32 Using ePortfolios to Build Healthier, Post-Pandemic Online Learning and Professional Development Programs

Meghan Velez, University of Central Florida

Janine Morris, Nova Southeastern University

Amy Cicchino, University of Central Florida

Kevin E. DePew, Old Dominion University

Rich Rice, Texas Tech University, USA

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic forced a rapid shift from traditional to online learning environments, exposing gaps in educator preparedness. While research has highlighted the potential of student-created ePortfolios to support motivation and flexibility during this period, less attention has been paid to the role of educator-created ePortfolios in fostering digital resilience. The current chapter presents a case study of seven educators participating in the Global Society of Online Literacy Educators’ (GSOLE) asynchronous literacy instruction certification program during 2020–2022. Drawing on interview data and ePortfolio analysis, we identify ways in which these digital spaces supported professional agency, reflection, and connection amid institutional pressures and widespread isolation. Findings suggest that ePortfolios served not only as cumulative projects for the certification program but also as dynamic tools for cultivating emotional, cognitive, and social competencies—key components of digital resilience. Participants reported enhanced pedagogical awareness, learner-centered assessment strategies, and a renewed sense of community and professional identity.

Keywords: Certification Program, Digital Resilience, Global Society for Online Literacy Instructors (GSOLE), Online Literacy Instruction (OLI), Professional Development, Professional Identity

INTRODUCTION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, educators worldwide faced a sudden upheaval of traditional teaching models, shifting rapidly to online environments with limited preparation and support. The disruption challenged pedagogical practices, strained professional identity, and challenged community networks. Resilience, the ability to adapt to, learn from, and recover in disruption, became essential. Digital resilience, specifically, involves more than just strengthening technical skills for students and teachers; it’s a dynamic process combining emotional, cognitive, and social competencies, whether that includes introducing a new learning management system, shifting from in-person to online learning modalities, staying current with evolving tools and emerging technologies, developing a flexible and proactive mindset, recovering from setbacks to move past feeling overwhelmed or disconnected, or learning through disruption to strengthen skills and strategies for the future (Ge, 2025; Liu & Zhang, 2025; Martins et al., 2025; Tonga & Kara, 2025). Building dynamic digital resilience must involve intentional pedagogical practices and professional development activities.

Existing research highlights the potential of ePortfolio pedagogies to support digital resilience in student learners. Zhang and Tur’s (2024) review of pandemic-era ePortfolio literature illustrates ways in which student-created ePortfolios provided a motivating and flexible learning experience during remote instruction. However, research is lacking on how educator-created ePortfolios might support digital resilience through connection, reflection, and growth, especially in times when institutions prioritize compliance over meaningful development. The current chapter serves to help address that gap by analyzing a case study of seven educators who developed professional ePortfolios during the 2020–2022 Global Society of Online Literacy Educators’ (GSOLE) asynchronous instructional certification program (https://gsole.org/certification).

Through interviews with participants and ePortfolio analysis, this chapter explores how educator-created ePortfolios supported digital resilience by enabling participants to document pedagogical growth, receive feedback, and stay connected during mandated isolation periods. More than static evaluation tools, these ePortfolios functioned as authentic, dynamic spaces for reasserting professional agency, encouraging resilient behaviors, and experimenting with learner-centered, metacognitive assessment practices.

Educators in this study have since transitioned back to face-to-face teaching or adapted to hybrid models, with increased understanding of ways in which ePortfolios can cultivate digital resilience. The study offers insight into how professional development rooted in reflection and connection can empower educators to endure digital disruption as well as evolve through it. ePortfolios, thus, counteracted isolation and modeled authentic assessment techniques that are learner-centered, metacognitive, and focused on growth and development (Mudau, 2022).

Specifically, the chapter demonstrates how professional development ePortfolios can promote engagement and support educators embracing digital resilience, specifically: (1) understanding when at risk, (2) knowing what to do to seek help, (3) learning from experiences, and (4) having appropriate support to recover (Manning, 2025).

LITERATURE REVIEW

While metaphors of resilience became popular in educational, economic, and environmental discourse before the pandemic, the disruption and trauma caused by COVID-19 resulted in increased interest in resilience as a concept, especially as educational leaders and policymakers considered how best to return students to a state of equilibrium or balance as quickly as possible without losing any more ground (Jimenez, 2025; UNESCO et al., 2021). However, as Flynn et al. (2012) note, resilience is often framed in educational contexts as “academic success understood and measured in traditional and conservative ways” (p. 5), ignoring the more complex relational, social, and transformational aspects of resilience. Our chapter draws on resilience frameworks from communication and rhetoric in addition to theories of digital resilience to reflect how ePortfolios fostered resilience in online educators during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Digital Resilience as Communicative, Community-Rooted Practice

Communication scholars have long emphasized resilience as an interactive process rooted in communicative practice. Patrice Buzzanell (2010) describes resilience as comprising five complex processes: crafting normalcy, affirming identity, developing and preserving communication networks, utilizing alternative logics, and balancing negative affect with productive action (p. 3). Buzzanell (2010) emphasizes that such resilience is rooted in community, which is something many educators lost during the pandemic’s isolating shift to emergency remote teaching. In response, some turned to online professional development to rebuild support systems and find purpose through reflective, digital practices. For participants in the certification, the ePortfolio became a space for showcasing competencies and enacting resilience through self-directed learning, peer engagement, and ongoing narrative construction.

