, which refers to the different types of learning and knowledge, indicates the dependency on the purpose of the qualification and provides the basis for the design of curricula for specific learning programmes. […] for the purpose of this study, the following stipulations will be highlighted:

Professional ethics and the development of professional attitudes and values constitute key elements of all teacher education programmes. Different mixes of knowledge and related skills result in the development of different kinds of competencies. (DHET, 2015:11).

The researcher argues that phrases like “professional ethics,” “the development of professional attitudes and values,” “knowledge and related skills,” and “different kinds of competences” imply that teachers are afforded opportunities by these policies to make autonomous decisions regarding their own professional development. Frostenson (2015) noted that teacher autonomy becomes significant for teachers’ responsibility to influence their own practices and empowers them subsequently to enhance their agency.

Another important section is Section 18: Appendix C, “Basic Competences of a Beginner Teacher.” The emphasis is on the minimum set of competencies required of newly qualified teachers, and the researcher will highlight the most relevant to this study. Competencies for this study are included as follows:

Newly qualified teachers must have highly developed literacy, numeracy, and information technology (IT) skills; and lastly, they must be able to reflect critically on their own practice in theoretically informed ways and in conjunction with their professional community of colleagues to constantly improve and adapt to evolving circumstances. (DHET, 2015:62). From the extract, the researcher extracts two stipulations that talk to critical skills and reflexive teaching: firstly, the term “information technology skills,” and secondly, “reflect critically on their own practice.”

The Open Learning Policy Framework for Post-School Education and Training (DHET, 2017)

It puts the DHET at the center of OER policy creation, as well as creating an OER-supportive environment (DHET 2017). On OER funding, this policy mentions that it will support the development of “an enabling policy environment for the development, use, and distribution of OER” and would make “all materials developed by the DHET and institutions through public and donor funding will be made available as OER” (p. 28).

Make high-quality, shared teaching and learning resources available as open educational resources.” (Section 3.2.5) (DHET, 2017), p. 28

This policy emphasises that cost-efficiency is most important for quality open educational resources in an open learning environment. As stated in the policy, “a collaborative growth and sharing of well-designed, quality teaching and learning resources as OER is paramount in open learning.”

The researcher draws on phrases like “cost-efficiency,” “collaborative growth,” and “sharing of well-designed, quality teaching and learning resources” as OER. This policy supports OER, but it also creates a conviction that OER is generally still recognised as a norm and standard that warrants public funding. This indicates a more flexible use, reuse, and adaptation of materials for local contexts and learning environments, and at the same time, allows authors to have their work acknowledged. In summation, this policy supports the sustainable development and sharing of quality learning and teaching material, which can include case studies or any good practices, through the rapid digitisation and online sharing of information and resources.

Education White Paper 3: A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education (DoE, 1997)

In South Africa today, the challenge is to redress past inequalities and to transform the higher education system to serve a new social order, to meet pressing national needs, and to respond to new realities and opportunities. The Education White Paper 3 – A Programme for Higher Education Transformation is the culmination of a wide-ranging, extensive consultation process that gives expression to the democratic will of an emerging nation and has resulted in the building of an all-embracing consensus of all the key stakeholders in higher education. This White Paper is directed by fundamental principles that guide the process of transformation in the spirit of an open democratic society based on human dignity, equality, and freedom. It is followed by key targets and outcomes that should be enhanced and implemented in the transformation phase. (DoE, 1997: 10) Goals are:

To secure and advance high-level research capacity, which can ensure both the continuation of self-initiated, open-ended intellectual inquiry and the sustained application of research activities to technological improvement and social development. Goal 1.27: (7)

The researcher will highlight stipulations like “self-initiated” and “open-ended intellectual inquiry.” These phrases underscore the importance of self-directed learning initiatives and how an ePortfolio can be used as a tool to promote SDL.

To produce graduates with the skills and competencies that build the foundations for lifelong learning, including critical, analytical, problem-solving, and communication skills, as well as the ability to deal with change and diversity, in particular, the tolerance of different views and ideas. Goal 1.27: (9)

Furthermore, stipulations from the above extract, which are “skills and competencies […] for lifelong learning,” “critical,” “analytical,” “problem-solving,” “communication skills,” and “tolerance,” refer to the skills that a self-directed learner must acquire to demonstrate self-directedness.

