21 ePortfolios as an Overarching, High-Impact Practice for Teacher Education Programs

Dr. Norman Vaughan

Mount Royal University, Canada

ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the use of digital technologies in higher education. This chapter documents how ePortfolios can be used as an overarching high-impact practice (HIP) in a teacher education program. An action research framework was used to investigate the opportunities and challenges of a programmatic approach to ePortfolios. Teacher candidates (TCs) commented on how ePortfolios helped them integrate their coursework and field experiences throughout the program but indicated a major challenge was the decreased focus and emphasis from the 1st to final year of the program. The key recommendation was to create a guiding curriculum document for the B.Ed. program’s ePortfolio. This guiding document contains the framework, template, examples, and resources for the ePortfolio process.

Keywords: ePortfolio, high-impact practice, peer feedback

INTRODUCTION

During the Covid-19 pandemic, faculty and students in higher education pivoted to the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) due to lockdown restrictions that prevented face-to-face interaction (Krassadaki et al., 2022). Since the pandemic, the use of digital technologies has continued to increase, but often not in a systematic or coherent manner that benefits student learning. This chapter documents how digital or ePortfolios can be used strategically to serve as an overarching high-impact practice (HIP) for a degree program.

There continues to be a focus on the topic of student engagement in higher education in light of rising tuition costs and concerns about student success and retention rates. In 1998, the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) was developed as a “lens to probe the quality of the student learning experience at American colleges and universities” (NSSE 2007, p. 3). The NSSE defines student engagement as the amount of time and effort that students put into their classroom studies that lead to experiences and outcomes that constitute student success, and the ways the institution allocates resources and organizes learning opportunities and services to induce students to participate in and benefit from such activities. Originally, five clusters of effective educational practice were identified based on a meta-analysis of the literature related to student engagement in higher education. These benchmarks were (NSSE, 2007):

- Active and collaborative learning

- Student interactions with faculty members

- Level of academic challenge

- Enriching educational experiences

- Supportive campus environment

From the enriching educational experiences benchmark, Kuh (2008) identified ten high-impact practices (HIPs). These practices are defined as techniques and designs for teaching and learning that have proven to be beneficial for student engagement and successful learning among students from many backgrounds. The ten HIPs are:

- First-Year Seminars and Experiences

- Common Intellectual Experiences

- Learning Communities

- Writing-Intensive Courses

- Collaborative Assignments and Projects

- Undergraduate Research

- Diversity/Global Learning

- Service Learning, Community-Based Learning

- Internships

- Capstone Courses and Projects

After eight years of further research, Kuh (2016) announced the addition of ePortfolios as a HIP. There are now eleven HIPs, and this chapter documents how ePortfolios can act as a ‘spine’ or ‘backbone’ to support and integrate the other ten. The chapter investigates the following questions:

- How does an ePortfolio process allow students to connect their high-impact practice learning experiences throughout a degree program?

- What challenges do students encounter with ePortfolios for documenting their HIP experiences?

- Recommendations for improving the ePortfolio process as an overarching high-impact practice?

STUDY CONTEXT

Mount Royal University is a four-year undergraduate institution located in Calgary, Alberta, Canada (http://www.mtroyal.ca/). In the fall of 2011, the university launched a new Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) program, a four-year direct entry B.Ed. degree, with an emphasis on connecting theory with practice through the use of Kuh’s (2008) high-impact practices (http://www.mtroyal.ca/bed/). In the first year of the program, teacher candidates (TCs) have a year-long course that is focused on professional responsibilities. This course is connected to a weekly half-day school placement, where the TCs are able to put their learning into practice.

In the second year of the program, the TCs engage in year-long coursework focused on literacy development, classroom assessment, and individual child development. These courses are integrated with a weekly full-day school placement. For this placement, the TCs provide one-to-one or small group literacy support as well as various classroom activities and routines, including teaching lessons.

For the third year of the program, teacher candidates spend the fall gaining experience with interdisciplinary planning and learning by taking a program of studies courses in Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics (STEAM). For the months of September and October, they spend one day a week in a school placement that then extends to a 5-week practicum during the months of November and December. During the practicum, the TCs assume 25% of the teaching load, progressing to 50% for the final weeks of the practicum. For these practicums, a cohort approach is utilized, with at least four teacher candidates placed at the same school that allows for weekly in-school seminars.

