Substance Abuse: Causes and Consequences

Addiction is often associated with substance abuse, yet many activities and behaviours can lead to an addiction. According to Tyler (2018, para. 1), “an addiction is a chronic dysfunction of the brain system that involves reward, motivation, and memory. It’s about the way your body craves a substance or behaviour, especially if it causes a compulsive or obsessive pursuit of ‘reward’ and lack of concern over consequences.” This definition can include many behaviours and activities such as gambling, shopping, working, eating, sex, technology, power, and stress. The important defining feature of addiction is the impact the activity has on the brain, making the behaviour very difficult to stop.

Defining addiction is important, as according to Halsey and Boodhai (2022, chapter 1.2, para. 4), the word addiction is loosely used to describe positive and negative behaviours, yet, “the stigma of the word addiction, however, seems to relate only to substances and behaviours that society deems inappropriate, dangerous, or unhealthy.” We have established the stigmatization of the terms mental health and mental illness; the same occurs with addiction.

Some addictions are deemed to be good, and some bad. Can you think of any examples? In North America, people addicted to work, known as workaholics, are labelled as productive go-getters, and it is seen as a positive personality trait. In contrast, individuals with substance abuse disorder are seen as unable to control themselves, weak, and unstable. Florin and Trytek (n.d., chapter 1) explored the history of beliefs around addiction and recovery, stating,

Today we recognize addiction as a chronic disease that changes both brain structure and function. Just as cardiovascular disease damages the heart and diabetes impairs the pancreas, addiction hijacks the brain. Recovery from addiction involves willpower, certainly, but it is not enough to “just say no” — as the 1980s slogan suggested. Instead, people typically use multiple strategies — including psychotherapy, medication, and self-care — as they try to break the grip of an addiction.

Research on the connection between addiction and the structure of the brain, specifically the flooding of the brain’s reward system with dopamine, is a big step towards understanding addiction, creating paths to healing and recovery that are effective, and reducing stigma around addictions.

Gabor Maté is a leading advocate linking addictions to trauma and adverse childhood experiences. Mindhealth360 (2018, para. 3) outlined Dr. Maté’s definition of addiction as

Firstly, craving the addictive substance or behaviour; secondly, engaging in the addictive substance or behaviour in order to experience pleasure or temporary relief from some kind of pain; and finally, the inability to give the substance or behaviour up. Addiction is an attempt to solve a problem. It is the symptom of a deeper malaise, in most cases, trauma. The most important question is not “why the addiction” but “why the pain?” In order to heal addiction, we must look at the underlying trauma. ALL addiction has its roots in some kind of trauma, but not all trauma leads to addiction.

All addictions are included in this definition; what makes the behaviour an addiction is the impact it has on one’s life. This general overview of addictions highlights the various behaviours that can manifest into an addiction. We will now look more closely at substance abuse disorder as one form of addiction that is highly stigmatized in society.

Substance abuse disorder is classified as a mental health condition under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders 5 (DSM-5). The DSM-5 is a “reference book on mental health and brain-related conditions and disorders written by the American Psychiatric Association” (Cleveland Clinic, n.d.).

Although there has been some criticism in labelling it as a disorder, there are some benefits to seeing addiction as a disease. As Florin and Trytek (n.d., chapter 1) stated,

some people are uncomfortable with the disease concept of addiction because they believe it removes responsibility from the using person. However, addictions specialists use the disease concept to remove the burden and guilt associated with the consequences of addictive use, while empowering the individual to take healthy steps toward recovery.

According to CAMH (n.d., para. 4), one model to aid in understanding addiction is the three Cs model. The three Cs are craving/compulsion to use, loss of control of amount or frequency of use, and continuing to use despite consequences. Florin and Trytek (n.d.) explored this model and provided a few examples of the three Cs, as seen below.

Information

Compulsion: A woman experiences intense urges to use cocaine while at work, and leaves her desk to get high in the bathroom.

Loss of Control: A college student intends to have one drink with a friend before going back to his room to study. He ends up having eight drinks throughout the night, and stays until the bar closes.

Consequences: A woman has been arrested and convicted three times for driving under the influence, yet she continues to drink and drive while denying that she has a problem.

(Florin & Trytek, n.d.)

