39 The Impact of the Adoption and Use of Artificial Intelligence on ePortfolios in Higher Education Institutions: A Digital Resilience Perspective

Hugo Lotriet

University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

The importance of digital resilience (DR) in higher education institutions (HEIs) was highlighted by the disruptions posed by the recent COVID-19 pandemic. HEIs were rapidly forced into emergency remote teaching (ERT), and those institutions with strong digital resilience (DR) weathered the shock more efficiently than other, less resilient institutions. The use of ePortfolios as an assessment method was highlighted as contributing to digital resilience.

A recent systemic disruption in education relates to the widespread adoption and use of artificial intelligence (AI). Although the benefits of AI adoption and use have been widely touted, the impact of AI in higher education contexts poses significant challenges to institutions, to the extent that AI could be considered a systemic ‘shock,’ thus having similar implications as, for example, the COVID-19 pandemic. This impacts DR in HEIs, also on specific aspects such as the adoption and use of ePortfolios.

This chapter critically considers the implications of AI for ePortfolios in HEIs from a DR perspective.

This chapter is therefore conceptual and presents a critical literature review that considers AI both as a shock and a potential enabler of the use of ePortfolios in terms of institutional and DR dimensions. Given the systemic nature of DR and ePortfolios, some suggestions on dealing with the impact of AI are presented from a systems perspective.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, ePortfolios, digital resilience, higher education institutions

INTRODUCTION

The recent COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of digital resilience (DR) in higher education institutions (HEIs). Institutions with higher levels of DR weathered the shock better, being able to adapt, recover, and transform more efficiently (Boh et al., 2023). The need for HEIs to rapidly adopt emergency remote teaching (ERT) also highlighted the need for appropriate teaching methods, practices, and tools and the contribution of these tools to DR. One such tool that has been discussed extensively is the ePortfolio, which was well-suited to the conditions of the pandemic because it encouraged and scaffolded self-regulated learning (Zhang & Tur, 2024), thus contributing to DR.

The rapid maturation of artificial intelligence (AI) tools in recent times and their rapid adoption and use (especially generative AI by learners) could also be conceptualised as a shock to HEIs, straining DR. As will be argued in more detail, AI has significant implications for ePortfolio adoption and use, with specific reference to the systemic elements of DR.

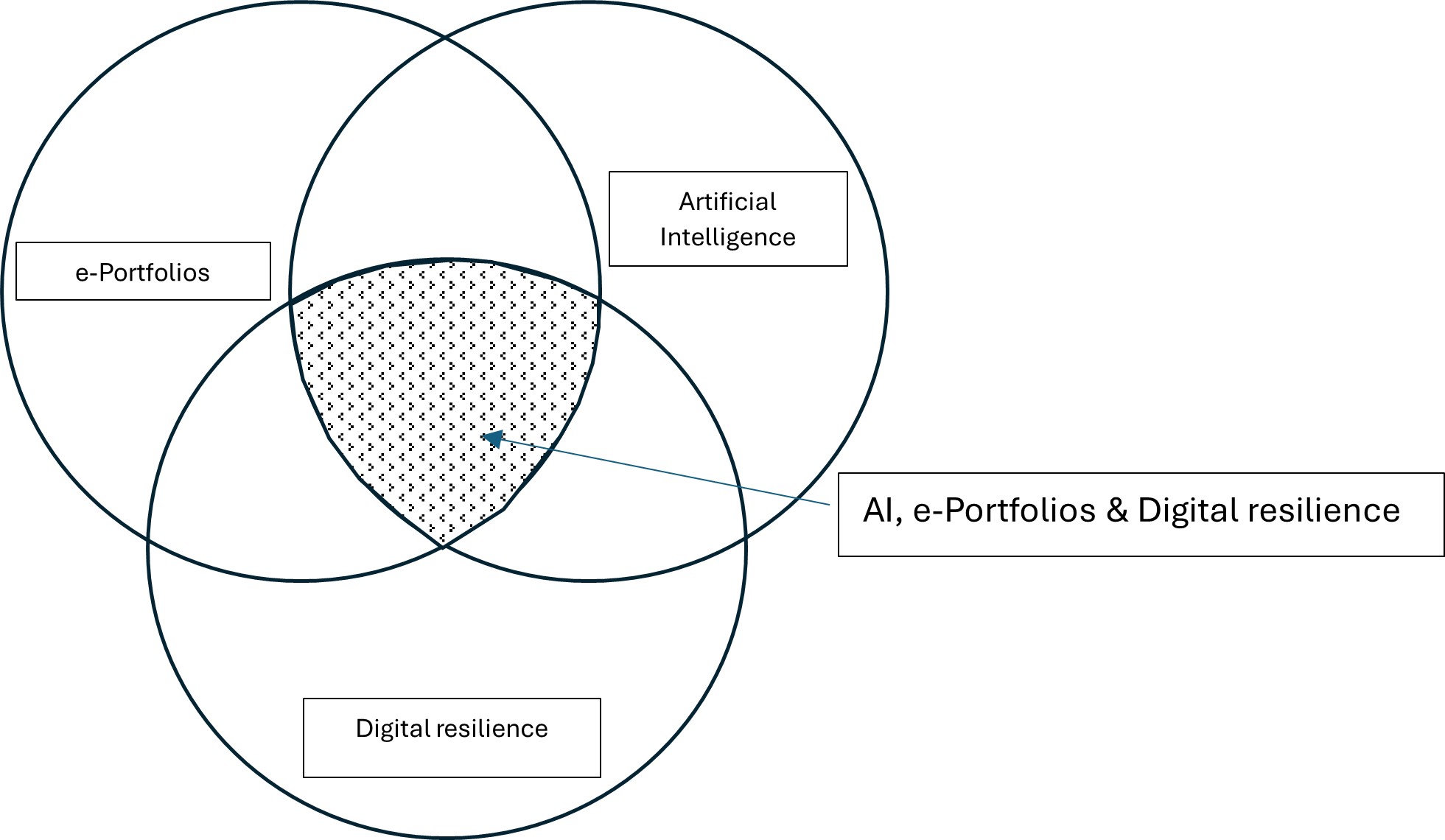

This paper contributes to discourses at the intersection of DR in HEIs, the emergence of AI, mainly as a shock but potentially also as an enabler, and the adoption and use of ePortfolios and DR in HEIs (see Figure 1). The chapter contributes by making explicit the implications of AI for ePortfolio use in terms of the systemic dimensions of institutional DR (Weller & Anderson, 2013) and individual DR (Sun et al., 2022). The chapter also contributes by making some suggestions on dealing with AI from the systems perspective proposed by Moore and Kearsley (2012) for online learning at HEIs.