Finally, in year four, the teacher candidates complete a 14-week practicum in the winter semester. This practicum focuses on professional responsibilities, planning for learning, facilitating learning, assessment, and inclusive environments. Teacher candidates are expected to be directly involved in all aspects of teaching, progressing from 50% and achieving 100% for at least five weeks of the practicum. The TCs connect practicum placement learning to a capstone course and an inclusive education course, which, along with a weekly seminar, take place in the practicum schools. These courses and the weekly seminar inform practicum learning and support the TCs in holistically thinking about their beginning teacher practice.

EPORTFOLIO PROCESS

A number of educational researchers have stated that assessment drives approaches to learning in higher education (Biggs, 1998; Hedberg & Corrent-Agostinho, 1999; Herman & Linn, 2013; Marton & Saljo, 1984; Ramsden, 2003; Thistlethwaite, 2006). Entwistle (2000) indicates that the design of the assessment activity and the associated feedback can influence the type of learning that takes place in a course or program. For example, standardized tests with minimal feedback can lead to memorization and a surface approach to learning, while an ePortfolio approach can potentially encourage dialogue, richer forms of feedback, and deeper modes of learning (Penny Light, 2016).

Faculty and teacher candidates involved in our Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) program have expressed increasing frustration with the Alberta Education assessment framework that relies heavily on standardized testing. They have observed that local school boards have recently begun to develop an ePortfolio process in order to foster and encourage deeper modes of learning (Foothills School Division, 2024). These online learning plans allow students to take ownership of the documentation and goal setting for their own growth and development throughout their kindergarten to grade 12 educational journeys.

In order to help our teacher candidates to be ‘experientially’ prepared for this type of learning environment, we require them to design, organize, facilitate, and direct their own online professional learning plan (ePortfolio) throughout the entire four years of our B.Ed. program. The purpose of this learning plan is for TCs to document and articulate professional growth and development related to the B.Ed. program competencies: planning, facilitation, assessment, environment, and professional roles and responsibilities (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Mount Royal University Bachelor of Education program’s five core teaching outcomes

These five categories were used to develop the learning outcomes and associated assessment activities for the high-impact practices (HIPs) in our B.Ed. program (http://tinyurl.com/bedcompetenices). The students maintain a Google Docs journal (http://tinyurl.com/bedjournal) to reflect on their learning experiences and develop an ePortfolio in Google Sites to document how the high-impact practices are helping them achieve the Alberta Interim Teaching Certificate KSAs (Alberta Education, 2028). This ePortfolio is the space for TCs to develop and communicate self-understanding and create learning goals and strategies that will allow them to be most successful in their future teaching practice (Johnsen, 2012). The key components of the ePortfolio are described in Table 1.

Table 1

Key components of the ePortfolio (created by Author)

|

Page

|

Description

|

|

Home |

Introduction and overview to personal teaching goals and aspirations |

|

Resume |

Documenting personal experience related to the K to 6 teaching profession |

|

Teaching evaluations |

Evaluations by mentor teachers from K to 6 school placement and practicum experiences |

|

Teaching philosophy |

Ongoing development of a personal teaching philosophy |

|

Journal |

Link to course and practicum journals in Google Docs |

|

Course reflections

|

A brief summary of the courses that students have taken at MRU. These include a link to the MRU course description and key “learning take-aways” from each course |

|

Teaching competency

|

Planning, facilitation, assessment, environment, professional roles & responsibilities with related artifacts, reflections, goals, and strategies |

METHODS OF INVESTIGATION

An action research approach in partnership with students and faculty was used to investigate the ability of ePortfolios to support high-impact practices in a degree program. There are various forms of action research, and the framework defined by Gilmore, Krantz, and Ramirez (1986) was utilized:

Action research… aims to contribute both to the practical concerns of people in an immediate problematic situation and to further the goals of social science simultaneously. Thus, there is a dual commitment in action research to study a system and concurrently to collaborate with members of the system in changing it in what is together regarded as a desirable direction. Accomplishing this twin goal requires the active collaboration of researcher and client, and thus it stresses the importance of co-learning as a primary aspect of the research process. (p. 161)

Stringer (2014) indicates that action research is also a reflective process of progressive problem solving led by individuals working with others in partnership or as a part of a ‘community of inquiry’ to improve the way they address issues and solve problems. This research approach should result in some practical outcome related to the lives or work of the participants, which in this case is the use of an ePortfolio process to help students connect and document their high-impact practice experiences in a degree program.