Understanding the complexity of substance abuse disorder is important when working as a CSW, as many complex factors contribute to people’s struggle with addiction. Addiction, in particular substance abuse, has historically been viewed as an individual problem, one which can be overcome through willpower. Florin and Trytek (n.d.) outlined different theories to understand substance abuse disorder and concluded that the public health theory is the most complete. “The public health model takes various factors into consideration when identifying the causes of addiction. These factors are broken into three categories: the agent (the drug), the host (the individual), and the environment (those factors outside of the individual)” (chapter 2). Along with understanding the risk factors that lead to addiction, it is also important to consider protective factors that help to shield one from developing an addiction, or support one when in the steps to recovery.

Protective factors can be external or internal, and, “having one or more protective factors is not a guarantee that an addiction will not develop” (Florin & Trytek, n.d., chapter 2). The chart below was created based on a list of factors provided by Florin and Trytek:

Another chart by Public Safety Canada (2022, as cited in Halsey & Boodhai, para. 6) showed similar risk and protective factors, but categorizes them according to social influences. Both charts demonstrate the factors indicated in the public health model with an emphasis on external or community indicators. Another factor of influence may be the portrayal of substance use by media.

| Categories/Domains | Risk Factors | Protective Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Community |

|

|

| School |

|

|

| Family |

|

|

| Peer/Individual |

|

|

Activity

Questions for reflection:

- What role does the media play in influencing youth about using substances such as tobacco, drugs, and alcohol?

- Can you think of any examples where substance use is promoted in advertising or media, such as movies, TV, radio, and social media?

- What impact does culture have on substance use? Can you think of any gender differences in the encouragement or discouragement of substance use?

Now that we have a baseline for viewing substance abuse disorder as a complex problem that is multilayered in social, biological, psychological, and environmental factors, in addition to a basic understanding of how it impacts the brain’s reward system, we can look at some of the paths to intervention. One question posed by Halsey and Boodhai (2022, chapter 1.7) is, “Substance abuse and dependency is stigmatized, yet alcohol use is often culturally accepted. Why is that?” Substance abuse is often glamorized, yet individuals who experience addiction and substance abuse disorder experience stigmatization, social exclusion, and judgment, leading to deep feelings of shame and loss of self-esteem. This leads to difficulty in reaching out for help when one is struggling. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA),

In Canada, it is estimated that approximately 21% of the population (about 6 million people) will meet the criteria for addiction in their lifetime. Alcohol was the most common substance for which people met the criteria for addiction at 18%. Canada has one of the highest rates of cannabis use in the world, with more than 40 per cent of Canadians having used cannabis in their lifetime and about 10 per cent having used it in the past year (n.d., para. 5).

Canada is in the midst of a very concerning opioid crisis, which has impacted many families across the country. The opioid crisis is very complex, and while it won’t be discussed in detail here, as a CSW it is very important to be informed on what this crisis is, how it emerged, and what solutions are being used to combat this highly stigmatized, highly lethal drug-use crisis. There are many proposed solutions to support individuals struggling with an addiction or substance abuse disorder. Some of these will be discussed below.

