14 Mignolo’s Influence: Beyond Epistemic Provincialism

Waishing Lam

Ahenakew, C., Andreotti, V., Cooper, G., & Hireme, H. (2014). Beyond epistemic provincialism: De- provincializing Indigenous resistance. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(3), 216-231. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011401000302

In this transnational collaboration, curriculum scholars Cash Ahenakew, Vanessa Andreotti, Garrick Cooper, and Hemi Hireme (2014) make a case to “de-provincialize Indigenous struggles;” i.e., to broaden the frames of reference that emphasize Indigenous ways of knowing and being in Indigenous education and resistance (p. 217). The authors assert that Indigenous wisdoms are often subjugated in favour of philosophies rooted in modernity and universalisms that favour Western/European thought and understandings that have and continue to oppress societies and perpetuate colonialism.

Grammatical Choices as Provincialism

The authors in this piece have drawn from work done in decolonial studies by scholars like Walter Mignolo (2007/2018), who makes the case for the need to “de-link” the “rhetoric of modernity and logic of coloniality.” Grammatical choices made in taking up Indigenous education often present the rhetoric of modernity as “objective, natural, and transparent” (Ahenakew et al., 2014, p. 217), essentially underpinning Western/European thought as the basis for all knowledge and understanding deemed “worth knowing.”

The deliberate choice by the authors to use the term “de-provincialize” has been used intentionally to make clear the connection to efforts to decolonize and de-universalize commonsensical understandings and universalisms of “how the world works.” Emphasis is placed toward the rhetoric of modernity’s “shine and shadow” that has imposed “intellectual restrictions that provincialize us in modern forms of existence by trapping and arresting resistance, and preventing us from experiencing (k)new knowledge” (Ahenakew et al., 2014, p. 219).

Andreotti (2014) describes this “shine and shadow” being with virtues like rugged individualism and progress while hiding the “unavoidable shadow of colonialism, imperialism, slavery, genocide, cultural repression, land theft, dispossession, destitution, extractivism, unfair trade, crippling debt, border controls, criminalisation of dissent, marginalisation, militarisation, environmental disaster and so on…” (p. 4).

Ahenakew et al. (2014) goes on to problematize that the rhetoric of modernity has become increasingly destructive from its former state of promoting elements of unfettered capitalism and industry, instead now characterized as “a dystopia… overtaking its utopic promise …[that] mobilizes new violent forms of racist othering, surveillance and control” (p. 219) revealing systemic issues that exist in existing institutional systems.

Implications for Curriculum

The practice of provincializing Western values “positions Indigenous knowledge as a means to an end” (Ahenakew et al., 2014, p. 220), often in the service of furthering the goals and mission of a conventional schooling system born out of the Industrial Revolution. Ahenakew et al. (2014) argue that seldom “Indigenous knowledge is represented as invaluable in and of itself” (p. 220). They go on to state that these Indigenous knowledges, if represented, are “often superficial, stereotypical and based on desires for redemption and re-centring of the Western subject” (p. 220) where Indigenous ways of knowing and being are dismissed as an implausible and unviable alternatives as tropes to reconciliation. These tropes are often evident in a plethora of course textbooks, approved course resources, and curriculum documents.

These concepts taken up by Ahenakew et al. (2014) assert that a priority in Indigenous education should be to “continue to (re)think the contradictions and paradoxes of survival within modern global capitalism,” and instead to create “generative spaces where alternative relationships between knowing and being can emerge and intervene in our lived realities, potentially creating new possibilities… new relationships, and new strategies of political and existential forms of resistance” (p. 218). Ahenakew et al. (2014) suggests an “epistemological delink” from the tensions of modernity and coloniality in favour of a “relink to ancient metaphysical principles of relationality” (p. 221) as a pathway to knowing and understanding another way to be a human being.

Implications for Educators

Teachers are implicated in this work as often, teachers may “provincial[ize] resistance within the landscape of modernity itself” (Ahenakew et al., 2014, p. 221). For instance, pedagogy that questions hegemonic structures of power and oppression through the integration of Indigenous ways of knowing and being used in the service of rationalizing or promoting existing systemic institutions is characterized by the authors as “selective, tokenistic and utilitarian” (p. 221). Instead, the authors argue that embracing kuia/kokum1 ethics: “…that emerges from being, rather than knowledge, thus ethical principles are lived, not talked about” (p. 225). The authors go onto state that kuia/kokum ethics aim to de-centre and de-universalize, and are “dependent on a very close relationship with the unknown and the mysteries and vicissitudes of life” (p. 226). In other words, the certainty and security that modernity offers by placing a high value in knowledge contradicts these ways of knowing and being. This leaves educators with the pedagogical conundrum of how to take up Indigenous ways of knowing and being beyond epistemic provincialism.

References

Ahenakew, C., Andreotti, V., Cooper, G., & Hireme, H. (2014). Beyond epistemic provincialism: De-provincializing Indigenous resistance. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(3), 216-231. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011401000302

Andreotti, V. (2014). Actionable curriculum theory: AAACS 2013 closing keynote. Journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Curriculum Studies, 10(1), 1-10. https://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/jaaacs/article/view/187728

Mignolo, W. D. (2007). Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality, and the grammar of de-coloniality. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 449-514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162647

Mignolo, W. D. (2018). The conceptual triad: Modernity/coloniality/decoloniality. In W. Mignolo, & C. E. Walsh (Eds.), On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics praxis (pp. 135-152). Duke University Press.

1 The Maori and Cree words for “grandmother” respectively, as noted in Ahenakew et al. (2014)

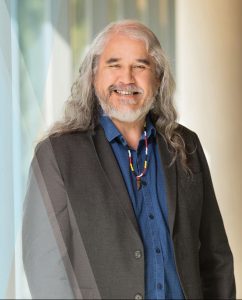

Media Attributions

- Dr.-Cash-Ahenakew-Spotlight-Image-scaled-1 © University of British Columbia

- Dr.-Vanessa-Andreotti-Spotlight-Image-scaled-1 © University of British Columbia

- Garrick-Cooper-low © University of Canterbury