There have been concerns about the validity of this methodology, as it is often carried out by individuals who are interested parties in the research (i.e., faculty members) and thus potentially biased in the data gathering and analysis (Pine, 2008). The justification for action research counters this criticism by suggesting that it is impossible to access practice without involving the practitioner. Practice is action informed by values and aims, which are not fully accessible from the outside. Practitioners may not even be wholly aware of the meaning of their values until they try to embody them in their action (Kemmis, 2009).

We attempted to address the validity threat of this research design by investigating and integrating the perspectives of both students and faculty involved with the B.Ed. program’s professional learning plan (ePortfolio).

Data collection

A mixture of quantitative (i.e., student surveys) and qualitative data (i.e., faculty interviews) was collected. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with faculty members in the B.Ed. program, which were digitally recorded and transcribed (n=9). All students enrolled in our four-year B.Ed. program were invited to complete an online survey. There were 187 students who completed this survey from the 285 students registered in our program (response rate = 67%). The purpose of this survey was to collect data about how the students had connected their personal, classroom, and field-based learning experiences to document and demonstrate how they were achieving the Alberta Teaching Quality Standards. The SurveyMonkey (http://www.surveymonkey.net) application was used to administer this online survey.

The research study received institutional ethics approval, and the students and faculty members who participated in this study signed an informed consent form before the research process commenced. The consent form offered the participants confidentiality and the ability to withdraw from the study at any time.

Data analysis

Comments and recommendations from the faculty interviews and student surveys were added directly to a Google Document. This document was then reviewed using a constant comparative approach to identify patterns, themes, and categories of analysis related to the three research questions that “emerge out of the data rather than being imposed on them prior to data collection and analysis” (Patton, 1990, p. 390). In addition, descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, means, and standard deviations) were calculated for the online survey items using MS Excel.

FINDINGS

The findings and key themes are reported for each of the three research questions:

- How does an ePortfolio process allow students to connect their high-impact practice learning experiences throughout a degree program?

- What challenges are the students encountering with the ePortfolio for documenting their HIP experiences?

- Recommendations for improving the ePortfolio process as an overarching, high-impact practice?

1. Benefits of an ePortfolio as an overarching, high-impact practice

The faculty interview and student survey results indicate the teacher education candidates (TCs) perceive that the ePortfolio can be a useful overarching high-impact practice by:

- Having all my learning artifacts in one place to connect, critique, and reflect upon;

- Documenting professional growth;

- Journaling in each education course about high-impact practices; and

- Peer mentoring and collaboration.

In terms of having all of the learning artifacts in one place, a TC commented that “I think the professional learning plan really brings together all the components of the program, as well as weaving in our personal experiences” (TC survey participant 17). and “It has for sure helped me connect because I’ve had to think more about the things that I was noticing in the elementary school classrooms and having to connect it with the education course content” (TC survey participant 44).

With regard to documenting professional growth, one student stated that the learning plan process “forced me to see the connections and relevance between personal and professional life” (TC survey participant 23), and another student explained that “It allows me to display what I am learning while being able to go back and reflect on what I have learnt. As well, it allows me to build on my prior knowledge and to create a stronger professional learning plan” (TC survey participant 33).

Another student commented about the relationship between her course journals and the professional learning plan. “I have been able to include artifacts and pictures from my experiences in my learning plan that I have first documented in my field journals” (TC survey participant 6).

And, finally, a number of students emphasized the importance of the peer mentoring and collaboration high-impact practice that was involved in the construction of their professional learning plans: “I found that when I created my learning plan, I was able to input all my experiences into one space, and other people were able to see them and provide me with feedback; this made our class stay connected and become a community of learners” (TC survey participant 39) and “It has helped me to become more creative by seeing how the other students in my class think and learning from each of them” (TC survey participant 29).

2. Challenges of an ePortfolio as an overarching, high-impact practice

Findings obtained from the faculty interviews suggest that there is currently a tension with the ePortfolio process between being a surface versus a deep learning experience for the B.Ed. students. Faculty perceive that many TCs view the ePortfolio simply as a “checklist” or “set of hoops to jump through” in order to demonstrate their achievement of the Interim KSAs.

In addition, the teacher candidates identified a series of challenges, which have been categorized into the following three themes:

- Clarity of purpose;

- Time, and

- Digital technology support.