Like Buzzanell (2010), Flynn et al. (2012) discuss resilience as a social and relational “process of rhetorically engaging with material circumstances and situational exigencies” (p. 7). For Flynn et al., resilience is neither fixed nor a static end goal; rather than focus on a return to equilibrium, their rhetorical approach to resilience envisions “an ongoing responsiveness, never complete nor predetermined” (p. 7). We see this ongoing responsiveness as particularly important considering how educators have continued to practice resilience strategies post-pandemic. When contextualized within online learning environments, resilience can become digitally mediated, especially shaped by an ability to sustain learning, build networks, and adapt communicative practices in response to technological and institutional exigencies.

ePortfolios and their Role in Building Resilience

Professional development networks help and support educators. ePortfolios when used in these contexts can be tools for assessment and reflection as well as catalysts for building professional learning communities and academic networks. Loescher (2021) writes ePortfolios can facilitate shared learning and trusted common spaces for educators to get help from peers. Zhang and Tur (2022) suggest collaborative ePortfolio practices can create supportive learning communities. Multiple scholars argue that ePortfolios promote collaboration and sustained engagement by enabling individuals to share teaching philosophies, instructional strategies, and feedback (Garrett et al., 2020; Tur & Urbina, 2022). Specifically, ePortfolios function as connective platforms where educators and students can narrate their growth, showcase competencies, and engage with broader disciplinary and institutional communities (Badenhorst & Xu, 2016).

These platforms can foster professional identity within larger dialogues around pedagogy, equity, and innovation (Buyarski et al., 2020). Furthermore, collaborative ePortfolio initiatives have been shown to increase educators’ sense of belonging and resilience, particularly during periods of institutional change or isolation (Batson et al., 2022). Thus, when embedded within reflective and interactive frameworks, ePortfolios link individual development to collective knowledge-building and peer support. Such resources allow teachers to articulate challenges, share experiences, and get guidance.

To stay resilient, we must first recognize signs of digital burnout and pedagogical fatigue. Research shows that many educators experienced increased stress and decreased well-being when moving online. Canani and Seymour (2021) found South African educators faced significant challenges in adapting to emergency remote teaching, and many struggled to use learning management systems. Hizam et al. (2021) noted educators’ digital competencies were often inadequate, and this led to difficulties in task performance and system usage. Such findings are repeated in scholarship (see Hilty et al., 2025; Lebedeva & Pasko, 2025; Yang et al., 2025), highlighting the need for self-awareness and institutional support to recognize when we are at risk of digital burnout. Yulin and Danso (2025) reason that focused training and institutional policies are needed to improve digital pedagogical preparation and navigate digital disruptions.

Collaborative features of ePortfolios, as highlighted by Zhang and Tur (2022), can be a way for educators to get feedback, share resources, and build support networks for recovery and growth. ePortfolios promote self-regulation, reflection, and evaluation, enabling educators to track their learning and pinpoint areas for growth (Zhang & Tur, 2024). The shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic showed us that teachers need digital resilience. Knowing when to ask for help, how to ask for help, learning from experiences, and having support to recover are key to building this digital resilience. ePortfolios and reflective practices can help educators navigate challenges, build their capacity, and continue to grow in the ever-changing education landscape (Wills & Rice, 2013).

METHODS

Data for this study comes from a larger IRB-approved effort to assess the efficacy of GSOLE’s Basic OLI Certification program, an eight-module, graduate-like certification designed to teach educators online literacy instruction (OLI) through the affordances of digital technologies. Learners create artifacts in each module (i.e., they choose from a list of possibilities), and the program culminates with an ePortfolio of select artifacts in which participants apply OLI theories to their local institution(s) and role(s). The capstone ePortfolio is evaluated pass/fail by a panel of reviewers, with failing submissions receiving an opportunity to use feedback to revise. The project enables participants to create both usable artifacts and a living archive of online literacy praxis, which they can share with administrative, peer, and/or hiring committee audiences, depending on their career and learning goals. All ePortfolios in this study passed either on the initial review or after one revision.

The seven (7) participants completed the certification and ePortfolio between 2020 and 2022. In addition to analyzing ePortfolios, the research team of certification administrators and instructors conducted two interviews with participants, one immediately following certification completion and one a year later. Participants worked either at four-year or two-year institutions and held a range of professional appointments. Four (4) had pre-pandemic experience teaching online. With the exception of Dave, all participants were female. Additional demographic information is provided in Table 1 below:

Table 1

Participant Demographics: all names presented are pseudonyms (created by Authors)

|

Participant |

Role |

|

Dave |

Full-time, non-tenure-track faculty at four-year university |

|

Farah |

Full-time K-12 and college bridge educator with tenure at a two-year college |

|

Erin |

Ph.D. student & writing center administrator (staff) member at private four-year university |

|

Amanda |

Professor Emerita, former writing program administrator |

|

Candace |

Full-time non-tenure-track faculty at a four-year university |

|

Brittany |

Part-time writing center staff at a two-year college |

|

Grace |

Full-time, tenure-track faculty and program administrator at a four-year university |