DISCUSSION

Transformative Policy Implications for Higher Education Institutions

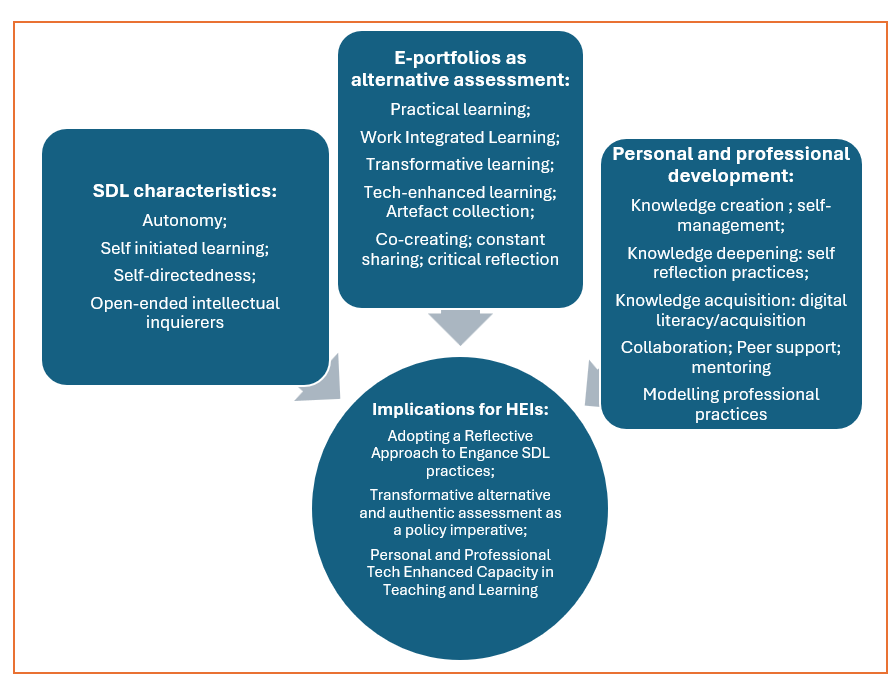

Transformative advancements regarding ePortfolios are indicated in various policy documents and are exacerbated by narrow thoughts on policy directives, shifting of policy associations, and uncertainties as to how ePortfolios can enhance self-directed learning for improved personal and professional development. Consequently, it has to be emphasised that this is not pertinently demonstrated by policy; how could it enact SDL? Arguably, policy directives may contribute to the advancement of the use of ePortfolios and, specifically, students’ confidence to gain an understanding of how to apply such practices during their studies. Fostering innovative and alternative assessment practices, from a policy perspective, are illustrated in the following figure.

Figure 1

Transformative Policy Implications for Higher Education Institutions

This study sought to propose policy strategies on how ePortfolios can be used to enhance self-directed learning as an innovative, transformative, and alternative assessment strategy. The findings show that South Africa recognises ePortfolios as an innovative alternative assessment, and policy for this activity exists across regulatory documents in pieces and fragments. The current problem was, therefore, the issue of policy quality rather than policy existence. This study will first look at ePortfolios as an alternative assessment, secondly, at SDL characteristics, thirdly, at personal and professional development, and lastly, at the implications for higher education institutions.

Looking at the definition of Jenson and Treuer (2014), they alluded to the fact that an ePortfolio is a digital tool for compiling and managing learning over a period to enhance authentic and continuous learning. Scholars like Mudau and Modise (2022) supported this finding and state that although ePortfolios are student-centered, teachers still have an important role to play in designing the learning environment and approaches employed therein. The findings revealed that MRTEQ emphasises that the focus should be placed on “Practical learning is an important condition for the development of tacit knowledge, which is an essential component of learning to teach” (DHET, 2015:12). Furthermore, MRTEQ also points to “the ability of teachers to draw reflexively from integrated and applied knowledge” (South Africa, 2015, p. 11) and “explicit placing of knowledge …in the foreground; it gives renewed emphasis to what is to be learned and how it is to be learned” (South Africa, 2015, p. 11). Since integrated knowledge requires people to build on their know-how and experience (Bates, 2010), it was also important that applied knowledge can be associated with the ability to apply experience and skills to understand and perform in an advanced manner (Davis, 2020). By implication, HEIs should deliberately emphasise practical learning for students to be architects of authentic learning environments (DHET, 2015). This notion is further supported by Marinho et al. (2021), who agree that the know-how principle can consequently lead to improving learning outcomes. An interesting point of Kolb (1984) is that instant experience is a form of transformative learning, which is emphasised as a policy requirement.