The chapter has been structured as follows: First, disruptions (or shocks) and the nature of digital in HEIs are discussed; second, the adoption and use of ePortfolios in HEIs are considered; third, the nature of AI as a shock and potential enabler is discussed. Following this, explicit examples of the implications of AI as a shock and potential enabler for ePortfolio use are provided in terms of the dimensions of institutional and individual DR. Finally, some potentially important considerations for ensuring continued DR of HEIs related to the use of ePortfolios are suggested, using the systems view of online HEIs of Moore and Kearsley (2012).

Figure 1

Focus of this paper

DIGITAL DISRUPTIONS AND THE NATURE OF DR IN HEI

Digital disruptions or ‘shocks’

Although most organisations are regularly subjected to predictable disruptions (Liu et al., 2023), major systemic shocks have the potential to pose existential threats with longer-term consequences (Boh et al., 2023). The nature of these systemic shocks that impact organisational DR could be either natural or human-triggered (Boh et al., 2023). Examples of such disruptions are varied, as has been indicated by various authors (Boh et al., 2023; Malgonde et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2022), and may include wars and conflicts, medical crises (e.g., COVID-19), and economic shocks (e.g., economic recession or sudden high levels of unemployment, as were experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic). A major source of shocks originates from disruptions caused by information and other technologies (Sun et al., 2022). In this chapter, it is argued that despite its massive potential for beneficial use, AI at present constitutes such a shock for DR in the context of HEIs and the adoption of the use of ePortfolios.

The nature of DR in HEIs

Although the concept of resilience has been applied at various levels of analysis (Sun et al., 2022), such as individual, family, community, and country, Weller and Anderson (2013) argue that in the educational context, it applies especially at the institutional and individual levels. These two levels have therefore been adopted in this chapter and are discussed in more detail.

DR at the institutional level

In the context of education, Weller and Anderson (2013) adopt the concept of DR based on the resilience metaphor in ecology and, analogously, refer to the stability of education systems under conditions of change. Their conceptualisation of DR in terms of HEI institutions is also used in this chapter to structure the exposition of the impact of AI on HEIs with specific reference to ePortfolios. Their systemic dimensions of DR for HEIs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Institutional DR dimensions in HEIs (adapted from Weller & Anderson, 2013, p.59)

|

Resilience dimension

|

Description

|

|

Latitude: (Walker et al., 2004) |

Capacity of a system to change before undergoing a state change |

|

Resistance (to change) (Walker et al., 2004) |

The capacity of a system to resist external shocks |

|

Precariousness: (Walker et al., 2004) |

Closeness of systems to thresholds |

|

Panarchy (Walker et al., 2004) |

Impact of (cross-level) forces at different scales and levels between various systems |

|

Diversity (Hopkins, 2009) |

The multiple options and approaches available within systems to deal with shocks |

|

Modularity (Hopkins, 2009) |

Self-reliance of subsystems in times of systemic shocks |

|

Tightness of feedback (Walker et al., 2004) |

Effectiveness of systems responses to changes |

The significance of DR was highlighted by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated rapid changes in operations in HEIs, as these organisations were some of the worst affected by the crisis and had to resort at very short notice to emergency remote teaching (ERT) (Park et al., 2023).

Weller & Anderson (2013) argue (from a systemic perspective) for the importance of function over form, i.e., the ability in academic institutions to maintain operational stability under conditions where challenges and adversity (i.e., change) occur in practice. This implies an evolution that takes place while retaining essentiality (Weller & Anderson, 2013). In practice, the implication is for organisations to have capabilities that enable the continuation of high-quality customer service, even during crisis conditions (Park et al., 2023).

DR at the individual level

There is a vast body of literature on individual resilience (Eri et al., 2021). At an individual level, Sun et al. (2022) conceptualise the notion of DR as “a circular process toward greater performance and function in the form of understanding, knowing, learning, and moving forward when facing stressors, challenges, or adversity” (Sun et al., 2022, p. 1). DR thus relates to human behaviour combined with the effective adoption and use of technologies and implies a level of digital literacy at the individual level (Sun et al., 2022).

Although various frameworks that could inform individual DR have been published, e.g., Eri et al. (2021), for the purpose of this chapter, the framework proposed by Sun et al. (2022) has been adopted to structure the dimensions of digital resistance. Dimensions include (1) understanding the nature of digital shocks; (2) knowledge and critical thinking that enable individuals to deal with shocks and disruptions; (3) acquisition of appropriate digital skills; and (4) self-efficacy as a means of moving forward.

THE USE OF EPORTFOLIOS IN HIGHER EDUCATION

Characteristics and functionality of ePortfolios

The UK Joint Information Systems Committee provides the following definition for ePortfolios: “[An] ePortfolio can be used to refer to a system or a collection of tools that support ePortfolio-related processes (such as collection, reflection, annotation, etc.). The term ‘ePortfolio’ can also refer to the products emerging through these systems or tools. It is helpful to think about the purposes to which learners might put their ePortfolios (for example, presentation for assessment, to support transition, or to support and guide learning.” (Joint Information Systems Committee, 2008, p. 3). Chatham-Carpenter et al. (2010) conceptualise ePortfolios as a fusion between education and technology. ePortfolios could therefore be seen as (information) systems (IS) focused on fostering engagement and collaboration (Gorbunovs, 2011; Gorbunovs et al., 2013). The IS characteristics of ePortfolios have implications for AI-based ePortfolios in terms of DR, as will be discussed later in the chapter.