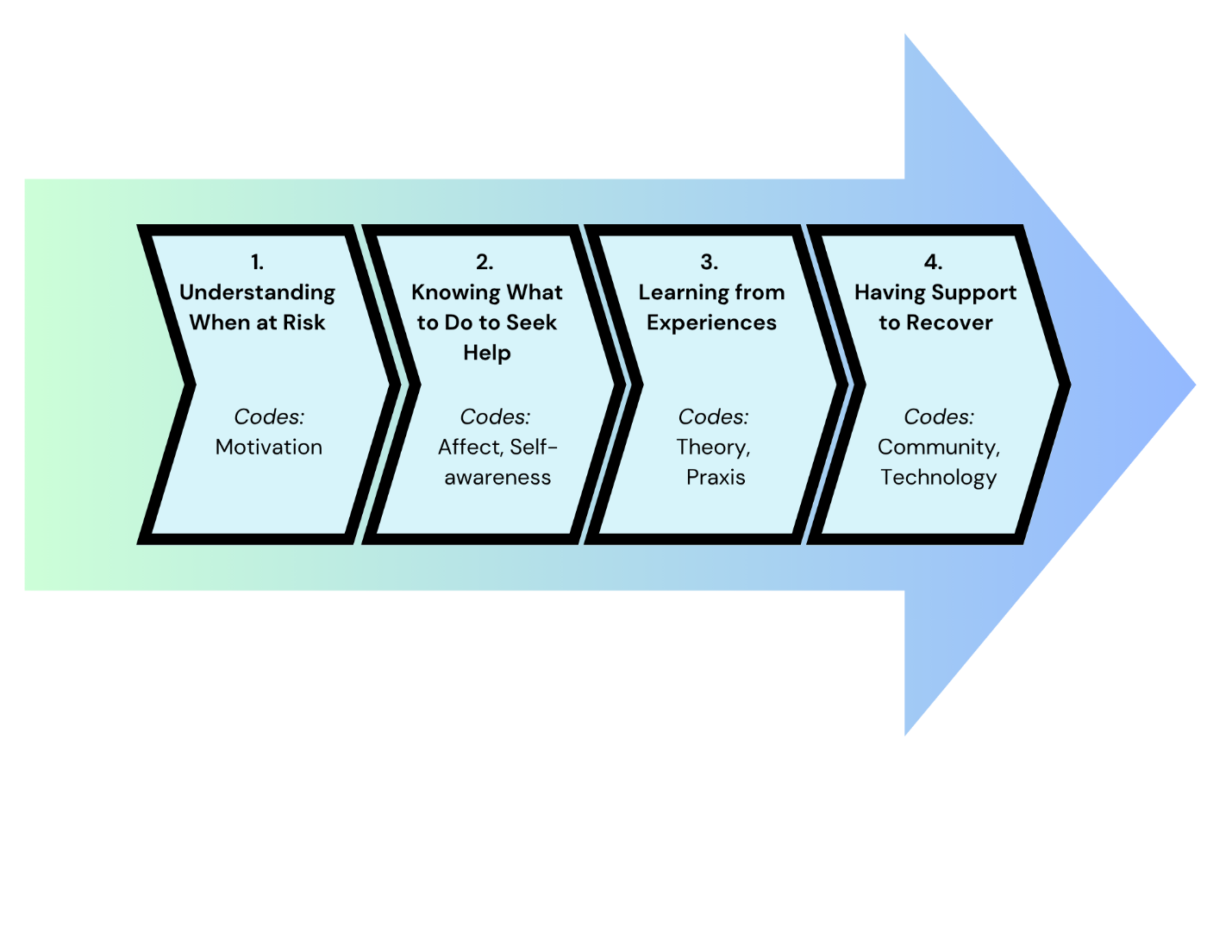

We posed the following research questions in this study. How did the certification generally and the ePortfolio specifically support digital resilience by helping participants (1) understand when they are at risk, (2) know what to do to seek help, (3) learn from experiences, and (4) have appropriate support to recover? As they coded interview transcripts and ePortfolios, researchers used grounded theory-informed, inductive methodological approaches (Glaser & Strauss, 1999), such as recursive questioning and discussion, axial coding, thick descriptions, and saturation. Additionally, researchers overlaid codes based upon our knowledge of the certification practices and objectives with Manning’s (2025) digital resilience framework (see Figure 1 below) to investigate the ways participants did or did not leverage the ePortfolio composing process, their time in the certification, and the affordances of the digital technologies to practice resilience. Researchers used ATLAS.ti to generate and test codes, coding interview transcripts and PDFs of participant ePortfolios, coding each t-unit length (i.e., 1 unit of thought), and defining the boundaries of each code by limiting analysis to no more than double-coding each t-unit.

FINDINGS

Codes that emerged from these data are aligned with the four stages of digital resilience development (Manning, 2025): (1) understanding when at risk (Motivation), (2) knowing what to do to seek help (Affect, Self-Awareness), (3) learning from experiences (Theory, Praxis), and (4) having appropriate support to recover (Community, Technology) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Coding schemes aligned with digital resilience development

1. Understanding When at Risk

The Digital Resilience framework begins with a responsive need to understand when individuals are at risk (Manning, 2025). Risk, in this context, is not abstract but emerges from specific conditions, experiences, and exigencies (Flynn et al., 2012). For participants, awareness of risk manifested in their motivations for enrolling in the certification and completing the ePortfolio. These risks were technical and logistical as well as deeply personal and professional, shaping how participants engaged with the program and ePortfolio process.

The program launched during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was a time when many educators faced heightened uncertainty and instability. Participants, therefore, identified risk as embedded in their teaching and learning experiences prior to and during their enrollment. For some, the pandemic marked an abrupt entry into online teaching, mostly without adequate preparation or support. Erin said, “I began teaching during the pandemic. So, in the fall of 2020, I was thrown into teaching after completing my M.A. And by thrown, I will say I did not have GTA experience or teaching experience prior to that.” Here, risk is tied to professional vulnerability and lacking experience, which the certification helped mitigate.