Work-integrated learning (WIL) facilitates practical learning and is a vital component of professional development in higher education (Zegwaard et al., 2023). WIL takes place “in the workplace” (DHET, 2014) and is best understood as a pedagogical approach among the student, the educational institution, and industry. When students participate in WIL, “students learn through active engagement in purposeful lesson planning, which enables the integration of theory with meaningful teaching practice that is relevant to the students’ subject methodology and/or professional development.” (Zegwaard et al., 2023, p. 38). This implies that students studying teacher education are exposed to school and classroom settings, which are crucial for the 21st-century student teachers’ toolkit. When students observe their mentors, they learn from experienced teachers and obtain a valuable understanding of the complexities of instruction and management, which demonstrates their application of theoretical knowledge through engaging in real-life teaching activities in the field practice placements during teaching practice (Du Plessis et al., 2010; Nielsen, 2024). To further support the idea of ePortfolios as innovative assessment strategies within higher education, they have the potential to transform teaching, learning, and assessment (Elliott & Adachi, 2020), which fosters a more tech-driven, digitalised multimedia world (Saeed et al., 2020). Globally, Education 4.0 compels educators to rethink disruptive pedagogies and innovative alternative assessment practices to prepare students for the challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), which can empower them with high-level cognitive skills and equip them with analytical, critical, and reflective ways to ask questions, make informed decisions, and learn independently (Tikhonova & Raitskaya, 2023).

Institutional autonomy refers to a high degree of self-regulation and administrative independence. From the literature of the self-directed learning perspective, autonomy thus requires that the student teachers apply the conditions of self-rule, self-determination, and self-ownership, where teachers make decisions for themselves. Apart from an institutional viewpoint, ePortfolios allow student teachers’ autonomy and the capacity to self-govern, which is the ability to act independently, responsibly, and with the greatest conviction. The South African higher education policy states that,

The principle of institutional autonomy refers to a high degree of self-regulation and administrative independence with respect to student admissions, curriculum, methods of teaching and assessment, research, establishment of academic regulations, and the internal management of resources generated from private and public sources. Such autonomy is a condition of effective self-government. (RSA, 1997, p. 8).

Phrases like “autonomy,” “self-regulation,” “independence,” “respect,” “methods of teaching and assessment,” and “condition of effective self-government” demonstrate that ePortfolios provide student teachers the capacity to self-govern, which is the ability to act independently, responsibly, and with the greatest conviction. Borrowing from the work of Motloba (2018), SDL becomes an essential act of autonomy, which involves liberty or freedom and the competence to interpret information. Motloba asserts that liberty and freedom can be influenced by external factors, which can enable or curb the process of free decision-making. Independent decision-making forms an inherent attribute of self-directed learners, which enables them to be open-minded in decision-making. The capability of intention, where someone has the ability and competence to interpret information, and where a decision is reached, is also characteristic of a self-directed learner, where self-regulation and self-government form part of the self-directed learner’s self-determination skills.

Self-initiated open-ended intellectual inquiry aims to intensify learning through an investigation of previously held mistakes, beliefs, and decisions, as well as an openness to innovative thoughts (Lord, 2015). This self-explanatory, multifaceted construct requires pre-survival teachers to be initiators, socially just, open-minded, and knowledgeable inquirers. Such students have to illustrate sound conveyors of knowledge, demonstrate deeper understanding of the self as well as others, and have the inner ability of self-help. Inquiry is an active learning process that learners use to learn, and it is a skill that most scholars have applied over the years (Lin et al., 2018). In this regard, South African higher education policies indicated that HEIs should:

Secure and advance high-level research capacity, which can ensure both the continuation of self-initiated, open-ended intellectual inquiry … only a multi-faceted approach can provide a sound foundation of knowledge, concepts, academic, social, and personal skills, and create the culture of respect, support, and challenge on which self-confidence, real learning, and enquiry can thrive and the sustained application of research activities to technological improvement. (RSA, 1997, p. 9)

Words like “self-initiated,” “self-confidence,” “open-ended,” and “intellectual inquiry” are essential elements of self-directed learning and transformative learning because they highlight some of the fundamental attributes of a self-directed learner when a transformative approach is promoted. However, it is paramount for HEIs to promote pre-service teachers’ capacity regarding transformative self-directed learning approaches in which they participate in relation to cognitive, emotional, and social orientation (Oxford, 2017). This approach aligns with Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning approach, whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience and the application of self-initiated inquiry skills within a self-directed learning environment.