In terms of functionality Ciesielkiewicz (2019) broadly categorises ePortfolios as contributing to the areas of learning, assessment and further (career) development. Chatham-Carter et al. (2010) also refer to the potential of the ePortfolio in terms of programme reviews, and usefulness for institutions to demonstrate adherence to professional standards. Both studies consider ePortfolios to be a 21st-century tool.

ePortfolios and Learning

Modise (2021) argues that important elements of ePortfolios include “… assessment, feedback, interaction, reflection, learning process, and the showcasing or sharing of students’ artefacts…” (Modise, 2021, p. 285). From an educational perspective, the use of portfolios has various advantages, including the potential to improve student engagement (if properly implemented), active learning, documentation of learning over extended time periods, and applicability across a wide variety of disciplines (Mudau & Modise, 2022).

Furthermore, the value lies in the facilitation of self-directed learning and associated learning skills (Ciesielkiewicz, 2019; Tekyan & Yudkowsky, 2009), such as (lifelong) reflection skills (Chatham-Carpenter et al., 2010). This also implies that students can take ownership of their own learning experience (Chatham-Carpenter et al., 2010).

An important element of higher education is the provision of opportunities for reflective learning. Reflection in the learning environment could happen at various levels, but essentially relates to knowledge growth and transformation through reflective thinking, the formal reflective process being part of outcomes of programmes and assessment requirements (Ryan & Ryan, 2013).

For ePortfolios, the ability to collect a diversity of evidence in a diversity of formats allows for ‘triangulated’ evidence of not only knowledge but also competent performance (Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009). The triangulation allows for a reduction in assessment bias (Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009, op. cit.). ePortfolios can be applied both for formative and summative assessments and self-assessment. An additional educational advantage of using portfolios is the continuous assessment of skills, which may stretch over years, thus enabling the use of ePortfolios for professional development (Tekyan & Yudkowsky, 2009).

For career development, continuing the ePortfolio after graduation and allowing potential employers access may assist in evaluation processes for potential employment (Ciesielkiewicz, 2019). Both during and after HEI education, the tool is a means to showcase various skills, training, and experience, among others (Chatham-Carpenter et al., 2010).

ePortfolio Vulnerabilities

It nevertheless needs to be noted that portfolios do have vulnerabilities (Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009). Creating ePortfolios is complex, and all involved parties (students and teachers) must be adequately trained (Ciesielkiewicz, 2019). Structures of ePortfolios can be challenging, and a balance needs to be found between prescriptive structures and allowing various degrees of flexibility to learners (Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009). An extensive and stable information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure is needed to host ePortfolios (Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009). The complexity of AI requires even more complex infrastructures, and any lapses in this infrastructure may create challenges in using ePortfolios. Furthermore, it goes without saying that for ePortfolios, digital access needs to be adequate (Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009), which is still an issue in developing countries. These vulnerabilities are also significant regarding the potential shock posed by AI.

ePortfolios and DR

The significance and value of ePortfolios became especially visible during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the ability to facilitate a rapid move to online learning and assessment, with the ePortfolio thus becoming a vital tool due to its potential in terms of self-regulated learning (Zhang & Tur, 2024). As an online tool, the ePortfolio was aligned with self-regulated, reflective, and collaborative learning, flexibility, and demonstrability of continuous learning (Zhang & Tur, 2024), thus contributing to DR. However, challenges remained related to “sufficient guidance, support, privacy, and plagiarism” (Zhang & Tur, 2024, p. 429), and issues related to accessibility and insufficient support systems would have been detrimental to DR. At individual levels of DR, the contribution by ePortfolios to increased digital literacy skills and 21st-century skills such as problem-solving skills is significant (Zhang & Tur, 2024).

ePortfolios and AI

The complexity of AI systems requires significant efforts to put meaningful, well-purposed systems in place to serve the specific needs of ePortfolios; some examples are provided by Gantikow et al. (2023). As a result of this complexity, the potential harnessing of AI to support educational purposes at universities (such as for ePortfolios) is still largely aspirational rather than implemented and in full use (Ruano-Borbolan, 2025).

A significant aspect of the challenges facing assessment in the presence of AI is student access to powerful, commercially available AI tools. Student use of, for instance, generative AI to complete assessments not only skews the ability to assess the actual levels of learning achieved but also the ability to analyse learning data (Riegel, 2024).

THE DUAL NATURE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

In this section, the dual nature of AI is highlighted. There is potential for AI to be both a shock and an enabler in the context of ePortfolios and HEIs. However, it is argued that AI currently exhibits the characteristics of a shock more than those of an enabler.

AI as a disruptor or shock that impacts DR

Analogously to the COVID-19 pandemic, the following dimensions could be considered in terms of defining AI as a shock (Boh et al., 2023):

Does AI create uncertainty? The significant transformative potential of education by AI, which would probably require significant paradigm shifts by educators around all aspects of education, creates uncertainty in teachers on how to incorporate AI in their teaching practices and on ways to deal with unauthorised use of AI by learners (Looi, 2024). It has also been documented that AI creates uncertainty in learners around awareness and expectations of the benefits, risks and limitations that could be associated with the adoption and use of AI (Akhras, 2024).

Does dealing with AI require rapid and “unusual” expansion of resources and capabilities? Current findings indicate that this is indeed the case, with requirements for rapidly expanding computational abilities (Pilz et al., 2025) and infrastructure expansion (e.g., data centres, networks, and specialised computer hardware), but also vast amounts of natural resources such as water and electricity (Robbins & Van Wynsberghe, 2022).

Does dealing with AI require the development of novel organisational capabilities? Weber et al. (2023) argue that specific capabilities are required to deal with the unique challenges posed by AI and that these are significant for successful AI implementation. These capabilities relate to the need for practices to enhance transparency of AI (project planning and co-development) and data and model management for AI systems.