The survey results demonstrated that the teacher candidates are increasingly less clear about the purpose of the ePortfolio process as they progress through the program (Table 2).

Table 2

Clarity on the purpose of the ePortfolio process (created by Author)

|

Program Year

|

Percentage of TCs clear or very clear on the purpose of the ePortfolio

|

|

One |

78% |

|

Two |

70% |

|

Three |

58% |

|

Four |

46% |

The TCs indicate this downward trend is because the ePortfolio is not being applied to any of the core 3rd- and 4th-year education courses. “You only work on the portfolio in 1st or 2nd, and there is no opportunity to work on it in 3rd-year or 4th-year classes” (TC survey participant 132) and “It would have been more useful if the ePortfolio was implemented correctly in every course. Some professors emphasized its importance more than others, and therefore there were large gaps in between updates and various inconsistencies that we were required to fix on our own” (TC survey participant 87).

TCs from each year of the program also commented on the challenge of finding the time to work on their ePortfolios. In the first year, “It does take up a lot of time, but overall, I found it useful” (TC survey participant 14), while in the second year, “The least useful part of the ePortfolio process is that it requires time and a lot of thinking to plot information down on each page” (TC survey participant 53). These comments were echoed in the third year: “Unfortunately, time is always an issue. I felt as if I may not have had enough time to include insightful artifacts in my ePortfolio” (TC survey participant 114) and emphasized in the fourth year, “ePortfolios are mentioned, but we are never focused on them or given time to work on them in 4th year. They seem to always be an afterthought, and now I feel like I will be scrambling” (TC survey participant 156).

In addition, the TCs, especially in the 1st and 2nd years, emphasized the need for more digital technology support for the creation and maintenance of their ePortfolios. In the first year, “The least helpful part was having to figure out Google Sites on my own after only one workshop. I feel we didn’t spend enough time in creating it in class with our peers” (TC survey participant 27) and in the second year, “I am still not 100% comfortable with how Google Sites works. I think it would be really helpful to have a workshop to remind us of the things we learned in year one on how to create and maintain our ePortfolios” (TC survey participant 63).

3. Recommendations for improving the ePortfolio process as an over-arching, high impact practice

In terms of creating a deeper learning experience for the TCs, the faculty members recommended that the ePortfolio process should be revised in order to allow TCs to “tell their stories about how they are developing their professional teaching identities through the digital connection of their personal, classroom, and field-based learning experiences” (Faculty interview 3). In order to achieve this outcome, we have begun to examine the digital storytelling research literature (Barrett, 2006; Ehiyazaryan-White, 2012; Jenkins, M. & Lonsdale, 2007; Johnsen, 2012; Robin, 2005; Schank, 2012).

The teacher candidates who participated in this research study provided a number of ideas and suggestions for improving the overarching nature of the ePortfolio process. This “wish list” has been distilled into four key recommendation themes:

- Designated ePortfolio course for each semester of the B.Ed. program;

- Goal setting versus scrapbooking approach;

- Peer mentorship support; and

- Mentor teacher involvement.

One of the key challenges identified by the TCs was the lack of consistent focus and use of the ePortfolio throughout the entire B.Ed. program. In order to remedy this issue, they recommend that each semester a core education course be designated for the ePortfolio. This would involve creating an assignment for each of these courses that would provide TCs with a rationale and dedicated time to work on their ePortfolios along with assessment feedback to help direct their growth and development. Table 3 provides an overview of the proposed designated ePortfolio course framework.

Table 3

Designated ePortfolio education course framework for the B.Ed. program (created by Author)

|

Year

|

Fall Semester

|

Winter Semester

|

|

One |

EDUC 1231: The teacher: Professional dimensions I |

EDUC 1233: The teacher: Professional dimensions II |

|

Two |

EDUC 2371: Language Development and Literacy |

EDUC 2375: Effective assessment |

|

Three |

EDUC 3226: Understanding Current and Emerging Pedagogical Technologies

|

EDUC 3105: Program of Studies and Curriculum Instruction in Teaching Physical Education |

|

Four |

EDUC 4107: Program of studies and curriculum instruction in teaching social studies |