The teacher’s ePortfolio is a personal digital document where, with the help of creativity and innovative technologies, it is possible to demonstrate professional competencies and learning style (Vorotnykova & Zakhar, 2021). ePortfolios can be used as a tool for self-assessment, reflection, and learning to reflect. The ePortfolio is now the platform that students can use to compile, organise, and formulate a digital presentation across various types of media and can be updated and adapted over time for different purposes and audiences (Ciesielkiewicz, 2023). Portfolios support a reflective approach to enhancing academic practice and enable us to make ‘our tacit, automatic knowledge and methods more explicit, allowing us to build on good practice and develop a professional “repertoire” for future problem solving’ (Hughes & Moore, 2007, p. 12). While professional development portfolios can take multiple forms and approaches, a common thread running throughout is a focus on reflective practice and engaging in continuous cycles of reflection in order to continuously enhance and improve practice. It is imperative that all teachers register with professional bodies to earn professional development points by undergoing approved professional development activities that meet their development needs (Republic of South Africa, 2007; Gomba, 2019). The worth of teachers’ professional work underpins the worth of education, and the improvement of these teaching practices is an ongoing process that continues throughout the career of a dedicated professional teacher. Policy also advocates for holistic digital literacy that considers the needed digital competencies of the twenty-first-century educators. It is important to emphasise the role of teachers and students through collaborative learning by introducing metacognitive and self-development teachers’ competencies (Nascimbeni, 2018). For students to successfully adopt collaborative learning practices, they do not need to acquire new competencies but rather require adapting their teaching strategies to collaborative learning settings.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS (HEI)

Adopting a Reflective Approach to engage Self-directed Learning Practices

Reflection is the most critical component in an ePortfolio initiative. It is a form of students’ critical thinking on individual and peer work, knowledge material, artefacts, and creations towards fulfilling a specific purpose or achieving the anticipated learning outcomes (Jimoyiannis & Tsiotakis, 2016). These scholars also alluded to the fact that ePortfolios operate as participatory spaces supporting constructive and collaborative learning processes, whereby students set their learning goals, and they attempt to monitor, control, regulate, and co-regulate their motivation, cognition, engagement, and learning processes. The researcher argues that using SDL as a lens, ePortfolios can bind learning to problem-solving, individual and group learning, collaboration, and professional development. One can conclude that the pedagogical affordances of ePortfolios can strengthen and improve reflection in such a way that helps students to achieve meaning and knowledge from their formal learning experiences, self-directed initiatives, and collaborative experiences. Furthermore, meaningful reflection is best facilitated by peer collaboration, artefact co-creation, mentoring, and peer feedback within a learning community evolving in the ePortfolios.

ePortfolios were being used for alternative assessment, enhancing authentic, self-directed learning (lifelong learning and life-wide learning), and promoting student self-reflection. Horris and Liguori (2016) assert that there is a great need to encourage students to become reflective and introspective whilst documenting their self-critical reflection on the application of the ePortfolio tool. Since ePortfolios improve students’ self-confidence, academic performance, and their ability to integrate theory and practice (Elshami et al., 2018), HEIs assist in shaping students for the world of work (Carter, 2021), and therefore, students should be afforded opportunities to develop their future professional identities to show their desired skills and competencies (Chisano, 2024). Throughout the process of collecting, compiling, and reflecting on authentic evidence, student teachers are taking ownership of their learning process because they want to produce the best ePortfolios.

Transformative alternative and authentic assessment as a policy imperative

Alternative assessment in the 21st century illustrates the importance of assessment practices that promote higher-order thinking, allowing students to be innovative and create their own learning as active participants (Mudau & Van Wyk, 2022). Therefore, a new approach to teaching and learning requires lecturers to change their teaching strategies, methods, and assessment practices. Kumar (2025) refers to the evolution of education from Education 1.0 (E1.0) to Education 4.0 (E4.0), whereby E4.0 indicates the integration of advanced technologies in the education system. Education 4.0 requires educators to rethink disruptive pedagogies and innovative alternative assessment practices to prepare students for the challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), which includes artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and big data analytics (Moraes, 2023). The challenge posed by 4IR is to create learning opportunities for students to be empowered with high-level cognitive skills and to equip them with analytical, critical, and reflective skills to make informed decisions, ask questions, be problem solvers, and learn independently (Gerstein, 2014; Hussin, 2018). The ePortfolio is a multi-model, evidence-based strategy currently introduced to most teacher education programmes at HEIs locally and globally (Boulton, 2014).