Therefore, in terms of the dimensions of Boh et al. (2023), it could be seen that AI essentially acts as a systemic shock, in many ways analogous to the COVID-19 pandemic.

AI as a Potential Enabler

For AI to be used as an efficient enabler in HEI, the characteristics of AI as technology must be considered. These include the characteristics of ‘namability’ (objects that can be named are virtually limitless in digital terms), calculability (which allows for the automation of large numbers of routine steps), measurability (enabled through sensors or labelling), and representability (material meaning making) (Cope et al., 2021). The ultimate potential strength of AI thus lies in the intersection of these characteristics, i.e., rapid counting and calculation related to (digitally) tagged objects obtained from sensors or labelling.

According to Cope et al. (2021, op. cit.), the implications for educational applications of AI are the following: (1) The essential nature of AI means that it cannot replace humans (e.g., teachers); (2) All aspects of a digitally mediated learning process can be tagged and sensed, thus allowing for AI-enabled continuous feedback loops; (3) Ontologies used in AI systems could allow for interoperability between various HEI systems and disciplinary domains and the ability to look up ‘tagged’ knowledge; (4) Calculability allows, for example, for computer-based coordination of complex peer review processes and statistical analysis of texts (e.g., large-language models); Measurability allows for continuous sensing related to learning processes and providing feedback on what was measured, while representation allows for more extensive and complete knowledge representation across different formats (e.g., texts, speech, video).

It should therefore be clear that the ability for AI to enhance the use of ePortfolios is potentially vast, e.g., in terms of supporting continuous assessment and feedback, improved peer interaction, and cross-domain and interdisciplinary application of ePortfolios. As previously stated, these abilities are mostly not yet fully exploited in HEIs (Ruano-Borbalan, 2025). However, the ease of use of generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT) has resulted in widespread adoption by students (McDonald et al., 2025) and other role players in education.

Given that the enabling aspects of AI are not yet fully realised, I would consider AI to be predominantly a systemic shock to DR. The implications of this are set out in more detail in the following sections.

THE POTENTIAL IMPACT OF AI ON THE USE OF EPORTFOLIOS IN HIGHER EDUCATION IN TERMS OF DR

The application of AI in higher education has been extensively discussed in the literature. Zawacki-Richter et al. (2019) categorize the nature of AI applications in HEI as “…adaptive systems and personalisation…, assessment and evaluation…, profiling and prediction, and …intelligent tutoring systems” (p. 11). It should be clear that each of these categories has potential implications for ePortfolios.

It was mentioned earlier in the chapter that ePortfolios exhibit characteristics of sociotechnical information systems. The complex nature of information systems inherently has vulnerabilities (Schemmer et al., 2021), which means that careful consideration should be given to the DR of such systems in the presence of shocks. If this is well executed, such systems could increase the overall DR of organisations (Schemmer et al., 2021, op. cit.).

In this section, the implications of AI as a systemic shock in terms of ePortfolios in HEIs are considered in terms of institutional characteristics of DR systems (Weller & Anderson, 2013) and individual DR (Sun et al., 2022).

AI as a Disruptor of ePortfolio Adoption and Use

Tables 2 and 3 show examples of the impact of AI as a shock on various elements of DR (institutional and individual) with specific reference to the use of ePortfolios in HEIs.

Table 2

AI as a disruptor of ePortfolio adoption and use in terms of DR dimensions (created by Author)

|

DR dimension (Weller & Anderson, 2013) |

Examples of AI as ePortfolio disruptor (shock) |

|

Latitude |

– If HEIs do not manage the technology transitions associated with AI well, that is, ultimately establishing functional ‘smart’ campuses (Agbehadji et al., 2021; George & Wooden, 2023), this can compromise latitude. – AI may lead to changes in the assessment of ePortfolios, while higher education institutional readiness (and adoption) may be lagging (Ruano-Borbalan, 2025), thus reducing latitude. – Inherent biases in AI may negatively impact assessment practices (Chinta et al., 2024) and disrupt the normal use of ePortfolios by learners and teachers. |

|

Resistance |

– Fragmented implementation of AI by HEIs (Patel & Ragolane, 2024) may impact the implementation of ePortfolios, potentially resulting in vulnerabilities. – Validity and reliability of portfolios are important (Jenkins et al., 2013). Extensive (uncritical) student use of AI can negatively impact both these characteristics. |

|

Precariousness |

– A significant concern relates to the impact of generative AI on academic integrity (Rodrigues et al., 2025). – HEIs with inadequate digital infrastructure could struggle with the integration of AI (Patel & Ragolane, 2024). |

|

Panarchy |

– Fragmented approaches to AI implementation in HEIs may lead to inconsistent applications and integration (Patel & Ragolane, 2024), which in turn could disrupt the methods of assessment of ePortfolios in HEIs. – There may be resistance at different levels to the adoption and use of AI applications (Agbehadji et al., 2021). |

|

Diversity |

– Inherent bias in AI systems may have a negative impact (Swiecki et al., 2022) on the assessment of ePortfolios of minority and other marginalised groups. – AI personalisation may not be authentic in terms of considering unique student contexts (personal, cultural, and community) (Saltman, 2020), which has the potential to reduce true diversity in the use of ePortfolios. – Unequal resource distribution required for universities to implement AI systems can widen the digital divide (Jin et al., 2025), also with reference to adoption and use of ePortfolios. |

|

Modularity |

– Overreliance on AI-based practices (including assessment) can negatively impact critical reflective and creative abilities of students, as well as their independence (agency and self-regulation) (Darvishi et al., 2024; Jin et al., 2025). Overreliance on AI-based practices can negate educator experience and expertise (Swiecki et al., 2022). – Established teaching and learning methods (such as ePortfolios) may be affected if AI systems disrupt perceptions of teacher authority (or status) (which may not be entirely detrimental) (Selwyn, 2019). – Systemic failure of the complex digital infrastructure and organisational capabilities required for AI-supported systems (Holmström, 2022) may compromise the ability for students to undertake independent AI-supported activities related to regard to their ePortfolios The capacity for AI to store and analyse massive datasets raises education-related ethical issues (Mayfield et al., 2019), notably around autonomy of learners, marginalised groups, and HEIs. |

|

Tightness of feedback loops |

– Biases in AI-generated feedback (Riegel, 2024) on ePortfolios can affect the effectiveness and impact of ePortfolios. – The organisational capabilities required for the implementation of AI are extremely complex and difficult in terms of infrastructure, staffing, processes, and decisions (Holmström, 2022). Instabilities in these organisational capabilities and digital infrastructure required for AI supported operations may impact on ePortfolio related feedback loops. |