EDUC 4201: Integrating ideas, values, and praxis |

In many of the faculty interviews, concerns were expressed that the TCs approach the ePortfolio as a “checklist” or “set of hoops to jump through.” A superficial scrapbooking process rather than a deep and meaningful learning experience. Chen, Grocott, and Kehoe (2016) emphasize that we need to move our pedagogical and technological approaches from “one of checking off boxes to one of connecting the dots” (p. 1). Learning artifacts related to high-impact practices that are presented in the ePortfolio should be used to “trigger” growth and development goals and action plans as illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4

Teaching competency documentation and planning (created by Author)

|

Component

|

Description

|

|

Artifacts |

Representations of achievement of specific teaching competencies |

|

Reflections |

What I learned in the process of achieving this competency |

|

Goals

|

What future growth and development do I want to achieve for this competency |

|

Strategies |

What are my plans and strategies for achieving this future growth and development |

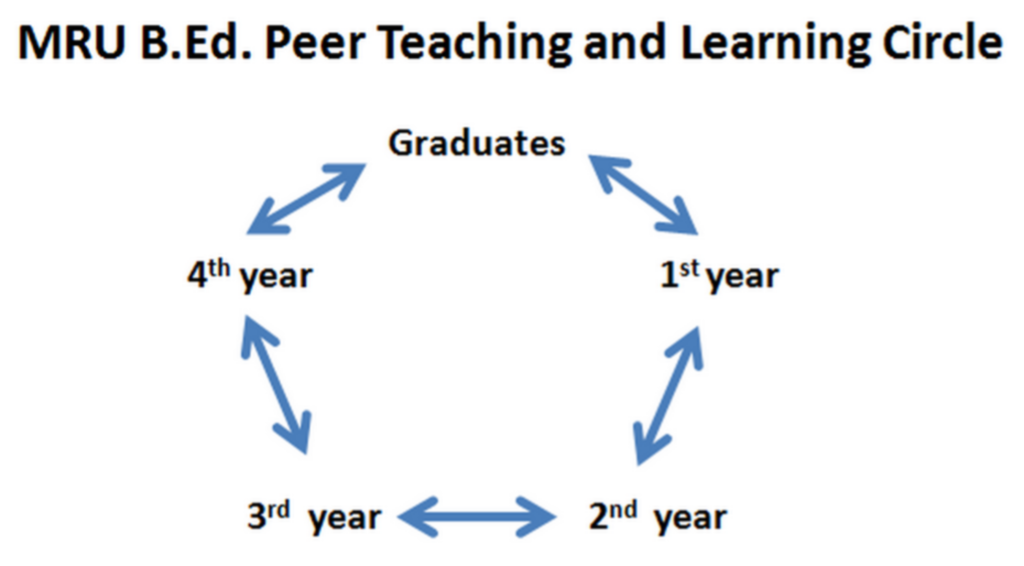

The TCs, especially in the 1st and 2nd years of the program, indicated that they would like to have more support for the ePortfolio process. Joubert (1842) is credited with coining the term “to teach is to learn twice,” and in a related study, Vaughan, Clampitt, and Park (2016) recommend the development of a peer mentoring circle for the B.Ed. program (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Bachelor of Education peer mentoring circle

In this circular approach, fourth-year TCs could receive peer mentor support for their ePortfolios from recent graduates, and in turn, the fourth-year TCs could provide volunteer support in the K to 12 classrooms of the recent graduates. Third-year TCs could be supported by fourth-year peer mentors in their first practicum experience. This would also help the four-year TCs reflect and prepare for their final practicum experiences. Second-year TCs could receive third-year peer mentor support in their assessment course, which in turn would also allow the third-year TCs to get feedback on the assessment activities that they plan to incorporate in their first practicum. Finally, the first-year TCs could receive second-year peer mentor support for the initial development of their ePortfolios and, in turn, could get feedback from the first-year TCs on their second-year ePortfolios.

The development of this peer mentoring circle would provide all TCs with “firsthand” mentoring experience to help them become effective teachers and learners. Friessen (2009) has developed a teaching effectiveness framework that emphasizes “teachers improve their practice in the company of their peers” (p.6), and an Alberta Education (2014) report advocates that an effective teacher “collaborates to enhance teaching and learning” (p.29).