In these HEIs, ePortfolios are used as an alternative assessment tool for student teacher empowerment and promotion. Teacher education programmes at HEIs require prospective students to compile either a paper-based portfolio or a portfolio of evidence as part of a teaching qualification. The purpose of a teaching portfolio is, according to Grandberg (2010), to meet the need for national standards or address issues of accreditation, which may include those of promotions, teacher awards, and certification programmes in higher education (Fitzpatrick & Spiller, 2010). Since ePortfolios are used to encourage students to engage in professional learning where they provide evidence of their teaching practices, they enhance their teaching because they take responsibility, evaluate themselves, and become agents of transformation (CHE, 2017; DHET, 2018).

Furthermore, there is no single policy that compels HEIs to use ePortfolios as a compulsory assessment. Many HEIs have implemented policies that encourage ePortfolio pedagogy that can be used as an alternative, innovative, and authentic assessment practice that showcases skills and achievements and reflects and uses appropriate communication modalities (Boulton, 2014). One particular open distance learning (ODL) university has introduced an alternative assessment approach as part of the assessment policy. During its strategic planning for 2016-2030, they have decided to reconfigure and review their assessment strategies and practices to determine students’ learning achievements. The HEI has introduced various alternative assessment strategies that can be used to determine students’ performance, which include multiple-choice questions (MCQs), take-home examinations, open-book examinations, research projects, and ePortfolios. The lecturers could choose to use an ePortfolio as an alternative assessment tool for their respective courses or modules. On completion of the required evidence collected, the ePortfolio is uploaded as a final production of a learning management system (LMS), students’ learning management system portal, to be assessed (Mudau & Van Wyk, 2022).

Personal and professional tech-enhanced capacity in teaching and learning

Personal and professional development are infused in the concept of professional identity. Professional identity can be defined as “The self that has been developed with the commitment to perform competently and legitimately in the context of the profession, and its development can continue over the course of the individual’s career” (Tan et al., 2017, p. 1505). This section emphasises the importance of personal and professional digital capacity and the application of digital skills and knowledge to professional practice. It is imperative that teachers and students develop personal confidence in digital skills to develop professional competence and the identification of opportunities for technology to support and enhance student learning (Pelger & Larsson, 2018). It is widely accepted that professional development to enhance academic practice amongst those who teach in HEI includes a wide range of formal accredited programmes, non-accredited or informal professional activities such as workshops, training, and experimental approaches related to teaching and learning.

Professional learning takes place through experiential or work-based practices, including communities of practice, conversations with colleagues, and practice-based innovations. Based on the latter, it is evident that “the principal tool that countries across the income spectrum use to improve the knowledge and skills of their practicing teachers is professional development (PD), which refers to on-the-job training activities ranging from formal, lecture-style training to mentoring and coaching” (Popova et al., 2022). Furthermore, MRTEQ emphasises that newly qualified teachers must have highly developed literacy, numeracy, and, most importantly, information technology (IT) skills. This must be pursued in collaboration with their professional community of colleagues to constantly improve and adapt to evolving circumstances (DHET, 2015). Therefore, teachers have to be continuously trained and professionally developed to enhance their personal attributes, roles, competencies, and standards.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this paper was to provide a theoretical lens from a South African education policy perspective into how ePortfolios provide an opportunity for student teachers to advance their knowledge and to enhance self-directed learning skills for personal and professional development in HEIs. The researcher applied Kolb’s and Knowles’ learning theories as an approach that uses integration to aid educational processes so that students transform learning spaces through policy discourse. Analysis of policy discourse in three policy documents revealed that students can use ePortfolios as an alternative and innovative assessment resource to develop SDL skills and enhance their personal and professional development.

This paper supports earlier findings in the literature that focus on alternative and innovative assessment practices of HEIs in fostering the skills, knowledge, and values of student teachers for shaping their professional identity. It must be emphasised that not all HEI policies are rigid in how to apply their assessment policies but allow the space and freedom for HEI teachers to apply their minds and their own discretion.