Table 3

Individual DR in terms of the dimensions (adapted from Sun et al., 2022, n.p.)

|

Individual DR element (Sun et al., 2022)

|

Examples of AI as potential shock (disruptor)

|

|

Understanding the nature of digital shocks |

Teachers may not understand the true nature of potential AI-related threats to their learning activities (Velander et al., 2024). This also applies to learners and other role-players. |

|

Knowledge and critical thinking that enable individuals to deal with shocks and disruptions |

Teachers (and learners) may not have the critical thinking skills to establish the appropriateness of various resources and skills to deal with AI-related disruptions (Alqarni, 2025). |

|

Acquiring the appropriate digital skills |

Teachers may not have sufficient digital knowledge and skills to deal with AI appropriately (Sperling et al., 2024). This would also apply to learners and other role players. |

|

Self-efficacy as a means of moving on |

AI has the potential to cause anxiety in learners (Khan et al., 2025) and teachers (Velander et al., 2024) |

From these tables, it may be deduced that AI as a disruptor has potential impacts on all elements of systemic DR. It may disrupt tuition and learning, supporting systems, and role players such as teachers and learners. Dealing with these disruptions requires a systemic approach, which is discussed in further sections.

AI as a potential enabler in the use of ePortfolios in HEIs

It has been noted that at present, the potential of AI to support HEI operations is still largely aspirational, with limited implementation (Ruano-Borbalan, 2025) and a lot of ’hype’ being created (Stine et al., 2019). The potential of AI as an enabler, with specific reference to ePortfolios in HEIs institutionally and individually, is set out in more detail in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4

AI as a potential ePortfolio enabler viewed in terms of the dimensions of DR (created by Author)

|

DR element (Weller & Anderson, 2013) |

Examples of AI as a potential ePortfolio enabler |

|

Latitude |

– The potential of AI to support dynamic changes in student learning paths could increase overall flexibility (Cope et al., 2021). – The analytical and predictive abilities of AI would allow for proactive measures where student or staff performance is inadequate (Cope et al., 2021). |

|

Resistance |

– Carefully considered selective adoption of AI to strengthen pedagogies and assessment methods may be beneficial (Lee, 2023). -(Organisational) control over AI-based data harvesting is of crucial importance (Williams, 2019) to support increased resistance and, therefore, DR. Linked to this is the importance of the establishment of strong ethical foundations for the use of AI in HEIs (Jin et al., 2025), also for ePortfolios. |

|

Precariousness |

– AI analytics can support early interventions where student performance is lacking (Cope et al., 2021). – Similarly, AI analytics can identify where there are issues in ePortfolio adoption and use, for instance, related to both cognitive and affective aspects of the learning processes (Swiecki et al., 2022), thus enabling early interventions. |

|

Panarchy |

– AI-supported assessment can offer scalability of online learning across departments and programmes (Cai et al., 2024). – AI can enable data exchanges among all role players across all levels of the HEI and its environment, furthering career opportunities for learners (Stine et al., 2019). |

|

Diversity |

– AI-supported ePortfolios have potential for enhanced individualisation in terms of learning and assessment experiences (Swiecki et al., 2022). – Given the reflective nature of ePortfolios, language use is important (Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009). The language and translation capabilities of AI allow for improved language use and the inclusion of diverse languages, thus also potentially promoting diversity in collaboration among staff and students. – A wide diversity of recordable information can be included (Cope et al., 2021) in ePortfolios. |

|

Modularity |

– AI-supported ePortfolios have potential for increased student independence (Sufyan Ghaleb & Alshiha, 2023), e.g., through decentralisation of progress tracking, skills development, feedback, and peer interaction processes in peer knowledge networks (Cope et al., 2021). AI tools may improve the autonomy and self-directed behaviour of teachers if this element is included in professional development (Duan & Zhao, 2024).

|

|

Tightness of feedback |

AI-supported ePortfolios can support feedback to learners, thus improving feedback cycles and speed of feedback (Barnes & Hutson, 2024; Owoc et al., 2019). AI-based skills tracking and analysis of ePortfolios can result in timely suggestions in terms of personal learning pathways and skills development (Cope et al., 2021). |

Table 5

AI viewed as a potential enabler in terms of the dimensions of individual resilience (Sun et al., 2022, n.p.)

|

DR dimension (Sun et al., 2022) |

Examples of AI as a potential individual DR enabler |

|

Understanding the nature of digital shocks |

Enhanced understanding of ePortfolio-related risks such as cybersecurity, hardware and accessibility issues, and skills requirements (McAlpine, 2005) could be achieved through the application of generative AI. |

|

Knowledge and critical thinking that enable individuals to deal with shocks and disruptions |

AI-based systems have the potential to be trained to focus on higher-order (critical) thinking skills (Cope et al., 2021). |

|

Acquiring the appropriate digital skills |

AI methods can assist with high-quality assessment of digital skills across institutions (Yang, 2023) |

|

Self-efficacy as a means of moving on |

AI can contribute to self-efficacy, self-management, and self-directed learning (Ghaleb & Al Shihah, 2023) |

From these tables, it should be noted that there is significant potential in AI to support DR in ePortfolio adoption and use. However, careful management of all aspects would be a requirement. This is discussed in more detail in the following section.