Currently, conversations about the ePortfolio process are limited to the faculty members and TCs in the B.Ed. program, and as the African proverb suggests, “it takes a village to raise a child.” Several of the TCs, in the online survey, recommended that the mentor teachers for field placements and practicums should be more involved in these conversations. In the first year, the TCs recommend that mentor teachers should be made more aware of the B.Ed. teaching competency framework (planning, facilitation, assessment, environment, professional roles, and responsibilities) so that they can provide advice and guidance related to these key outcomes. In the second year, they suggest that this conversation should be broadened to include topics such as inquiry, digital technology integration, literacy acquisition, lesson planning, and assessment. And, finally, in the third and fourth years, they stress that there should be a much greater emphasis on conversations with mentor teachers about unit planning, diversity, and inclusive education.

NEXT STEPS

Based on discussions and recommendations from teacher candidates and faculty involved in this study, we have begun to develop a guiding curriculum document for our B.Ed. program’s ePortfolio. The guiding document contains the framework, template, examples, and resources for the ePortfolio process (http://tinyurl.com/bedplp).

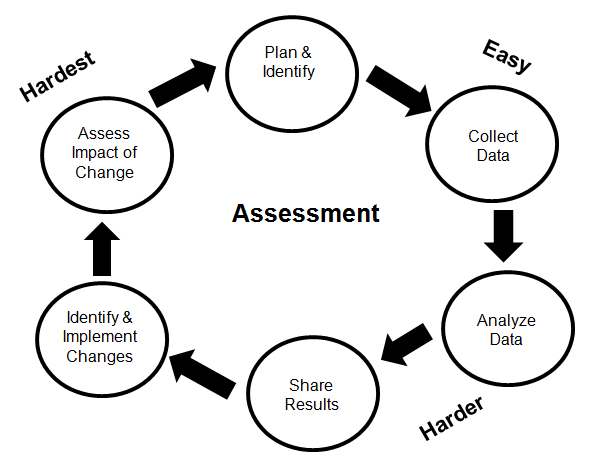

Our experience to date suggests that a student-faculty research partnership is particularly effective in the design and development of a new curricular approach, but that challenges can arise in the implementation phase due to faculty and student power dynamics in a university context when there is not mutual respect and trust between faculty and students. This aligns with Kuh and Associates’ (2015) assessment cycle, which demonstrates the increasing complexity of implementing change in higher education (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Assessment cycle

We speculate that a growing number of Bachelor of Education programs are using an ePortfolio process to document and assess teacher candidates’ growth and development. We hope that others are able to use and build upon the results of this student-faculty research partnership study in order to help teacher candidates effectively create their own professional identities by connecting their high-impact practice learning experiences in a digital format.

REFERENCES

Alberta Education. (2018). Teaching quality standard. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/4596e0e5-bcad-4e93-a1fb-dad8e2b800d6/resource/75e96af5-8fad-4807-b99a-f12e26d15d9f/download/edc-alberta-education-teaching-quality-standard-2018-01-17.pdf

Alberta Education. (2014). Task force for teaching excellence.http://open.alberta.ca/dataset/0c3c1074-b890-4db0-8424-d5c84676d710/resource/1315eb44-1f92-45fa-98fd-3f645183ac3f/download/GOAE-TaskForceforTeachingExcellence-WEB-updated.pdf

Barrett, H.C. (2006). Researching and evaluating digital storytelling as a deep learning tool. https://sites.google.com/view/electronicportfolios/home

Biggs, J. (1998). Assumptions underlying new approaches to assessment. In P. Stimson & P.

Morris (Eds.). Curriculum and assessment in Hong Kong: Two components, one system. (pp. 351-384). Hong Kong: Open University of Hong Kong Press.

Chen, H.L., Grocott, L.H., & Kehoe, A.L. (2016, March 21). Changing records of learning through innovations in pedagogy and technology. EDUCAUSE Review. http://er.educause.edu/articles/2016/3/changing-records-of-learning-through-innovations-in-pedagogy-and-technology

Ehiyazaryan-White, E. (2012). The dialogical potential of e-portfolios: Formative feedback and communities of learning within a personal learning environment. International Journal of ePortfolio, 2(2), 173-185. http://www.theijep.com/articleView.cfm?id=64

Entwistle, N. J. (2000). Approaches to studying and levels of understanding: The influences of teaching and assessment. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, XV (pp. 156–218). New York: Agathon Press.