Another contribution of this paper is the enrichment of understanding that engaging assessment practices demand that student teachers wield their own power as knowledgeable and critical people who can be capacitated to guide learners in the classroom settings. Importantly, the study has implications for the teaching of professional development opportunities as per the CPTD.

Significantly, creating transformative learning environments for knowledge creation, knowledge deepening, and knowledge acquisition requires continuous monitoring, collaboration, and support for student teachers as imperatives and thus has CPTD policy implications. Further research should be conducted to address existing strategies that require training and policy support for the successful implementation of ePortfolios in HEIs.

REFERENCES

Allender, J., & Allender, D. (2006). “How did our early education determine who we are as teachers?,” in Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices, eds. L. M. Fitzgerald, M. L. Heston, and D. L. Tidwell (Cedar Falls, IA: University of Northern Iowa), 14–17

Bates, T. (2010). New challenges for universities: Why they must change? In D. Ehlers & D. Schneckernberg (Eds.). Changing cultures in higher education. Moving ahead to future learning (pp. 15–25). Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03582-1_2

Ball, S. J. (1993). “What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories, and Toolboxes.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 13 (2): 10–17. doi:10.1080/0159630930130203

Beckers, J., Dolmans, D., & Van Merri€enboer, J. (2016). ePortfolios enhancing students’ self-directed learning: A systematic review of influencing factors. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2528

Beka, A., & Gllareva, D. (2016). The importance of using electronic portfolios in teachers’ work. Applied Technologies and Innovations, 12(1), 32–42. http://doi.org/10.15208/ati.2016.03

Beka, A., & Kulinxha, G. (2021). Portfolio as a tool for self-reflection and professional development for pre-service teachers. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 20(2), 22-35. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.20.2.2

Bell, A. (2009). Exploring Web 2.0: Second generation interactive tools – blogs, podcasts, wikis, networking, virtual worlds, and more. Georgetown, TX: Katy Crossing Press.

Boulton, H. (2014). ePortfolios beyond pre-service teacher education: a new dawn? European Journal of Teacher Education 37(3):374–389. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2013.870994

Chang, S. L., & Kabilan, M. K. (2024). Using social media as ePortfolios to support learning in higher education: a literature analysis. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 36(1), 1–28.

Chisango, G. (2024). Exploring the effectiveness of ePortfolios in a first-year undergraduate project management course. SOTL in the South, 8(3), 25–43.

Chye, S., Zhou, M., Koh, C., & Liu, W. C. (2021). Levels of reflection in student teacher digital portfolios: A matter of sociocultural context? Reflective Practice, 22(5), 577–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2021.1937976

Ciesielkiewicz, M. (2019). The use of ePortfolios in higher education: From the students’ perspective. Issues in Educational Research, 29(3), 649–667. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.641203511753765

Cimermanová, I. (2019). Teaching portfolio as a source of pre-service teacher training programme needs analysis. Pedagogika, 131(3), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.15823/p.2018.42

Cook, J. (2004). Electronic portfolios for learning and assessment. Interact, 29, 3–4.

Council on Higher Education. (2017). Higher Education Monitor 14. Pretoria: CHE.

Cotterill, S. (2007). What is an ePortfolio? Retrieved from http://www.epics.ac.uk/?pid=174

De Jager, T. (2019). Impact of ePortfolios on science student-teachers’ reflective metacognitive learning and the development of higher-order thinking skills. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 16(3), 3

De Klerk, E. D. (2014). Teacher Autonomy and Professionalism: A Policy Archaeology Perspective. PhD dissertation. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University.

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2015). Revised policy on the minimum requirements for teacher education qualifications. 596(38487). Pretoria: Government Printers.

Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). (2018). A national framework for enhancing academics as university teachers. Pretoria: Government Printers.

De Swardt, M., Jenkins, L. S., Von Pressentin, K. B., & Mash, R. (2019). Implementing and evaluating an ePortfolio for postgraduate family medicine training in the Western Cape, South Africa. BMC Medical Education, 19, 1–13.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY.

Du Plessis, E. C., Marais, P., Van Schalkwyk, A., & Weeks, F. (2010). “Adapt or die: The views of UNISA student teachers on teaching practice at schools.” Africa Education Review 7(2), 323‒341. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2010.515401

Elliott, J., & Adachi, C. (2020). Building their portfolio: Using ePortfolios in teacher PD to build capacity. ePortfolio Forum.