SUGGESTED WAYS FORWARD TO ADDRESS THE IDENTIFIED CHALLENGES

Because DR is a systemic phenomenon, considerations around addressing AI as a systemic shock should preferably be undertaken from a holistic (systems) perspective (Schemmer et al., 2021). For an educational system such as AI-supported ePortfolios, the familiar systems conceptualisation of Moore and Kearsley (2012) of (distance) education as a system is used. The elements of this system view include the institution, course design, course delivery (including media and technology), teachers, learners, and management (Moore & Kearsley, 2012).

Table 6

Considering the way forward in the context of AI and ePortfolios: A systems view (adapted from Moore & Kearsley, 2012, p.47)

|

System element or subsystem (Moore & Kearsley, 2012) |

Implications for AI and ePortfolios in the context of DR |

|

Management |

Ensure that institutional policies, processes, and capabilities related to assessment (and therefore ePortfolios) consider the realities of AI (Chan, 2023). |

|

Teaching |

– It must be ensured that role players are prepared to deal with AI in the context of ePortfolios (Schemmer et al., 2021), especially teachers as key role players (Ciesielkiewicz, 2019). Educators will adopt technology and become agents of change if they can see clear benefits in terms of solving a persistent challenge (Van Tartwijk & Driessen). – All AI systems need to be human-centred (Yang et al., 2021) and structured to allow human control (whether teachers or learners) and to ensure the continuance of meaningful human engagement between teachers, learners, and others around ePortfolios, even in the presence of AI. – Careful consideration should be given to the preservation of academic integrity in the face of the potential threats posed by AI (Rodrigues et al., 2025). – It must be ensured that assessment through ePortfolios remains an ‘authentic’ evaluation (Jin et al., 2025). – The requirements for ePortfolios that increase student engagement (Mudau & Modise, 2022) should be carefully considered, given the presence of AI. – Teacher training should include the implications of AI (Zhang & Zhang, 2024), also for ePortfolios |

|

Learning |

– Students must be prepared to prioritise critical thinking and reflection (Riegel, 2024) and have strong ethical roots, especially in the face of the capabilities of AI. – A strong focus must be placed on student digital literacy, which would include AI literacy and awareness (Chiu et al., 2024). |

|

Program design |

– The implications of the availability of AI in terms of the format, structure, and processes of assessment must be considered (Swiecki et al., 2022). – The implications of AI-enabled ePortfolios in terms of reputation, quality, and accreditation of programmes must be considered (Hassan, 2025). |

|

Technology |

The scalability of infrastructure (Schemmer et al., 2021). Central technical support is critical for both staff and students (Ciesielkiewicz, 2019). |

|

Education system (context) |

– HEIs need to engage with government and other role players on the changing landscape of assessment and higher education (Fitzgerald et al., 2023) – Government must consider appropriate regulatory and policy frameworks that deal with AI and its implications for higher education (Mahrishi et al., 2025). |

CONCLUSIONS

This chapter focused on the impact of AI on ePortfolios and DR in the context of HEIs. It was argued that AI at present constitutes predominantly a systemic shock, but also a potential enabler, which impacts aspects of DR related to ePortfolio adoption and use at both institutional and individual levels. Examples of the potential impacts were shown. The chapter thus contributes to scholarly discourses at the intersection of the adoption and use of AI, the use of ePortfolios, and digital resilience in higher education institutions. The specific contributions that were made include making explicit the implications of AI for ePortfolio use in terms of the systemic dimensions of institutional DR (Weller & Anderson, 2013) and individual DR (Sun et al., 2022). The chapter also contributes by making suggestions on dealing with AI from the systems perspective proposed by Moore and Kearsley (2012) for education in HEIs. Specifically, it is argued that dealing with AI and ePortfolios in a digitally resilient manner requires a holistic approach, involving all systems and subsystems involved in teaching and learning at the HEI level, as well as all role players (teachers, learners, managers, administrators, and others).

More empirical research and case studies are needed to understand all aspects of the practical implications of AI in the context of ePortfolios and DR.

REFERENCES

Agbehadji, I. E., Millham, R. C., Awuzie, B. O., & Ngowi, A. B. (2021, November). Stakeholder’s perspective of digital technologies and platforms towards smart campus transition: Challenges and prospects. In S. Mishra, J. Oluranti, & R. Damaševičius (Eds.), Informatics and Intelligent Applications. Communications in Computer and Information Sciences: Vol. 1547 (pp. 197-213). Springer International Publishing.

Alqarni, A. (2025). Artificial Intelligence—Critical Pedagogic: Design and Psychologic Validation of a Teacher‐Specific Scale for Enhancing Critical Thinking in Classrooms. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 41(3), e70039. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.70039

Akhras, C. (2024). Addressing Academic Uncertainty: Traditional Learning in the Middle East Versus Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Far East. In M. Lahby, Y. Maleh, A. Bucchiarone, & S.E. Schaeffer (Eds.) General Aspects of Applying Generative AI in Higher Education (pp. 281-297). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-65691-0_15

Barnes, E., & Hutson, J. (2024). Strategic integration of AI in higher education and industry: The AI8-point model. Advances in Social Sciences and Management, 2(6), 39-52. https://doi.org/10.63002/assm.26.520

Boh, W., Constantinides, P., Padmanabhan, B., & Viswanathan, S. (2023). Building digital resilience against major shocks. MIS Quarterly, 47(1), 343-360.

Cai, C., Zhu, G., & Ma, M. (2024). A systemic review of AI for interdisciplinary learning: Application contexts, roles, and influences. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 9641-9687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13193-x

Chan, C. K. Y. (2023). A comprehensive AI policy education framework for university teaching and learning. International journal of educational technology in higher education, 20(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00408-3

Chatham-Carpenter, A., Seawel, L., & Raschig, J. (2010). Avoiding the pitfalls: Current practices and recommendations for ePortfolios in higher education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 38(4), 437-456. https://doi.org/10.2190/ET.38.4.e

Chiu, T. K., Ahmad, Z., Ismailov, M., & Sanusi, I. T. (2024). What are artificial intelligence literacy and competency? A comprehensive framework to support them. Computers and Education Open, 6, 100171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100171

Chinta, S. V., Wang, Z., Yin, Z., Hoang, N., Gonzalez, M., Quy, T. L., & Zhang, W. (2024). FairAIED: Navigating fairness, bias, and ethics in educational AI applications. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.18745

Ciesielkiewicz, M. (2019). The use of ePortfolios in higher education: From the students’ perspective. Issues in Educational Research, 29(3), 649-667.