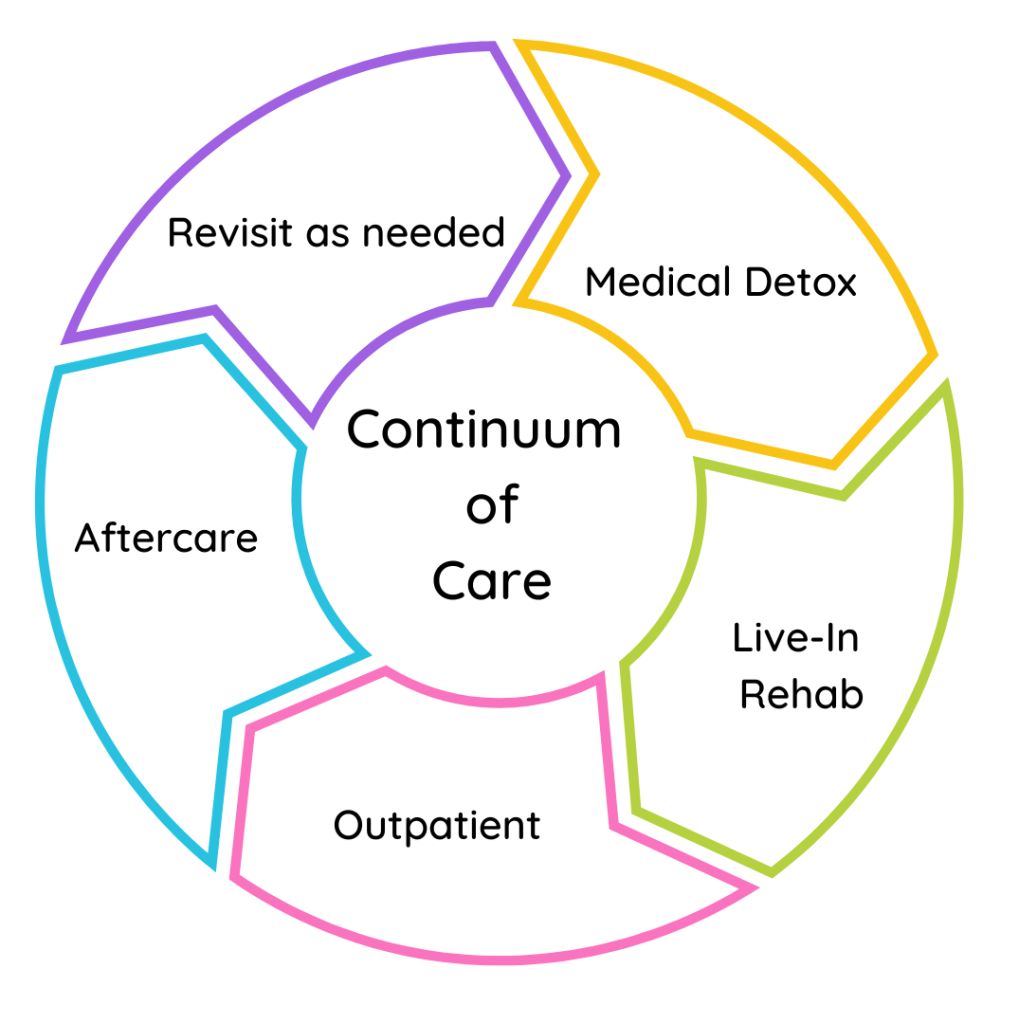

There are many paths to recovery depending on individual preference. Bearman and Schwan (2022) outlined the continuum of care, therapy, and support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous in Figure 6, below.

Medical detox is a very common approach to recovery, and is often court mandated. There are also many traditional paths to recovery that are culturally appropriate for Indigenous people that are more holistic, based on Indigenous knowledge and teachings, and acknowledge the impact of intergenerational trauma due to colonization and residential schools. Poundmaker’s Lodge, the first Indigenous treatment centre, was opened near Edmonton in 1973, and has

been a leader in the provincial, national and global addiction treatment community. Poundmaker’s Lodge accepts all peoples from all walks of life. Through concepts based in the cultural and spiritual beliefs of traditional First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples in combination with 12-Step, abstinence based recovery, Poundmaker’s Lodge also offers opioid treatment and an Indigenous wholistic treatment experience that focuses on the root causes of addiction and empowers people in their recovery from addiction (Poundmaker’s Lodge, n.d.).

As a community support worker, your job will involve being informed on the causes and consequences of addiction, the impact it has on clients, their families, and their social networks, be able to refer clients to appropriate resources, and provide support if a client discloses they are struggling with addictions or substance abuse disorder. Addiction is a common experience and goes beyond the individual impact, to that of the family and community.

References

Bearman, A., & Schwan, A. (2022). Psychology of addiction. PALNI Press. https://pressbooks.palni.org/psychologyofaddiction/

Canadian Mental Health Association. (n.d.). Substance use and addiction. https://ontario.cmha.ca/addiction-and-substance-use-and-addiction/

CAMH. (n.d.). Addiction. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/addiction

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). DSM-5. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/24291-diagnostic-and-statistical-manual-dsm-5

Florin, J., & Trytek, J. (n.d.). Foundations of addictions studies. College of DuPage. https://cod.pressbooks.pub/addiction/

Halsey, D., & Boodhai, S. (2022). Fundamentals of addiction – Trauma informed, solution focused counselling & case management. Affordable Course Transformation: The Pennsylvania State University. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/centennialfundamentalsofaddictiontraumainformedmotivationalinterviewingcasemanagement/

MindHealth360. (2018, December 5). Dr. Gabor Maté: Understanding addictive behaviour. https://www.mindhealth360.com/dr-gabor-mate-on-addiction/

Poundmaker’s Lodge. (n.d.). Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Centres: A place for healing, wellness and spirituality. https://poundmakerslodge.ca/

Tyler, M. (2018, May 25). What is addiction? Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/addiction

Image Credit

Figure 6: Treatment continuum by Andrea Bearman and Adelle Schwan for Trine University, CC BY 4.0.

To require someone or something else in order to function properly. Lack of self-reliance.

The passing down of trauma from one generation to another, which has a negative psychological impact. Research suggests that trauma can be passed down genetically.