Elena, T., & Lilia, R. (2023). Education 4.0: The concept, skills, and research. Journal of Language and Education, 9(1 33), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2023.17001

Elshami, W.E., Abuzaid, M.M., Guraya, S.S. & David, L.R. (2018). Acceptability and potential impacts of innovative e-portfolios implemented in e-learning systems for clinical training. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 3(6):521‐527.

Farrelly, D., & Kaplin, D. (2019). “Using student feedback to inform change within a community college teacher education program’s ePortfolio initiative,” The Community College Enterprise, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 9–38. 2019.

FitzPatrick, M.A. & Spiller, D. (2010). The teaching portfolio: institutional imperative or teacher’s personal journey? Higher Education Research & Development 29(2), pp. 167–178.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury.

Garrison, D. R. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive model. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(1), 18–33.

Granberg, C. (2010). ePortfolios in teacher education 2002–2009: the social construction of discourse, design, and dissemination. European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(3), pp. 309–322.

Hodges, C. B. (Ed.). (2018). Self-efficacy in instructional technology contexts. Springer, Switzerland.

Hughes, J., & Moore, I. (2007). ‘Reflective portfolios for professional development’ in O’Farrell, C., ed., Teacher Portfolio Practice in Ireland: a handbook, Dublin: AISHE, 11–23.

Jimoyiannis, A., & Tsiotakis, P. (2016). Self-directed learning in ePortfolios: Analysing students’ performance and learning presence. EAI Endorsed Transactions on E-Learning, 3(9). https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.11-4-2016.151154

Kumar, S. (2025). Education 4.0: Transforming Learning for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Higher Education for the Future, 23476311251326140. https://doi.org/10.1177/23476311251326140

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning. New York: Association Press.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (vol. 1), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lai, M., Lim, C., & Wang, L. (2016). Potential of digital portfolios for establishing a professional learning community in higher education. Australian Journal of Educational Technology 32(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2572

Lin, T. J., Lin, T. C., Potvin, P., & Tsai, C. C. (2018). Research trends in science education from 2013 to 2017: a systematic content analysis of publications in selected journals. International Journal of Science Education, 41(3), 367-387.

Majola, X. M. (2023). Thinking ‘out of the box when designing formative assessment activities for the ePortfolio. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research, 5(3), 113-130.

Mapundu, M., & Musara, M. (2019). ePortfolios as a tool to enhance student learning experience and entrepreneurial skills. South African Journal of Higher Education, 33(6), 191-214.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development.

Mechouat, K. (2024). The impact of aligning Kolb’s experiential learning theory with a comprehensive teacher education model on preservice teachers’ attitudes and teaching practice. ESI Preprints (European Scientific Journal, ESJ), 20(28), 135–135.https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2024.v20n28p135

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Modise, M. E. P., & Mudau, P. K. (2023). Using ePortfolios for Meaningful Teaching and Learning in Distance Education in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 71(3), 286–298.

Modise, M. P. (2021). Postgraduate students’ perception of the use of ePortfolios as a teaching tool to support their learning in an open and distance education institution. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 283-297. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.508

Paulo Marinho, P., Fernandes, P., & Pimentel, P. (2021). The digital portfolio as an assessment strategy for learning in higher education. Distance Education, 42:2, 253-267 https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1911628

Michos, K., Cantieni, A., Schmid, R., Müller, L., & Petko, D. (2022). Examining the relationship between internship experiences, teaching enthusiasm, and teacher self-efficacy when using a mobile portfolio app. Teaching & Teacher Education, 109, 103570–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103570

Miranda, J., Navarrete, C., Noguez, J., Molina-Espinosa, J. M., Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., Navarro-Tuch, S. A., … & Molina, A. (2021). The core components of education 4.0 in higher education: Three case studies in engineering education. Computers & Electrical Engineering, 93, 107278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107278

Mudau, P. K., & Modise, M-E. P. (2022). Using ePortfolios for Active Student Engagement in the ODeL Environment. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 21, 425-438. https://doi.org/10.28945/5012

Nkalane, P. K. (2018). ePortfolio as an alternative assessment approach enhancing self-directed learning in an open distance learning environment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of South Africa.

Nielsen, T. (2024). Student teachers’ opportunities to learn through observation, own practice, and feedback on the practice while in field practice placements: a graphical model approach. Frontline Learning Research, 12(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v12i1.1347

Oakley, G., Pegrum, M., & Johnson, S. (2014). Introducing ePortfolios to pre-service teachers as tools for reflection and growth: lessons learnt. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 42(1):36–50.