Cope, B., Kalantzis, M., & Searsmith, D. (2021). Artificial intelligence for education: Knowledge and its assessment in AI-enabled learning ecologies. Educational philosophy and theory, 53(12), 1229-1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1728732

Darvishi, A., Khosravi, H., Sadiq, S., Gašević, D. &Siemens, G. (2024). Impact of AI assistance on student agency. Computers & Education, 210(2024), 104967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100171

Duan, H., & Zhao, W. (2024). The effects of educational artificial intelligence-powered applications on teachers’ perceived autonomy, professional development for online teaching, and digital burnout. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 25(3), 57-76. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v25i3.7659

Eri, R., Gudimetla, P., Star, S., Rowlands, J., Girgla, A., To, L., Li, F., Sochea, N., & Bindal, U. (2021). Digital resilience in higher education in response to COVID-19 pandemic: Student Perceptions from Asia and Australia. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(5), 7. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.5.7

Fitzgerald, H. E., Karen, B., Sonka, S. T., Furco, A., & Swanson, L. (2023). The centrality of engagement in higher education. In L.R. Sandmann & D.O. Jones (Eds.). Building the field of higher education engagement (pp. 201-219). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003443353

Gantikow, A., Isking, A., Libbrecht, P., Müller, W., & Rebholz, S. (2023). On the Creation of Classifiers to Support Assessment of ePortfolios. In D. D’Auria, M. Ge, M. Sert, V. Swaminathan, & T. Yamashaki (Eds.) Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM) (pp. 297-302). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISM59092.2023.00057

George, B., & Wooden, O. (2023). Managing the strategic transformation of higher education through artificial intelligence. Administrative Sciences, 13(9), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13090196

Gorbunovs, A. (2011). Design of the ePortfolio System’s Model with Artificial Intelligence Traits. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT 2011). IEEE Jordan Section.

Gorbunovs, A., Kapenieks, A., & Kudina, I. (2013). Competence development in a combined assessment and collaborative ePortfolio information system. Procedia Computer Science, 26, 79-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2013.12.009

Hassan, Z. Y. (2025). AI-Driven Horizons: Shaping the Future of Global Quality Assurance in Higher Education. In P.A. Okebukola (Ed.) Handbook on artificial intelligence and quality higher education. Vol. 3, AI and ethics, academic integrity and the future of quality assurance in higher education (105). Sterling Publishers.

Holmström, J. (2022). From AI to digital transformation: The AI readiness framework. Business Horizons, 65(3), 329-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2021.03.006

Hopkins, R. (2009). Resilience Thinking. Resurgence, 25712 – 15.

Jenkins, L., Mash, B., & Derese, A. (2013). Reliability testing of a portfolio assessment tool for postgraduate family medicine training in South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 5(1), 1-9. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC146976

Jin, Y., Yan, L., Echeverria, V., Gašević, D., & Martinez-Maldonado, R. (2025). Generative AI in higher education: A global perspective of institutional adoption policies and guidelines. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100348

Joint Information Systems Committee. (2008). Effective practice with ePortfolios: Supporting 21st century learning. http:// repository.jisc.ac.uk/5997/1/effectivepracticeeportfolios.pdf

Khan, K., Aziz, M. U., Minhas, M., & Khan, A. I. (2025). The Psychological Effects of AI-Based Learning on Student Motivation, Anxiety, and Cognitive Load. The Critical Review of Social Sciences Studies, 3(1), 3527-3540. https://doi.org/10.59075/1fvs0v71

Lee, A. V. Y. (2023). Supporting students’ generation of feedback in large-scale online courses with artificial intelligence-enabled evaluation. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 77, 101250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2023.101250

Looi, C. K. (2024). Charting the uncertain future of AI and education: promises, challenges and opportunities. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 19(3), 477-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2024.2379776

Liu, Y., Xu, X., Yong, J. & Deng, H. (2023). Understanding the digital resilience of physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: An empirical study. MIS Quarterly, 47(1), 391-422. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2022/17248

Mahrishi, M., Abbas, A., & Siddiqui, M. K. (2025). Global initiatives towards regulatory frameworks for artificial intelligence (AI) in higher education. Digital Government: Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1145/3672462

Malgonde, O.S., Saldanha, T.J.V., Mithas, S. (2023). Resilience in the open source software community: How pandemic and unemployment shocks influence contributions of others’ and one’s own projects. MIS Quarterly, 47(1), 361 – 390. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2022/17256

Mayfield, E. Madaio, M., Prabhumoye, S., Gerritsen, D. McLaughlin, B., Dixon-Román, E., & Black, A.W. (2019). Equity Beyond Bias in Language Technologies for Education. In H. Yannakoudakis, E, Kochmar, C. Leacock, N. Mandani, I. Pilán, T. Zesch (Eds.) Proceedings of the Fourteenth Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications, (444–460). Association for Computational Linguistics.

McAlpine, M. (2005). ePortfolios and Digital Identity: Some Issues for discussion. E-Learning, 2(4), 378 – 387. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2005.2.4.378

McDonald, N., Johri, A., Ali, A., & Collier, A. H. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence in higher education: Evidence from an analysis of institutional policies and guidelines. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 3, 100121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2025.100121

Modise, M. P. (2021). Postgraduate students’ perception of the use of ePortfolios as a teaching tool to support their learning in an open and distance education institution. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 283-297. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v8i2.508

Moore, M.G. & Kearsley, G. (2012). Distance Education: A Systems View of Online Learning (3rd ed.). Wadsworth.