Foothills School Division. (2024). Accessing my learning. https://www.foothillsschooldivision.ca/page/3128/accessing-my-learning

Friesen, S. (2009). Effective teaching practices—A framework. Toronto: Canadian Education Association. https://www.galileo.org/cea-2009-wdydist-teaching.pdf

Gilmore, T., Krantz, J., & Ramirez, R. (1986). Action-based modes of inquiry and the host-researcher relationship. Consultation: An International Journal, 5(3), 161.

Hedberg, J. & Corrent-Agostinho, S. (1999). Creating a Postgraduate Virtual Community: Assessment Drives Learning. In B. Collis & R. Oliver (Eds.), Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications (pp. 1093-1098). AACE: Chesapeake, VA. http://www.editlib.org/p/7040

Herman, J. & Linn, R. (2013). On the road to assessing deeper learning: The status of smarter balanced and PARCC assessment consortia. National Center for Research on Evaluations, Standards, & Student Testing: University of California at Los Angeles. http://www.hewlett.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/On_the_Road_to_Assessing_DL-The_Status_of_SBAC_and_PARCC_Assessment_Consortia_CRESST_Jan_2013.pdf

Jenkins, M., & Lonsdale, J. (2007). Evaluating the effectiveness of digital storytelling for student reflection. In R. Atkinson, C. McBeath, A.S. Swee Kit, & C. Cheers (Eds.), Providing choices for learners and learning ( pp. 440-444). Proceedings Ascilite, Singapore, 2007. http://www.ascilite.org/conferences/singapore07/procs/jenkins.pdf

Johnsen, H.L. (2012). Making learning visible with e-portfolios: Coupling the right pedagogy with the right technology, International Journal of ePortfolio, 2(2), 139-148. http://www.theijep.com/articleView.cfm?id=84

Joubert, J. (1842). Pensées. Par M. Paul De Raynal.

Kemmis, S. (2009). Action research as practice-based practice. Educational Action Research, 17(3), 463–474.

Krassadaki E., Tsafarakis S., Kapenis V., & Matsatsinis N. (2022). The use of ICT during lockdown in higher education and the effects on university instructors. Heliyon. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9649988/

Kuh, G.D. (2016). Ensuring That Undergraduate Inquiry Is a High-Quality, High-Impact Practice. CEL Conference on Excellent Practices in Mentoring Undergraduate Research. http://cel.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Kuh-Elon-slides-7-25-2016.pdf

Kuh, G.D. & Associates. (2015). Using evidence of student learning to improve higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Schuh, J. H., Whitt, E. J. & Associates (2005). Student success in college: Creating conditions that matter. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Marton, F. & Saljo, R. (1984) Approaches to learning. In F. Marton, D. Hounsell & N. Entwistle (eds.) The experience of learning. (pp. 165-188). Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

National Survey of Student Engagement (2007). Experiences that matter: Enhancing student learning and success – annual report 2007. Bloomington, IN: Center for Postsecondary Research.

Patton, M.Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Penny Light, T. (2016). Empowering learners with ePortfolios: Harnessing the “evidence of experience” for authentic records of achievement. The AAEEBL ePortfolio Review (AePR), 1(1), 5-11.

Pine, G. J. (2008). Teacher action research: Building knowledge democracies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to Teach in Higher Education (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Robin, B.R. (2005). The educational uses of digital storytelling. https://digitalstorytelling.coe.uh.edu/articles/Educ-Uses-DS.pdf

Schank, R.C. (2012). Every curriculum tells a story. https://aarongertler.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/sccwhitepaper.pdf

Stringer, E.T. (2014). Action research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Thistlethwaite, J. (2006). More thoughts on ‘assessment drives learning’. Medical Education, 40(11), 1149-1150.

Vaughan, N., Clampitt, K., & Park, N. (2016). To teach is to learn twice: The power of peer mentoring. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 4(2). https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/TLI/article/view/57442

AUTHOR

Norman Vaughan, Ph.D. is a Professor in the Department of Education at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He has co-authored the books Principles of Blended Learning: Shared Metacognition and Communities of Inquiry (2023), Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (2013), and Blended Learning in Higher Education (2008). In addition, he has published a series of articles on blended learning and teacher development. Dr. Vaughan is the Co-founder of the Blended Online Design Network (BOLD), a founding member of the Community of Inquiry Research Group, the Associate Editor of the International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning and he is on the Editorial Boards of numerous national and international journals. Additional information can be found on his personal website – https://sites.google.com/mtroyal.ca/normdvaughan/

Email: nvaughan@mtroyal.ca