Pelger, S., & Larsson, M. (2018). Advancement towards the scholarship of teaching and learning through the writing of teaching portfolios. International Journal for Academic Development.

Popova, A., Evans, D. K., Breeding, M. E., & Arancibia, V. (2022). Teacher professional development around the world: The gap between evidence and practice. World Bank Res. Observer 37, 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkab006

Saeed, M. A., Coleman, K., Jabbar, A., & Krekeler, N. (2020). Electronic portfolios for learning and teaching in veterinary education. The AAEEBL ePortfolio Review, 4 (1): 28–42. https://aaeebl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/AePR-v4n1

Sayed, Y., & Bulgrin, E. (2020). Teacher professional development and curriculum: Enhancing teacher professionalism in Africa. Education International. University of Sussex. https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.23478167.v1

Simatele, M. (2015). Enhancing the portability of employability skills using ePortfolios. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 39(6), 862–874.

Singh, M., & Mukeredzi, T. (2024). Teachers’ experiences of continuous professional development for citizenship and social cohesion in South Africa and Zimbabwe: enhancing capacity for deliberative democracies. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 9, p. 1326437). Frontiers Media SA. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1326437

Smith, N., & de Klerk, E. D. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions and policy directives for transformative teacher leadership initiatives during and beyond covid-19, School Leadership & Management, https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2022.2088490

Tan, C. P., Van der Molen, H. T., & Schmidt, H. G. (2017). A measure of professional identity development for professional education. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1504-1519. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1111322

UNESCO (2020). DRAFT SADC Regional Framework on Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers. Paris: UNESCO

Van Wyk, M. M. (2017). Exploring student teachers’ views on eportfolios as an empowering tool to enhance self-directed learning in an online teacher education course. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 42(6), 1-21.

Van Wyk, M. M. (2018). ePortfolio as an empowering tool in the teaching methodology of economics at an open distance e-learning university. Ubiquitous Learning: An International Journal, 11(3), 35-50. https://doi.org/10.18848/1835-9795/CGP/v11i03/35-50

Van Breda, M., & van Wyk, M. (2018). Electronic-portfolio approach to enhance self-directed learning. In Transnational perspectives on innovation in teaching and learning technologies (pp. 45-66). Brill.

Van Schalkwyk, S.C., Leibowitz, B.L., Herman, N., & Farmer, J.L. (2015). Reflections on professional learning: Choices, context, and culture. Studies in Educational Evaluation; 46: 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.03.002

Vorotnykova, I. P., & Zakhar, O. H. (2021). Teachers’ readiness to use ePortfolios. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 18:(1), https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v81i1.3943

Walland, E., & Shaw, S. (2022). ePortfolios in teaching, learning, and assessment: tensions in theory and praxis, Technology, Pedagogy, and Education, 31:3, 363–379, https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2022.2074087

Webster, R. S., & Whelen, J. D. (2019). The Importance of Rethinking Reflection and Ethics for Education. Rethinking Reflection and Ethics for Teachers, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9401-1_1

Yang, M., Wang, T., & Lim, C. P. (2023). ePortfolios as digital assessment tools in higher education. In Learning, Design, and Technology: An International Compendium of Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy (pp. 2213-2235). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Yeo, N., & Rowley, J. (2020). “Putting on a show’ non-placement will in the performing arts: Documenting professional rehearsal and performance using ePortfolio reflections,” Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, vol. 17, no. 4, preceding pp 1–17, 2020.

Zimmerman, B. (2011). Motivational sources and outcomes of self-regulated learning and performance. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 49–64). New York: Routledge.

Zegwaard, K. E., Pretti, T. J., Rowe, A. D., & Ferns, S. J. (2023). Defining work-integrated learning. In The Routledge international handbook of work-integrated learning (pp. 29-48). Routledge.

AUTHOR

Dr Aloysius Claudian Seherrie (ORCID: is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, College of Education, at the University of South Africa (UNISA). He has published extensively in high-impact journals, contributed to conference proceedings, and engaged in research exploring face-to-face educational practices. Before entering higher education, Dr Seherrie served as a Senior Education Specialist in the Northern Cape Department of Education, South Africa. His research in Curriculum Studies focuses on cooperative learning, self-directed learning (SDL), e-portfolios, teacher education, and the promotion of social justice in teaching and learning environments.

Email: seherac@unisa.ac.za