Mudau, P. K., & Modise, M. P. (2022). Using ePortfolios for Active Student Engagement in the ODeL Environment. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 21, 425–438. https://doi.org/10.28945/5012

Owoc, M. L., Sawicka, A., & Weichbroth, P. (2019, August). Artificial intelligence technologies in education: benefits, challenges, and strategies of implementation. In M.L. Owoc & M. Pondel (Eds.) Artificial Intelligence for Knowledge Management (37-58). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85001-2

Park, J., Son, Y., & Angst, C. M. (2023). The Value of Centralized IT in Building Resilience During Crises: Evidence from US Higher Education’s Transition to Emergency Remote Teaching. MIS Quarterly, 47(1), 451-482. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2022/17265

Patel, S., & Ragolane, M. (2024). The implementation of artificial intelligence in South African higher education institutions: Opportunities and challenges. Technium Education and Humanities, 9, 51-65. https://doi.org/10.47577/teh.v9i.11452

Pilz, K.F., Mahmood, Y. & Heim, L. (2025). AI’s Power Requirements under Exponential Growth. Rand Corporation. Santa Monica, California. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3572-1.html

Rodrigues, M., Silva, R., Borges, A. P., Franco, M., & Oliveira, C. (2025). Artificial intelligence: Threat or asset to academic integrity? A bibliometric analysis. Kybernetes, 54(5), 2939-2970. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-09-2023-1666

Ruano-Borbalan, J. C. (2025). The transformative impact of artificial intelligence on higher education: A critical reflection on current trends and future directions. International Journal of Chinese Education, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2212585X251319364

Riegel, C. (2024). Leveraging Online Formative Assessments Within the Evolving Landscape of Artificial Intelligence in Education. In M. Sahin & D. Ifenthaler (Eds.). Assessment Analytics in Education: Designs, Methods, and Solutions (pp. 355-371). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-56365-2_18

Robbins, S., & Van Wynsberghe, A. (2022). Our new artificial intelligence infrastructure: becoming locked into an unsustainable future. Sustainability, 14(8), 4829. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084829

Ryan, M., & Ryan, M. (2013). Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(2), 244-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.661704

Saltman, K. (2020). Artificial intelligence and the technological turn of public education privatization: In defence of democratic education. London Review of Education, 18(2), 196-208. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.18.2.04

Schemmer, M., Heinz, D., Baier, L., Vössing, M., & Kühl, N. (2021). Conceptualizing Digital Resilience for AI-Based Information Systems. In ECIS 2021 Proceedings: Human Values Crisis in a Digitizing World.

Selwyn, N. (2019). Should robots replace teachers? AI and the future of education. Polity Press.

Sperling, K., Stenberg, C. J., McGrath, C., Åkerfeldt, A., Heintz, F., & Stenliden, L. (2024). In search of artificial intelligence (AI) literacy in teacher education: A scoping review. Computers and Education Open, 6, 100169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2024.100169

Stine, J., Trumbore, A., Woll, T., & Sambucetti, H. (2019). Implications of artificial intelligence on business schools and lifelong learning. Academic Leadership Group. https://uniconexed.org/research/implications-of-artificial-intelligence-on-business-schools-and-lifelong-learning/

Sufyan Ghaleb, M. M., & Alshiha, A. A. (2023). Empowering Self-Management: Unveiling the Impact of Artificial Intelligence in Learning on Student Self-Efficacy and Self-Monitoring. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 107, 68. https://ejer.com.tr/manuscript/index.php/journal/article/view/1438

Sun, H., Yuan, C., Qian, Q., He, S., & Luo, Q. (2022). Digital resilience among individuals in school education settings: a concept analysis based on a scoping review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 858515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.858515

Swiecki, Z., Khosravi, H., Chen, G., Martinez-Maldonado, R., Lodge, J. M., Milligan, S., … & Gašević, D. (2022). Assessment in the age of artificial intelligence. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100075

Tekyan, A & Yudkowsky, R. (2009). Assessment Portfolios. In: S.M. Downing & R. Yudkowsky (Eds.). Assessment in Health Professions Education (pp.287-303). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203880135

Van Tartwijk, J., & Driessen, E. W. (2009). Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE Guide no. 45. Medical teacher, 31(9), 790-801. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590903139201

Velander, J., Taiye, M. A., Otero, N., & Milrad, M. (2024). Artificial Intelligence in K-12 Education: Eliciting and reflecting on Swedish teachers’ understanding of AI and its implications for teaching & learning. Education and Information Technologies, 29(4), 4085-4105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11990-4

Walker, B., Holling, C.S., Carpenter, S.R., & Kinzig A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267673

Weber, M., Engert, M., Schaffer, N., Weking, J., & Krcmar, H. (2023). Organizational capabilities for AI implementation—coping with inscrutability and data dependency in AI. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(4), 1549-1569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-022-10297-y

Weller, M., & Anderson, T. (2013). Digital resilience in higher education. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 16(1), 53-66.

Williams, P. (2019). Does competency-based education with blockchain signal a new mission for universities? Journal of higher education policy and management, 41(1), 104-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1520491

Yang, S. J., Ogata, H., Matsui, T., & Chen, N. S. (2021). Human-centered artificial intelligence in education: Seeing the invisible through the visible. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100008

Yang, T. C. (2023). Application of artificial intelligence techniques in analysis and assessment of digital competence in university courses. Educational Technology & Society, 26(1), 232-243. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48707979

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education–where are the educators? International journal of educational technology in higher education, 16(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2024). A systematic review of ePortfolio use during the pandemic: Inspiration for post-COVID-19 practices. Open Praxis, 16(3), 429-444. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.16.3.656

Zhang, J., & Zhang, Z. (2024). AI in teacher education: Unlocking new dimensions in teaching support, inclusive learning, and digital literacy. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(4), 1871-1885. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12988

AUTHOR

Hugo Lotriet is a professor of Information Systems at the University of South Africa. His research interests include the sociotechnical and ethical aspects of Artificial Intelligence, and the implications of these for education, organisations and society.

Email: lotrihh@unisa.ac.za