Similarly, when asked why she chose to enroll, Candace stated, “We were in the pandemic, of course, and I felt like my experiences teaching face-to-face weren’t translating into online.” Amanda, meanwhile, had a negative experience with online learning as a program administrator after several online modules she built struggled to scale across the needs of other online instructors. Her desire to complete the certification was to reassure her to “be a little better prepared in case somebody crashes.”

Participants viewed certification and ePortfolio as tools to manage professional precarity outside of pandemic circumstances as well. Erin explained how her ePortfolio would assist her in securing employment:

It’s such an expansive ePortfolio compared to some of the ones that I’ve seen, especially. I mean not to put myself up on any pedestal or toot my own horn, but like I’m obviously in a PhD program with other PhD students who don’t have ePortfolios and don’t have artifacts and don’t have teaching statements, or you know… I left this certification with not only a certification, but I have, like all of this stuff to showcase.

Similarly, Farah, a full-time faculty member, used her ePortfolio in tenure and promotion and planned to reuse it for doctoral applications: “I got tenure, and I used it for my appraisal process. It’s a part of my documentation that they send out to the district office for whenever I apply to jobs. I’m planning on using it for doctoral applications, so it will be used over and over again.” For both participants, professional status was understood as risky and professionally precarious.

Another motivational factor was the need to grow as an online educator or risk stagnation. Candace specifically contrasted this growth with lacking institutional recognition: “I don’t see [my administration] doing cartwheels in the hallway about [the certification]. But, I don’t often do professional development because my institution wants me to do it. I do professional development for me because I feel like there’s always something else to learn. And because I learn better when I’m working with other people; I seek out class-type things, where I can interact with other people.”

For Candace, the opportunity to engage with other like-minded educators was enough, even if her institution would not recognize her accomplishment. Dave was most excited to be “around senior colleagues for more than just one meeting at a time,” providing opportunities to “influence [his] teaching” and “stay active in the field.” These motivations reflect a proactive stance toward professional growth, where risk is first identified and then embraced as part of ongoing learning and social community engagement.

2. Knowing What to Do to Seek Help

After identifying risk, resilient individuals should know what to do to seek support (Manning, 2025). However, that can be difficult when having to manage what Flynn et al. (2012) describe as the complex relational, social, and transformational aspects of resilience. For many participants, acknowledging their own affective responses to daunting tasks, like online teaching or ePortfolio development, and practicing self-awareness was necessary to transform often negative affect into productive action (Buzzanell, 2010).

These affective dynamics were evident as participants constructed their ePortfolios. Erin, who already had an ePortfolio from her master’s program, said, “Even though I had like a website and I had navigation pages and I had a teaching philosophy kind of you know drafted out, it was still an overwhelming process.” Brittany, who had taught with ePortfolios previously, admitted,

I came up with all the portfolio junk. And then I think I got so tired of portfolios, you know 15 years ago, like please stop. I just never really saw one come together from what it was supposed to be. And then I had to make one — [at first] that was terrible. I was like, ‘Wait what? Payback for all those students I made make these horrible portfolios that were really not thoughtful.

These examples show how the ePortfolio process reactivated prior anxieties and uncertainties, making ePortfolio development emotionally and cognitively risky while encouraging participants to move forward and seek support.

To navigate challenges during certification, participants demonstrated “ongoing responsiveness”—a self-awareness of their online teaching context and a readiness to seek support when needed (Flynn et al., p. 7). By enrolling, participants recognized the need for support or assistance with online teaching. Dave saw the certification as “a way to learn from senior colleagues,” recognizing, “I want to be the best teacher that I can be, and definitely with the importance or the pervasiveness of online education, I see it as marketable.” Beyond learning from colleagues, he expanded on his work with doctoral students and recognition that he had “never taken an exclusively online-pedagogy-driven-course.” Such self-awareness of his identity as a lifelong learner helped Dave position himself as someone who would benefit from the certification.

ePortfolios became particularly important sites for participants to practice self-awareness. For those with existing ePortfolios, the certification gave them a chance to refine and build on existing work. Amanda found it helpful to recognize that her previous ePortfolio was outdated: “it helped me realize how outdated mine looked. I created it like eight years ago, and it helped me just rethink it when we started thinking about how to display information, so that was really useful.”

Still, the ePortfolio creation process was not without challenges. Two participants described difficulties they had conceptualizing a public-facing digital portfolio. Candace questioned,

Okay, how do I move that into a portfolio that’s now public facing? And now there’s ethical issues in putting out someone’s work, admittedly with my commentary on it, but it’s still at the base of somebody else’s and so how to do that? So I’m not sure I completely navigated all of that super well but those were some of my struggles, as I put it together.

Erin wondered if her struggles stemmed from imposter syndrome or lacking technical knowledge,

Understanding how each artifact was supposed to situate itself on the portfolio [was hard], I think. I don’t know. I don’t… sometimes I wonder if it’s… that like imposter syndrome, like is it me not understanding the instructions, or am I not technical enough to understand? Should I have some sort of ground knowledge, like baseline knowledge, to begin this or to work through it?

Dave likened the experience to a capstone, requiring significant time and reflection: “I wasn’t ready, you know, so […] understanding what’s expected of me and really spending time on this kind of capstone experience right whether it’s an oral exam or whether it’s a GSOLE learning experience I think […] is actually a really good thing.”

Beyond participant self-awareness as online teachers, the construction of ePortfolios encouraged participants to become more resilient instructors within their institutional communities. Farah stressed how creating her ePortfolio helped her with “modeling what this might look like if we were to enact it in our own classrooms.”

She explained that building her ePortfolio helped her modify student capstone projects. As a practitioner interested in theories of writing transfer, Farah reported that her engagement with the course “really helped me expand into digital literacy, transfer, and being able to again transfer knowledge across different platforms.” Her self-awareness of the transferability of her ePortfolio was something she was able to advocate for, and it aided in her ability to respond and scaffold portfolio thinking for her students.

3. Learning From Experiences

As participants became more self-aware and reflective about their pre-pandemic teaching practices, they also applied new knowledge in the form of theory and praxis. In particular, participants noted that the certification was more theory-driven than professional development for online teaching offered at their institutions, and the certification’s emphasis on equity and accessibility represented new ways of thinking about online teaching and learning. Theory provided a community they were not receiving from institutional support mechanisms. In turn, theories gave participants language through which to describe their teaching practices as praxis, and the ePortfolios offered a space for participants to 1) document praxis, and 2) reflect on the overall impact of this new knowledge.

A cornerstone of the certification included monthly reading annotation assignments, typically consisting of academic articles and book chapters, and participants were encouraged to support teaching practice with theory in their ePortfolio artifacts and reflections. In interviews, many highlighted the emphasis on theory as being a unique and positive feature of the certification; Amanda contrasted it with the “tips and tricks” mentality of other professional development she had encountered.

Participants were also afforded opportunities to connect prior scholarship interests to online literacy theories. Farah, who enrolled in the certification after completing a master’s degree and before starting a Ph.D. program, shared that she continued updating her ePortfolio after the program. She reflected,

I revised it to also include discussion on digital identity and how we formulate ourselves online, so I’ve really have taken it into heart, a lot of the things that we’ve learned. Especially while I guess maintaining the integrity of what my initial scholarship has been about, but now I feel like, again, I’m maintaining that integrity of what I’ve really always wanted to study but I’m expanding it into a wider sphere and having more opportunities to apply it in different atmospheres.

The integration of theory and the ability to articulate the role of that theory in a teaching ePortfolio was important to Farah’s overall growth as an online educator and to her ability to transform her knowledge and practices.

While many appreciated the theoretical knowledge gained from the program, there were tensions in participant perceptions of the balance between theory and practice. Perhaps because the pandemic necessitated a rapid and disruptive shift to emergency remote instruction, some felt overwhelmed by the day-to-day experience of teaching online and wanted more pragmatic “tips and tricks” to stem that anxiety. By contrast, the more theoretical approach did not always respond to that immediate affective need. When describing aspects of the certification that might have been improved, both Amanda and Dave expressed this need for balance.

Amanda noted, “we got an awful lot of theoretical viewpoints and overviews, it might have been nice to like maybe at the end of semester, just to have a module it was just like, How does this play out in practical things.” In response to the same interview question, Dave discussed the balance of theory and practice in his ePortfolio:

In my initial portfolio feedback, I focused a lot on theory and not enough on practice. And I don’t know that that was necessarily a consequence of the course per se, because, like I just told you, I developed a reading response and developed digital learning materials during the class. But I don’t know it’s kind of like a paradox, I think, to say this as a complaint, because you know I, we could have, like, made a bunch of different learning materials. But if I didn’t have that theoretical grounding, I don’t know that I would be as prepared to move into this fall semester.

It is clear from Dave’s response that knowledge gained from theory was ultimately more helpful than the creation of practical materials in contributing to his long-term resilience as an online educator.

Throughout the creation of artifacts and reflection on their ePortfolios, participants were encouraged to combine theory and practice by providing specific examples of assignments or activities that they developed during the certification. These moments of praxis highlight ways in which participants applied OLI theories to the teaching and learning happening within their institutional contexts. Dave reflected on how his understanding of accessibility and labor-based grading theories shaped his ePortfolio:

I have my HTML anchors [on the pages], but… a rationale for grading contracts and then even a rationale for why not to practice traditional grading. And then I have some of this information that I was sharing about the WPA outcomes kind of controlling the kind of labor that students produce.

His comments illustrate how OLI theories informed both the structure of his ePortfolio and his pedagogical choices—particularly how he presents content and engages students through labor-conscious design.

During many interviews, participants described how the certification gave them a growing understanding of what their students might experience. Brittany reflected on how the certification caused her to rethink not only her technology skills, but also how her new learning affected her earlier knowledge of TESOL and tutoring in a writing center. She explains how the course readings inspired her to create and user-test a scavenger hunt to help students learn foundational skills “in a different and engaging way.” Such activities were ultimately valued by her institution, as students were given prizes for participating in the scavenger hunt.

4. Having Appropriate Support to Recover

Participants repeatedly highlighted how the certification filled a gap left by institutional training, which often focused narrowly on technology rather than creating communities. Candace described on-campus support as “a lot of tech support things” like “Tech Tune Up seminar[s].” Erin said her institution’s professional development centered on “how to enhance your Canvas course” which often left her feeling like her “own support.” Farah said her institution didn’t have “a very even scale of practice…of how to use different pieces of technology.” These reflections suggest that while technical training was widely available, it often lacked the relational and pedagogical depth central to a community-centered approach to resilience.

In contrast, GSOLE offered a space where participants could engage with content and each other in a community of practice. Candace said while “already knew some [program members] from doing the OLI Community stuff” she was “introduce[d] to people [through course readings] and then I got to know you and other people in the program” including her faculty mentor. She went on to say, “and feeling like these aren’t just you know names on a document, but they’re actual people I know has helped me.” Erin was impressed when her instructor asked a question to the cohort: “‘Can someone help me learn?’ And I think we had talked about it in one of our meetings, one-on-one, so it really was kind of a learning from all levels.”

In addition to feeling connected, many have since taken on leadership roles in GSOLE or presented at the annual conference. Erin proudly declared “GSOLE…you guys are my people. I mean it’s where I feel the most connected.” Brittany, too, mentioned “in terms of GSOLE I feel as a community, I feel more connected. Like maybe on the periphery, but at least I feel like I have a space, I know where I could go […] I like that community.” Dave agreed, stating, “I do feel like I’m a part of a community that like accepts where I’m at and like wants to help me get better and like I want to be better.” Farah said, “I feel that when I get to talk to people about GSOLE…it really gives me a little bit of like an extra fire.”

The sense of belonging cultivated through the certification increased connectivity and community leadership with colleagues at their home institutions, too, a significant result given the isolation caused by COVID-19. Some facilitated online learning workshops. Farah became “the technology expert at [her] school,” teaching colleagues “different tools that people can use online, different ways that you can interact with documents, different ways, you can write online.” Dave mentioned he was warned by a mentor that “the more you will enhance your credibility on the topic, the more people are going to come to you looking for answers.”

He was asked to do professional development training, facilitating a brown bag seminar with his center for teaching and learning to “share about my GSOLE learning experience”; he added “I would definitely make the portfolio a piece of that presentation.” Erin said her boss often asks “about asynchronous work and trying to figure out asynchronous training in the Writing Center,” going on to explain, “he looks to me because I have all of this formal online instruction training.”

Finally, the ePortfolios themselves emerged as shareable artifacts of community and support. One emeritus participant took steps to archive the website for the next 30 years, even if she dies. Another included the link in her holiday cards to share with family. Dave said, “I do plan on showing it to students in class this fall as kind of like a bio sort of thing, because I think it is pretty comprehensive.” Participants also shared portfolios in professional contexts like “annual review documents” (Candace), appraisal and tenure processes (Farah), doctoral and job applications (Erin, Farah), and professional development training for colleagues at home institutions (Farah, Grace). In these examples, the ePortfolio becomes more than a static record of achievement, functioning as a dynamic medium for initiating conversations, sharing identity, and fostering a sense of belonging and support within and beyond institutional boundaries.

Although participants noted technological skills alone were insufficient for professional development, the certification and creation of ePortfolios did allow participants to gain technology skills that contributed to their growing resilience with online instruction. After completing the certification, many felt prepared to engage in “ongoing responsiveness” toward their “material circumstances and situational exigencies” (Flynn et al., p. 7), in part because their strengthened technological proficiency was paired with theoretical and pedagogical knowledge.

ePortfolios were essential as a space where participants could articulate growing development, reflect on theory, and connect the changes they saw in themselves with their teaching practices. Farah noted that the ePortfolio was an exercise in applying new knowledge about online learning, including concepts like universal design for accessibility and inclusion. Reflecting on her continued revisions one year after the program, Farah stated,

I changed some of the, like thematic, the design of it, so like trying to be more conscientious of, like, colors that I’m using. So I’ve been using some resources online that do, like, color matching and like, what are some good compatibility colors to avoid, you know, creating complications for people with vision impairments.

Importantly, Farah viewed creating an accessible ePortfolio as part of her broader goals as an educator, arguing, “It’s kind of connection as a whole, like you have to have the ability to like, see the learner you have to be, have the ability to represent the learner, again, trying to appease and create a safe environment for all learners.” While those completing the certification may have felt those changes as learners and educators, the ePortfolio became a space where individuals could document and keep track of those changes.

ePortfolios additionally encouraged participants to reflect on resources that would impact broader professional or teaching communities. Dave exemplified this intentionality by emphasizing how reflexive technology use shaped his pedagogy. After detailing how he and his students explored Zoom visualization tools, he described the “organizing principle” of his ePortfolio as: “how can I do what I do better using technology? […] As we have these learning outcomes, how can we teach to these learning outcomes better using technologies?” Dave’s teaching and ePortfolio both reflected a student-centered approach that emphasized helping students navigate and apply digital tools.

By modeling reflexive technology use—such as experimenting with Zoom visualization features—he encouraged students to explore how tools could enhance their learning. Likewise, in her ePortfolio and interviews, Farah used technology to highlight the ongoing nature of learning and professional development. Farah’s understanding of technology use and the creation of her ePortfolio inform her teaching and interactions with colleagues and students who need assistance.

n describing an ePortfolio assignment for her students, she reflected on stepping back and letting students lead their learning instead of jumping in and doing the work for students: she now gives students “more critical thinking and questions that are going to actually ignite more independence and agency for their own learning.” Her experience creating an ePortfolio shaped how she supports students—encouraging independence by asking guiding questions rather than stepping in, and helping them take ownership of their learning. In her ePortfolio, Farah writes,

Since I work at a high school-college partnership, we have resources from both the local school district and community college; however, the abundance of tools can be overwhelming…I focused on tools that would promote different composition techniques, including audio, visual, and written modals. In addition, the resources described in this chart also allow for synchronous and asynchronous learning through collaborative and remote opportunities to engage with the information.

Throughout their time in the certification, participants were able to learn to use different tools and technologies to foster connection and showcase their growth in the development of their ePortfolio.

CONCLUSION

This chapter problematizes resilience as “a simple return to balance, the ‘happy ending’ of a life story, and an individual triumph over circumstances” (Flynn et al., 2012, p. 6). The digital resilience illustrated by certification participants reflects the reality that many of us faced during the COVID-19 pandemic: we faced challenges, recognized threats, sought help, learned something, and applied what we learned to new or different contexts. Completing a sustained professional development certification while being called on to show resilience in so many other facets of their lives allowed participants to grow and adjust to institutional and personal constraints they faced. Ultimately, we found that resilience grows from community and that ePortfolios challenge traditional technology-first approaches to online professional development by putting people and their stories at the center.

Across ePortfolios and interviews, participants revealed motivations for enrolling and completing the certification and highlighted benefits of individualized approaches to ePortfolio creation. Material and situational constraints influenced why participants joined the certification, affected how they approached their ePortfolios, and continued to impact how they used their ePortfolios following certification. Findings highlight how approaches to resilience change person to person. Yet, our case reveals several lessons for educators wishing to incorporate ePortfolios for professional development, especially as tools encouraging digital resilience:

Understanding when at risk (motivation): Participants cited a range of logistical, technological, time-related, and personal motivations for enrolling in the certification and creating ePortfolios. For those overseeing professional development, it’s important to recognize these varied motivations early. Understanding why someone is pursuing training and allowing flexibility in ePortfolio creation can support participant persistence.

Knowing what to do to seek help (affect, self-awareness): While Flynn et al. (2012) and Manning (2025) highlight the social importance of resilience, our findings emphasize the affective dimensions that shape success. Participants faced emotional and technological challenges throughout the ePortfolio process—from conceptualization to revision. Access to appropriate technological and social support was essential for their development and influenced how they approached ePortfolio creation with their students. Self-awareness and reflection can help individuals better understand their learning and growth and apply these insights across teaching contexts.

Learning from experiences (theory, praxis): A key strength of GSOLE’s certification was its grounding in theoretically-informed technological practice. Integrating theory with hands-on experience posed both challenges and growth opportunities. It wasn’t enough to learn tools—participants needed space to reflect and connect ideas. As Flynn et al. (2012, p. 1) suggest, reinforcing the link between theory and practice can foster reflection, agency, and choice. The program’s flexibility in artifact creation allowed participants to express learning on their terms, enhancing authenticity and meaning.

Having appropriate support to recover (community, technology): Resilience, as Flynn et al. (2012) note, is inherently relational. While ePortfolios reflect individual growth, participants consistently pointed to the influence interactions with peers and instructors had on their development as technology users and educators. In contrast to many institutions’ focus on tools and technology tips, participant ePortfolios demonstrate how intentional technological choices impact professional learning and can impact teaching practices. For ePortfolio implementation, recognizing the importance of community and social connection is vital to participant success and sustained growth.

Resilience is ongoing, socially mediated, and deeply personal. Creating (virtual) opportunities for individuals to connect, reflect, and grow can result in sustained resilience that continues to evolve over time. As many participants attested, the community that was developed because of the certification has continued to influence participants—three even ran for GSOLE leadership positions, and one has since become an instructor in the certification program. Just as participants described during their interviews, what they took away from the certification affected them as teachers, colleagues, and practitioners. Connections fostered during certification have continued to sustain and affect participant professional identities and sense of self.

REFERENCES

Badenhorst, C. M., & Xu, X. (2016). Academic networking: Writing and publishing together. London Review of Education, 14(1), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.14.1.10

Batson, T., Chen, H. L., & Watson, C. E. (2022). Trends in ePortfolio practice: History, pedagogy, and innovations in assessment. Stylus.

Buyarski, C., Landis, C., McKinney, K., & Miller, R. (2020). Moving beyond compliance: ePortfolios as learning in practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 10(1), 1–12. https://theijep.com/pdf/IJEP361.pdf

Buzzanell, P. M. (2010). Resilience: Talking, resisting, and imagining new normalcies into being. Journal of Communication, 60, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01469.x

Canani, A., & Seymour, L. F. (2021). Describing emergency remote teaching using a learning management system: A South African COVID-19 study of resilience through ICT. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.09764

Flynn, E. A., Sotirin, P., & Brady, A. (Eds.). (2012). Feminist Rhetorical Resilience. Utah State University Press.

Garrett, N., Chen, H. L., & West, D. (2020). ePortfolio pedagogy: Creating communities of practice through online reflective practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 10(2), 131–141. https://theijep.com/pdf/IJEP371.pdf

Ge, D. (2025). Resilience and online learning emotional engagement among college students in the digital age: A perspective based on self-regulated learning theory. BMC Psychology, 13(326), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02631-1

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1999). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

Global Society of Online Literacy Educators (GSOLE). (2019). Certification and professional development courses. Global Society of Online Literacy Educators. https://gsole.org/certification

Hilty, D. M., Armstrong, C. M., Wright, S. D., Smout, S. A., Drude, K. P., Maheu, M. M., & Krupinski, E. A. (2025). Detection, evaluation, and best practices for technology-based fatigue to promote well-being. In D. M. Hilty, M. M. Maheu, & K. P. Drude (Eds.), Digital mental health: The future is now (pp. 89–113). Springer Nature Switzerland.

Hizam, S. M., Akter, H., Sentosa, I., & Ahmed, W. (2021). Digital competency of educators in the virtual learning environment: A structural equation modeling analysis. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.08927

Jimenez, K. (2025, Mar. 19). Schools closed and went remote to fight COVID-19. The impacts linger 5 years later. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2025/03/19/schools-closed-covid-19-pandemic-impacts-linger/77065748007

Lebedeva, N. A., & Pasko, O. A. (2025). Emotional burnout of lecturers as a manifestation of stress and methods of confronting them. In S. G. Taukeni & M. Mollaoğlu (Eds.) Integrating the Biopsychosocial model in education (pp. 261–290). IGI Global.

Liu, F., & Zhang, L. (2025). The role of digital resilient agility: How digital capability incompatibility affects knowledge cooperation performance in project network organizations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 29(1), 25–48.

Loescher, J. (2021). Taking the time to reflect and learn with ePortfolios. Digital promise. https://digitalpromise.org/2021/04/22/taking-the-time-to-reflect-and-learn-with-e-portfolios/

Manning, C. (2025). A framework for digital resilience: Supporting children through an enabling environment. UKCIS Digital Resilience Working Group. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/parenting4digitalfuture/2021/01/20/digital-resilience/

Martins, F., Cezarino, L. O., Challco, G. C., Liboni, L., Dermeval, D., Bittencourt, I., … & Bittencourt, I. I. (2025). The role of hybrid learning in achieving the sustainable development goals. Sustainable Development, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.3374

Mudau, P. K. (2022). Lecturers’ views on the functionality of e-portfolio as alternative assessment in an open distance e-learning. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 8(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijem.8.1.81

Tonga, M., & Kara, M. (2025). The rapid transition to online learning during the pandemic: Challenges and implications for digital transformation in higher education. In M. Tonga & M. Kara (Eds.), Virtual Technology Innovations in Education (pp. 245–268). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-6030-9.ch009

Tur, G., & Urbina, S. (2022). Teacher ePortfolios as professional learning and identity tools: A community of practice approach. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 38(5), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.7984

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), UNESCO Institute for Statistics, United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF Office of Research, the World Bank, & the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021, June). WHAT’S NEXT? Lessons on education recovery: Findings from a survey of ministries of education amid the COVID-19 pandemic. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379117

Wills, K. V., & Rice, R. (2013). ePortfolio performance support systems: Constructing, presenting, and assessing portfolios. The WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/eportfolios

Yang, D., Liu, J., Wang, H., Chen, P., Wang, C., & Metwally, A. H. S. (2025). Technostress among teachers: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Computers in Human Behavior, 168(108619), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2025.108619

Yulin, N., & Danso, S. D. (2025). Assessing pedagogical readiness for digital innovation: A mixed-methods study. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.15781

Zhang, P., & Tur, G. (2024). A systematic review of e-Portfolio use during the pandemic: Inspiration for post-COVID-19 practices. Open Praxis, 16(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.16.3.656

AUTHORS

Meghan Velez is Assistant Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Central Florida, where she teaches graduate and undergraduate courses in online, hybrid, and face-to-face modalities. Her teaching and research focus on digital writing technologies and literacies, writing center and writing across the curriculum/writing in the disciplines administration, and online writing pedagogy. Her most recent work can be found in the Journal of Business and Technical Communication, Thresholds in Education, and Communication Teacher.

Email: meghan.velez@ucf.edu

Janine Morris is an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication, Media, and the Arts at Nova Southeastern University, and a faculty coordinator of the NSU Writing and Communication Center. Her research interests span areas of writing studies including composition pedagogy and online writing instruction; media literacy and fake news; emotions, affect, and materiality; and writing center studies (with an emphasis on graduate student writing support). Her work has appeared in various writing studies and writing center journals. She is co-editor of Emotions and Affect in Writing Centers with Kelly Concannon.

Amy Cicchino is Director of the University Writing Center and an Associate Professor in the Department of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Central Florida. Her research takes up digitally enhanced teaching and composition, high-impact practices, and writing program administration and can be found in venues such as the Writing Center Journal, WPA: Writing Program Administration, and the International Journal of ePortfolio, among others. She also co-edited Better Practices: Exploring the Teaching of Writing in Online and Hybrid Spaces with Troy Hicks.

Kevin E. DePew is an Associate Professor of Writing Studies in the Department of English at Old Dominion University. His research and teaching interests–which are completely inseparable–occupy the axes of literacy, online writing instruction, linguistic justice, social justice pedagogies, and digital writing. Kevin and Beth Hewett co-edited Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction. His scholarship has appeared in venues such as Computers & Composition, Composition Studies, and Technical Communication Quarterly as well as edited collections like Better Practices, Emerging Pedagogies in the Networked Knowledge Society, Reinventing Identities in Second Language Writing and Digital Writing Research.

Rich Rice is Professor of Technical Communication and Rhetoric in the Department of English at Texas Tech University where he teaches and researches issues in composition and rhetoric, new media, ePortfolio pedagogy, online writing, intercultural communication, and service-learning. He directs the Center for Global Communication in TTU International Affairs Office and edits the Perspectives on Writing Series of The WAC Clearinghouse. Recent publications address topics like ePortfolio praxis, intercultural communication competence, ethical integration of AI in writing, and online writing instruction best practices. See https://richrice.com.